Purchase The Sleep Watcher

(0:27) Introduction

(3:37) Roman's childhood reads

(17:30) Ghosts and breaking boundaries

(20:39) Where to start writing

(35:11) Rowan's favourite book

(43:43) The Sleep Watcher

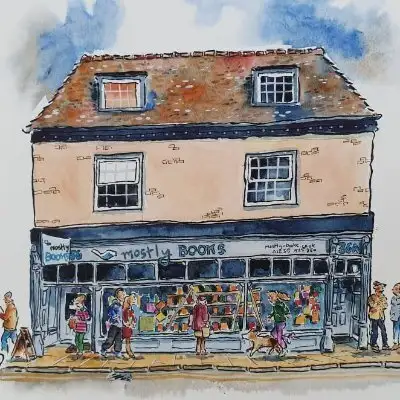

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a weekly podcast by the independent award-winning bookshop, Mostly Books. Nestled in the Oxfordshire town of Abingdon-on-Thames, Mostly Books has been spreading the joy of reading for fifteen years. Whether it’s a book, gift, or card you need the Mostly Books team is always on hand to help. Visit our website.

Meet the host:

Jack Wrighton is a bookseller and social media manager at Mostly Books. His hobbies include photography and buying books at a quicker rate than he can read them.

Connect with Jack on Instagram

The Sleep Watcher is published in the UK by Sceptre

Books mentioned in this episode include:

Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson - ISBN: 9780141191447

Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window by Tetsuko Kuroyanagi - ISBN: 9781568363912

Reverse Engineering by Scratch Books - ISBN: 9781739830106

Creators and Guests

What is Mostly Books Meets...?

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a podcast by the independent bookshop, Mostly Books. Booksellers from an award-winning indie bookshop chatting books and how they have shaped people's lives, with a whole bunch of people from the world of publishing - authors, poets, journalists and many more. Join us for the journey.

[00:00:00] Jack Wrighton: Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, the weekly incurably bookish. We will be talking to authors and creatives from across the world of publishing and discussing the books they have loved. Looking for a recommendation? Then look no further. Head to your favorite cozy spot and let us pick out your next favorite book.

It is my great pleasure to welcome onto the podcast this week, novelist Rowan Hisayo Buchanan. Rowan's first novel was 2017's Harmless Like You, which won a Betty Trask and Authors Club First Novel Award. Since then, she has penned Starling Days, and now this year she has released her third novel, The Sleep Watcher, an exquisite exploration of adolescence, family, and the complexity of love. Rowan, welcome to Mostly Books Meets,

[00:00:52] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Thank you so much for having me.

[00:00:53] Jack Wrighton: Our absolute pleasure. So on this podcast, we like talking to authors about their work, about the books that have influenced them, the books that they enjoyed, and also a bit about their life. So if we start by sort of going back to your early years, where did you grow up and were you always sort of interested in books and the written word?

[00:01:12] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: So despite my accent, which does confuse some people, I grew up in London, but my mother is Asian American and I lived there for a long time, so my voice is a bit puzzling, but I grew up in London and I didn't know that I wanted to be a writer, but I did always love books and reading and making up stories. But I think like a lot of people, I didn't really consider it to be a job that you could actually go out and do any more than it felt possible to be an astronaut or a movie star and I feel very lucky that I got to do one of those things.

[00:01:46] Jack Wrighton: It's a common theme speaking to authors is that early period where they're aware of something that they really enjoy and they may be reading books and they're aware that people have written them, but it seems almost impossible for that to be someone's vocation, which I don't know, maybe suggests a kind of, you know, something that needs to be addressed in what is made, you know, to feel possible, and in terms of the books you were reading, what, what type of books were you sort of reaching for at a young age? Were you in a house full of books? Or was it in a sort of local library that you were coming into contact with these?

[00:02:19] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: So I was very lucky, because it's London, obviously there were excellent local libraries. Please support your libraries, dear listeners. But I was also very lucky in that my, both of my parents have books, but especially my mother, and so she very much encouraged that love from an early age and I did have my own books as well.

[00:02:44] Jack Wrighton: It's very interesting, you know, always learning about where people sort of came across books, because some people, yeah, they grew up in houses of books, and some people, as you say, come across them in a local library, which is why it's so important, even though we're coming here from a bookshop, people always feel that somehow bookshops would be sort of anti library, which we have to say no, not at all, you know, we work very closely with the local library and it's, it's all kind of part of a very important sort of ecosystem, and you know, talking to many authors, those kinds of local institutions have been so important to their kind of development.

[00:03:19] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I definitely have people who tell me they've taken a book of mine out of the library and they enjoyed it and then maybe they've gone and bought a different book that I wrote and, you know, they're very much, I'm always delighted if someone tells me they took my books out from a library. So yes, I absolutely see what you mean about it being an ecosystem.

