- Introduction to HMLV: What does High Mix Low Volume mean?

- Differences between HMLV and high volume manufacturing.

- Flexibility and specialized equipment required for HMLV.

- The importance of a skilled workforce in HMLV environments.

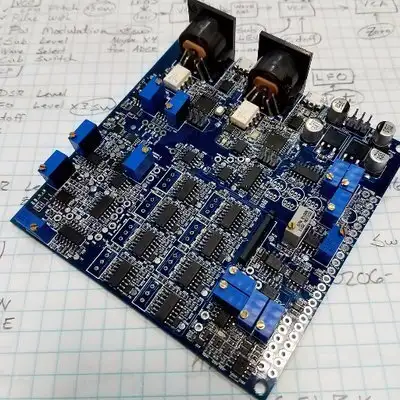

- Personal project updates: Cyclone Pulse Wrangler and LED Matrix driving.

- The significance of proper inventory management in HMLV.

- Insights into MacroFab’s platform updates and their new glossary of electronics terms.

- Real-world examples of companies utilizing HMLV in their manufacturing processes.

- The role of HMLV in prototyping and early design cycles.

- Discussion on the transition points between low volume and high volume production.

- Challenges faced with parts handling in HMLV.

- The necessity of adaptability in both workforce and equipment for HMLV.

- Parker’s PWM fan controller circuit review and schematic discussion.

- The impact of battery voltage on digital inputs in automotive systems.

- Analog inputs and thermistor readings for temperature measurements.

- Push-pull current drivers and the need for logic gates to prevent run-through situations.

- What are your thoughts on HMLV manufacturing? Have you encountered any specific challenges or advantages in your projects?

- How do you manage inventory in a high mix low volume production environment?

- What strategies do you use to transition from low volume prototyping to higher volume manufacturing?

- Have you implemented any interesting circuits or solutions in your personal projects? Share your experiences!

Creators and Guests

What is Circuit Break - A MacroFab Podcast?

Dive into the electrifying world of electrical engineering with Circuit Break, a MacroFab podcast hosted by Parker Dillmann and Stephen Kraig. This dynamic duo, armed with practical experience and a palpable passion for tech, explores the latest innovations, industry news, and practical challenges in the field. From DIY project hurdles to deep dives with industry experts, Parker and Stephen's real-world insights provide an engaging learning experience that bridges theory and practice for engineers at any stage of their career.

Whether you're a student eager to grasp what the job market seeks, or an engineer keen to stay ahead in the fast-paced tech world, Circuit Break is your go-to. The hosts, alongside a vibrant community of engineers, makers, and leaders, dissect product evolutions, demystify the journey of tech from lab to market, and reverse engineer the processes behind groundbreaking advancements. Their candid discussions not only enlighten but also inspire listeners to explore the limitless possibilities within electrical engineering.

Presented by MacroFab, a leader in electronics manufacturing services, Circuit Break connects listeners directly to the forefront of PCB design, assembly, and innovation. MacroFab's platform exemplifies the seamless integration of design and manufacturing, catering to a broad audience from hobbyists to professionals.

About the hosts: Parker, an expert in Embedded System Design and DSP, and Stephen, an aficionado of audio electronics and brewing tech, bring a wealth of knowledge and a unique perspective to the show. Their backgrounds in engineering and hands-on projects make each episode a blend of expertise, enthusiasm, and practical advice.

Join the conversation and community at our online engineering forum, where we delve deeper into each episode's content, gather your feedback, and explore the topics you're curious about. Subscribe to Circuit Break on your favorite podcast platform and become part of our journey through the fascinating world of electrical engineering.

Welcome to circuit break from MacroFab, a weekly podcast about all things engineering, DIY projects, manufacturing, industry news and HMLV. We're your hosts, electrical engineers Parker Dillmann. And Stephen Kraig. This is episode 440. So HMLV Stephen.

Stephen Kraig:What does that mean

Parker Dillmann:to you Parker? Well, I would actually really wish I came up with a really funny acronym for it, But it actually just means high mix low volume PCB manufacturing.

Stephen Kraig:Which is so thrilling and exhilarating.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Thrilling and exhilarating.

Stephen Kraig:Actually, it is totally because that's what I do on a daily basis. So I actually really like it.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. And that's that's what Maccab started as as well. Remember back in the day?

Stephen Kraig:Absolutely. Well, Maccab started as it, but also you that's still your bread and butter in a lot of ways.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That's that's still what we do a lot at, our HQ facility for sure. So what high mix low volume is is basically instead of, it's it's basically the exact opposite of, like, what Apple does or what Foxconn does, where you're setting up a line that will build one thing.

Stephen Kraig:And is really, really good at doing that one thing.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Very good at that one thing where, the main thing with high mix low volume is mostly being able to handle really high mix of components. That's what the high mix part is. I guess you can also say, like, high mix of products, but I always viewed as just like the component level is handling lots of different SKUs of components, a lot of different line items. And then low volume, meaning you're building you know what?

Parker Dillmann:What is low volume to you? And you

Stephen Kraig:know what's funny? I was literally about to ask you that same question because low volume to me has kind of shifted a little bit, because back in Macrofab, some of the higher volume runs when I was working there were in the higher 100, like 7, 8, 900 kind of thing. Whenever I was working at WMD, my my previous job, high volume for us represented, like, 4 to 600 and high volume where I'm at now is, like, above 10. So so it kinda shifts. It it just depends on on what what your requirements are.

Stephen Kraig:But in general, I would I would probably say, like, across the board, let's say, 500 and above is high volume, and then 100 to 500 is medium volume and anything under a 100 is low volume.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. High volume or low volume to me is I guess I look at more like on the component level and if you have to use more than a reel of a certain component that starts getting to I consider that past low volume status.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. Yeah. I could I could see that.

Parker Dillmann:So if you have like a board that has 10,000 resistors on it, and you need you're building 2 of them. That's and that that gets kind of weird, but that's how I start viewing it as so I I most time that cutoff though is funny enough around 750 units. That's when that starts to play into you now need to have multiple trays or multiple reels of a component.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. That's an interesting way of putting it because you're basing it off of components and not units, not finished goods. So, actually, one one other way of saying that is if the kit of parts has to ever be refilled, then it leaves low volume for you.

Parker Dillmann:And that's for me personally. Yeah. Okay. Okay. Because I don't, like, the Macrofab platform itself doesn't have this concept of high volume low volume.

Parker Dillmann:It used to back in the day, like, I'm back in 2017 era. It had, like, a low volume button and a high volume button in the platform.

Stephen Kraig:Well and and you guys are way more of a spectrum when it comes to ordering, your quantities. And and if correct me if I'm wrong, but the platform will recommend different manufacturing options based off of your where you fit in companies.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So act actually, Donald, since we're bringing up the platform, it's when so the platform has this really cool graph where, it will show you, like, your quantity and the price breaks over, like, every unit you add on, it will just calculate the price out for you and just draw draw you a graph. It's when it's when you know what? I should come up with, like, an actual, like, number for it because when the rate of change on the graph levels out, it's like when the hockey stick levels out

Stephen Kraig:Plateaus.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah, plateaus, but still it always slightly goes down usually. So there's a rate of change, there's a derivative of that graph when it hits under that number sure that's high volume

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. But but but it is there's never, like, a exact defined point where it just levels out. It it it it just it tails off.

Parker Dillmann:It tails off. It takes

Stephen Kraig:a long time to get there. In other words, there's not like this really, really sharp point where you go, that's the best manufacturing point. That's my quantity right there.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. That is true because it's the more you build all what you always get price breaks or it always because basically what happens is you end up ordering when you get big enough on you end up ordering directly from the manufacturer, so you don't go through the distributor and you get a price break there, but you have to buy like boxes and boxes of stuff from them.

