- Benjamin Heckendorn

- An electronics hacking entertainment guru

- Former host of Element 14’s “ The Ben Heck Show”.

- Chris Kraft

- A tinkerer currently working as a software engineer in the financial services industry

- Extensive background in 3d printing and building anything that seems interesting

- Past two years

- Both where last seen on Episode 75: Does the simulation match reality?

- Ben has moved on from hosting "The Ben Heck Show"

- Chris has been experimenting with SLA resin printers

- Hangprinter

- A very simplified explanation is you take a delta printer but instead of having the three motors that are attached to the side frame you instead locate those motors wherever and have wires/cables/etc that run up to points that you mount

- Some videos that show how it works

- The first new/interesting thing Chris has seen in awhile

- Project is open source so people are free to contribute and find ways to improve the design

- One thing I feel is potentially a missed opportunity is the focus is on making it cheap

- ODrive

- Designed to give motor control to hobby grade brushless DC motors instead of stepper motors

- Hackaday.io project

- New Makerbot printer named "Method"

- Non-heated bed is a “feature”?

- Latest design seems to prefer technologies that Stratesys can or already has patented

- Consider the humble Luffa

- For a long time manufacturing has mostly used subtractive techniques

- Until recently most manufacturing was about taking raw materials and cutting, bending, etc into the desired pattern

- Look at that infill

- Additive manufacturing is really different when you think about the possibilities

- What if we could use CRISPR to "reprogram" plants to produce other things? Like growing a replacement organs, body parts or something else completely?

Creators and Guests

What is Circuit Break - A MacroFab Podcast?

Dive into the electrifying world of electrical engineering with Circuit Break, a MacroFab podcast hosted by Parker Dillmann and Stephen Kraig. This dynamic duo, armed with practical experience and a palpable passion for tech, explores the latest innovations, industry news, and practical challenges in the field. From DIY project hurdles to deep dives with industry experts, Parker and Stephen's real-world insights provide an engaging learning experience that bridges theory and practice for engineers at any stage of their career.

Whether you're a student eager to grasp what the job market seeks, or an engineer keen to stay ahead in the fast-paced tech world, Circuit Break is your go-to. The hosts, alongside a vibrant community of engineers, makers, and leaders, dissect product evolutions, demystify the journey of tech from lab to market, and reverse engineer the processes behind groundbreaking advancements. Their candid discussions not only enlighten but also inspire listeners to explore the limitless possibilities within electrical engineering.

Presented by MacroFab, a leader in electronics manufacturing services, Circuit Break connects listeners directly to the forefront of PCB design, assembly, and innovation. MacroFab's platform exemplifies the seamless integration of design and manufacturing, catering to a broad audience from hobbyists to professionals.

About the hosts: Parker, an expert in Embedded System Design and DSP, and Stephen, an aficionado of audio electronics and brewing tech, bring a wealth of knowledge and a unique perspective to the show. Their backgrounds in engineering and hands-on projects make each episode a blend of expertise, enthusiasm, and practical advice.

Join the conversation and community at our online engineering forum, where we delve deeper into each episode's content, gather your feedback, and explore the topics you're curious about. Subscribe to Circuit Break on your favorite podcast platform and become part of our journey through the fascinating world of electrical engineering.

Welcome to the MacroFab, the Engineering podcast. I am your guest, Benjamin Heckendorn.

Chris Kraft:And I am your guest, Chris Kraft.

Parker Dillmann:And we're your hosts. And

Chris Kraft:we are the hosts. Sorry.

Parker Dillmann:Parker Dillmann. And Stephen Kraig. This is episode 153.

Stephen Kraig:Benjamin Heckendorn is an electronics hacking entertainment guru and former host of element 14's The Ben Heck Show, and he likes to smell his own farts. Chris Kraft is a tinkerer currently working as a software engineer in the financial services industry. Extensive background in 3 d printing and building anything that seems interesting.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I think it's important to have a closed feedback loop on your farts so you know just how bad they are. That way you can analyze them?

Stephen Kraig:Do they evolve over time? Is are you keeping track of them?

Benjamin Heckendorn:On what you eat, you know.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. That's that's one of the inputs. Right. Right.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So both Ben and Chris were last seen on the podcast on episode 75, 5, does the simulation match reality? So Ben and Chris, what have y'all been doing since then? It's been, like, almost 2 full years.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Really? It's been that long?

Parker Dillmann:It's, like, 2 summers ago.

Stephen Kraig:That was back in the bomb shelter.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh, god. That place, like, that got destroyed in the flood, didn't it?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. You guys and and you guys either had right before or you were going right after to fly in a B 17 bomber. Right?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. Yeah. That was pretty awesome.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh, yeah. Yeah. Because we had to go up into Houston then we went back down to Galveston.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. We went to the, we went to the Battleship Texas.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. I still have, my my wallpaper on my computer. My big computer is, from that flight.

Parker Dillmann:Nice. The Battleship Texas flight?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. When we flew around in a battle ship. Smelling your own farts. All I could smell was farts and diesel fuel as far as the nose could

Stephen Kraig:see. Oh, fantastic. So so yeah. What's what's been up since then?

Benjamin Heckendorn:My blood pressure? Actually, it's gone down. So it went up then down.

Parker Dillmann:Well, after after because you're not you're the former host of the Element 14, the Ben Heck show.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. I stopped filming the Ben Heck show in June of 2018. So since then I've been working on some other projects that I've been wanting wanting to improve over the years but never had time to. And, yeah. Just kind of semi retired.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So I well, I I work, like, 7 hours a day now.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. As opposed to, what was it before?

Benjamin Heckendorn:8? Well, I mean, there was there was a time when I was doing the show full time and working on pinball machines on top of that. So there were actually some pretty stressful years. Probably like 2013, 2014 were pretty busy for me, so it's nice to kinda slow down.

Stephen Kraig:Right. And and the, I think we talked about this back in episode 75, but the pin hex system is sort of named for you. Right?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yes. Although I I don't like that name even though well, Parker and I both designed it, but whatever. Somebody called it Penn Heck, so great. I didn't I didn't want the Ben Heck show to be called the Ben Heck show.

Parker Dillmann:That was not

Benjamin Heckendorn:my idea either.

Parker Dillmann:I think my favorite thing was about that at near the end, y'all had a contest to change the name.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh, of the show?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Of the show. And then it once said to keep the name.

Benjamin Heckendorn:But they were they wanted to change the name because, you know, they knew I was leaving in a year.

Chris Kraft:Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. Me leaving the show was a long a long thought out process. It was like at least a year and a half. So I think I think they should have stuck to their guns and just changed the name then because then they had to scramble, last spring to do it.