[00:03:36] Jack Wrighton: And, in terms of sort of individual titles that you sort of remember from that time, are there any that stick out to you that you would sort of, you know, recommend to our readers to make you a sort of bookseller for the day?

[00:03:49] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: There was a book that I have been thinking a lot about lately called Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window, and it's by a writer named Tetsuko Kuroyanagi and it was sent to me, I think by my relatives, in translation, I read it in English. But it was a huge bestseller internationally and in Japan, and it's about this little girl who's growing up in Japan, pre World War II, and she's a little bit different. She's not good at sitting down at her desk at school. She gets in trouble for crawling under fences, for talking to birds outside the window and she gets expelled from her normal school and her mother doesn't tell her she's gotten expelled, she's like, oh, we're going to go to this new different school and she ends up going to a school that is Inside of train carriages. So it's a train that's now disused, that's been turned into classrooms and this is a memoir, by the way, it's real. So she goes to this school and all the children in this school are a little bit different.

So the writer doesn't say why she was different from the kids around her, other than, you know, the specific instances, but she doesn't have a diagnosis, but there are kids at that school who have polio, who have developmental disorders, but it's not a school where they tell them, oh, you're, there's something wrong with all of you. It's just a school where there's a quite progressive headmaster, and he tries to have a form of education that will suit them all and a lot of the anecdotes are just about like beautiful, joyful things for kids do like learning how to cook pork soup or their school sports day where all of the awards are vegetables and they can all take the vegetables home and cook them and then, you know, it's the first time they're providing food for their family and, you know, it's almost conflictless.

It's just like this lovely, lovely place, but it's taking place just before World War Two. And so you see some, very much from the perspective of this little girl, but hints of what's going on, wrong in the world. So there's a local Korean family who don't go to the school and she's walking past the little boy and he's very angry and he shouts at her, Korean! And she doesn't understand what's happened. She goes to her mother and says, you know, what's going on? She said, well, he's too little to understand that when people shout at him in a mean way, Korean, they're talking about his ethnicity. He just thinks it's an insult, like to say idiot. You know, and so there's this touch on this like, this discrimination that's happening, and then as the book continues, you start hearing about rationing, their soldiers going to the front, her father is a violinist and he refuses to play in the munitions factory, even though then they could have food in their family because he doesn't believe in the war and then, and this, this isn't, I don't think a spoiler, it's not the sort of book you can spoil, but something terrible happens to the school and I remember reading it as a child and being absolutely shocked, you know, this sweet school we've had all these fun and it could be affected by this huge thing and I was rereading it and as an adult, you can see it coming. You can see. the machinations of the world. But as a child, I was so caught up in imagining myself in that school and in the beauty of the idea that it absolutely broke my heart and I don't know if that's a good way to say this book will break your heart, but I think it felt like a really honest child's eye view of the way the world impinges, but also of hope and the ways we can treat each other better and I read that when I was about, you know, nine, ten. You know, it's written in very simple language.

[00:07:55] Jack Wrighton: Would you say it was written for children in mind, or was it a book that was just written that sort of was read by everyone in terms of the demographic?

[00:08:04] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: So I believe in Japan, it is studied in school classrooms, anyone could read it and I think, you know, as I said, rereading it, I got different things out of it. But because it feels very honestly written from that child's eye view, you feel, I think as a child, you can really understand and empathise with it. You know, I probably enjoyed the train classroom so much and all those stories because I am dyslexic and I'm dyspraxic and the idea, you know this, the little girl doesn't give herself a label like that. She doesn't say, Oh, I was ADHD or anything like that. But the idea that there was this magical classroom inside of a train, where you could learn in the order that you wanted to learn in and really meant something to me as a child and so I think there are... an adult will get different things out of it, but I think absolutely it could be read as a child.

[00:09:05] Jack Wrighton: That's amazing. I think it's a real testament to, well, firstly, I think what children can take in from a book. I think, you know, sometimes people feel that, you know, certain themes or things like that, you know, that children wouldn't necessarily get, but, you know, speaking to authors and coming across children's books in my, you know, line of work, you do realize actually that, you know, there's a great complexity there and that, you know, children are far more complex and able to understand things than they're given credit for, and yes this book sounds fascinating. You said, is it a good recommendation because you said it sort of broke my heart, but that is, people love that.

I always find it very strange. You'll sort of say to someone, Oh, this book, yes, it completely broke me and they'll go, Oh yes, I'll buy it and you think, yeah, we're such funny creatures that actually, you know, there's something sort of appealing to that and particularly, you know, it being a memoir that must, you know, to imagine this school, which sounds so amazing, I'm also dyslexic and dyspraxic. So I sort of understand that, that viewpoint and, you know, this school that sounds a sort of haven at a time where there, I imagine there wasn't much of a language for maybe some of the things that these children, you know, had now they would have a sort of, Oh, I am X, Y, Z, but then you would just sort of, you know, in some instances, just a kind of a problem child or someone who was a bit of trouble.