Stephen Kraig:You you know, actually, that that that point we're talking about where it might make a more sharp transition, that's when you really start to ask the question, do I just buy my own manufacturing facility to build my one thing? My volume is high enough that I could it might make sense to hire a whole team, make an entire assembly line and build my own thing.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, that's way out there.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. That's like yeah. That's like you don't see that part on the ground.

Parker Dillmann:I mean, even even Apple doesn't even do that anymore.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Nintendo doesn't do that. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:They just go to Foxconn or whatever. Right. I the only time you really do that is when you have really specialized stuff. Right.

Stephen Kraig:Or or if you just have to have control in house.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. When when increasing so I guess I'll rephrase that high the break between low volume and high volume for me is when increasing volume of units doesn't significantly change the price per unit anymore.

Stephen Kraig:Mhmm. K.

Parker Dillmann:So there's that there's that point where, like, the the the graph kicks flat, or flattish, and that's where that point is where I would consider low volume, high volume, because, and price and quantity. And funny enough, that is around 600 to, like, 800 units for most boards. It's true. In that area,

Stephen Kraig:which which falls in line with what I was saying earlier when when I was working at the fab. Those were kind of the the bigger runs. I mean, there were runs even bigger than that, but but those were, like, the bulk of what we would call high volume.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's really funny now, where we have, like, actual high volume stuff now, and it's, like, you know, people ordering boards and then getting board shipped weekly for years.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. That actually I would I would not even call that high volume anymore. I would just call that continuous manufacturing.

Parker Dillmann:It is continuous manufacturing like Yeah. Oh, is this true? So a long time ago, I was reading up on different brewery brewery strat. I know what time it's High Vex low volume. I know what time with that, but but breweries, I think so this is a story I heard about Budweiser, and they have a continuous stream of beer in their plants for Budweiser beer.

Parker Dillmann:Maybe it's for Bud Light. We're, like, the flow doesn't stop in batches, like it does for most breweries.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Well, correct. There is a Everything is batch when it comes to brewing. However, there I'm trying to look it up right now. There there's a gentleman a long time ago that patented a process of continuous brewing where the output of fluid is met by incoming fluid and the yeast continuously produces alcoholic beverage and you just maintain those input outputs and it just never stops fermenting.

Stephen Kraig:And so it's not a batch, It is just a continuous process. I don't I'm I'm failing to find it right now. Okay.

Parker Dillmann:So this I didn't make that up.

Stephen Kraig:You didn't make that up. I don't think the major players use utilize that process.

Parker Dillmann:Okay. So I I was wrong with that then. Which is fine. I'm always wrong.

Stephen Kraig:Sorry. I'm not trying to just tell you you're wrong.

Parker Dillmann:So alright. Back to high mix low volume. So, yeah, that's that's what low volume to me is in that that range. And but what does that mean for, like, for, like, you as an engineer then? Like, when when if you're out there looking to go buy, boards, like, get your PCBs assembled, Do people actually search for high mix low volume?

Parker Dillmann:Is that something people actually search for?

Stephen Kraig:I don't think I've ever specifically searched for that. Although, I I will tell you I have searched for contract manufacturers and just with a few glances at a website, I can tell that that manufacturer is not right for me. Because depending on how their their website is set up, it it will tell you a bit about that that Centimeters and maybe that's this sounds a little bit unfair to just immediately write something off. But I don't I'm not gonna go to Foxconn and say, can you make 2 boards for me? And if you go to the Foxconn website or or or or bigger websites like that, you just know this is large high volume manufacturing.

Stephen Kraig:And if I need a small run of cheap boards, they're just gonna tell me to pound sand.

Parker Dillmann:But you've never been to Foxconn's website.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. There's there's there's certain manufacturers that you could just tell that that's the case, and, they're looking for the really big orders.

Parker Dillmann:So if you go to foxcon.com, It actually doesn't say what they actually do on the front page. The first thing you see is technology for smart living and then creation of a better future together and then the next tab is ESG sustainable developments. So I don't say anything about actually building boards and products through today.

Stephen Kraig:So does that scream, yeah, we'll make 2 boards for you, for $200. Not really. Right?

Parker Dillmann:They have something called 3 +3 equals infinity. What is that?

Stephen Kraig:If they're doing that kind of math, then, I can't afford them.

Parker Dillmann:Apparently, that's an event that they have. 3 +3equalsinfinityevent. Oh, well. Not talking about Foxconn. But you're right.

Parker Dillmann:You're right.

Stephen Kraig:But that's that's an example of, but but what what you were saying was actually kind of the opposite. Like do you go find a Centimeters that's like we do the the low volume stuff. And you know what's funny? The only one that I'm really aware of is MacroFab, that that says, like, yeah, like, we welcome this. Don't get me wrong, I've talked to plenty of CMs who are like, yeah, absolutely we'll do that, but but MacroFab screams it a lot more or at least being able to support it, I should say.

Stephen Kraig:Because it's not necessarily MacroFab's goal to just do the the low the the, high mix, low volume stuff.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That's that's what I'm just getting at is, I talked about this before I switched to marketing full time this year, at the beginning of the year and that that's one thing I'm like trying to figure out. I'm like, what are engineers actually searching for to go find things? Like, find cms? Like, how do I market macro fab and find out, like, you know, if someone's searching to get their their 50 let's say 500 units made of something, like how do they even go about finding a Centimeters for that?

Parker Dillmann:And, I don't know. Are are they searching HMLV? Is that, like, that's not a that's not even a term that is taught at all in college. Right. So I don't is that even a term people have been searching for?

Parker Dillmann:Or is it something more of like an educational topic on where, like, you land on a site and you just happen to see high mix, low volume being on the sites?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I I I think it it comes up in conversation when you reach out to the Centimeters and you say, what are your capabilities? Here's what I'm expecting. And they just come back and be, like, yeah, that fits really well within our process or no, that's terrible. Sorry.

Stephen Kraig:Go away.

Parker Dillmann:I guess so. Yeah. I'm just trying to think of how do I, would market a high mix low volume terminology. Mhmm. I guess putting it maybe it doesn't, like, you don't advertise HMLV because no one's searching for that.

Parker Dillmann:Right? So it'd be really cheap it would be really cheap to keyword that because no one's actually searching for it.

Stephen Kraig:But it wouldn't get you very far.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. But having it where getting across to the person who lands on your website that you welcome high mix low volume without actually saying high mix low volume because the if you just say HMLV, I bet you actually most people won't even know what that is if the engineers landing on the site will see what that means. So if you say we do high mix, low volume as part of your marketing spiel to get someone to click in, that might be a better use of it.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Actually, I think I think one way that might work is showing or or demonstrating somehow how you fit in the design cycle for an engineering team. So in other words, at the beginning of a project, there's there's a lot of churn, there's a lot of, new ideas, there's a lot of design work happening, there's mistakes being made, That's your high mix low volume portion when you're doing your first prototypes. Like, nobody's expecting that first prototype to be the the final thing that you build. So you're building low quantities, you're building a handful of prototypes, you might go through multiple cycles.

Stephen Kraig:Then once you feel more confident in your design, you're going and building a production preparation run. So maybe that's 50 units, maybe that's a 100 units prepping for what is actual manufacturing, and then beyond that, you have the next run which is game day and that's your actual flight run where you're building, you know, a few thousands of things Demonstrating that you can support all 3 of those is in a way showing HMLV. Just HMLV is the very beginning of that process.

Parker Dillmann:And what's really interesting is we were talking about actually, like, hardcore number units like, 6 100, 800 for this. I've I've been talking to some of our customers. So what they do is they order their, like, core hardware team will order 10. Yeah. Okay.

Parker Dillmann:They order 10 units. And then when they get those boards and the hardware team validates it, they place another identical run before a 1,000 and it's still they consider that prototyping because that goes to all their teams all over the world Okay. For firmware development.

Stephen Kraig:The okay. Wow. A thousand.

Parker Dillmann:So a thousand units is like Yeah. That's just that's just part of development.