Stephen Kraig:So I actually haven't looked into it. What what's it called now?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Now it's called element 14 presents. So what they did was they hired a whole bunch of different people to create content. And so what they do is that I think they have like, like 10 to 15 people making stuff now, but what works works better about it is that each person, since there's so many people working on things, each person doesn't have to create something every week. It's basically, hey, whose project is done next? And then that's the video they produce.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So they still have a weekly release schedule but they're not burning out, you know, Ben and Felix.

Parker Dillmann:A single person?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Because you were doing you were doing a lot of work to have fresh and interesting content every single week.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. And then if you do multi part episodes or like, oh, it's part 3 of 3 building this clock or whatever. People viewership drops off very rapidly when you have multi part episode projects.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. That's something I think is interesting when you look at because you're now posting just your own videos on your own YouTube channel, and a lot of people are saying not a lot. A lot of comments are, oh, this is so much better, and I don't want to reply to people in comments because it's just a minefield, but it's I wanna kinda say that the show was the way it is because it had to be that way for the viewership that they were going after. And your private channel is great, but you can get away with things that because you're not trying to please that audience.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, not just pleasing an audience, but, you know, when you're representing a large company, they want to create videos that meet a certain production standard. You know, they want the audio to be good. They want the lighting to be good because the way the videos are made reflects on the company. Whereas, when I make my own videos, I don't give a fuck.

Stephen Kraig:You can go one way or the other.

Parker Dillmann:Do you get the curse on your on your YouTube channel?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Actually, I don't because I actually monetized it. My channel is doing actually really well right now, strangely. Because, yeah, it's like I just make long videos with all the detail the way I want to. And, yeah, actually, my videos now are more popular than the show was in the last

Chris Kraft:couple of

Benjamin Heckendorn:years. It's weird. Yeah.

Chris Kraft:I think the point I'm trying to make is that the people who like those long, more detailed videos, but when you try to do that on the show, there were people complaining about it. So it's like, you can't win.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, and also, this came from the revision 3 days, but there was definitely a push to keep everything no longer than 20 minutes. And so you end up having a lot of you have to edit out a lot of the, steps and basically show show just the overview of it. But the thing that the irony of that is YouTube rewards watch time more than views. That's why, like, let's plays and whatnot became so popular on YouTube because it's really easy just to sit there and play video game for an hour and create an hour long video, which actually YouTube will reward that over, like, an amazing 2 minute animation. So I guess my point is having longer videos on YouTube is actually desirable, but we were trying to keep things at 20 minutes.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Well, it used to be the YouTube algorithm was, like, going towards 12 minutes was like the ideal time frame and now it's changed. Well, it probably changes like every week. Yeah. The AI at YouTube.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So I just I bought a 4 ks camcorder from Best Buy And that's that's cool because you can just, you record in 4 k, but then you make a 1080p video, but if you want anytime you can basically zoom in 200% for free because you're recording twice the pixels. And then I just I just clamp it to the desk, turn on my overhead lights, which I have pretty good lighting in my basement, and then I just talk. I did get feedback that it it's in stereo and people are like, oh, your voice is either to one side or the other. And I'm like, well, I'm not gonna wear a laugh, damn it. However, in the future videos I will mix them down to mono so you can't tell.

Parker Dillmann:Probably makes sense. I guess that's the speaker oh, not speaker. The microphone is a stereo microphone.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Right. And the camera is either to one side of me or the other, which I guess headphone, listeners noticed it more than anyone else. But

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I think podcasts are mono.

Stephen Kraig:They should they should be. Yeah. There's no there's no I mean, what's the point of having a stereo voice? You know, like it

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, you can you can put 1 person on the left and one person on the right. So there's a little bit of separation.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. You you can do that, but but a lot in a lot of ways, it starts to get disorienting when you when you do that. So, it's a it's a lot easier to let, I guess, whatever the room is doing dictate where the people are as opposed to like artificially pushing them to one ear or the other.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Okay. Chris, you should tell us what you've been up to since the last podcast.

Chris Kraft:Let's see. I I dabbled in resin SLA printers, But I haven't done it much just because after a few prints, the print quality is absolutely astounding. I mean, what you can get out of a resin printer is amazing. The thing that they don't really sell you or they don't really kind of give you the whole picture is it's messy and smelly when you're working it. Like, even if it doesn't smell when it's in the printer, once you take the print out and then you go to cure it, it's that whatever that fume is.

Chris Kraft:So then you need a well ventilated area and the you gotta wear, gloves. Well, you should wear gloves when you're handling this stuff. And, it it because it's photo sensitive, you kinda need to store it properly and at the end of the day, I just felt like as cool as it is, because I'm not doing it as a a commercial entity. I'm not selling prints to anyone. I I just, for now, the printer's kinda sit in the corner and, I don't know if I'll scavenge it for parts, but I definitely have, I've kind of have the attitude of been there, done that.

Chris Kraft:I don't need to go back right now. So

Benjamin Heckendorn:I think if if you were using it for a business like you're making jewelry or something, and you had a workflow in place, where you could easily manage all that post processing that it requires, that might be different, I think. But for a hobbyist, yeah, like it's just I I've I've I had the form 1 printer for a while, they sent me one and I actually sent it back because it was such a pain just to deal with the prints. I mean, they looked amazing but everything about it was the amount of effort it took to get the high quality prints, I did not feel was worth the high quality and for me it wasn't really what I used 3 d printers for anyway.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. I mean, it's almost like when people used to have, do amateur photography and they'd have a photography studio in their homes where they'd have a developer and the cleaner and all those steps. And that's kind of like, because you'll have your thing with a 3 d print and then you take it out and you dip it into like an alcohol bath, and then you dip it in another bath to clean it, and then you put it under the curing light. And as you said, if you had a space set aside and and, like, a ventilated area and you had a workflow set up, it's it's fine. But for me, I I just I I've done it, and I'm ready to move on to something else.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Versus an FDM printer, where you pull it off the bed and it's ready to go.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. The, is that is that for me, I guess, because my FDM printer, I print polycarbonate, and I have to, like, bake it afterwards.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Bake it?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. You have to bake it at a 100 degrees Celsius to, like, relax the plastic.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh. So it's not under tension?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. You you can do that with a lot of, newer PLA materials too, where they'll have you bake it in an oven, like a toaster oven.

Parker Dillmann:That's what I do with mine. Yeah.

Chris Kraft:My dilemma there is I I bought I went to Menar or no. Walmart, Ben's favorite, store and and bought a toaster oven.

Benjamin Heckendorn:That is not my favorite store.