[00:10:28] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Yeah, no, exactly, exactly and I think, you know, the fact that this is a place where they aren't seen as problem children, you know, regardless of labeling, I think sometimes we use these labels now and they're really helpful, and they give us a way of saying, Okay, these are the accommodations I need. This is what would help me move more easily through the world and they're wonderful for that. But I think despite that, people can feel like, Oh, maybe this means I'm a problem and so I think, I don't know, I still want there to be magical schools on trains, where no one has to feel like a problem.

[00:11:06] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely. Particularly the train carriage, I think, just for a child, like, imagine the joy of turning up to your class in a train carriage. I do know of one school, which I've only seen on social media, that does have, and it's recently opened, its school library is in an old train carriage, which I think is just the most wonderful thing and I think it's maybe out in Wales, I'm not sure, I just imagine this sort of beautiful rolling hills with this train carriage. It feels, yeah, feels painfully idyllic almost. Like it's a bit too beautiful.

[00:11:40] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Yeah.

[00:11:42] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, very jealous. Yeah, very jealous of that school. My school library was definitely not in a train carriage and in terms of, so you're reading that at sort of nine and 10. How did you develop as a reader? We find some people we speak to, you know, they sort of dropped off in their teenage years, or they sort of remained a consistent reader throughout their lives. Which one would you say was true for you?

[00:12:05] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I think the key is that I was deeply uncool, so I stayed reading. When I was a teenager, I used to hide from sports by hiding in the school library, and I'm pretty short school librarian knew I was there, and the thing that makes me really laugh is we didn't get academic grades for sports, we got like an effort grade and my effort grade went up once I stopped going at all, because I think they didn't know who I was, and the sports teacher was just like, oh, this person, I don't know who I was showing up and being really bad at it, they were like, they remembered me, and they felt that was a try hard so...

[00:12:47] Jack Wrighton: Oh dear.

[00:12:48] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Yeah, books were always, always a haven. I think

[00:12:51] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, we're always, yeah, a place for you and of course, that's such a, you know, the teenage years are such a difficult and strange time, and of course, The Sleep Watcher very much, you know, focuses on that very sort of difficult time in your life where you're sort of, you know, not quite one thing, but neither another. You're in a sort of developmental stage. When you started writing it, was it, did you want to write about that particular sort of bracket in someone's life? Or was that not the kind of your first way into the story, did that come from elsewhere?

[00:13:25] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: it was definitely very much in the early conceptions of the book. So I think when I begin a novel, I usually have a problem or a question I'm turning over in my head and at the time I was thinking a lot about the fact that we have been through a period of exposing, especially male, but in general, violence and bad behavior generally, and saying we're not going to tolerate that anymore and I think that has been a really important correction, socially. But one of the things I was thinking about is, but what if you loved someone who'd done those things, who wasn't necessarily a straightforwardly good person and how would you handle that? Could you somehow erase, would it erase all of that love? And I think especially, this book is largely about a daughter's relationship with her father. That he has taken care of her and taught her how to sing and looked after her and that he is, he is her person and that's true, while everything else is true and I think I felt like if you were writing about an adult in those circumstances, they can leave, they can create space, they can say, my therapist says I need a healthy boundary. But there's a certain claustrophobia to being a child or to being a teenager where you can't do those things. You can't just create the healthy boundaries usually and it forces issues that otherwise could be ignored or swept under the carpet and so I think I always knew that the protagonist was going to have to be a teenager and sort of came later In the process realising that she was going to be telling it from the point of view of adulthood looking back and that emerged a little bit later.

[00:15:32] Jack Wrighton: So that almost came as a almost, if it's fair to say, a sort of structural decision. It gave you this kind of...

[00:15:39] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I think a structural decision, but I think also a character decision in that one of the sort of ideas or thoughts behind this book I suppose is that we all have stories that we tell about ourselves to ourselves and to the people close to us that say this is how I came to be who I am. This is me and I'm me because of this story and there are stories we tell, you know, people we've just met at a party and there are stories we tell our close friends and stories we maybe only tell our most loved ones and then maybe there are some stories we only tell ourselves and I always knew that this was going to be one of those stories and I felt like while we can have life changing moments as adults, there is something about those years when you are becoming who you're going to be that is particularly lends itself to those stories and those stories are also quite hard to escape once we've told them and it felt essential to her character to me, that this is something that happened to her growing up.

So it, I think, to say it was a structural decision, but that sounds very cold and like, I was organizing the chess pieces of these characters, and I think that is how some people write, and they write beautifully that way. But I think, for me, It feels more like a conversation I'm having with this character, so I'm trying to figure out what their story is, so it felt sort of essential to her, if that makes sense?