Stephen Kraig:Right. I guess it just depends on

Parker Dillmann:the size of the company. Yeah. It depends on the size of the company and what product it is, but then, like, because they've done, like, 3 of those so far. Wow. And I don't know if it's that's exact number I know they've done a couple but so it's like yeah and then so they do a revision they get 10 the hardware team validates everything is good and then they build a 1,000 more and that's that's that's for someone like you and me, that's insane of a prototyping cycle.

Parker Dillmann:Yes.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. That is. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:That must be the extreme.

Stephen Kraig:But

Parker Dillmann:that's that's so it's crazy to think about that. If your project is big enough has enough people work on it. It's right though. Like if if if you need, hardware in the hands of whoever's working on the firmware, and you got a big team, you know. Thousand.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Thousand. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:That's a lot. Yep. But but but so it just depends on, I guess, two things. It depends on the size of your company and it depends on what your design cycles look like. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:And that kind of gets you out of the high mix low volume into the higher volume production. But then again, maybe not because your product like, I'll take my job for example right now. We we do space stuff. It's we're not sending thousands of them up there. Highlight high volume for me is is tens right now.

Parker Dillmann:The only only person that does space like that is SpaceX with their satellites, their their Starlink stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. And even then and even then it's not, like, a huge portion of their company.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. How many Starlinks are in orbit?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, I looked that up a while ago. It's a lot.

Parker Dillmann:How much in their constellation? 6,219 which that's a lot of satellites. That's not high volume though.

Stephen Kraig:That's 6 prototype runs for this company you were talking about.

Parker Dillmann:Not 6 prototypes for this one company. Yeah. Alright. Alright. Let's switch gears on high mix low volume then.

Parker Dillmann:Sure. What because you because you worked at WMD and I've been working at MacFab for a long time. What do you what's the difference between a Centimeters that can do high mix low volume and one that can't? You were talking about the ones that will just say, you know, buzz off if you're trying to do something like this.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Okay. So in my experience, typically, what that means is they have manufacturing lines that are very very focused. I'm I'm talking about companies that will tell you, sorry, go away. It they have they have machines that are specific for high volume and they have workforces that are specific for high volume.

Stephen Kraig:And, and and typically, that's what drives them away from the low volume stuff. That's And that's like wave soldering and and and things of that sort.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Because we've done some tours. This is back when you were at the fab. We did tours down, some facilities down in Mexico, and those are definitely very specialized facilities because they made the ones that we were looking at, working with, they were doing TVs. Mhmm.

Parker Dillmann:And those were highly specialized equipments. The built

Stephen Kraig:in They had multiple lines, but they were all identical. They had their workforce was trained specifically on a single product and the intent was they could bring that workforce in, they knew exactly what they needed to do, there was no they they had supervisors and and whatnot going around, but it it it just it was intended for one thing over and over and over. And it was the I think one of the big things is it's actually a huge amount of work to get that kind of a labor force to do something else, because it takes so much training, because it takes so much setup, because it takes so much extra effort. In fact, one of the facilities we visited, they we got to see their testing facility. I mean, they had they had rows upon rows of people with identical testing, rigs that, that were all, like, hyper focused on a singular product.

Stephen Kraig:And and even I remember walking through the the storage they had of the TVs, the storage facility And and what it reminded me was, in Indiana Jones when they when they put the Ark of the Covenant in the box and there's just, like, the there's just boxes upon boxes of relics in that one facility. And, like, it looked exactly like that, but they were all the same TV.

Parker Dillmann:I I think it's the that's the biggest difference is is the flexibility. Because at, MacFab at our HQ facility, we run my chronic picking places, and the reason why we went because, but actually before then we had a universal GSM, which is the exact opposite of that that machine. That's a high volume machine. Yes. And so basically the main difference between those those kinds of machines are how many feeders does the head have access to to pick in place.

Parker Dillmann:So, like, a high volume machine might have multiple heads, but it can only hit like, let's say 32 feeders. Mhmm. Like, actually, there's a lot more crossover, like the more modern machines have a lot more crossover, in what they can do, like, high mix and low volume. But, like, a Micronic is I think it has something like a 128 feeders its head has access to. And it's got different different formatting for how the head picks stuff up.

Parker Dillmann:So you have, like, one head that might have 6 nozzles on it or something like that instead of a dual gantry machine. Kind of same thing with those, like, those turret style chip shooters, which is a very specialized equipment that's literally designed to only place one type of components. So if you need to switch that machine over, you gotta switch all those nozzles manually, but it can place that 10 k resistor perfect at lightning speed. Right.

Stephen Kraig:I've also noticed if you if you look at an assembly line and they have multiple pick and place machines in line with each other, that's usually an indicator they're not low volume. Because they'll have one one of the machines set up for all, like, the the the popcorn parts, like, all your r's and c's and things. And then the other one is typically set up for your big parts like your your ICs and connectors and things of that sort.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So actually, we'll roll back just a little bit more on like when you start considering the low volume to high volume. When you got to go wave if you have through hole parts, it's when you have to go wave solder. Yes.

Stephen Kraig:Yep. Yep.

Parker Dillmann:That's kind of the break point I think too. Because one, you have to get specialized tooling. Even though the tooling is not that bad anymore. Back in the day, getting a wave solder pallet was, like, 1,000 and 1,000 of dollars Yeah. And months of time.

Parker Dillmann:Now you can get one for a couple $100 and, you know, 2 weeks of work. Yeah. To

Stephen Kraig:get get there. They're not terrible.

Parker Dillmann:They're not terrible anymore. I think it's just But this is

Stephen Kraig:Actually, you know, that right there, if if any of your manufacturing requires additional fixtures or or jigs just for the manufacturing part, not for the testing part, but just for the manufacturing part, that's a good indicator you're in the high volume world. Right? Yeah. Because because that's the whole thing about, contract manufacturing with low volume stuff is everything is so well defined in terms of all the machines for the express purpose of being quick with high volume churn and, or sorry, high mix churn. And and and so as soon as you need things like wave pallets or fixtures for holding things in whatever machine or whatnot, the the only time you're willing to spend that kind of money is if you're already ready to go for high volume stuff.

Parker Dillmann:Mhmm. Yeah. And, but that also leads into you're talking about the workforce. That that's also a big indicator is if a shop that's high mix, low volume, capable, their workforce is gonna be a lot more flexible because they have to be. They see, like, let's give an example of that TV factory.

Parker Dillmann:They are building 1 SKU TV. Yeah. Okay. So if you were like, okay, let's now build a microwave. Just this is an example.

Parker Dillmann:They would probably have to retrain everyone.

Stephen Kraig:Yes. Exactly.

Parker Dillmann:Whereas at at MacFab, we don't build TVs or build microwaves, but for the example would be our our workforce only needs, like, a document to explain how it goes together. They're how much more highly skilled, line workers and assemblers, where they can read documentation themselves. They don't need to be fully trained up every single time you need to tear a line down. They're much more flexible. So that that's that's where the skills that's that's the skill gap between those two systems either, as well.

Stephen Kraig:And and that's not necessarily to just say that someone in a in a large volume is unskilled. It's just that their skills are in maintaining time as opposed to changing jobs and being able to be flexible.

Parker Dillmann:100%. Yeah. Didn't mean it as a dig or anything like that at all.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Right. Right.

Parker Dillmann:No. It's totally just a different skill set. One is just making sure a task gets repeated correctly with utmost precision and on time Over

Stephen Kraig:and over and over.

Parker Dillmann:Over and over again. And the other one is making sure that you're enacting precision on changeovers, and your changeover might be 4 or 5 times a day. Right. And so you and you have more time just in the nature of the work to do that changeover. Get getting a a

Stephen Kraig:large facility with multiple lines, getting that machine to turn over into something else is measured in months, not in days. Let alone, like you said, somebody switching jobs multiple times in a single day.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I mean, it's hard for me to do and I don't even do that work anymore.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. It it does. Both of them require special workforces, that are just they're trained and they're good at that. Actually, you know what's funny is it's it's kind of hard to even switch those 2 workforces, for for those to wear the others hat.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, that's why you you hire specifically for those positions like for high volume or high mix. And both are valuable in their own way.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Now I don't have anything else to add to to high mix low volume.