Chris Kraft:And, you know, the lady at the checkout, the lady was like, oh, this is really nice. What, you know, what are you gonna cook with it? And I didn't have the heart to tell her. I was just gonna use it to bake a bunch of plastic pieces and never use it for anything else because I don't like commingling my food and my, raw plastic materials. That's reasonable.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I have my solder paste in the lowest drawer of my refrigerator.

Parker Dillmann:Actually, at Macrofab, for the longest time, we used the freezer to store our paste. Until we got enough people, we're like we're like, okay, we need a separate fridge now.

Benjamin Heckendorn:No. We can justify a fridge.

Stephen Kraig:We, at at work, we may or may not have had paste in the butter drawer in the, the break room fridge.

Chris Kraft:That's where my solder paste is. It's in the right next to the butter

Benjamin Heckendorn:and the Well, mine's mine mine's in a tube in a bag inside of a plastic bin with a lid, so you know, a couple layers of abstraction.

Parker Dillmann:It's it's totally fine.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Anyway, yes. So you guys wanted to talk about 3 d printers today?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. And, so, Chris, go ahead and take the first topic there.

Chris Kraft:Yes. So I've been following this, project called the hang printer, and I'm not sure how I found out about it initially, but, and it's probably hard for people to, it's hard to explain once you see it and it makes a lot of sense but it kind of grew out of the idea of a Delta printer where the print head in a Delta printer is kind of hanging down onto the build surface. And in a Delta printer there is usually 3 kind of legs going up that there's 3 axis that the print head hangs off of and by the way they interact, they can either go up or left or right or whatever direction. So you get all the axises that way with a Delta printer. And what with this, which I apologize, I don't have his name in my notes.

Chris Kraft:What he came up with was instead of having those legs, he basically hangs the ax the 3 axises from the ceiling essentially, and then puts the motors on the floor and he uses cables to go up and then down. And, by doing that, essentially your print area is as large as the area you can put the printer in. And you so you basically clamp it to the ceiling. So if you had a large space, you could this thing could be printing things, you know, 10, 20 feet tall. It's still kind of in in the works, so he's made a lot of progress, but it's he's still working on it.

Benjamin Heckendorn:How does the z work? I'm looking at the animation right now.

Chris Kraft:Just just like with a Delta printer, if all 3 if you were to pull all 3 of the wires at the same time, it's gonna go up.

Parker Dillmann:It actually reminds me of a Skycam that they use for football.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. That's a that's a great, example. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:So so it's just it's a system that's constantly in tension, 3 points or multiple points, maybe not 3. I'm not exactly sure how this works, but multiple cables that are in tension and basically by pulling or releasing tension on 1 or 2 or 3 of them, you can change the x, y, and z. Right?

Benjamin Heckendorn:But if it's attached to the ceiling, are those wires changing as well?

Chris Kraft:Well, the poly will be what what you'll attach something to the ceiling that then the wires go up and then over and then down to the printer.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh, so there's a pulley on the ceiling?

Chris Kraft:Basically, yeah. I mean

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh, okay.

Chris Kraft:He he has I mean, he's gone through a couple different iterations, but the one I saw, there were plates that went on the floor. Well, it it keeps changing. So, you you have to look at it to see, what the latest, iteration is. But

Parker Dillmann:And it probably depends on the the space that needs to be set up in and that kind of stuff.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. And he's done demos of it in different spaces to kinda show how it can change its shape depending on the area that it's in. I really like it because for years the 3 d printing's been kind of, at least on the FDM side, it's been, you know, we had the traditional kind of just what we're all used to now, and then the Delta printers came along and those were pretty cool, but not really the Delta design never really made a lot of sense to me in the sense that you don't need that speed for FDM printing.

Parker Dillmann:So is that the difference between, like, a normal Cartesian, printer or setup, then versus Delta is speed?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. At least in industry, like, if you look at any places, factories, where they have high speed packaging robots, you'll always see Delta printers because they can, like, pick things up and put them down and rearrange things super fast.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I think that the problem with the Delta 3 d printers is that you still can't extrude as fast as the Delta robot can move. So you're you're limited by the extrusion.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. So it doesn't make a lot of sense. But with this hang printer, he's kind of turned that around so that now because you don't have these solid structures, you can make it as big as the space that you have available. So How accurate is it? It's okay.

Chris Kraft:It's not great, not yet. He's, you know, working on that, but and that's and I mean, it's an open source project and people are free to contribute. I think, the one area where I would, like, if I actually was talking to the guy and trying to encourage him, he's pushing this idea that it's cheaper because it's simpler, which is true. But for me, the idea is so appealing that to me, I would say, don't even think about making don't focus on the fact that it's cheaper. Instead, focus on how kind of amazing this is from a from a potential functionality standpoint and focus on, you know, consistency and and, you know, the functionality of it.

Chris Kraft:And I I wouldn't really focus on the cheap stuff because there's been other projects where they've come along and said, you know, we're super cheap, and then

Benjamin Heckendorn:You mean like the peachy printer?

Parker Dillmann:I was gonna bring a printer bot.

Chris Kraft:A printer bot. Yeah. The the thing is, they work, but then, when the focus is just on the price, that's what you're kinda known as is it's cheap. And then you make all these compromises to make it cheap. And then you're suddenly out of headroom for, oh, you know, we'd really like to use a higher quality part in this, but we promised that it would be, you know, cheap to make.

Chris Kraft:Or, like, you focus on 3 d printed parts and well, maybe, you know, maybe it's worked better with milled parts. So, so that's why I'd be like, you know what? This is such a cool idea. Don't don't worry about it, the fact that it's cheaper.

Parker Dillmann:Well, that's one thing about, like, PrinterBot. Their big thing when they came out on Kickstarter was they were a inexpensive, quote, cheap, unquote, printer And the thing about doing that is all it takes is someone just to undercut you at that point.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, they were they were the cheapest printer at the time until all the Chinese clones started showing up.

Parker Dillmann:Well, that's what I mean is they started, you know, bay basically, people moved their manufacturing over to China and just undercut everyone. Like, you know, like, replicator 2 maker bot, like, got cloned to hell.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yep. That's true.

Parker Dillmann:And so if you if you if you're basically your one shining thing that your product is is just it's cheaper than the competition, Someone's gonna come along and make a cheaper version of that and that's gonna be their shining achievement of their product and if so if you're designing something that it's the only thing that's good about it is it's cheaper, you probably want to do something else.

Benjamin Heckendorn:What did they say? You need to be the cheapest, the first, or the best?

Stephen Kraig:Yes. With a product?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. 1 of those 3.

Chris Kraft:And again, I would say, in this case, he has such a unique and innovative product that to me, that's your, you know, that's your headline feature.

