Purchase Hungry Ghosts

(1:06) Publishing the novel

(4:07) Childhood reads

(12:47) Kevin's approach to writing

(18:41) Modern reading habits

(32:43) A book which changed his life

(39:49) Hungry Ghosts

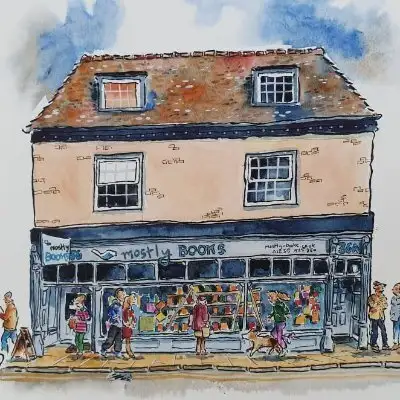

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a weekly podcast by the independent award-winning bookshop, Mostly Books. Nestled in the Oxfordshire town of Abingdon-on-Thames, Mostly Books has been spreading the joy of reading for fifteen years. Whether it’s a book, gift, or card you need the Mostly Books team is always on hand to help. Visit our website.

Meet the host:

Jack Wrighton is a bookseller and social media manager at Mostly Books. His hobbies include photography and buying books at a quicker rate than he can read them.

Connect with Jack on Instagram

Hungry Ghosts is published in the UK by Bloomsbury

Books mentioned in this episode include:

The Hobbit by J.R.R Tolkien - ISBN: 9780261103344

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D Salinger - ISBN: 9780241950432

Chernobyl Prayer: Voices from Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich - ISBN: 9780241270530

The Sound of the Mountain by Yasunari Kawabata - ISBN: 9780141192628

Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf - ISBN: 9781447299370

The Road by Cormac McCarthy - ISBN: 2928377128418

Creators and Guests

What is Mostly Books Meets...?

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a podcast by the independent bookshop, Mostly Books. Booksellers from an award-winning indie bookshop chatting books and how they have shaped people's lives, with a whole bunch of people from the world of publishing - authors, poets, journalists and many more. Join us for the journey.

Mostly Books Meets… Kevin Jared Hossein

Jack Wrighton - 0:05

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, the weekly podcast for the incurably bookish. We will be talking to authors and creatives from across the world of publishing and discussing the books they have loved. Looking for a recommendation? Then look no further. Head to your favourite cosy spot and let us pick out your next favourite book. On the podcast this week we welcome author Kevin Jared Hossein. His latest book Hungry Ghosts was published to great acclaim on the 16th of February. Set in rural 1940s Trinidad, Hungry Ghosts follows two households, the wealthy Changoors and the impoverished Sharups. It is a novel about family, caste, religion and violence. The late Hilary Mantel said of Hungry Ghosts that energy and inventiveness distinguish every page and Claire Orphrey in her review for the Times said that this Trinidadian Gothic deserves to be a Booker Prize contender. Kevin, welcome to Mostly Books Meets.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 1:05

Thank you for having me.

Jack Wrighton - 1:06

Our absolute pleasure. Now I know this isn't your first book and you've had stories published in various different publications, but it's very interesting sort of approaching this book when we first looked to have this book on our podcast. You know, there's a lot of great quotes for the cover from different authors. For you as an established author, approaching the the publication of any book, is there mixed feelings, is there nerves, or does it sort of now seem kind of second nature? What's it like from your side of things?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 1:35

There's many, many feelings. So I've published mainly in my region, the Caribbean region, not really outside of the Caribbean region. So we have a small but dedicated system and families, you know, so seeing it release widely at first and still is a bit pretty frightening because you wonder how the wider world would take, you know, the type of story and literature, even though I've had success in the Commonwealth short story prize and so on. There's a bit of second nature that comes to it that when you do publish a book, in a sense it doesn't belong to you anymore because you can't really go back and change anything. First of all, you can't hear the feedback criticisms, but you can't really do anything. So, and then you hear people's takes on it and you know, you kind of take that in and you realise that people form new and original ideas based on their work. So there's always the idea that you put this story out there and I mean there's a authorial sense to it but there's also as I said it doesn't truly belong to you anymore.

Jack Wrighton - 2:54

Does that ever get frustrating? I don't know, I can imagine you've spent obviously a long time writing this novel. Do you ever see one of the readers can take a novel down so many different roads? Do you ever feel frustrated with that? Or have you sort of resigned yourself to that aspect of storytelling?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 3:13

I have a habit of avoiding reviews when it comes out. Usually what happens is my agent kind of sums up I guess the good ones and sends them and there's cases where the book may have been read hastily or some parts may have been read insensitively. So there's those things as well. But, yeah, so in the sense of it, as I said, there's an initial pan of freight associated with it. But eventually you come to realise it is an entity of its own. I am really, really happy that Hungry Ghost, this particular book, is being released widely because it is specifically a very Trinidadian book, but it has universal themes. I think many people can relate to.