Stephen Kraig:You know, the only thing I have to say is high mix low volume comes with some really interesting challenges with parts handling. That's something that I think is worth noting because your inventory management becomes really critical for that. Because most of the time when you talk about your high mix stuff, you're not you're not providing boxes upon boxes of the same part for for them to deal with. And most of the time with high mix stuff, it's in and out of the shop as soon as possible because that's what the customer wants and that's also what the Centimeters wants because they get the job done and they get paid for it. But that comes with challenges because the same amount of care needs to be applied to the parts and inventory as the high volume stuff.

Parker Dillmann:I I would say that is probably the biggest benefit at working working with Mac Crab is our inventory system. Yeah. It's a class 1, class a feature set, I guess, in our platform. It's so funny when you like because when you look at our platform and you like, most users won't even touch the inventory side. But how all that works on our back end is like top of line.

Parker Dillmann:It's it's not like we took an another ERP system or whatever, like a normal Centimeters.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, it's homegrown.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. On our end, all our entire inventory system's homegrown and fully integrated into our platform. So it's it's funny. It's it's super specialized in doing high mix low volume handling the components. So Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That's a good point about about inventory. Yeah. Because that's in my opinion, that's the most important thing for a contract manufacturer is and number 2 is making sure you're is making sure the boards are good. That's, you know, what you actually deliver.

Parker Dillmann:Right?

Stephen Kraig:Well, I think I think yeah. I think inventory can make and break make or break things.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, it does for sure. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And it can also leave a really bad taste in people's mouth or the the client's mouth. So, just showing that you care about the clients, not just their money, but their their their their stuff.

Parker Dillmann:Their stuff. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:That that that really goes far. Alright. So we we we talked about

Parker Dillmann:high mix low volume. I do have some macro fab updates. Yeah. None of them actually have to deal with high mix low volume.

Stephen Kraig:Okay.

Parker Dillmann:1, this is what I've been working on in marketing for the past, like, 2 weeks. I I went through our blog and pulled all the old platform updates and then all the new ones. This this actually stemmed from, like, our product team here wants to, like, market our platform changes better. Mhmm. And so we came up with an idea basically, and when whenever they have an update, we make a blog post and we actually made, its own, like, landing page that the blog hooks into, with its own tag and stuff, which I know it was, like, that sounds really boring and, like, yeah, that's blogs at Macrofab.

Parker Dillmann:Right? And, so, yeah, I organized everything. So you can go to I think it's macfed.com/platformhyphen updates and so you can see all our new features customer facing features. Unfortunately, I haven't been able to convince the product team to let me release, like, what they do on the back end for macro fab. I love to show that stuff too, but so far I haven't convinced them yet.

Stephen Kraig:Keep working on it.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. But I have all the customer facing stuff there, and I got all the old stuff from back in the day. It's really fun going down memory lane of, like, back in 2013 13 and, like, rereading the blogs that, like, Chris, Church and I wrote back then about the product. And there's, like, old screenshots in there and a lot of those old blog posts were, like, copy pasted, like, 4 or 5 times through different, like, blog hosts and stuff and so I had, like, spruce them up a little bit. I, like, put, you know, make stuff bold and put headers on stuff and, like, fix captions or, like, images were broken, so I fixed the images.

Parker Dillmann:So yeah, it was a lot of fun, making the project work. I'm pretty happy with it. I I don't know if that will sell us more boards, but at least now like we have a proper place for, you know, product updates.

Stephen Kraig:It's in one place.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's all in one place now And and reading those old blog posts, it's it's almost like, how did people give us money back then?

Stephen Kraig:There's always the early adopters. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's because a lot of the it's very interesting. I I highly recommend everyone's listening, like, just go read some of these old ones that we wrote because that's very, like, our vision was so grand. Oh, yeah. I love I love reading it.

Parker Dillmann:It reminds you it reminds you of why you started it back in the day. Like, what was going through our brain back then? So Right. Although, I kept kept actually, all those old blog posts that, like, engineering stuff that you and I wrote back then are also up there, but it's really hard to find. So part of my next initiative is to work on that and make, like, all those engineering articles easy to find, all the technical stuff that we wrote.

Parker Dillmann:I wanna make all that really easy. Same thing with like the news, we have a lot of old news, Macfab news stuff that is just hard to find and I'm just gonna make it easy to find. So again, I don't know if that's gonna sell more product, but

Stephen Kraig:it makes me feel warm and fuzzy. I I still occasionally run into articles that you and I wrote.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That happens all the time.

Stephen Kraig:We put, like, on Google. Just, like, oh, okay.

Parker Dillmann:I recognize that. My my favorite is when I'm googling something, and I always put like, oh, I've I always put because you see back in the day, you type something in Google, and then you'd be like search images and then there would be a discussion tab. Mhmm. And discussion tab in Google, it would just show, like, forms and stuff. People talking about that stuff, and they got rid of it for a long for a long time.

Parker Dillmann:They actually just brought it back. Did they really? Yeah, so I think it's called let me check. I think it is called if you click more. No.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, it's called forms. So it's images, shopping, videos, news, forms. So they basically brought back discussion as a tab. Okay. Well, because I what I was doing for a while was I mean, for I can say for a while, for, like, the last 8 years is I type in something and then just put in form after it, and it would filter only forms.

Parker Dillmann:But now they added that as an official thing again, which is nice. When I find I'm searching for something, click on a form link, and they're referencing something that me or you wrote.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. That's cool.

Parker Dillmann:And that happens not often, but it's it happens more often than I would assume, given how the fast the Internet is.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's kind of scary that that people are referencing stuff that we wrote.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. But a lot of the stuff we wrote doesn't change.

Parker Dillmann:That that is true. It doesn't change, and at least it was correct enough that no one corrected us. True. So we know so at least it's correct enough. Is that going to be the title of this episode?

Parker Dillmann:Correct enough. Or, what did I say before that?

Stephen Kraig:You know, actually, it's funny because before the podcast, we were talking about, a handful of things. And one of the things that came up was the topic of like good enough engineering. I I feel like we have there's some really cool episodes that are coming around the corner here with some really cool guests where we're gonna be discussing this kind of stuff. I I I'm feeling a trend show up here. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Exactly. Good enough engineering.

Parker Dillmann:Yep. Exactly. So yeah. The platform updates, go check those out and then we just launched a glossary on electronics and PCBA terms.

Stephen Kraig:This is actually really impressive.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So it's maccab.com/glossary. Go check that out. I put in an error somewhere, so go find it.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, you purposefully put in an error. Yeah. Is there a prize for finding it? No. But if you find it, go put it at forum.macrevab.com?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Go post about it. Now, I'll click click the little heart icon if when you post about it.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. We'll we'll give you a digital pat on the back. No. By the way, this this glossary is like 100 of terms that all apply to manufacturing and electrical engineering and PCAs and PCBs. And I was telling Parker when I was reviewing this earlier, I was like, this this this is something that they should do in college.

Stephen Kraig:They should just give you this and be like, these are the things that are worth knowing.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. This is

Stephen Kraig:I had to give this to to interns at work and be like, if you have a question about something, go to this first and then come back.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I'm hoping it helps out some people. So

Stephen Kraig:It's at at a minimum, it is a really good resource in one place. It's also probably SEO for you guys. Right?

Parker Dillmann:I think that's why they originally wrote it.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. What?

Parker Dillmann:So because I didn't I actually didn't have anything to deal with this too much. I'm just promoting it.

Stephen Kraig:This is a lot of work whoever put this together. Oh, yeah. Hats off to them, and thank you because this is actually some really good stuff.