Parker Dillmann:So Yeah. He's first to do this kind of

Chris Kraft:thing. Yeah. For sure. And, to me, it's just interesting because, like, I could see this, It might not be practical, but in my mind, because it's just these cables, you know, I could see a printer, you know, using like huge cranes to hold up the accesses, you know, and then have your cement just kind of blobby out of the thing so you could print, like, building sized objects.

Stephen Kraig:Which thing things of that sort do exist. Just, I don't think they use the technology of hanging with cables. And you know, what's what's sort of going through my head right now as I think about how this thing actually operates is, if you think of the build envelope of the size that the head can actually move around, it seems to me that it there would be some trouble if the head moves close to one of the where the cables meets a pulley, in terms of x y location, that you you have a lot of problems with the head potentially rotating or having an angle to it depending on how the cable actually leaves the pulley and has to, you know, come down to the head at a specific angle. It's really hard to describe this stuff using just audio, but it is But like with the Delta system, they're rigidly connected to the arms even though the arms do have the ability to, rotate.

Parker Dillmann:It I don't know.

Stephen Kraig:It seems like there's a lot of stuff to overcome with that.

Chris Kraft:But, yeah, you'll notice that even with Delta printers, the beds are always circular and that's because there is a restriction on the build area. And there is, I mean, that is one of the limitations of the hang printer. Although, I think in one of the videos, they kind of explore that and they've been working to make that build envelope bigger. But it's, if you didn't need to print something at that height or that or that scale, then I would not say it's your solution. Like, if someone's saying, oh, I want a printer for my house, I'd be like, well, no.

Chris Kraft:It's build one because you think it's cool, but don't plan on that as being your day to day, you know, go to printer.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, just convert your entire, like, guest bedroom into a ginormous printer?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. But, like, I think in in one of the examples he was printing that the Tower of Babel at, I think it was an art gallery or something. And I I think it ended up being 2 flights tall or something like that. And it's like, to actually do that with a traditional printer, even a Delta, you need physically it needs to be that tall and then, you know, the taller it gets the harder the structural stability gets.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, you should definitely include some links to videos to this printer in your topics so people can visualize it.

Chris Kraft:Absolutely. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. We'll post the links in, the YouTube videos. They look really cool.

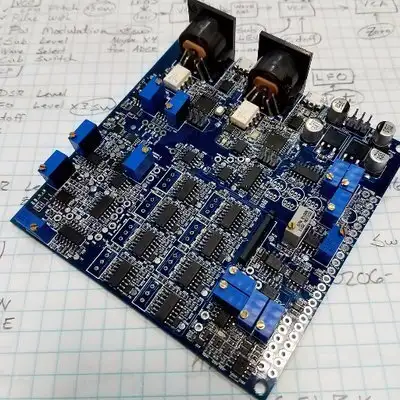

Chris Kraft:And and then the other thing that I found while researching the hang printer is his latest generation uses this, o drive from, o driver optics. Yeah. And we'll have that in the notes too. But, and it's a it's a motor controller designed to basically take, like, hobby grade, brushless brushless DC motors and give you the the kind of fine servo and closed loop feedback motor control, as an alternative to stepper motors.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, these are cool.

Chris Kraft:And I don't know how that'll work because people have been trying to use DC motors for a long time at a lower price level, but if it works it could be really cool.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Like the cupcake printer back in the day?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. Yeah. All on the extruder, I mean, all the extruders initially were DC motors and but I'm saying like just in general at a because years ago, many years ago, back in the late eighties, I worked in industry where we were using DC, large DC motors with closed loop servo feedback and all that stuff. But they were super expensive, because that kind of control was just expensive. But who knows with, you know, modern technology anything's possible.

Parker Dillmann:I'm I'm looking at the demos as, I think it's actually o drive robotics not O Driver Optics. Or Obotics.

Chris Kraft:Oh, yeah. Yeah. O Drive Robotics. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Man, this thing is fast. These are so much faster than, like, the stepper based, x y tables I've seen. This is cool.

Stephen Kraig:They probably also, stepper motors lose torque really fast with, faster speeds. I bet you these hang on to torque a

Parker Dillmann:lot further into higher speeds. And looks like he's using, like, basically, brushless motors that you would buy for RC robotic, not robotics, RC cars and planes and stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Mhmm. Yeah. That's what it's looking like. And they have that, yeah, they have that really specific sort of banana style connection.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. It was basically quadcopter motors. Right?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. But, like, beef beefy quadcopter motors.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. He's got a draw bot that looks really cool.

Chris Kraft:I mean, you definitely benefit from tapping into more commodity parts. If it works, it'll be pretty amazing, like, because these the encoders are always super expensive too, so I'm be curious to see how he's approaching that.

Parker Dillmann:I'm gonna take a look into that, in in the future. Nice. And so going off, 3 d printer topics, MakerBot came out with a new printer.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh, the MakerBot method.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, that what that's what it's called?

Chris Kraft:A performance performance 3 d printer.

Stephen Kraig:Well, what what is what is that supposed to entail? Expensive?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. A lot of us have been talking about it. We don't know what performance 3 d printer means. It's it's a confusing, term. I think it means, as you said

Benjamin Heckendorn:It's $65100. Is it really?

Parker Dillmann:I think it's it's kinda like it reminds me of a lot it's like a prosumer product.

Stephen Kraig:Well, they they say it fuses industrial performance with desktop accessibility.

Benjamin Heckendorn:It it seems well, we were talking about PrinterBot earlier, and it seems like what's happening is the remaining players are going up market. I mean, we're seeing this with BakerGear as well. They're going upmarket because the low end has been completely overtaken by mono price stuff.

Parker Dillmann:I mean, yeah, I've got a mono price printer and for $500 you cannot beat that printer.

Benjamin Heckendorn:When I would go to trade shows or maker fairs and random people always asked, what's the cheapest I can build a printer for? What's the cheapest printer? Cheap, cheap, cheap. Well that's all, you know, people always want the cheapest thing. And now you can get you can get like what?

Benjamin Heckendorn:A $175 printer for mono price?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Their low end one is.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. And the funny thing is I think it was, like, quite a few years ago, and we might have even talked about this on the last podcast, but, people are always saying to me, oh, once they figure out, you know, get rid of the steppers and put DC motors in there and do this and that, they'll be able to buy a 3 d printer for no more than what it costs to buy an inkjet printer and then they'll be in every home. And I said back then, I I I said no. They'll never be in every home because there's not a laser printer in every home. There's not an inkjet in every home.

Benjamin Heckendorn:There should be a laser printer in every home. But that's the thing is

Parker Dillmann:a inkjet printer has steppers in it still. So I don't think that's a good argument.