Jack Wrighton - 4:07

Yes, absolutely and we'll talk a bit more about Hungry Ghosts later on. But one of the things we like to do, we're a small bookshop in a small town in Oxfordshire, and we're sort of passionate about book selling. So one thing we'd like to do is sort of ask our guests to become, you know, booksellers kind of for the day and the first book we'd sort of like you to recommend or to talk about is a book from childhood or a children's book that you connected to either when you were younger or it can even be the one that you've read more recently, if I sort of approached you and said "oh could you recommend me a book linked to childhood" what would you be putting off the shelf?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 4:45

Right so funny little stories that when I was young my library was very limited so I did have a lot of non-fiction involving plants, animals, cultures that you know they were child-craft picture books, but you know, they were substantial still and I read those over and over. But when it came to fiction, one of my first memories is that there used to be this, this floating library, this boat, there used to dock in Trinidad's capital, Port of Spain, and they would sell books for cheap and they would go from island to island and sometimes to Venezuela, and my dad bought a workbook that was actually excerpts of novels. This would have been like White Fang from Jack London, The Hobbit by Tolkien and many others. But when I was little, I thought those were short stories because you have like 10 questions. You know, but one of the ones that struck me the most was the chapter that they had on The Hobbit, which was Riddles in the Dark. That was the one where, you know, you have Smeagol and Bilbo and I thought that was a short story for the longest time, you know, then I realised that it was a book. So then we got the book and I wasn't really interested in like some of the other books that might've been given to me as a youth. Like, I wasn't really interested in Robin Hood and Oliver Twist, but The Hobbit, it was something truly fantastical and not overcomplicated. You can read it for leisure. So I would say that's a good one to start off with with my childhood.

Jack Wrighton - 6:34

That's why it sounds quite a good, you know, we get in the shop regularly sort of abridged versions of kind of, you know, some of the classics for kind of younger readers, but the the sort of book of kind of samples of different stories sounds quite a nice way of, you know, being introduced because of course, particularly when you're a young reader, it can be quite daunting picking up a full story because if you start it and you don't like it, I certainly when I was younger always felt that I had to finish a book and these days I'm not so strict with myself, but that kind of sampling is a nice way of being introduced to it and not feeling the pressure of having to at least start with a whole book.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 7:14

They felt like demos for books.

Jack Wrighton - 7:19

Would you describe yourself as, you know, some children can be sort of voracious readers, whereas myself actually growing up I wasn't much of a reader as a kid, I struggled with reading. Were you a really big reader or just sort of, you know, give or take?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 7:32

Up until I was about 13 or 14 years old I really wasn't a big reader in a traditional sense, But what I did like was video games that involved a lot of reading. So a lot of role playing games with storyline might be 30-40 hours long and filled with dialogue and descriptions. I was really, really hooked on those and how I actually started writing was doing fan fiction, probably when I was like 13 years old. As I said, like, I was really struck by fantasy settings as well, you know, The Hobbit, whatever resonates with me. So I discovered The Catcher in the Rye by accident. I didn't know what it was. I heard the name, I saw it in a library and I said, you know, I'd give it a try and I read this out and I think most boys probably read it when they're 14 years old, if they do encounter it and I didn't know what it was about and you couldn't really tell anything by the title, but there was something about it that when I was reading it, it really felt like being spoken to and my reading was so limited, I didn't realise that books could have been like that, you know, cause I'm so accustomed to the more flowery type of complex literature. and this one was just like a guy, a teenager, speaking about spending three days in New York or whatever and just speaking about what's on his mind and I saw the books that were similar to that and then I discovered the horror genre which is Stephen King and I read a lot of that at the time. So that's kind of like how my reading started out.

Jack Wrighton - 9:19

But of course as you pointed out with games there's a great storytelling tradition there, you know, how anyone comes by stories, you know, it doesn't have to be books, it can be television, it can be film or games. I've certainly spoken to a couple of authors on this podcast who have said, "Well, actually, when I was younger, you know, I loved stories, but how I got those stories weren't necessarily through books." and I think it's that, you know, anything that's kind of good for the imagination when you're young, it's all good, you know, it's about finding what's right for you and, you know, games in terms of world building are, you know these days a step ahead of the rest and that's you know no offence to writers out there but you know that they are you know they're really they're adding to that sort of great storytelling tradition so the games you went for then were these kind of quite sort of story heavy games as opposed to…

Kevin Jared Hossein - 10:09

Yeah as opposed to like shooter em ups or something like that, yeah that were like yeah really heavy on story.