Parker Dillmann:I I think it was, Mireille. I I think Pamela worked on it too. I have to check. I know Mireille was working on it a lot though.

Stephen Kraig:Because this this is not like AI just crapping stuff out. This is somebody, like, putting effort into

Parker Dillmann:Oh, I bet your AI has already gobbled this thing up though.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, yeah. 100%. You guys are feeding the monster.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Some monster.

Stephen Kraig:But at least you're feeding the monster with, like, human created, like, accurate stuff.

Parker Dillmann:Accurate stuff. Yeah. So go check that out. It's maccred.com/glossary. Alright.

Parker Dillmann:On a personal project updates, this is a rare double back to back Steven Parker only episode.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:So you actually get, like, what I've been working on for the past week.

Stephen Kraig:Wow. So it's car related.

Parker Dillmann:It is car related. It is the PWM fan controller. I actually now have a thread on our forum, form.macro.com, for the PWM fan controller. The schematic is for all intents of persons, all intents and purposes. I gotta slow down sometimes.

Parker Dillmann:The schematic is complete. And so I don't know if you want to do a schematic review right now, or do you wanna do that at a different time?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, like we were talking about, like, many many episodes ago?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Well, I haven't picked the components yet, but this is more of a schematic review to see if there's anything I need to change before I start picking parts and putting the board together.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, live schematic review. I'm down for whatever. Yeah. Let's do that.

Parker Dillmann:Because there's 4 sections on the schematic review I want to do, and I actually outlined these in our form. So if you go to our form, form.macro.comform.macro.comform.macro.comform.macro.com. If you go there, you'll find the thread. It's gonna be at the very top. I should just pin it so people can find it since we're gonna be talking about a lot.

Parker Dillmann:I actually took excerpts of the schematic and posted it in there, so we're gonna be talking about these four sections. It's gonna be the PWM outputs, the digital inputs, the thermistor inputs, and the push pull current drivers. Because the rest of the circuit is all just normal digital logic non interesting stuff. I mean it might be interesting to some people, but to me I'm like yeah, I'm using a microcontroller I've used before. I'm using a USB interface I've used before.

Parker Dillmann:Nothing too super exciting there. So the the PWM output which is the main reason to build this is to send a PWM signal a 12 volt PWM signal to an electric fan. And this is not even high current, this is just a PWM low, low current signal. And so, what I have is a n channel MOSFET that is the gate of it is pulled down with a 10 k resistor to ground and then the IO the 3.3 volt IO from the microcontroller goes through a 100 ohm resistor. It's kind of like a gate snubber because we're only driving this with an IO pin, so you can't you can't just unleash all the currents.

Parker Dillmann:To get your your your IO drivers on your mic controller will not be happy if you do that for very long. So put a little snubber there and then the drain side of the FET is pulled up with a 100 ohms, which doesn't sound like a lot, but I wanted to make sure that this thing can switch quickly if needed. It's actually only gonna be like a 100 hertz. It's the fans I've been testing is a 100 hertz PWM signal which is really slow, but I put a 100 there so you can actually switch it fast enough or quickly. Actually I don't know how fast this thing could switch until you start getting too much slew.

Parker Dillmann:I guess we can simulate it but then yeah and then that drain that pulled up drain is what gets sent out into the world. There is some ESD Protection on the actual IO pin that goes back to the microcontroller that goes through a it was the chip I said last week which was the sp 721. It's like a, it's a silicon controlled rectifier diode chip thing that, prevents over over voltage and, transient voltages and stuff like that. Pretty cool little chip. I don't think there's much.

Parker Dillmann:I I mean, this is a pretty simple circuit. I don't know there's anything else I can really do here, that it could make this better.

Stephen Kraig:I I have one suggestion that I think it's minor and I doubt in this circuit it would even apply, but in general with, you got your gate snubber on the other side of your pull down resistor. I think it's better to put the gate snubber on the front end of the, the pull your pull down resistor. So in other words, the gate snubber should be right at the gate. And right now, you have it on the other side of the resistor. I would I would just change that one thing because the whole purpose of a gate snubber is to swamp or reduce the parasitics right around the gate.

Stephen Kraig:And, and so putting it as close as possible to that, to the, to the gate as you can makes the most sense. Now, this is just a low side switch. It's not gonna oscillate, like, it's just not gonna be a problem. I'm just saying like in general that's good design practice.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. What's interesting because that's a that's a different end goal with than what I was designing it for. Because I'm more worried about the the driver in the microcontroller basically because it's in theory basically when you turn 3.3 volts on and you don't you basically have a capacitor on that gate and it's gonna wanna gobble up as much current as it can as fast as it can and which can like instantaneous current is really high and so you want to slow that down. So putting that 100 ohms snubber on the other side of that pull down is fine.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. The only thing is, I guess, on the only thing is it might slow down you closing the FETs. That's about it, and that's not a lot.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah, and I just given the purpose of what you're doing here and the voltages that are happening, that's not gonna be an issue.

Parker Dillmann:Alright. Let us know in the comments on form.myfhead.com, which one you would prefer. But you you are right is flipping that around.

Stephen Kraig:You also have a very slight voltage divider here.

Parker Dillmann:Very slight.

Stephen Kraig:So it's you're losing 1%

Parker Dillmann:of your voltage with this. Flip, I'm writing this down. Flip gate snubber.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Put basically the the gate snubber touches the gate of the device.

Parker Dillmann:Alright. So next circuit we're gonna look at is the digital inputs. So the digital inputs, are gonna be active low.

Stephen Kraig:Okay.

Parker Dillmann:Active low, so this is like switch inputs. This is looking at stuff like your, AC high pressure switch to see if, like, you need to turn your fan on to, because your AC is on your air conditioner. And so this is a, so yeah, active low and so the, actual signal is gonna be basically that comes in can be floating, and so we have to pull that up to 12 volts. So we have a 10 k resistor pulled up, and I do have, like, a point 1 microfarad part, capacitor there just to kinda help smooth stuff out because that that could be a wire that goes into the engine bay and out into infinity. So it can pick up noise, so we're gonna go, hey, let's just put a little just a little capacitor there just to help smooth some stuff out.

Parker Dillmann:Now but this has to get into our 3.3 microcontroller so we we basically next thing is we go through a voltage divider but we are not only at 12 volts it's a automotive system so it can be technically max is like 30 volts like peak transients, but you don't have to worry about that because it's very short time period. 14.7 volts is about max. So basically my resistive divider here is for the max voltage of the system, which gives us like 3.25 volts coming out on the on the IO side. Okay. To that voltage divider.

Stephen Kraig:I guess I wait. I I guess I'm reading this incorrectly. Am I is it right to left or left to right? Your your AC override in pin

Parker Dillmann:Is coming from the world.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, okay. So so I I was reading this left to right. Yeah. So that so right is is your input and left is your output.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Left is the microcontroller.

Stephen Kraig:Got it. Got it. Got it. Okay. That this circuit makes a lot more sense now.

Parker Dillmann:I can imagine so. Yeah. Yeah. And so, yes. So our AC override in, which is from the outside world, goes through that voltage divider.

Parker Dillmann:And then halfway through it you know on the voltage divider part we go through a snubber and then into the IO pin and then in the middle of that voltage rail or voltage divider, I do have a a, a zener diode at 3.6 volts just to clamp anything that might go over

Stephen Kraig:Mhmm.

Parker Dillmann:Just in case. And then there's also another point 1 microfarad just sitting on the output, to help stabilize the output of this circuit. Because again this circuit is not gonna be switching really fast. This is going to be like a 0.1 Hertz max. Like, okay.

Parker Dillmann:1st. I was about

Stephen Kraig:to ask because you you are you are making a little bit of a filter here.

Parker Dillmann:It's a little bit of a it's a little bit of a low pass filter here, because you gotta think that the inputs are actual switches. Like, it's coming it's like a switch on a pressure line or a switch on your dash. That's that's what these are for. So these are on, like, the fastest things gonna switch is someone trying to hit a toggle switch as fast as possible for some reason.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. So This is also not really because you're you you have a capacitor inside of this divider. It's not really a true low pass filter. It's like a low shelf kind of thing.