Chris Kraft:I'm just saying, like, the thought was if you make it cheap enough, they'll be in every home. And I said, no. It won't matter how cheap you make it because if you don't need a 3 d printer, if you don't know how to make it work, then you won't buy 1 just like not everyone goes out and buys an inkjet printer. And I said at the time, the growth area will be the prosumer because at that time the cheapest, the absolute cheapest printer you could get was like 50 or $60,000. So if you could say sell a printer for $6 this was the argument I had like 6 years ago, was if you sell a printer for 6 grand and it's capable, it has the same capabilities, you've you'll destroy the market because all those engineering firms and all those people will want to buy those printers and put them on every one of their engineers desk.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, I think that's what Maker Bot is hoping to do. You know, obviously, you know, they're not gonna buy a cheapy mono price printer, but if it's like, oh, well, well instead of having like a $25,000 Stratasys printer, here's a $65100 printer which has comparable quality. I think that's what they're going for.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. And they're owned by Stratasys now so and that's another thing I noticed was it seems like they're preferring technologies that Stratasys either already has a patent on or that they can patent, which again makes sense because Stratasys I think within MakerBot and since Stratos has bought them, I think their attitude is the the world stole from them which is incredibly inaccurate for anyone who remembers the history. It's more the other way around, but so I think going forward, they're gonna be pushing these technologies that they have patents on.

Parker Dillmann:I think it's, they're going towards reliability. Like, instead of buying a $300 Monoprice printer that you have to basically babysit it while you're printing stuff or tweak it to make sure it prints good prints. I could see MakerBot basically going, okay, let's make something that's really reliable. So you all you have to do is take it out of the box put it on that engineer's desk and the engineer hits print and it prints. Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I guess the, filament is stored in a sealed chamber so humidity can't affect it on that printer on the MakerBot method.

Chris Kraft:Yeah underneath it like under the bed it's stored.

Benjamin Heckendorn:And then it doesn't it doesn't have a heated build platform apparently?

Chris Kraft:It does not have a heated build platform. They claim that it's superior design to heat the chamber and just let the ambient temperature heat up the build platform.

Parker Dillmann:I mean, when I was printing with PLA, I never used a heated bed. I just printed on tape.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I still use a heated bed with PLA.

Chris Kraft:I use a heated bed, but I just print right on glass. So I found that around it depends on the the temperature, but somewhere around 80 degrees Celsius, a clean piece of borosilicate glass PLA will just stick to it like it's glued on.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So how are they heating the chamber? Are they is it just a sealed chamber and it heats passively from the print nozzle, or do they have some sort of active heating element?

Parker Dillmann:It's the smugness of MakerBot Yeah. Breathing into all the hot air.

Chris Kraft:It it's hard to tell because they just have some fancy animation on their website. But I my guess is there's a pelter some kind of, pelter in there somewhere and then something to circulate the the air around. That would be my guess.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So it's a miniature inverse dorm refrigerator?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Chris Kraft:Mhmm. I mean, it works. I've used Pelters to, go in the opposite direction to warm up a pie once, so

Benjamin Heckendorn:Like the kind you eat or a raspberry pie?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. An actual yeah. An edible pie.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. I almost kind of wonder if MakerBot if it's okay. So if you can make a printer that works for $300, and MakerBot's making their stuff overseas anyway, so there's not that aspect anymore. Maybe it's like, okay, if we can make a decent printer for $300 in China, but we're MakerBot, so we can make a really good printer for like $2,000, but then we'll sell it for $65100 so businesses will take it seriously.

Parker Dillmann:Oh and you know if you look at their site they're offering basically you buy this with support as well

Chris Kraft:yeah and I think for sure there's there was a point in time where, like, schools and a lot of places bought MakerBot because of that reason. You got support. It was, quote, reliable. But they had so many problems with their last generation of, extruder. Yeah.

Chris Kraft:In in the the smart extruder, they called it, which a lot of people derided. There were places that were getting replacement smart extruders, like every month and just they were just constantly shipping new ones.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, and then they they they fixed it by drilling a separate hole in it. Cause the main problem was that the filament enters and then basically there's like a 45 degree turn around a, encoder wheel and as you know Chris, there's a lot of filaments that are quite fragile. Yeah. You know, you can break them easily with your fingers and that's what was happening. As you go around the encoder wheel, the curve was too tight and they were they were cracking.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So what you do or what they did to fix it was actually drilled a different hole straight down that the filament could enter into, leaving the original entry point at the back like a useless prehensile tail.

Chris Kraft:So so I think but it'll be interesting to see if how well this goes because I've talked to, granted, there are people from competing companies, but I've talked to a couple people from competing companies that said their business just went crazy and it was all former MakerBot customers and they said the reason why their their business exploded was because all those people were sick of dealing with MakerBot printers that weren't functioning. So they were ready to buy anything that was more guaranteed to work. So is it too late, you know, for them, MakerBot, to get that business back? You know, I I don't know. Well, I mean, how

Benjamin Heckendorn:much cache does the name really have? I mean, if you think about like, you know, we all remember when the 3 d printing became hot, you know, what, 8 whole years ago? It wasn't that long ago really to think about it.

Chris Kraft:Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:And you know, for better or worse, MakerBot did lead the charge, you know, and there's no reason Joseph Prusak it's like it's like the difference between like a Wozniak and a Jobs, you know? Brie was Jobs and Pruso was Wozniak. Right? Well,

Chris Kraft:I would say even within MakerBot, there were people who you would say because there was 3 founders of MakerBot.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. That's right.

Chris Kraft:And the 2 that that are no were were essentially pushed out where your was is basically.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yep. And then all that was left was Bree.

Chris Kraft:Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. Oh, yeah. Because one of them's at Maker Gear now.

Chris Kraft:Is he? I didn't

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. One of the founders of MakerBot. Yeah. It was funny. He was we were we were talking about I think we're at this bar doing a flight and he was like, yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I remember I was back there at the very beginning when, like, we were like living we were staying in the same room and like sharing a mattress, we were so broke. With Bree, but then now, you know, one person cashes out and the other person's left behind. I guess that's business.

Parker Dillmann:So I I did a quick search on Kickstarter for 3 d printers and see if there is 3 d printers, like, having active campaigns and there are 3 right now.

Benjamin Heckendorn:That's it?

Parker Dillmann:A lot of them have been completed already and so they're probably not gonna get their stuff because that's just how it goes. But the best thing about it is all 3 of them have in their titles the most affordable blank. Yeah. So, like, the most affordable ceramic printer, the most affordable metal SLA, the most affordable 3 d printer ever.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Now, you should you should compare that to how many active wallet kickstarters there are right now.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, there's what, 80 of them?