Jack Wrighton - 10:16

It's interesting that you say I must confess I've never read Catcher in the Rye and that you mentioned the sort of of age of kind of 13-14, because I have heard people say that it's sort of you know those teenage years is kind of the time to read it and some people have said that they've gone back to it later on and they sort of haven't connected to it in the same way. I think that first connection you have with a book that you feel speaks to you in some ways is always a very, a very sort of potent one and it's a potent memory and do you remember when the sort of the last time was that you connected with a book in a similar way and kind of more recent reading?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 10:51

You know, coming back to the Catcher in the Rye, I did read it again, maybe in my 20s and, you know, there was nostalgia to it. I can remember some parts were, you know, word for word, but sometimes it just felt really cringy and it wasn't really like that it aged badly or anything like that. I think I just aged and at first you see the protagonist holding Caulfield as like a heroic character and then I think as you get older, when your own personality changes and you go through your own life changes, you start to, you begin to question, why did you think of him as heroic because he's, he's really, really deeply flawed. He wants to be heroic. He wants to be like the hero of the story, the main character of the story and I actually think that's a beautiful thing when you revisit a story, because even though like I don't fully connect with it right now, I would still recommend it to, you know, to let's say a 14 year old. I might recommend it to someone in their 20s, maybe just to check it out.

11:54

But I think that it works kind of like when you see a movie when, you know, you're a child and then you look at it like, I can't believe that I thought this movie was good. Because you know, your tastes change, your developer gets refined, and you simply have become more exposed to not just other types of media, but just situations in your life. So when you see characters from these books, not to say that it is not timeless, but it is… they are malleable. They do change with your life. There are some that they do remain static. Like, as I said, maybe like The Hobbit may remain static throughout because that story is so, you know, it's grounded within our imaginary world. But yeah, so I think it's still not a bad thing if you cannot fully reconnect with our characters as you get older.

Jack Wrighton - 12:47

That's a really nice point. I think when a character is well drawn, when they sort of have life kind of breathed into them is yes, you can go back to them and, you know, kind of re-establish a different relationship to them, which really says something about, you know, the character that from a different angle, you can, you know, you can see something, or it's even like reading a rereading a book in actually a short space of time sometimes you can come across things that somehow before you you didn't quite catch and you know with Hungry Ghosts there's obviously you know a sort of a cast of characters with that for you as a writer when you're sort of approaching i've met some writers that kind of with characterisation they approach it by sort of they kind of create the characters in their head and then they sort of write the book or they kind of let the process of writing sort of flesh out the characters do you have a particular way of approaching that or do you just write and then see what comes out?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 13:41

Usually the books, if I were to start a story, it could start either way. A lot of my stories are pulled from real incidents, so it's not recorded like one-to-one or anything like that. There's still the creative aspect of it. So for example, my short-story passage that I won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize for. That was based on an incident that I read about when I was 16 and I really wanted to write a story about that but I just couldn't find the lens to work it through and a decade unchanged later I met a man who worked in a forest he was like a forestry officer and I was so taken by how this man spoke and his views that I said, "Ah, this is the guy who's going to narrate the story." That I wanted to write this whole time. With Hungry Ghosts, it actually started with one character, the character of Marlee Changoor, and everyone else branched out from her. So even though she is not particularly the main character in the book, but she does embody many of the aspects that I believe in the term Hungry Ghost, you know, something that is forever wanting but never fully satisfied stands for. So it does differ.

Jack Wrighton - 15:15

So for Hungry Ghost, you know, that was the kind of the way into the story as it were, you know, like with the passage, you know, you found the kind of moment where you're like, "Ah, this is the..." as you said, the lens, the kind of the way, yes,, that must be, I don't know, quite an exciting moment, I imagine, when you sort of, you think, "Ah, this is, yeah, this is it."

Kevin Jared Hossein - 15:36

Yeah, I wrote that in one night.

Jack Wrighton - 15:38

Oh, wow, oh, wow, okay, that's a very, yeah, a very… is that, in writing, do you tend to sort of, you know, some authors I've spoken to, it's kind of relatively short intensive bursts or it's a kind of a slightly more drawn out process? Would you say you fall into either camp or again somewhere in between?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 16:01

It is usually what happens is that I, for Hungry Ghost in particular, I did a lot of research. So I did a lot of interviews, went through archive information, and that took a pretty long time. In fact, I got much, much more than I would have used in the book. Then I wanted to put everything in the book, which was wrong because then the book would have been extremely bloated, which it was for a time until it got edited and because you also feel like you have to honor everybody you interviewed, you have to put it there, honour their time at least. But there's this long drawn out process in a way. But there's parts of the book, like if I was to write a skeleton, like a skeletal plot of it, there's parts that I would say are like mini climaxes throughout the book and these are parts that not necessarily would be plot climaxes but they will be high points in my mind. Like this is a really exciting part for me to write. So there's a part where some young boys, some teenage boys, take some mushrooms in the novel and they begin to hallucinate and I've never actually written anything like that before but that to me is like a high-point, no pun intended. So to me like that would be written in a very short burst, sporadic and that should be, I'd be like really excited to hit those points there. So I work up in anticipation towards those points, be like oh tomorrow I'm gonna… tomorrow's that scene, I'm gonna write that. I get really excited, yeah.