Stephen Kraig:Yes. Yeah. But but in terms of what that in terms of the impact of that on speed, this is pretty minimal.

Parker Dillmann:Mhmm.

Stephen Kraig:And and like you said, it you you don't care. You you're not putting a PWM back into this. No.

Parker Dillmann:No. That's not what this is for. I say digital input. It's a switch input. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Okay. Physical switch. The fact

Stephen Kraig:that you're pulling this up to 12 volts, but your output can be plenty above 12 volts.

Parker Dillmann:It it Well, so that 12 volts that 12 volt rail Yeah. Is connected to the system 12 volts. So that 12 volt will be like that 14.7 volts.

Stephen Kraig:Sure. But you you said your output could spike up to, like, 30 or something like that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So the input of this whole system is is snug too. Like, if you go actually go into the power input, there's, like, a snubber to help prevent that 30 volt from propagating anywhere else to system. Okay.

Stephen Kraig:Because, yeah, that was my next question is why not just put a diode in series just in case it back feeds?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. That's that's already taken care of That's

Stephen Kraig:taken care

Parker Dillmann:of somewhere else. Stream. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Got it. Okay.

Parker Dillmann:Yep. Yeah. So this is this is literally basically so you can hook up a switch and then the other side of the switch is to ground. And so when you switch the switch it, you know, pulls the ground and activates the circuit

Stephen Kraig:or Is there any concerns with pulling, this input up to 12? Any concerns for the outside world?

Parker Dillmann:If if you if you pulled it up to 12, it would still be connected to this circuit except there'll be on the other side of the fuse.

Stephen Kraig:No. What I mean, you, the you are pulling it up to 12 here. Does that affect anything on the input? Like anything that's connected out there. Everything's fine with being pulled up to 12 is what I'm getting at.

Parker Dillmann:Right? You mean this AC override in?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And you connect that That's what's okay with being 12.

Parker Dillmann:Yes. That's okay with being 12. And it's also through that 10 k resistor. So, like It it yeah. It would limit

Stephen Kraig:the current.

Parker Dillmann:It would limit the current. So if that wire actually hit ground, it nothing bad is gonna happen. Right.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Right.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Okay. I I was playing around with, like, optocouplers and stuff to make this work, and I'm like, that sounds like a lot of work that a couple resistors and a diode can do.

Stephen Kraig:It depends on if you need isolation or not, which doesn't sound like you do because the car is one system

Parker Dillmann:and It's one system. Yep.

Stephen Kraig:And and, you know, if you if you were really really worried about, like, a really noisy environment, then sure. But it doesn't sound like this matters.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. The original prop fan had optocouplers for that, and they have not really needed them. It didn't matter because I that's what I thought is I thought like isolation would be important. It doesn't matter because like you your entire chassis ground most automotive stuff is not isolated. Everything just shares the ground.

Parker Dillmann:Everything's fine. All you really have to worry about is crazy voltage spikes because something bad happened. Sure. Like a battery got disconnected or you got in a wreck or something like that. Because you gotta remember you got 12 volt lines on a battery that's huge.

Parker Dillmann:So it it does like to smooth stuff out really well.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah, it doesn't like change, right?

Parker Dillmann:It doesn't like to change really fast because they can it can just keep gobbling up that change. Yeah. A lot. Oh, what's interesting about that? Slight tangent.

Parker Dillmann:So more modern so like old school alternators, I guess it's probably up till the mid aughts they were this way. Like there was an internal regulator on your alternate, and then before then 7. It's different like, you know, back in the sixties. We had generators, but anyways alternators. You have a internal regulator that has a sense wire so like sense wires on your battery so it takes care of like voltage drop and that kind of stuff, but it's kind of like an all self contained system to improve efficiency fuel efficiency because active you know, your alternators pulling 4 or 5 horsepower off your belt to charge batteries and that kind of and run everything in your car.

Stephen Kraig:Right.

Parker Dillmann:So to improve efficiencies, what I know this is what GM does. I know a lot of other manufacturers are doing this is they they start doing, like, smart alternator control, and so on, most of the time it only charges your battery up to 80%, and then it just like free wheels the alternator and like it basically lessens the field windings, so it doesn't take as much resistance. But they basically found is like to charge it up even more what it does is when you start braking that regen breaks with the alternator too and helps slow the engine down through that. So it will increase the field windings and charge your battery up more. Wow.

Parker Dillmann:So they got some fuel efficiency gains by basically when you're cruising and you're over 80% state of charge they go well, that's good enough to where you're gonna be able to start the car several times with what's in that battery already. We don't need to get up to a 100%, and we can just charge up higher when you're braking and not actively using the engine. So cool stuff. This is not doing that, but I just thought it was cool tangent because we're talking about alternators and charging and voltages.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Cool cool stuff. Yeah. Yeah, that's that's the digital input, if someone can make a convincing case that this circuit is bad, I'd love to hear because I actually came up I bet you there's circuits like this that exist, but I kind of made this myself. So it's Sure. Probably got some weird edge case that I'm not thinking about that can go bad.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, it's a it's a it's a voltage divider with some voltage clamping and some filtering. Yep. And

Parker Dillmann:and a pull up. And a pull up. But, give it a look. Let me know what I can prove. Don't say just put an optocoupler because I'm not gonna put an optocoupler.

Parker Dillmann:An optocoupler costs like 10x the price, actually probably more than that. It's probably a 100x the price of these parts, so.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. If you're trying to get this done as cheaply as possible, you you probably even have more components than you need.

Parker Dillmann:I probably have more components than I need. Yeah. Make that work.

Stephen Kraig:So Alright. Have you considered gosh. Let me think about this. The low voltage condition. Because you consider the high voltage condition, but what happens if your input is on the low end?

Stephen Kraig:I guess, the the pull up corrects that. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it's like floating. I mean, if you pull the switch down, that's the that's the application for that.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Okay. Never mind. You you you're right.

Stephen Kraig:You're right. Yeah. I'm so used to at work. We we always have to look at all edge cases, both top and bottom. And so that my mind immediately went there I was like wait, never

Parker Dillmann:mind. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:The purpose is for this to go low.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Purpose is to go low. Yeah. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Well, I guess I guess the other the in this situation the the potentially the low situation would be if your 12 volt rail was on its low side. So Yeah. Let's say the the tolerance of the 12 volt rail was 11 volts, not 12. Will this still function?

Parker Dillmann:You you know, actually, that's an interesting case is to do the math. I'm gonna write this down. Is do the math for, like, 10 volts. So, like, if your battery is low, you don't want it to turn on your fan because that's gonna drain your battery even more.

Stephen Kraig:Correct.

Parker Dillmann:So is is on the digital input is do do the maths on low battery. Well, okay.

Stephen Kraig:But but, actually, I I I think I would make an argument that even if your battery was at 10 volts, you would still want this circuit to function. You just want to be able to read your battery voltage and your your brain box says don't function or don't turn on fan.

Parker Dillmann:Exactly. What's, you know, what's interesting is the I I don't have it broken out because it's just a voltage divider on the 12 volt rail, but I do have where it's reading the rail to see what the battery voltage is. So you could be like, hey, if I'm reading a low battery and my digital input is always low. I I I need to do the math and basically look at the what the trigger point of the sandy 21 g is Right. The microphone I'm using.

Parker Dillmann:If you're like, if I'm at 10 volts on this IO is that gonna trigger as a higher low on my input?

Stephen Kraig:Are you in that gray zone where you don't know?

Parker Dillmann:Oh, don't know. That's even worse.

Stephen Kraig:It's way worse.

Parker Dillmann:Because if it's way worse then I go, well, I'm just gonna connect this to an analog input now.