[00:17:11] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, absolutely, absolutely and obviously Kit in the book, you know, has these evenings where she sort of breaks the boundary of her body and sort of goes wandering and did that come out of being a constricted sort of teenager where you said, you know, you're trapped, you can't just leave? So did that then lead to this idea of suddenly being able to break through all boundaries, you know, of the body, of wars or did that come from a different direction? Because I think it's in the acknowledgements, you mentioned sort of talking about ghosts and getting to it that way. So where did that come from? I'm really, interested in that element of the novel.

[00:17:50] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I've always been really interested in the things that are on the edge of the true, and by that I mean, very few people have gone on a Lord of the Rings quest and believe that they have, I mean, probably someone's out there, and that doesn't make Lord of the Rings a wonderful book, it's, but it's doing something different.

Lots of people think they've seen a ghost, not everyone, not even the majority, but many people feel that they have sensed or believe that there's some other thing, some trace of humanness, and I think whether or not ghosts are real, unfinished business is real, revenge is real, the legacy of traumatic events is real and goes to maybe how we process it, or who knows, it might be real, and I think equally out of body experiences lives in that same place, where there are people who genuinely feel that they have out of body experiences, and there have been scientific tests about it, and one type of out of body experience, apparently, from what I've read, seems to be something you can replicate in a lab, which is if you, like, basically zap someone with the correct frequency of electricity, you can make them feel like they're observing themselves from another part of the room and that appears to be just a pretty straightforward neurological thing. But there are also people who feel they've traveled great distances, that they've seen things in a far away, that we have no evidence for, but people believe that they've been through it and so I think it's a really interesting concept.

But I remember myself being a teenager, and I should clarify this book is not autobiographical, but I remember being a teenager and not having any experiences, but absolutely longing to have them. That I could walk through walls, that I could get out of where I was, and sort of also being kind of intrigued by this, what would you see, what would you do? And so I gave this gift to Kit, the character in the novel, but I suppose a bit like a gift in a fairy tale, it's maybe not the gift it seems at first.

[00:19:50] Jack Wrighton: Yes, it definitely, it's fair to say it has, it has repercussions and of course, I think, you know, I think that's a, I think what's so interesting about books that explore, as you say, the things that are kind of on the fringes of the real is you can really explore, you know, what it would be lovely to sort of leave your body and to go wandering.

But I think for all of us, there would be temptations, there would be repercussions, and it, you know, exciting. I don't know if you agree with this, despite, you know, the sort of subject matter of the book, that that's just a really exciting thing as a creative to explore, you know, to look at that kind of darker stuff.

[00:20:29] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: It was fun. It was fun to imagine. I enjoyed writing those sections, definitely.

[00:20:34] Jack Wrighton: And did you, in terms of writing, did you sort of start with those segments when you're approaching a novel? Sort of, where do you start? That might seem like a silly question, but you know, I imagine maybe some start, you know, with the middle, with a particular scene, and kind of build out, or some start with the beginning. Where do you start from?

[00:20:50] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I think, so I often have ideas that's for a character and a mood, usually a place. It almost feels like a still image where I'm then trying to think, okay, who is this person? Why are they making that face? Where are they in this place? And a lot of those ideas come to nothing. But the ones which have become novels, I usually have very quickly an idea of what the ending is going to be, but I often have absolutely no idea of the middle, or how they're going to get there.

So, there's a scene very early on in the book where she's awake, like normally awake, she's not having a bad experience, and she is sitting on, it's night time, she can't sleep, and she's sitting on her father's lap and he's also sitting on his lap, even though she's a bit too old for it and it's like a loving moment, but also a slightly on edge moment and I sort of knew that I could sort of imagine this relationship, I could imagine this moment and then I knew that there was going to be a final confrontation, but I had no idea what exactly was, how we were going to get from one place to the other, and that was very much a process of writing my way in.

I know a novelist who put her entire novel into an excel spreadsheet where she had all the plot points. I think she even had like how many words roughly she wanted each section to be.

[00:22:19] Jack Wrighton: Wow.

[00:22:21] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: She successfully wrote a novel like and it really worked for her. I'm very pro anyone's process that works for them. That would not work for me personally though. I need to sort of find out who my characters are by writing I think.

[00:22:34] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, that makes sense. That, you know, it's sort of, well, you said earlier, you know, the, the decision of that sort of adolescence and things like that was a conversation, you know, with the character. So it's a kind of, you know, exploration and the book sort of emerges from that. I mean, I'm, you know, in awe and terrified of anyone who regularly uses an Excel spreadsheet because it's not how my brain works, but yeah, it's amazing and you know, I've spoken to authors on here that there is a almost like a mechanics to it. It's kind of like they lay out all the parts and then they go, right, I'll put it together and then, I've spoken to novelists such as yourself, which yeah, it's kind of more of a yeah an exploration that leads them there. And do you find obviously, you know, this is your third novel, I mean a question I always love is you know, do you feel like a more of a novelist after you've sort of done three? I'm always interested in the kind of the position of sort of being a writer, you know How it compares having your first book come out to how it compares sort of being three books in.