Jack Wrighton - 17:41

That sounds almost like a hiking or something where you know there's kind of you know people might go I really love this bit of a hike but obviously I have to get to that point first yeah but that's your kind of drive to get there because I imagine you know there's points where you're getting from sort of a to b and that's the middle section is kind of a bit a bit knotty and a bit sort of frustrating and maybe hard to hard to work through.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 18:05

Yeah and then later on you you still have to work through it and then later on you could smooth it out, edit it and some parts may be a bit of a slog. As in kind of like a hike, as you said like okay I want to get to this point I can see this view, oh but I have to go through this muddy terrain first. Except you know with writing you can always go and smooth it out and you know make the scenery a bit nicer and integrate those aspects a bit more. But the point is that you have to make it to the point you have to finish what you're going to do.

Jack Wrighton - 18:37

Yes, which takes quite a bit of discipline, I imagine, to get to that point.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 18:40

Yeah.

Jack Wrighton - 18:41

We've talked about what you read and how you enjoyed stories when you were younger. Now, the Kevin of today, are you much of a reader now? Do you have time for much reading, or is that time mostly taken up by your own creative process? How would you describe yourself now in terms of books?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 18:59

Oh, that's an interesting question. So usually, if I'm working on a book, this one in particular, I try to keep it a few months, at least with the writing process, the first draft process. The reason being is, and I'm sure other writers run into this issue as well, you tend to unconsciously integrate the good things about books that you're reading into your book. "Oh, my book could have this too!" Even though you try to make this weird patchwork of this and that, and it just becomes something derivative in a way. So I like to read poetry instead, if I'm in the process of writing instead of fiction, or I like to read nonfiction. So fiction for me is like in my, probably if I'm in a research phase or non writing phase or even just an editing phase where I already have, you know, draft done. Obviously there's authors and books that may have informed or influenced my style. But I try to avoid it because I know I do have a bad habit of trying to integrate certain plot points into my own studio to make it fit. So it does not end up fitting in the end.

Jack Wrighton - 20:15

Of course, yeah. I imagine anybody who's a reader or a writer, there's kind of a sponge element to that. When you enjoy a story, it kind of all gets soaked in. I imagine when you're trying to write your own that can kind of get in the way of the process and you mentioned non-fiction as well because am I right in saying for a long time or maybe you still are apologies I've got this wrong but you're a teacher as well as a writer.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 20:41

Yeah, yeah, yeah I've been more consumate tutoring nowadays because of the time, yeah so but I do still have that aspect to me yeah but while I was writing the book and throughout editing yeah I was still teaching full time.

Jack Wrighton - 20:55

And did that… because it was biology, is that correct?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 20:58

Yes biology.

Jack Wrighton - 20:59

Biology, yes. Because you mentioned as well when you were younger you had those kind of non-fiction books, so that love of non-fiction then remained. Was that kind of one of the spearheads that led you towards teaching biology as well?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 21:12

It was in a sense. I did enhance my teaching of it because I was, as I said, when I first started reading I had these childcraft books and one of my favorite ones was one called the Green Kingdom and it was about these plants, you know, which could be seen as the most boring thing sometimes. But there was a way in which when they wrote it, and I didn't think about this until much later, but there's a style in which they wrote it and they used quite simple but beautiful language actually to describe some of these plants and they related it to folklore of different countries as well and they did have historical context and even as a child you just can absorb it and as I got older I noticed that let's say Charles Darwin for example when he wrote The Voyage of the Beagle, like his trip to the Galapagos Islands, it's written in very beautiful language, very descriptive and this is because you want people to get excited and you want people to get, you want to touch upon this imagination that they have and not have just like cold staring facts. You want to hit something emotive in them and a lot of science writers do that. So in a way it is linked like that and something that very early in my career of teaching, I read a book called The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and it’s a memoir by Jean-Dominique Bobby. He was a fashion editor and he got a stroke and all he could have done was blink his left eye.

22:54

So he wrote the book with his left eye. So he would blink and then they would copy the letters one by one. At the time I used this to teach about like the cerebrum, the medulla, the spinal cord, you know, things like that and I would read parts of it for my students thinking back on, yeah, science is not just cold, hard facts. Yes, there's the factual part, but there's also the part we have to be able to communicate these ideas quite efficiently, just like literature does. And some nonfiction books do that quite beautifully. So they do go hand in hand. So yeah, they do influence each other. My love for like nonfiction books, at least the ones that integrate that sort of literary communication to it.

Jack Wrighton - 23:43

Absolutely. Yeah, nonfiction books can be, you know, just as beautiful than fiction books and I suppose science in a way is a form of storytelling. I might be getting this completely wrong as not a scientist myself. And of course, you know, Hungry Ghost is very influenced and centered on the kind of the natural world. So that feels, you know, fair to say that that aspect of you obviously fed into the to the writing of Hungry Ghost as well.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 24:08

Yes, yes it did because a lot of what i studied was ecology so you'll find a lot in the book.