Chris Kraft:Yes. And and my plead is for people to not buy printers off of Kickstarter, and unless they are something strange or experimental, but, generally, I say, if don't first thing, you can find them cheaper. You can find them cheap fairly cheap anywhere. Monoprice, whatever. But the other thing is, imagine you get a printer off of Kickstarter and it works perfect, let's say, for the 1st 6 months, and then a part breaks on it.

Chris Kraft:The kickstarter is over for all you know, the guy, he could be completely legitimate and still be gone, because Kickstarter is a point in time.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So you're you're saying that things could be just peachy, but you'd still be up a creek without a paddle?

Chris Kraft:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I would say, if you're if you're buying your first printer, I I personally go to Monoprice, buy something there. They've they've made 100 and thousands of those printers and so there's parts everywhere.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Didn't you update the firmware on yours recently, Parker?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I that was actually the first time I ever dabbled in the open sourceness of of the maker or the, 3 d printer community.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Don't most of them use Marlin anyway?

Parker Dillmann:Yes.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Okay.

Chris Kraft:Quite a few. I mean, there's other alternate there's other popular alternatives like Repiteer and, you know, there's there's a few others, but Marlin is the standout.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Parker, I mean, that's surely not the first microcontroller you flashed, so it shouldn't shouldn't have been that scary for you.

Parker Dillmann:No. No. That that part wasn't scary. It was the whole, like, downloading the source and and getting that to compile correctly and that kind of stuff. Because usually with open source projects, at least the ones I've used, they just go here's the source code and then you spend 4 days trying to get past compiler errors.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Oh, that reminds me that, yeah I remember about 3 years ago, 3 or 4 years ago when all of those like $500 MakerBot Replicator 1 clones started showing up on Ebay. Yeah. Before Monoprice. But there was one, I think Andrew got one and it had this dongle on it. The dongle was like a consumable.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Did I ever tell you about that? No. Oh it was so jinx. So it you know, you know, it's one of those $500 printers but this one okay. So you had to have a filament dongle, right?

Benjamin Heckendorn:So you buy you had to buy a roll of filament from them and it came with a USB dongle and you stuck it in the machine and then

Parker Dillmann:And this came from China?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yes, it was one of those $500 printers. But, so, we we took it apart and it wasn't even a USB device, the USB dongle was power, ground and then, I iS 2C to an ePROM which was basically just counting down until the dongle was inactive.

Parker Dillmann:And you could just write whatever number you wanted to it?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, we just reflashed it, using the AVR ISP mark 2 with Marlin because of course it was just to make a bot clone. But yeah, so basically it was well I was a it was, it was a Marlin firmware that they added basically an I squared c consumable dongle check to. DRM. So jank.

Chris Kraft:That's crazy.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yes.

Parker Dillmann:I wonder if if that company's still around. I doubt it.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Chris, remember the old days of having to wrap Nichrome wire around screws and then covering it with, like, putty?

Chris Kraft:I remember. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Is that to make your own heaters?

Chris Kraft:Mhmm. Yeah. Back in the day, we would take yep. Nichrome wire, wrap it around a barrel or like I think the first one I ever made, the first extruder I ever made, I used a TIG welding tip and then, yep, wrapped the nichrome wire around it and put some ceramic paste on it.

Benjamin Heckendorn:That was back when, Maker Gear they kinda got their start making the good extruder for the cupcake.

Chris Kraft:Right.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. Because it was a stepper because at the time, the cupcake was using a DC motor, but then Maker Gear was a stepper motor with a gearbox on it and it worked so much better.

Chris Kraft:Even before that, Maker Gear started because, at the time, the maker bought their extruder would jam up constantly, and then you'd have to try to clean it out, and you'd have all this ABS stuck in there, and you either could burn it out or, you know, soak it in acetone. But I wanted to have a spare in case because I actually broke one of my barrels trying to remove the the nozzle from it. And I contacted them. They're like, sorry. We have no spares.

Chris Kraft:We're not gonna have any spares until we finish shipping out, orders. And I don't know how, but I ended up getting in contact with Maker Gear, and he had he was making replacement parts, barrels, nozzles, and, insulators. So I bought the parts from him and put it on my printer. Same DC motor, same everything else, just new barrel extruder and, nozzle barrel and heat insulator. The second I put that on, I didn't have another jam after that.

Chris Kraft:So I was sold because he basically, his parts made my printer functional.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Awesome. Hey, what's this topic consymbol? I'm sorry. Consymbol. What's this topic consider the humble loofah?

Chris Kraft:Loofah, yeah. Oh, is

Benjamin Heckendorn:that that plant that looks like a sponge?

Parker Dillmann:It is a sponge.

Chris Kraft:I was thinking the other day about how different additive manufacturing is than traditional subtractive or even casting, where, like, forever, we've made things by grinding them or cutting them and getting them into the shape we want. But with Additive, it's you're basically growing the shape you want. And, I think that's really different. It's a different way of manufacturing, it's a different way of thinking about manufacturing, and as you get to lower and lower levels, you know, you're eventually just moving, you know, molecules around, or even atoms around. And, once you get to that point, like, all of manufacturing could radically change.

Chris Kraft:If a machine can literally just push molecules into positions, then, you know, the manufacturing will just be amazing. And then, it dawned on me that there is something like that right now, and that's the way nature works. Yeah. Everything biological, it grows out of raw materials, and, you know, there's molecular machines that are following DNA codes to construct whatever it is that it's growing, And, I mentioned the luffa because a lot of people own luffa sponges, and they don't even know where they come from. They just have a luffa sponge.

Chris Kraft:They think it's either made or they they literally just don't have any idea, and yet it comes from this thing that looks like a giant zucchini or something. And then they peel it apart and process it and pull out the the luffa sponge. And yet, when you look at the interior of a luffa sponge, it looks like the infill from a really fancy 3 d print, algorithm.

Parker Dillmann:You know, you know, we should have that as an infill option in your slicer.

Chris Kraft:LUFA? Yeah. LUFA. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:LUFA option.

Chris Kraft:You you could never well, I shouldn't say never, but trying to program a slicer to produce infill like that would be insane, and yet, I imagine within a loofa, it's just growing. It doesn't even have an algorithm, you know, it just happens.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, it's probably, you know, procedural in nature. There's like a base seed to it, pardon the pun. Yeah. And that dictates the manner in which it grows.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. Well, I mean if you

Benjamin Heckendorn:think about it Chris, all technology is basically reverse engineering of nature.