[00:23:40] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: That makes sense. I think Definitely the first book was probably the biggest change. I teach and I've had the students and they always, they say, can I call myself a writer? Can I call myself a novelist? And I think I always tell them they should claim any title they want. But I think for me personally, I find it very hard to call myself an author or a novelist.

But even a writer, before my first book came out, I had a lot of anxiety about it, perhaps. And so there was something absolutely magical about seeing my book on the shelf, and I am nothing against other formats, audiobooks, eBooks, but I think for me, my love is, it's the physical, it's the physical book. So that blew me away. It still does kind of, but I think, you know, if I go into a bookshop and I see it work. But I think the sort of change that happened since then has been a bit more gradual. I think, you know, there is some quote and I don't remember who to attribute it to, but basically it says, you know, we only, as writers we only have a sort of limited number of preoccupations and that's sort of terrifying and you think, oh, no, does that mean I'm just doomed to repeat myself again and again and again? And, you know, I'll leave that to my critics to see if I did it. But, from my point of view, you know, that is at first alarming, but then you actually go, no, okay, if something is large enough to obsess you, to make you want to write multiple books about it, that there are probably multiple angles on it, multiple ways of looking at a particular set of ideas or looking at the world and I think having written three books, I have more of a sense of the types of stories that I want to tell and the types of characters I want to talk about and I think that you sort of begin to know yourself a little bit and that's always a key thing. Oh, but maybe I will write my great space war novel and who knows I might but there'll probably be people who are quite flawed and who are trying to figure out a way to be human and to love each other during the great space war and then we'll be like, oh, you know, I've learned that what most captures my mind is the ways in which we try and fail to connect and care, and that there are many worlds or times, places I might want to write about that in, but that that's really what drives me and I didn't know that when I wrote the first book. When I wrote the first, I just wanted to write a novel, you know, and all the rest was going on subconsciously.

[00:26:25] Jack Wrighton: I love the idea of this sort of hard sci fi novel that keeps morphing to something else. Like, it's meant to be kind of big space guns and things like that, but actually it's like an exploration of how we connect and yeah. But, is there a sort of comfort in that? Because sort of the way you talk about it, you know, the kind of the experience of writing your first novel of you know, you wanted to write a novel, but sort of knowing yourself, does the process of starting a novel now feel a bit less fraught for you now?

[00:26:53] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I think if you care about anything, the stakes always feel very high and I think I definitely go through anxiety and think, will this be too similar to my last book? Oh no, will it be too different from my last book? You know, what will people say? But I think what is quite freeing is, I think, I don't think I'm alone in this.

There's a feeling I think with your first novel that's your only chance and you have to say everything that's ever been important to you and every the most beautiful thoughts you've ever had and you have to put them all in this one book. This one book is your one shot and I think that is one way of writing, and, you know, reading other people's debuts of, you know, it's possible to have clarity on your own.

I think sometimes that creates amazing work, but I think as you keep writing, it's possible, I think, a little bit for your ego to step aside and to say, how can I most be within the world of this book? What do these characters need? Yes, that other thing is interesting to me, but it doesn't have to be in this book and you can sort of play with the weights you put on things. So, for example, Kit's mother is half Japanese and there are some thoughts about that within the book, it's perhaps a little bit why her family are so isolated is her mother is half Japanese, half British, and her dad's American, and they live in this British coastal town where none of them are from, and they're not holidaymakers, but they're not locals, and it means that there's not so much of a community to reach out to and so it does have this big effect on what's happening. But I didn't feel like this is my big multiracial novel. I didn't like that, that it was absolutely important, absolutely not incidental, but that I didn't need to say everything I've ever wanted to say about being mixed race in this book, that I could say the things that this particular book needed. Does that make sense?

[00:28:53] Jack Wrighton: That does make sense, yeah, and in terms of you seeing your book, you know, on a shelf in a bookshop, for you these days, you know, do you still have kind of time to read for yourself or is a lot of your time kind of taken up with writing? And I know you sort of teach as well and tutor.

[00:29:10] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I think it's very important to me as a writer, but also as a human, to read, that doesn't mean there aren't times where I feel very pressed, but I think when you read something excellent, it makes you up your game as a writer. You're not, you're not necessarily going to copy that person or do exactly what that person did, but seeing the mechanics of their work, being surprised, they're like, Oh, books can do this too. It just, it makes you write better. I really, I absolutely believe that and so there have been periods in my life where I haven't been able to read either due to what was going on or due to mental health stuff and they're what I think of as some of the worst times.