Jack Wrighton - 24:15

And in terms of you now as a reader if again we're sort of in this imaginary bookshop where i'm getting you to you know talk about the books that you've loved in terms of recent reads things that you've read whether fiction or non-fiction what books stand out for you?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 24:30

Sure there's one called Chernobyl Prayer: Voices from Chernobyl and it's by, I hope I’m pronouncing this correctly, Svetlana Alexievich and it really is just a collection of monologues based around people who would have been on the site or the periphery of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and these turned out to be surprisingly poignant because there's very little editorial input from her. She knew however, the order in which to put them in, in order to maximise the impact. So I read this before I saw, you know, there's a HBO Chernobyl series. I read that and I thought it was mind-blowing. I thought it was something that maybe everybody could read with respect to probably any natural or man-made disaster because there's always this very, very human collective behind it. Another recent one I read was The Sound of the Mountain by Yasunari Kawabata, a Japanese author. It's a book that came out many, many years ago and I bought it as this guy was just, he was moving and he was selling off his books and I was just like, okay, I'll buy that box of books.

25:58

I, you know, whatever is in it and I saw this and, and then I, you know, we were going on a bit of a road trip and I just read it in the car and it uses, I guess what people would call a economy of words and there's always something that interests me about some Japanese lone words, where they have words to describe emotions that we don't really have a word for, you know, we might have like a sentence or so on, but they have like these very complex emotions, very nuanced emotions that we would have to describe in like a paragraph and they might have a single word for it. So like in this novel here, there's an old man who's in his sixties and he's approaching that and he discovers that his son is having a fear with his daughter-in-law and as a result, the old man gets very close to his daughter and uncomfortably close, where he develops feelings for her. I wouldn't even say in a gross way or anything like that. It is actually quite wholesome how he tries to comfort her and tries to get his son to, you know, to stop doing this to his wife. But it's a very, very complex emotion that could have gone very, very wrong and/or that you would use a multitude of words to describe such a thing. But The Sound of the Mountain does it using nature and using domestic actions and lifestyle to describe this. I think it is also worth the read to go through that.

Jack Wrighton - 27:45

Yeah, that sounds really interesting and it's always fascinating the differences between different languages because I think, and again apologies if I'm wrong, but I remember a couple of years ago there was a lot of different books that came out that were to do with sort of mindfulness but kind of different countries sort of approach to mindfulness and I think one came out that was about sort of walking in nature but it's from a Japanese concept which I think the translation for the nearest we can get in English is tree washing or kind of tree bathing I think is the word.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 28:21

I think I’ve heard of that yeah. I can't remember the actual Japanese word but I remember.

Jack Wrighton - 28:23

No, no, no typically I can't remember the actual word but yes and you know I thought that was um once you know the concept, a word for it makes perfect you know perfect sense and it's when it speaks to an element that you know I think we all have that that kind of desire sometimes just to kind of get out in the natural world and enjoy it for no particular purpose you know not uh not even just to sit and have a picnic or something but just to kind of walk through it and uh it's a lovely moment when you kind of come across that another language has actually found a vocabulary for that that maybe English is lacking.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 29:04

Yeah, and the term tree bathing or washing may sound awkward, but if we think of it as like cleansing or like washing away, taking more shells or something, it makes sense. But in the English sense of it, it does sound awkward, I'm sure in the Japanese context it's more poignant.

Jack Wrighton - 29:27

Yes, yeah, absolutely. That's the thing, the translation can never quite, you know, nail it with so much as, you know, lost there and one thing actually for authors, do you find that are there moments where kind of the concept of something is very sort of clear in your mind, or even a scene, but then actually the process of kind of translating that to on the page, that there's kind of that gap between what exists in here, because of course in our minds something can be four dimensions as it were, or three dimensions, but that process of transferring it over to the page, do you find this is that almost kind of like a translation from one sort of state to another?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 30:09

Yeah sometimes that you, especially when I write, okay so I was reading about, I read this book, Our Souls at Night, and it's really, most of it is really just dialogue between an older man and a woman. These two American neighbors and both their spouses have passed away, and the woman suggests to the man that he could come over to sleep, not to have intercourse or anything like that, but simply that they would sleep together in a bed, and it might make the night's pass easier. You know, it wouldn't get so lonely. That actually develops into a kind of a complex thing around how there's rumors about them, you know, things that, but they end up learning about each other. But I was reading about the… and how the book is written is really just dialogue. Like most of it is dialogue because a lot of it is talking and the author, Kent Haruf, when I was reading about his style in writing, he used to go to a tool shed. So it's similar to what you have there.