Chris Kraft:I I would agree except the way we've been doing it, like, with heavy manufacturing, you know, milli machines and and c and c's, that's not the way nature does things, and that's why I think this is interesting because if you imagine using a technology like CRISPR and let's say you reprogrammed, a watermelon's DNA, so that when it was done growing, you cracked it open and instead of being watermelon, it was, I don't know, liver or, you

Benjamin Heckendorn:know. We did already reprogram watermelon DNA. I mean watermelon is quite different than it was 100 of years ago. Like much like a dog, it's been bred into a different kind of kind of fruit.

Stephen Kraig:I I think, what what I I don't remember exactly what book it is, but Richard Dawkins has a a book where he dedicates an entire chapter to, cabbage. And the fact that cabbage as we know it just flat out did not exist. That is entirely like a genetically engineered vegetable that we created.

Benjamin Heckendorn:There's quite a few, of those like bananas

Parker Dillmann:Bananas would be watermelons. At all because it can't reproduce by itself right now.

Chris Kraft:Well, in in the banana, what was the most common banana was wiped out by, you know, a banana plague or something like that, and, that's how we ended up with the bananas we have now, although there's a new plague forming that they say if that hits, bananas might cease to exist completely. So

Benjamin Heckendorn:We'll have to 3 d print them.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. Get them while they're while you still can. Yeah. And, like, corn is another example of that's, you know, modern corn doesn't look at all like what corn looked like a 100 years ago, so but that's usually I mean, there's some genetic engineering, some of it is genetic engineering just by cross breeding, but

Parker Dillmann:Or selectively picking the plants and

Chris Kraft:Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. Or, like, you know, selecting dogs with short legs and a 1000 years later you have a corgi.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. Or crossbreeding corgis with huskies to make huskies with tiny legs, which sounds terrible, but Porgis? Husky or

Benjamin Heckendorn:Hoagies. I mean, really, if if you think about it, it's it's you have a species, humans, and they're smart enough to actually affect the evolution of the creatures around them. Yeah. Which is kinda weird. But if you think about it, it's still all part of nature because, you know, would you say, a beaver damming up a river is I mean it's a creature just like us.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. Well, and but imagine like if you could this, you know, like the luffa, which is a natural plant, but, like, imagine you had a zucchini that you cut open and it had tenderloin steak in it, because And

Parker Dillmann:it's already cooked.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. And then it's like, well, what do you say to someone who's vegan? You know, it's like, well, it's a plant, you know, it just produced meat.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I mean, if if you're talking about it that way, I mean, yeah, you we had the, subtractive manufacturing or cast manufacturing for 1000 of years. Now we have additive manufacturing, but what you're talking about is still, you know, several steps even beyond that. Organic manufacturing?

Chris Kraft:Yeah. What I'm saying is

Benjamin Heckendorn:At which point you'd basically become a god.

Chris Kraft:I don't know about that,

Benjamin Heckendorn:but Yes. You totally would be a god because you'd be creating things that that are life, that actually can like, you know, build themselves and sustain themselves.

Stephen Kraig:Wait. Okay. So like

Benjamin Heckendorn:So if you when you get pregnant, you don't have to sit there and 3 d print a baby, it just kinda pops out. Right. Every every every pregnant woman listening to this, oh, it just pops out. Right.

Stephen Kraig:So wait. Given given Chris' example of, I guess, the lever melon, the the the lever inside of the melon, we I guess there's life in that lever at that point or like a a craftsman wrench inside of a melon husk?

Chris Kraft:Well, yeah. I mean, like, if you can, if a plant can, if the if the biological material in a plant can move molecules around, then if you were to feed enough, say, iron into the nutrient bath for the plant, I don't know why it couldn't just move the molecules around, so, yeah, you cut it open and find a wrench.

Benjamin Heckendorn:I think I think there's randomness to that as well because you know, all of your luffa sponges aren't going to be identical. They're going to be different based off their environments and the light and the shade and like, you can see that with a house plant, like you can move it around and then it'll actually start moving toward the light source. So now, if you're trying to like create a wrench inside of that

Parker Dillmann:Well, you might get a 10 millimeter or you might get a half inch.

Chris Kraft:You don't know what Exactly. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So but that's it's an interesting way of thinking about it. I mean, I think before you even would need to do that, I I think, you know, as you were talking about just like, you know, additive manufacturing with molecular, manipulation is probably something that would happen before we're able to actually grow our own wrenches.

Parker Dillmann:So you're talking like building a Star Trek replicator then?

Chris Kraft:I guess so. I mean, I don't know exactly what the quote science behind a replicator is. But if it's a similar idea that they're using molecules, you know, or using something to be able to assemble something out of component. I guess that's my point is is that everything around us is is made by collections of molecules. So if you achieve the point where you could manufacture at that level, move molecules around, You could literally grow anything.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Right. But would it be growing? I mean, if you're, you know, if you have a machine that's moving molecules, that's different than growing because things that grow, grow themselves.

Chris Kraft:Right. Right. I meant when I meant grow, I meant additive manufacturing. That, you know, it would it would construct instead of being constructed by taking something and banging away at it, you'd it would grow in the sense that like when you watch a resin printer it's like the object seems to be growing out of it.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Right. So basically what you're talking about is additive manufacturing is at a much much much much much smaller scale. Yeah. Yeah. And I've Because if you think about it in a way, you talk about subtractive manufacturing, in the end, you're taking a 1.75 millimeter filament and you're mechanically basically making it smaller and squirting it out.

Benjamin Heckendorn:But,

Chris Kraft:yeah. I mean, did

Benjamin Heckendorn:they I mean, they can move, you know, they make molecular pictures already. That's already a thing. So it'll happen.

Stephen Kraig:And honestly, I think one of the areas that that really can shine in is the area of of, small electronics. Like, we're already at the point where the gate on a on a MOSFET is a 100 atoms across. So if if, if we could accurately place silicon or silicon dioxide atoms on top of, you know, a p n junction or or p n channels, We could we could theoretically get to what is, like, the best MOSFET using that technology, you know?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Until you get into quantum mechanics.

Stephen Kraig:Well, you're I mean, we're already fighting that as it stands. Right? But, like, there's there there we could find the optimal arrangement of atoms that is not grown in a heat chamber, you know, with gas

Chris Kraft:and stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Effectively, we put every atom where we want it to be, and and you basically say, given this materials, this is the best MOSFET that can be for whatever application.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. Because if you think about the way they make, why can't I think of the CPUs? It's, you know, they do it layer by layer and it's kind of like a photographic process still and that's where the limitation comes from. And then again, in the end, it's just like, oh, you know, materials are laying down where we want them to lay down. But, yeah, you're talking about discrete atomic control.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, yeah. Yeah. You start off with a a perfectly, I guess, I we're this is super idealistic, but you start with a perfectly flat silicon wafer, and then you build on top of that, or you etch out, you know, I guess chambers and you put Oh, no. No. No.