So I'm not saying, That if you were listening to this and you don't have time to read at the moment that that makes you a bad person or not able to be a writer. You know, we all have things that happen, but I hate it. I hate it when that happens and so it, as soon as I'm able to life wise brain wise, I'm trying to read again always and so yeah, I'm still reading. It's basically what we'll say. But what I would say about teaching is that I think it helps me read. It doesn't feel Like, Oh, this is my awful work reading and then this is my joyful reading for pleasure and that applies both the student work and to the work that I read to prepare for class.

So, you know, reading a student's work, I can be surprised and moved in the same way, but equally, when I'm preparing pieces that I think will inspire my students, I have to think, well, why did that inspire me? What about this is working and how is it working? And why do I think it's beautiful? How do I articulate that so that someone else can see it?

I think all of that helps me as a human and a writer, and you, I think, asked me to recommend a book that I would read at the moment, and I mentioned a series called Reverse Engineering by Scratchbooks, and I bought them because I thought there were two, I think of two at the moment, I bought them because I thought they would help me teach, because what they are is they have a short story, I think they've all been published elsewhere first, and then they have an interview with the writer of that story about the story and about how they wrote the story and, you know, maybe this will sound like nerdy and craft practitionery, but I think even if you weren't intending to necessarily go out and write a short story immediately after reading it, there is, I think for anyone listening to this podcast who's interested in process and writing, there's something really wonderful about it and because it's so specific, it's about that particular story. So there is a Chris Powers story in which he talks about a walk he went on with his wife that he then set the story on that walk, but with two very different characters and about the way in which he observed the environment on that walk, but then what he looked up later and what he chose to include and not include. And you can really get an insight into how that story was built and I just, I think it's a wonderful series and I tell everyone I can about it because I want them to keep putting out more. So I want to nosily look into all these brilliant writers' minds.

[00:32:38] Jack Wrighton: This is, yeah, this is now just, a public encouragement of, yeah, reverse engineered books to do more. But, I mean, there's certainly a wide interest out there, you know, something. Working in a bookshop, which is quite evident, is, you know, many people who read also harbor, even if as a very sort of deep secret, a desire to, you know, write themselves or express themselves through the written word.

We even have people coming in, you know, asking for advice, and we have to say we're booksellers, you know, we can help you with certain things, but, you know, there's a whole sort of world involved in writing a book, and, something like that, you know, sounds so sort of educational, a great way of, as you say, sort of seeing what's possible, because I think a lot of people start feeling like, oh, well, I thought about writing this, but no one would read that.

[00:33:29] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I think it's also great because I think it can be super helpful to say this is what a five act structure looks like, this is how you create plot tension, but I think especially for people who are new to their writing journeys, those rules can sometimes feel like rules and like very oppressive and as if their story won't work unless it fits this exact structure and I think that that can be quite squashing. Whereas instead, looking at, you know, they have Eun Lee, they have Sarah Hall's story, the very different writers talk about their process, that you see that, oh, there are multiple ways I can address this. There are multiple ways into a story and I think that can help those people who do want a little bit of a guidance, a little bit of a pointing out craft wise, but who might feel like, oh, if I don't follow one of those models of like, how to write a bestseller in 90 days, you know, then my work isn't worth it and I mean, you know, if one man just wrote a bestseller in 90 days, I say, congratulations to you, go have a party.

But I think that model of writing is one I think a lot of people find unhelpful rather than helpful and I think just seeing different people's approaches and feeling like you have the freedom to choose. I think it's a little bit better.

[00:35:02] Jack Wrighton: Can be massively helpful. And in terms of one of the other questions we asked, which I always feel a bit mean for asking, and it's a kind of all time favourite book, or a book that has sort of stayed with you throughout your life.

[00:35:16] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: So I'm going to stick with the answer I gave you, even though part of me is like, oh, should I have said something else now? And I think I cheated slightly because I gave the answer to a book that I was thinking about as I was writing Sleepwatcher. So I felt like, okay, I could talk about this, but it's genuinely a book I love, which is The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson and that has recently been made into a bunch of TV or Netflix, and I think I watched five minutes and it upset me because it wasn't my version of the book. So I was like, away, away with you! And it's a story that's conventionally understood as being a horror story. There's a haunted house which is creepy and where there are sort of supernatural phenomena and a bunch of, there's a guy who's supposedly sort of a scientist experimenting on it and then he reaches out to people who've been sensitive to such phenomena and they all come to the house.