31:16

This is actually probably why this one came to mind. He would go in total darkness and he would have his laptop actually and his laptop also produces light. So he would have on this cap, and you pull the cap over his eyes, and he would type, type, type, type, type and it doesn't matter if it had typos or if it wasn't edited properly, but he just typed the dialogue as it appeared in his mind and sometimes when you have things in your mind and they get translated to the page like that, it might not be 100%. But that's where editing comes in. For me, I do something similar where I write in darkness. I don't cover my eyes or anything like that. I try to erase everything around me, but I like to have music playing and I would sometimes think, oh, maybe this music fits this person's frame of mind at the time and you know, of course, when you have music, wild images may come into your head. Not all of it may be translated as the type of imagery or, you know, through the words that you have there. That's fine and sometimes you might end up, if you really were to translate everything in your mind to the page, you end up with this kind of maximalist, overstated thing. So sometimes it's really best there's not 100% translation from mind to page.

Jack Wrighton - 32:43

Yeah absolutely, and yeah so writing in darkness but not not to the extremes of kind of you know… yeah that's a very interesting method I like the sound of that it's always interesting hearing you know how different people approach this. And in terms of for you, if you were to recommend a book that… we used to phrase this as a book that changed your life which I think is a very strong claim to give a book and not everybody was able to I like to more sort of phrase it in terms of a favorite book or a book that really stands out for you, or it can be books as well, but what would you be pulling off the shelf in that scenario?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 33:22

I would suggest that it might not be for everyone, but everyone should give The Road by Cormac McCarthy a try. At a surface level, it is an entertaining but bleak read. If it was very bleak, I was right, it was very bleak. If you were to read it a second time, you may notice linguistic and stylistic things that he did with the text. If you're familiar with Cormac McCarthy and he doesn't really like punctuation. So he doesn't like apostrophes and dialogue quotation marks or anything like that and that could be frustrating, but somehow with the rule it fits because it's set in a wasteland and the way in which he puts the text, the sentences, they're very brief, stark sentences and sometimes almost devoid of punctuation. It does give off that feeling that this is a world that's blown apart and things are missing. There's of course, much more to it than that. It's something that a book I do revisit from time to time to see how exactly he did accomplish this because it's another situation where he used very spare language at times, but he also used very specific words to describe things with that you may not see or phrases you may not see anywhere else. It did influence some of my writing because some of mine is ancient language and scientific language and things like that. But it is a book that I think is worth visiting at least once.

Jack Wrighton - 35:04

It's interesting yes what you say about McCarthy’s language, yes I've read… I've always meant to read the road I read Blood Meridian and that was also a kind of very, you know it's not, you know, it's not a jolly book I would say but it you know there's that very distinct use of language and um with hungry ghosts as well you know language seems to be i mean it is obviously with all books but kind of a very sort of you know considered part of it it has a very beautiful language to it and in your introduction, certainly to the proof copy I have for those who are out there listening, I think this potentially might differ to the in-print copy, but there was talk about the almost the apprehension of talking or writing about home and the kind of the language involved with that and then it's interesting that you mentioned McCarthy with sort of using, you know, phrases that might not be, you know, familiar to everyone and I was really interested in that, that there seemed to be a want to just not kind of bog yourself down in explaining that, but going, actually, no, you know, here it is, is that, you know, were you sort of inspired by that? Or did that come from a different direction?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 36:15

It did come from that in a way because in Trinidad, we, everyone speaks in a dialect called Trinidadian, Creole English and we've never been taught how to write in that language, because we've always been dissuaded from writing it or not speaking it to each other, but let's say in a formal situation you would not speak it and of course, in a school, it's more of a formal situation, so you wouldn't really learn it there and I was reading through some of McCarthy's work and William Faulkner's work and most of their work is set in the American South and they would write the American south dialect and it would be phonetically spelled and the rules would differ. I assume there's no set rule to write how those in the Midwest or so on would speak and I was thinking, well, it could be the same way here. There's no fixed rules and I think it's really wrong. One author may write it differently from another and that's fine. how dialects are, they're flexible and malleable and then when it came to the words, I was thinking about A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Mears and I mean, he made up an entire language for that and he, you know, he had different words for men, women, milk, everything and you know, he did that and people were fine. When I was really thinking about all of this, I was like, well, there's really no fear really to write our words, to write our dialect. So I said that, let's just go ahead with it. But I do know that hesitation still does exist with younger writers that I speak with from, not just from the Caribbean. I think that the more and more that they see it in print, they're more vindicated they would feel like, okay, yeah, here is fine, to write an entire book in that.

Jack Wrighton - 38:27

Absolutely, and do you think that comes from a desire for the stories to spread beyond the borders of Trinidad and Tobago, but that feeling of having to sort of, or feeling that you might have to kind of explain that, I don't know, it must be very liberating when you realise, well actually no, it is what it is, and people will understand it. It doesn't need sort of footnotes or things like that. That must be a sort of a very freeing moment when you kind of realize that.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 39:01

It is, especially when we're given, let's say older books by Caribbean authors like Sam Selvon, who did A Brighter Sun, and maybe older editions of like A House of Mr. Biswas. You would find glossaries at the end of the book. Very rarely you'd find footnotes, but they would always be a glossary as if, "Oh, this is the other language." And not that it's right, but I understand why back then it was like that. But the publishing world has changed since there's become more accepting of different dialects, different cultures, ways of life of putting them out into the world, unapologetically.