Stephen Kraig:You can't etch. That's subtracting. Okay. Okay. So yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I guess I guess we start from

Benjamin Heckendorn:the very bottom. You you wouldn't need to do that because if you can if you can arrange molecules, you know, they like they stick together like little ball bearings. Right. In the corners, you know, you could make, well, near perfect walls, you know, they wouldn't be straight because they're they're molecules, I'm sorry, not atoms. Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:That'd be pretty cool. I mean, I I'm sure we'll get there at some point. It just takes a it takes

Stephen Kraig:a little bit of time. Chemical processes work a little bit faster than moving individual atoms.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Right. And then as we've all seen like Moore's law is totally done and I think that's why is because we're pushing the limits of, because you know we're technically still making you know, CPUs the same way we were decades ago just at much higher precision.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. The other thing that would be interesting is the the product that you could produce would be limited by the source materials and the plans, you know, the model. But one machine, in theory, could, you know, create a wrench, and then the next run, it could create a chip. As long as you fed the right kind of goop into it, so that it had the right kind of particles to move around. Once it can move once it can move atoms around, it doesn't matter if it's moving those atoms around to create a liver, or if it's moving those atoms around to create, you know, a wrench or a integrated circuit or anything.

Parker Dillmann:So I've got a really good trademark term for that goop. God goop.

Chris Kraft:God goop?

Parker Dillmann:God goop t m.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Well, wouldn't you have to have some sort of hopper that has a bunch of atoms of different elements?

Stephen Kraig:You just have every element. Right?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. It's just a just

Parker Dillmann:a slurry of just all the atoms.

Stephen Kraig:It's just a hopper that looks like the periodic table. Yeah.

Chris Kraft:Yeah. And if you made a lot of if you made a lot of a particular thing, then it would be like the stupid printer ink, where your black is out, but your magenta for some reason is fine.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yep. Yep.

Chris Kraft:So, you know, one guy's titanium cartridge would be empty and, you know, his, neon one would be full and he'd be swearing at us because we're charging him, you know, a $1,000,000 for a new printer cartridge.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So what actually causes, 2 atoms of titanium to stick together to be a piece of solid titanium?

Chris Kraft:Well, it's it's one of 4 known forces. The electro, it's the strong force, the weak force, gravity, and Electromagnetic, right? Electromagnetic. Yeah.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So they would be electromagnetically connected because they're atoms with electrons.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. That's right. That's right. They're okay. Because they they form bonds.

Stephen Kraig:Could I'm not entirely sure specifically that material, but it would just be an electromagnetic bond between the 2. Right? I would probably stepping out into territory that we're all not exactly

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Chris Kraft:Tested. But I think it's all forces acting because, like, the strong and weak forces are important too in that scenario because that also affects how, atoms are bound together. But you're right. We're way out of our

Stephen Kraig:Well, now you're really talking about playing God.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I know if I know if you have, like, 2 really flat pieces of of similar metal, like, let's say, 2 pieces of steel and they're very let's say they're perfectly flat and you stuck them together they were actually cold weld together. Mean, that's actually how they put together pieces, like, in outer space sometimes is they've been experimenting with this cold welding kind of stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Well, you could do that with gauge blocks. That's sort of one of the tests of a good gauge block. You ring them together and they stick.

Parker Dillmann:Bringing them together. So whatever that force is is what keeps most things together, I think.

Benjamin Heckendorn:And, you know, I think if you got to that scale, Chris, you would need some sort of procedure generation as well because think about how much data it would take to store all those atoms as attributes in a device list.

Stephen Kraig:An x y location for each one or x y z?

Chris Kraft:And that's why that's why I go back to, like, the luffa because or trees or, you know, you look at the roots of a tree, you look at the branches of a tree and you see patterns. You know, some people call it the thumb of God, but it's like, it's a fractal mathematics that can define those those complicated structures.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Right. So like let's say we're living in a simulated universe and my monitor stand which is made of wood is fake. Right? Now, you wouldn't program in all of the atoms to represent the inside of that unless I was to cut it in half. Right?

Benjamin Heckendorn:So you either have a repeating pattern like a texture in a video game or a procedurally generated pattern and then a define of the outside of it. You know, you only define what is absolutely necessary to define the object and that's where you get into fractals, the way things grow, repeating patterns and loofah sponges. Yeah. Yeah. It seems like one of those things like, you know, you would actually you'd create an atomic printer and then the things you learn along the way about it, you'd be like, oh, we are living in a simulated universe.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Right? Or there there is a God, you know, you would actually learn you'd actually figure that out in the process of doing this, you know, because if you're talking about like atomic manipulation like maybe the trick is just to hack the code of a simulated universe.

Chris Kraft:I don't know. I think if we're living in a simulated universe then coders need to be fired because it's really buggy.

Parker Dillmann:Is there is there a, support ticket system that we can put some tickets in?

Stephen Kraig:Thoughts and prayers.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Thoughts and prayers. Your call will be answered in the order it was received.

Chris Kraft:No. They all get reply they all get responded with, you know, not an issue working as designed. It's a feature.

Benjamin Heckendorn:Not a bug. Nice. It's like, oh, my god. Why does water expand when it gets cold instead of contract? Screw it.

Parker Dillmann:So Not a polar polar molecules is a a bug in the system?

Benjamin Heckendorn:Yeah. It's like Bethesda designed the universe. Earth 76. Hey, wait. Chris is one of the 5 people who like that game, so we get we can't trigger him.

Chris Kraft:Oh, no. I under it's a deeply flawed game, but I still enjoy playing with my friends.

Benjamin Heckendorn:So any other closing topics regarding 3 d printers?

Parker Dillmann:I don't think so. We've been, rambling pretty good for the past hour. So if y'all want to sign us out.

Chris Kraft:Okay.

Benjamin Heckendorn:That was the MacroFab Engineering podcast. I was your guest, Benjamin Heckendorf.

Chris Kraft:And I was another guest, Chris Graf.

Parker Dillmann:And we are your hosts, Parker Dillman. And Steven Craig. See you later, guys.

Stephen Kraig:Take it easy.

Parker Dillmann:Thank you, yes, you are listener, for downloading our show. If you have a cool idea, project, topic, or a loofah that you want Steven and I to know about, tweet us at macfab@longhornengineer with no o's, or at analogengoremail us at podcast@macfab.com. Also, check out our Slack channel. If you're not subscribed to the podcast yet, click that subscribe button. That way, you get the latest MIP episode right when it releases, and please review us wherever you listen as it helps the show stay visible and helps new listeners find us.