But what I love about it is that I'm not sure the house is horrible. I think it's dangerous and things happen, but I think it very much feels like it reaches to something in the characters and there's a moment that I'm not alone in loving where one of the characters is on her way and she stops in a restaurant and she hears a little girl having an argument with her parents, and the little girl doesn't want to drink her, I think it's milk, I'm not sure, milk or water, doesn't want to drink and her parents are sort of yelling at her, and the little girl saying she only wants to drink from the cup with stars on, and you, or her star cup, and you realize that practically what this girl is saying is that, at home, she has a cup, it probably has stars on, she's a toddler, she doesn't want to drink from this foreign cup, I don't, you know, anyone who spends time with small children will recognise this moment. But the character... Listening to this, things don't compromise, don't ever compromise, don't let them make you drink from these boring cups. Hold out for the star cup, hold out for the beauty, and this is a character who herself has found her life very unbeautiful, who's quite shy and feels like an outsider, and, you know, even before she gets to this haunted house, you know, she has been through a lot and anyway, I think it's such an insightful novel. It's a suspenseful novel, but to me, it doesn't matter what's causing the house to feel haunted in that, you know, there's always a sense of, is this just in their heads? Is this real? But like, that it is real to them and it's real to them for perhaps a reason and you know is the haunting coming from the people who come to the house or is going to the house and it's a great look at being a person through this really fun creepy lens anyway so yes it's definitely a book that I've been happy that I got to read and reread in my life. So, I don't know, I think that's the most I could say for a fave..

[00:38:25] Jack Wrighton: No, that's, you've certainly sold it to me. I've always wanted to, I've only, shockingly ever read, feels bad when you're a bookseller and you admit all the books that you haven't read, because...

[00:38:36] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: There's only so much time!

[00:38:37] Jack Wrighton: I know, there is only so much time! Because I've read the classic short story, The Lottery, which obviously, I think, you know, a lot of people are familiar with and love that and I'm sort of fascinated with Shirley Jackson as, you know, just an individual as well. So I've always wanted to read The Haunting of Hill House and you have really sold it to me because I've heard about this kind of, the great sort of characters within it.

[00:38:59] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I mean, also, we've always lived in the castle. Also great, also brilliant. So, you know, if, depending on which one appeals to you more.

[00:39:08] Jack Wrighton: There's, yeah, there's multiple, multiple options, and you say the house isn't bad. I think you said, you know, that it's just sort of connecting with these people. Do you sort of try and move away from the kind of, obviously, villainous and kind of looking at the complexity of things, because reading The Sleep Watcher, that's something that stuck out for me is that, again, without giving too much away, there's behaviors in this which are, you know, quite shocking when we come across them, but nothing villainous. I don't know if that's fair to say that because we're seeing it through Kit's eyes. We're seeing everything through kind of love and her love for the people around her, you know, there's a lot of grey. There's no sort of, you know, clearly, these are the good people. These are the bad people.

[00:39:53] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Yeah, and I think that's something that I've always been interested in. I think, you know, if it was so simple that we could point out, these are the goodies and these are the baddies and, you know, life would be very easy and, you know, we...

[00:40:07] Jack Wrighton: It would yeah.

[00:40:07] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: But, you know, okay, there are people in the news where I read about them and I think maybe you are just a straightforward baddie, I don't know, but of the people that I have met in person in my life, I've had actual conversations with, I have met people who've done some not great things, but I haven't met anybody who I think is a straightforwardly, they're just out there trying to be a baddie, trying to make the world the worst place. I've never met anyone like that and yet, we collide with each other and yet we struggle to know what to do with each other and I think that was so important to me and it's not a spoiler to say that Kit finds out her father isn't quite the man she thought she was because she finds out fairly early in the book.

But she doesn't know what to do with that information and she in part doesn't want to know it and she tries to find her way around it. She tries to find her way through it and I think that came from the fact that the people I know who've had someone, many of the people I know who had someone who in their life was violent, they would say, Oh, my life wasn't in danger, you know, I don't think they're trying. I mean, there are all these justifications, but they don't undo, it doesn't undo the harm and yet they can also see that that person loves music, or has done this very kind thing the other day that's genuinely a real thing and I think that is what makes it hard to leave. That is what makes it hard to make boundaries, that you can see all the beauty in that person as well as all the damage and I think that is something that is very important to me in my fiction because I think, and I don't want to sound over the top, but I truly think it is, it's dangerous to start thinking about people in terms of the goodies and the baddies and if we do that in our art, then it tempts us to do it in our lives and when we simplify people, it then becomes acceptable to treat them as if they weren't human and that is a very dangerous path to me and so I don't want to, I'm not saying that, you know, we all need to read complicated sad books. There are other ways too. But I think, for me, that is an important way to show people or to talk about people.

[00:42:39] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, absolutely, and I think. you know, I understand that, you know, when a writer such as yourself goes out to write a book like this, you're not sort of, you know, looking to necessarily have, you know, we'll have a big conversation and then we'll sort out what the issue is at the heart of this book, you know, I understand that isn't how it happens, but you sort of talking about seeing people just as kind of the good guys and the sort of bad guys can lead to sort of, you know, not seeing the fully human, you know, if we are to find a kind of a way of living sort of more harmoniously with each other, I suppose, you know, a kind of, you can't then see things in kind of black and white. There has to be an exploration of the grey within kind of the art world in general. I don't know if that's fair to say.