Jack Wrighton - 39:49

Absolutely and of course language is a far more fluid and living thing than kind of our social and political ideal, ideas of formal language or informal things like that. Particularly I think with fiction but also non-fiction as well it's kind of very important to kind of break those ideas down because they are learned as opposed to kind of inherent and of course, okay, so those are the books that have had kind of a big effect on you and of course, we've talked little bits about it as we've gone through, but now it's time to turn obviously to your book, Hungry Ghosts. And if you were in a bookshop and you were putting it off the shelf and handing it over to someone and you were going yourself to tell them about the book and not to sell it to them, let's say, but to just kind of tell them about it, what would you you say? Tell us about Hungry Ghosts.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 40:43

I would tell them to imagine the Caribbean as how it may be depicted to them, which I imagine it would be in like airport ads or postcards. They can't probably imagine that and I guess imagine what it might've been like 80 years ago, 100 years ago and you know, nothing really might come to mind at the time. Even if you ask a Trinidadian that, they might know. I had a big idea. I didn't know myself until I did some research and I would say this book is a portal into that specific time. Hungry Ghosts is a portal to that darker part of the Caribbean. I imagined Hungry Ghosts to be the end of a very dark chapter of the Caribbean and the start of a new one. Because the book is very bleak, but I like to imagine this till a small slip off towards the end, but there's also the fact that I would want it to imagine that not all Caribbean people are the same, not all are the same and reading this book here, you get an idea of not just the various cultures that would have been there from the beginning and these cultures, the interesting thing about it is that none of them really came, I would say, on their own will, really. They were brought here and they were never meant to be a civilization. Imagine a bunch of people together that really never meant to be a civilization and now they have to try to be or at least pretend to be so that the island could hold itself together and I really aim for it to be an entertaining read, something that is emotive, but something, as I said, that would be, as I said, a lens to that part of the Caribbean and yeah, hopefully that you would find some characters in there that I believe that you would love them at first and then you would totally change your mind about them. So if you want to read a book like that, where it's really focused on character, but there's a bit of, let's say, a bit of detective noir, a bit of crime fiction in there as well, a bit of mystery, and a bit of coming of age as well, then yeah, all of that is in Hungry Ghosts.

Jack Wrighton - 43:19

It's one of those wonderful books. Obviously you have some books that, I suppose, although again I say this as someone who has not read Catcher in the Rye but you know seem to find kind of very honed in on one particular character and it's all through them whereas Hungry Ghost you know there's a real sort of ensemble of characters it's you know it's about many different people and you know even some people who you might sort of meet only for a short period of time they sort of really come you know come through as characters and did you always know you wanted that kind of ensemble aspect or did that just come as part of the writing process?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 43:53

It came in the beginning pretty quickly because as I was writing I noticed that I really wanted to at first focus on just the rich and the poor, but then it kind of turned into who was allowed into civilisation, who wasn't, who was allowed to buy a house, who wasn't, you know, things like that. But everything connected in a way that it was like a ripple effect. One character made something that would influence a character on the other side of the spectrum, so to speak and that was sort of the aim of doing the kind of ensemble, roving spotlight aspect, because there's many different cultures and lifestyles and issues at play here, and many different personalities that have been subjected to many different life-changing decisions or traumas and pasts and pains that I wanted it to show and this occurs through mostly the 1940s, the present day of the novel. But there's also like a few flashbacks at the beginning of each section that gives you the deeper aspect of the world that these characters live in and you get to understand them a bit more and they may break, you know, end up breaking your heart a bit because you want to really root for some of them but they just don't do the right thing.

Jack Wrighton - 45:23

They do, you know, again that's a sign of a brilliantly complex character and a very you know real-to-life character because that's true of people. We say, you know, they don't do what we think they should or we'd like them to do and that's you know kind of one of the wonderful things about a very complex, not in the sense of know complex to read but a story which has kind of all these interactions with these different characters and their environment and it's interesting what you say that when you were looking into the history you said even history that a Trinidadian might not be you know completely familiar with. So was this quite, the process of writing this and doing the research was it quite a learning curve for you or you know did you come across things that surprised you in that process?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 46:09

It was because the initial aim for this book, it was for an article, like a non-fiction article, just about village life and then, you know, I started getting all these stories and I became really, really intrigued and realised that this was a whole world that I, not that I didn't know, but that was maybe sanitised to me. me because if we were to learn about this in a history book, you may see some of these same characters with a smile on their face in the illustration. You wouldn't really know, yes, you would have the overall timeline or so on, but you wouldn't really know the day-to-day lifestyle and yeah, knowing this and putting it down in people, because these would have been my ancestors, but also solidified the kind of oral storytelling traditions that we have here, where a lot of stories are just simply not written down. They're just any memories of the older generation. So I, as I said, I felt a responsibility in a way to put all of these things in the book, which I couldn't. So, you know, it had to be edited down, but I think in the end, I think the point would have gotten across that people wanted to make when I was interviewing them.