Stephen Kraig:You you know, honestly, one thing that I think would be fun with this is to throw this circuit even though it's just a simple voltage divider, throw it into LT Spice, put your tolerance of all your components in it and run a Monte Carlo simulation. Do a 1,000 simulations and see with all just random tolerance on all your components, what is your range. Yeah. That would that would be fun as well.

Parker Dillmann:Because I am going I'm using 1%, automotive grade resistance.

Stephen Kraig:I'm sure you're fine. No.

Parker Dillmann:No. That's great because I actually wanna know, like, if it's on if it's got a low battery and the tolerances stack up is just the right way, am I not gonna be able to trigger a high on that input pin? And so it's gonna think that the AC needs to be cooled down. The the AC, condenser needs to be cooled down, and goes, well, I need to turn the fan on and pull 80 amps now. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Right. I'm gonna throw I'm gonna throw one more thing at you on that. Vary this across temperature as well. In fact, just do the Monte Carlo at what's what's what's car temperature, typical ranges?

Parker Dillmann:Freezing to 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

Stephen Kraig:I would actually say less than freezing. Cars regularly driving lower than freezing.

Parker Dillmann:Negative 40 Fahrenheit is the low end of the parts for automotive grade.

Stephen Kraig:So say negative 40 negative 40 c to 85 c, something like that. See, will it work across that entire range with varying tolerance as well. In in other words, you I think you could you could run 2 Monte Carlos, one at negative 40, one at 85 with your dollar shift.

Parker Dillmann:Hey, you make me do a lot of work.

Stephen Kraig:I know. I know. Make me do engineering work. This is real engineering. That's real engineering.

Parker Dillmann:You are right. That is that is

Stephen Kraig:what it is. It's boring. I like this. Yeah. Now, okay.

Parker Dillmann:Go ahead. No. No. No.

Stephen Kraig:You you get you have 1 or 2 more circuits to go?

Parker Dillmann:I have 2 more circuits. Cool. Alright. Because I know we're at time, but

Stephen Kraig:No. No. No. This is great. Keep going.

Stephen Kraig:Analog inputs. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:And so these are designed to read thermistors. These are not like current, driver like you know 4 to 20 milliamp or anything like that or voltage output drivers from sensors. These are thermistors so they are ntd, you know, negative temperature coefficients temperature sensors. It's a resistor that just changes under temperature. And so these circuits I literally lifted these from other engine control systems.

Parker Dillmann:So these these this is what the big players do too. And the values are weird. I don't know what the historical numb reasoning for some of these values are, especially the 2.49 k pull up, but everyone uses those. Mhmm. Like you can go to like automotive sensors like the OEM for the sensor, and they'll give you a chart based off a 5 volt pull up for 2.94 k.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. Kind of weird. Just a classic value?

Parker Dillmann:Classic value in automotive. Now I don't have a 5 volt rail so I can't use those charts. Actually, technically, yes, I can. I can just I what I did is I made a spreadsheet to convert the 5 volt pull up to 3.3 volt pull up. Just to rerun the math for what the

Stephen Kraig:voltage whatever the whatever the base baseline current is yeah what

Parker Dillmann:the baseline current will be because I'm still doing a 2.49 k pull up, but I'm only pulling up to 3.3 volts because that's my rail And then there's basically a low it's actually a low pass like pie filter where you have 2 capacitors and a and a I think it's a 2 point 2 k resistor in there as like a as a filtering. That's all it is. And you got thing is on the on the out on the input of this is a, thermistor to ground. So basically, it's a it creates a the thermistor creates a low leg of a voltage divider there. And now of course on the IO side there's also that SRC protection IC is is there too, so it's preventing transients and overcurrent situations on the out I don't think there's much to talk about there unless someone is like, that's bad idea and his way to improve it.

Parker Dillmann:That's because what this is what everyone else uses. That's why I went with this.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I I guess just the the series 2.2 k resistor that goes into the analog pin. I get is that just for filtering? It has a a 1 microfarad cap. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:The ground

Parker Dillmann:cap rate. Filtering. Yep. Okay. I think that's what that's for.

Parker Dillmann:It's just to help smooth out whatever signal you're getting off that that thermistor.

Stephen Kraig:Do you know what the input impedance is of your analog reading? Because just because you have 2.2 k is high enough that if your input impedance on on your analog inputs is low, that can affect your readings.

Parker Dillmann:I don't know what it is on the Sam d. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I would say that's worth just checking because that would just effectively appear as an offset. Right? For for readings or or if there's any leakage which there should be very little. So I don't think it's a huge ordeal. It's just something to consider.

Parker Dillmann:Let's see. I'm looking at samd21adcinput impedance.

Stephen Kraig:Like, I'm just throwing a number out there. This is probably ridiculous, but if they had like a 10 k input impedance and they needed to be buffered, this this, 2.2 k in series would would cause some issues. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:I don't know what the n p n pence is.

Stephen Kraig:I think it's worth it's worth looking that up just so that you have you're not just cooking in inaccuracy.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. I'm trying to see if there is a impedance on the datasheet that I can quickly find. I can't find anything really quickly.

Stephen Kraig:Let's see here. I'm just on a random website. Input impedance appears to be somewhere in the

Parker Dillmann:40 kilo ohms. Really? Yeah. According to Sam d 21 datasheet page 991. I didn't know that.

Parker Dillmann:40 k.

Stephen Kraig:40 k all the way down to DC. That a Okay. So, you might you might start running into a little bit of inaccuracy with that.

Parker Dillmann:Right? Then literally, the next post is 3.5 k.

Stephen Kraig:What? Okay. It sounds like there's some more research that needs to be done here, but regardless if it is pretty low, yeah, then you need to either buffer it or consider Mhmm. Some other kind of situation or circuit.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I have to

Stephen Kraig:see what the actual input opinions is on it. So it might be worth putting like a voltage follower there. Because because if it is just acting as a 40 k input impedance, you have a 5% error just from having it that series resistor.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, that's about the error of the sensor though.

Stephen Kraig:Well, okay. But you're you're stacking that on top of it.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That's true. But it could it could stack it in the opposite direction.

Stephen Kraig:Sure. Yeah. It's you're okay. So you you've tuned your error.

Parker Dillmann:Possibly. Who knows?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. So that sure. May maybe a little op amp buffer would be helpful there.

Parker Dillmann:That might be the right place. Put a, like a dual pack because I have 2 of these inputs is put a dual package op amp.

Stephen Kraig:And just do a just do a a unity buffer and you're getting.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Just like I think I actually have designed, like, a, what's what's it called? A, instrumentational instrumentational, amplifier.

Stephen Kraig:Sure. That that's probably way more overkill than you need. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:But it's already designed, so I can just put on the board.

Stephen Kraig:That's how Parker designs. But I already have it.

Parker Dillmann:Already have actually, I think I have another one that's just a generic op amp that I can plop down down to. That's like an issue.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And I mean, the voltage range on this is nothing.

Parker Dillmann:So Yeah. 3.3 volt. Right. But,

Stephen Kraig:it depends on how low you needed to go. Because if you're trying to single supply this and get it to go down to ground.

Parker Dillmann:No. There's a baseline.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. So it's always above ground?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's always above ground. Cool. Yeah. The the, resist the resistance of the thermistor won't hit 0.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. The resistance will never hit 0. Do you ever need it to go all the way up to 3.3 volts? That would be the situation where you have a sensor unplugged, basically.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. If your sensor's unplugged you actually should be able to detect if it's unplugged or not as well. Because then you can throw an error. It's like, hey, my sensors unplugged. I'm gonna run at it like a baseline speed because I have no idea what the temperature can be.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right.

Parker Dillmann:Yep.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I guess you could just have the the brain box know if it's this value. If it's above this value then consider that an open probe. Yep. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. Yeah. I think I think that's your best bet is just throw in a little buffer.