[00:43:21] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Yeah, I think so at least. But yeah, which is it, which is to say we can't, you know, also enjoy things with very straightforward heroes and villains. I just think we shouldn't only enjoy those.

[00:43:31] Jack Wrighton: Yes, yeah, absolutely, and I'm aware, sorry, that we've, you know, we've talked about the book, but at no point there's been a sort of sum up of it for the listeners who are, you know, coming across, The Sleep Watcher for the first time. Would you mind giving a sort of a brief overview for those who are interested in picking the novel up?

[00:43:48] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: So the sleep watcher is told as a confession from Kit to her lover because they are maybe going to live together, but Kit says you need to know this thing about me first and what she confesses is that when she was a teenager living in a seaside town, she began to have these out of body experiences and witnessed things happening within her town and within her family that she didn't want to know and that caused her to do something terrible and so that's the sort of pitch for the book, if you will and if you do, dear listeners, read it, I hope you enjoy it.

[00:44:27] Jack Wrighton: I'm sure they will, and I always like to end the podcast with a reading from the book to hear from the author themselves and from the book itself. So if you wouldn't mind, we'd love to hear some of The Sea Watcher.

[00:44:39] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: So I thought I would just read from the beginning as it's the simplest and I'm going to read through the first chapter, which is only two pages long. Some of the other chapters are longer, but hopefully you'll have patience for these two pages. So, The Sleep Watcher.

I have never returned to the town. I rarely say its name, only that I grew up a few hours from London. I left before I turned seventeen. All along the coast, there are gate towns. Ramsgate, Margate, Sandgate, Westgate on Sea. These are openings in the high, hard cliffs of this island. Gates to the water or to the land, depending on your perspective. Then there are the raised headlands, Beachy Head, Mine Head, Portis Head. These offer the gifts of sight. Our town was neither a head nor a gate. It was a ripple. The town bent towards the sea before rising up again cliffwards. Our cliffs were not famous, and their sides were lumpy and jagged. Tide markers raised their bald heads along our streets. There were three churches, one of which had been converted into a cafe.

The local paper bemoaned arsons by suspected youths, but otherwise crime was low. The sea is now a train ride away, but sometimes I see a gull making its white bellied way through the air to pilfer from our bins, or perform some other bastard behavior. Yesterday I saw two. One swooping after the other. In brutality or romance? I told myself I would tell you what happened in that town. I started wrong. Do you remember? It was while we were making dinner at your flat. Your knife shuttled through the onion. You were blinking back acid tears. Maybe I felt braver because you weren't looking at me. I mentioned the town and added, almost casually, do you know, while I was living there, I stopped dreaming. Who can blame you for the reply? Other people's dreams are always boring. I didn't argue that this was not a dream, but an absence. Instead, I gathered onion peel, sweeping the husk into my hand. I have to try again. It wouldn't be fair to wind myself around your life before I tell you what happened in that place.

It's not a thing I have perspective on, even 12 years later. The memories are salty and humid. Perhaps you'll say, I was barely out of childhood, and that my mistakes were understandable. I hope that afterwards you will still want to pack your stuff for me to box mine, and for us to conjoin our lives. Or maybe, you'll never be able to knot your fingers around mine, because when you see my hands, you'll remember the damage they've done. You'll decide, I'm not the sort of person you want to live with after all. While you have no time for dreams, you've always had time for books. Whenever I borrow one from your shelves, I trace the graphite underlinings and marvel at your careful attention and the luck of your students.

So I thought I'd try to write you one, or something like one anyway. An account with a beginning, a middle, an end. Perhaps not everything is quite accurate. There is no one I could check with. I am almost sure that I have not made anyone kinder or crueler than they were. Although it was long ago, I remember that year more clearly than I do last month.

[00:48:07] Jack Wrighton: Wonderful. Thank you so much for that reading, Rowan. That's unfortunately brought us to the end of our conversation. Thank you so much, and for those out there, The Sleep Watcher is out now. It's available at Mostly Books in our shop online or at your local bookshop. Rowan, thank you so much for joining us on Mostly Books Meets.

[00:48:25] Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Thank you so much for having me. This has been such a lovely conversation. It's so fun to talk about other people's work and why I read, so thank you.

[00:48:37] Jack Wrighton: Mostly Books Meets is presented and produced by the bookselling team at Mostly Books, an award winning bookshop located in Abingdon, Oxfordshire. All of the titles mentioned in this episode are available through our shop or your preferred local independent.

If you enjoyed this episode, be sure to check out our previous guests, which include some of the most exciting voices in the world of books. Thanks for listening and happy reading.