Jack Wrighton - 47:29

Absolutely because I've heard other authors say that fiction can be a wonderful way of fleshing out or filling in the gaps in history or the things that people may not be aware of. Because you can read a short sentence about the barrack, the place where the Saroops live, but obviously you know in a story you can kind of see what that would be you know reading a sentence that you know says that is very different kind of getting a sense of what that environment would be like you know people's lives played out in these places so a sentence or a footnote in a history book can't really do justice to that.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 48:06

Yeah it would and you wouldn't even find a photograph of like a room of the… you might see like a photograph of the external part but not a room nobody would would have gone and made an illustration of that. You can't make an illustration based on someone's memory, who may have lived in one or visited one. So yeah, there's a lot that is lost, but that you can paint a portrait with it using the words and descriptions.

Jack Wrighton - 48:34

Yes, and bring that situation to life. Looking at the time, we're unfortunately approaching the end of our conversation. Before we go, would you mind, Kevin, reading a segment from Hungry Ghosts for us?

Kevin Jared Hossein - 48:50

Sure. So I'm going to read from the first chapter of Hungry Ghosts, but from the beginning, it’s a chapter that's called "A Lost Prayer." and in this chapter, there's a very affluent, childless couple named Dalton and Marlee Changoor and one night, Marlee, who is his very young wife, finds out her husband has vanished all of a sudden during a thunderstorm and as she doesn't really look very hard for him, it's as if she's glad he's gone or kind of relieved. So in this small portion of the book, we follow Marlee as she awakens the next day.

49:37

The morning after, Marlee went downstairs to prepare breakfast. Dalton wasn't there. Usually he would be at the kitchen table with his bifocals, skimming in the newspaper. He brewed his own coffee and drank until his nerves were shot. Preferably imported Arabica to the locally grown Robusta. Marlee maintained the house, did the washing, the folding, the sweeping, the dusting, chopping, cooking, the baking. Did it for her own sake at least. There were never any guests, soirees, coffee clutches, birthday parties at the Changoor estate. The living room, kitchen, bedrooms, staircase only held memories of them both. Because of this, the house always felt like some concealed shrine. The wordless stillness of the house now made the gloom of the air more apparent. It silenced wholly and eerie. For most of the day, she was a ghost, roaming a haunted manor. If he wasn't in the kitchen, perhaps he was in the outhouse, a single-roomed shed that he had fashioned into some sort of strange sanctum, a nymphium that held nothing but a giant oil painting of a Chinese goddess. He made it clear Marlee was never to enter unless he was there too. As if she were too profane for it, the goddess, like his dogs, had been there before her. The goddess, draped in lavender and topped with a phoenix crown, was surrounded by four jade maidens and giant messenger bluebirds. Marlee very slowly turned the knob, tipping the door open, dust wafting like snowfall within the dim, tomb-like room. Dalton was not there. The goddess and her maidens glared at her sternly, as if she had interrupted some invocation. It was only recently that Dalton had shared the goddess's name with Marlee. Zhi Wangbo, Queen Mother of the West. One day, he admitted that his mother's soul had been absorbed by the painting and spoke to him through the canvas. She also learnt that the apparition had once been impressed with her and even suggested Dalton's marriage to her, but no more. His mother in the painting now saw Marlee as a liar and a charlatan. That woman simply isn't devoted Dalton. He confessed that there was little he could do to change his mother's mind. All of this he had divulged unprovoked. Marlee married Dalton knowing he was so unsound of mind, but his condition had significantly worsened over the past five years. Paranoia, dementia, monomania. She wasn't sure how to describe it. He had rooms with towers of newspapers and magazines and boxes and all sorts of ephemera flew into rages at the slightest mention of tidying those rooms. The house itself was a hodgepodge of things foreign and colonial and antebellum and pretty and gold and red and scintillating. It was ungainly and disgusting, just like him.

53:06

So yeah that's just a taste of the book and from there yeah we know that something clearly isn't right in the Changoor estate and all goes downhill from here.

Jack Wrighton - 53:22

Well Kevin thank you so much for that reading and thank you for joining us on the podcast. Hungry Ghosts is available, it's out now either at your local independent bookshop or wherever you decide to get your books from and it's available in the Mostly Books store and on our website as well. Kevin thank you so much for joining us on Mostly Books Meets.

Kevin Jared Hossein - 53:41

Thank you so much for having me and it's been a pleasure.

Jack Wrighton - 53:46

Mostly Books Meets… is presented and produced by the book selling team at Mostly Books, an award-winning bookshop located in Abingdon, Oxfordshire. All of the titles mentioned in this episode are available through our shop or your preferred local independent. If you enjoyed this episode be sure to check out our previous guests which includes some of the most exciting voices in the world of books. Thanks for listening and happy reading.