Parker Dillmann:I'm making a note. I put op amp bugger instead of buffer. Okay. So in the last circuit that we're gonna talk about is I don't know what the best way to call these. It's a but it's a it's a push pull current driver is what I'm calling it.

Parker Dillmann:It's an h bridge.

Stephen Kraig:Well, half h bridge. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Half h bridge. Yeah. And there's 2 of them, though, but they're for 2 different outputs. Right. Technically, I guess you can control a motor with it, but that's not what it's for.

Parker Dillmann:It's the control. It's the control relays. It's the control indicator lights anything like that that's what's for and also this is it's

Stephen Kraig:just a circuit that can sync or source

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's a circuit that can sync or source so it can it can output 12 volts or it can sync current from something else. So you can put a motor on it. It's actually designed to be like I think it's like 4 amps at 12 volts. Mhmm.

Parker Dillmann:And so I have a fuse on the output and, so that that way you if it's sinking or sourcing it doesn't overcurrent anything It's using a p channel and an n channel and then the p channel is switched with an n channel FET. So the older logic is the same. I think the only big thing with this circuit that could be improved is maybe like a logic gates on the IO pins that prevent both from being active at the same time.

Stephen Kraig:Just being a dead short.

Parker Dillmann:So you don't have a run through situation.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:I on the software side, I'm going to put in a check. So, like, I'm gonna, like, when I do the software, I'm gonna, like, this part of the code will be its own like, you will call a function that will set the PIN. Right? But there'll be an actual, you know, function that will actually set the registers, and that function will check to make sure that these are not set the same.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right.

Parker Dillmann:And if it is, then throw an error, and don't do it. But we should probably put just put some software lodge or firmware. We should put some hardware logic right here just to Double make sure and also like what if you have a failure of a IO driver off your microcontroller? So like a like an I input a, a pin gets stuck high or something like that. Mhmm.

Parker Dillmann:So

Stephen Kraig:I do see one thing that that that needs to be swapped on this. So u twelve, your pFET.

Parker Dillmann:It doesn't

Stephen Kraig:need to be swapped, but it needs to be flipped vertically because as of right now, the the source and drain are in the wrong positions and the body diode will just conduct straight through.

Parker Dillmann:You are right. Yeah. Oh, I fucked that up bad, didn't I?

Stephen Kraig:Right now, it would just straight up turn on.

Parker Dillmann:Yep. Flip the p channel. This is why we're doing a review.

Stephen Kraig:This is why we do it. Yeah. The other thing is the similar to your first circuit, the gate stoppers, just move them right to the gate. Yep. Technically, r 43, which is your, like, your high leg pull up, that could constitute your gate stopper for u twelve.

Stephen Kraig:Just depends on how you lay it out.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, yeah. Yeah. That was the plan.

Stephen Kraig:Yep.

Parker Dillmann:Because I'm I'm not worried about like so that gate on u 12 is connected through the drain on u 13, which is the end channel that opens it up. Like, I want that to flow as much current out as it can, so I'm like, I don't want any I don't want a snubber between that gate and the drain of u 13. I want that to flow turn on as fast as you can. And those, like, this is not designed a PWM or anything is literally like the driver relay or something like that, which you also don't want to pulse. So You're actually probably putting some small capacitors on those gates as well to kind of keep them more stable might be worth it too.

Stephen Kraig:You can always, just non pop just put a put a

Parker Dillmann:pop up

Stephen Kraig:down and not pop it.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Just see if that is becomes like an EMC issue. Sure. And be like, oh, I'm just gonna you know what, actually, on that output, I should put clamping diodes on that output. Unlike the, actually, I wonder should I do it on the out of the fuse side or actually, yeah, it should be.

Parker Dillmann:On past the fuse before it leaves is where I should put some clamping diodes. And what I'm thinking there because this what I'm using these for is to drive relays. Big relays too and so if that if one that the relay doesn't have its own snubbing diode. Now I have them built into my circuit. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:On your flyback diodes. But also, if that fuse pops, that relay is gonna wash it off. Right? And putting those putting those diodes, let's say, closer to the FETs and on the other side of the fuse doesn't help that relay at all. So putting those diodes closer to the output might be the way to go.

Parker Dillmann:I'll write that down as I need to put

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. No. I like that.

Parker Dillmann:I need to put an output, flyback diodes. I mean, technically the the body diodes of the of the FETs do that too, but that doesn't help with that fuse pops. I got some stuff to change.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I like your idea of putting, some hardware logic in to prevent the situation that they can ever both be on. Even though there's not a software condition that should allow for that. I

Parker Dillmann:I think

Stephen Kraig:I think a a an honest to God, just some logic gates in front of these things

Parker Dillmann:Yep. To just force that. Yeah. Just to force it. The part b a and gate.

Parker Dillmann:Well, 2 and gates probably.

Stephen Kraig:I think you can do it with an XOR and another An XOR. Yeah. Yeah. Because an XOR is gonna give you a 0 when they're both high.

Parker Dillmann:Yep.

Stephen Kraig:And then, I don't know. There's a handful of ways you could pull it off. But I I think I don't think there's gonna you can't do it with 1 logic, Kate. I think you need a Correct.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. You need 2 XORs will work. Yeah. I think that's right. Yep.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That'll work. Well, a quad XOR package is what I need because I have 2 of these.

Stephen Kraig:Because you have 2 of these circuits.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So I have 4 IO pins.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Cool. I I I guess I'm a little bit curious. So is this output supposed to just be a general purpose output?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So because the design's open source, so you can technically write whatever software you want on it. So, yeah, you can you can make this drive whatever you want. I'm gonna use it to turn our big chunky relay on, but you can do whatever you want with it.

Stephen Kraig:The the the only thing I'm I'm thinking, you do have it fused, which is good, but right now there's nothing like if you just took this output and connected it to ground and said go, this thing would give you everything it can. It would just puke its guts until the fuse pops. Yeah. So

Parker Dillmann:So the 12 volts that it's getting is Yeah. Fused on the input Yeah. To the device and, there's that fuse there. Right. And so that fuse is gonna be a actual it's well, it's gonna be a PTC fuse, but it's gonna be lower than what the FETs are rated for too.

Parker Dillmann:So all the traces and everything we overspent.

Stephen Kraig:Sure. Sure. Is that PTC faster? Will that work faster than the the

Parker Dillmann:FETs deciding to

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. The source itself. Yep. Right. Right.

Stephen Kraig:Exactly.

Parker Dillmann:The GRU eating the FET?

Stephen Kraig:I'm just wondering if it makes sense to put a small amount of resistance in line just to act as a a a really cheapo current limiter. I mean,

Parker Dillmann:that's what a PTC, it already kinda is.

Stephen Kraig:I I guess. Yeah. Yeah. I guess you're right.

Parker Dillmann:Because I could put, like, an actual automotive fuse there, but I don't really want to keep opening this thing up if when, you know, if if the fuse was external, it'd be totally fine, but the fact that it's gonna be internal inside this, like, box that's watertight. Having to open it up to replace the fuse is gonna be a pain

Stephen Kraig:in the butt. Does it, I don't does it make sense to have any kind of Here's some fun word for you, telemetry read back. In other words, on the output, does it make sense to read the output with the microcontroller just to confirm that it's doing what it needs to do. Like, yes, I'm outputting 12 volts. So, yes, this is 0 volts or whatever.

Stephen Kraig:Oh.

Parker Dillmann:Just so that

Stephen Kraig:you, like, you could read it back and know that, like, you could you could sense an open or a short.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Like, on the other side of the fuse.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And then it could tell you, hey, this is messed up

Parker Dillmann:or not. Yeah. Just run that side of the fuse through a voltage divider and then put a TVS clamp on that input. Yeah. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:I have plenty of of unused IO pins on the microcontroller to do that.

Stephen Kraig:Do that then and so you can you can you can you know the help, like, you whenever you turn this on, you can confirm that it's on and that there's not an error or an issue.

Parker Dillmann:Feedback on