Thank you for listening to the The Book Love Foundation Podcast. If you enjoyed listening, please share it with a colleague or two.

Creators and Guests

What is The Book Love Foundation Podcast?

Celebrate the joy of reading with the Book Love Foundation podcast. This is a show filled with information and inspiration from teachers and leaders across grade levels, states, and school systems. We interviewed authors and educators for the first five years and now turn our attention to leaders in public, private, and charter schools. Find out more at booklovefoundation.org or join our book-love-community.mn.co of 2500 educators from 28 countries. We sustain joy together, one kid and one book at a time.

Penny Kittle 0:00

The book Love foundation podcast is produced by the teacher learning sessions, connecting teachers with ideas, experts and each other.

Kylene Beers 0:16

if a reader is willing to share any amount of time with the ideas that I put in a book, or that Bob Probst and I, when we're writing together, put into a book, then I want those moments to not only be educational, but I want them to be quiet moments that feel like a conversation.

Penny Kittle 0:47

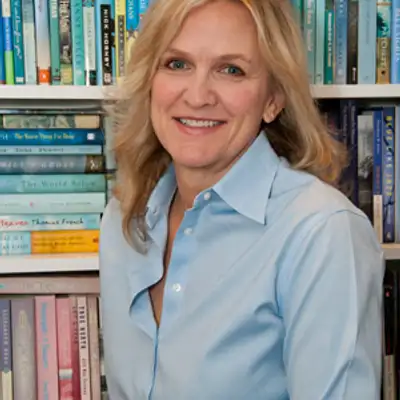

Welcome to the book Love foundation podcast. Welcome back. I'm Penny Kittle and I'm your host. This podcast was created to bring you close to teachers extraordinary middle and high school teachers who have won grants of books for their classroom libraries. From the book Love foundation. I love listening to teachers talk about their work, but today's podcast is different. Today we will think deeply about the teaching of reading by listening to an all around superhero Kylene Beers. Our conversation is long, so we are bringing it to you in two parts, one today and one tomorrow. Kylene Beers, warm Texas energy. Kylene Beers, she's generous. She's determined. She is true. She's the bring the house down. This, I believe, keynote at New England reading last fall, and she's the I Am, not an H Facebook post that reached 1000s in an afternoon. Kylene Beers will change the way you think in one conversation and then guide you to sharpen that thinking year after year as you reread her posts and articles and books,

Penny Kittle 2:00

Kylene Beers serves as the senior reading advisor to secondary schools for the reading and writing project at Teachers College Columbia University. Previously, she was the senior reading researcher at the comer school development program at Yale. Kylene Beers was president of NCTE. Received nctes Exemplary Leadership Award from the conference on English leadership, and was chair of the National adolescent literacy coalition. She is all that seriously. I get nervous talking to this woman. She knows so much about everything and is so thorough in her research and her thinking that when I spend time with Kylene, she makes me want to work harder and understand reading better. I know with Kyle's guidance, I will reach more of my students this year, and every year, I'm excited to share my conversation with Kylene Beers on our podcast today. So excited Joining me to talk more about that is Kevin Carlson from the teacher learning sessions.

Moderator 3:05

As Penny said her conversation with Kylene will be presented in two separate episodes, this one and one that will come out tomorrow to make sure you don't miss it. Please subscribe to the book Love foundation podcast in iTunes. Do it today.

Moderator 3:21

Also a transcript of these episodes will be available to people on our email list. We will send a link to your inbox, and you can read along as you listen, pause the podcast and reread. Dive deep with a slow reading. Add the transcript to your stash of resources to keep for future reference, whatever you like. We'll have details for how to do that in a bit, but now part one of Penny's conversation with Kylene Beers.

Penny Kittle 3:50

Good to talk to you. Thanks for taking some time.

Kylene Beers 3:53

Absolutely excited to be a part of your project.

Penny Kittle 3:56

Well, I am interested in talking a little bit about when kids can't read, what teachers can do. I was I was thinking about this book, because I remember when I was teaching eighth grade, and I first read it, and I was so moved by all of the wise things you had to say about reaching kids that were sitting right in front of my classroom.

Penny Kittle 4:18

So I'm wondering if you could summarize some of the big ideas in it, just because I know not everyone has read it.

Kylene Beers 4:25

and it is a big idea book. I'm glad you put it that way. When kids can't read, was really my effort to look closely at what it is I didn't know how to do when I was a beginning teacher. I'm a secondary certified English teacher. That means in Texas, when I was getting my degree, that I had coursework in literature and in composition and in grammar, but no courses, no courses in. How to teach a child to read. So when I headed off into my first job, which was in a middle school, and was confronted with children who did not know how to either make sense of the words that they could accurately decode or not even decode words. I really had no strategies that would help me help them. So I used to I talked louder and I talked slower. Those strategies actually weren't very helpful to anyone, and eventually I began a journey that actually continues to today to help me understand what to do when kids can't read, when I finally felt like I had enough information, I sat down and I literally wrote the book that I thought would have been helpful to me. So it covers a variety of issues. It talks about, what do you do with that older kid who is having trouble decoding multi syllable words? How do we help improve vocabulary? It even pushes into spelling, because there is a great relationship between spelling, writing and reading. It looks at engagement. It looks at how we help kids make inferences. I'm particularly fond of the section that really offers fix up strategies so that when kids are stuck, they have some tools to turn to and not and those tools don't always have to be standing in front of the teacher, saying, I don't know what to do. And then, of course, the body of the book deals with comprehension.

Penny Kittle 6:47

Yeah, I remember carrying it around with little post its in all these different spots that helped me. But what lingers still are the letters at the end of each chapter.

Kylene Beers 6:58

You know those letters to George had they got written long before the book did. Actually, I had come across a journal that I had kept that first year of teaching, and this was, you know, long before I knew anything about ethnography. Had never heard the term anecdotal notes or running records. I just knew at the end of each day I needed a way to to take what I was feeling and what I was learning and put it in a safe place. And that safe place for me was a journal, and the kid who tugged on my heart that year was a little boy named George, and so I had, I would go home in the evening, and as as accurately as I could write the conversations that George and I had shared years later, we moved, my husband and I moved, and I came across that journal, And I began at that moment writing back to George, or maybe I was writing back to me. I'm not even sure. When I sat down to write the book, by that point, I had read enough professional text that I knew I wanted this one to do something I had not yet encountered in a professional text, which was develop a very intimate voice between me and the reader, and to me, that meant being as vulnerable with the reader as I could be, and the best way for me to be that vulnerable was to share Those letters to George,

Penny Kittle 8:41

I love how you said that. I think that's the heart of a good professional book, that relationship between the writer and the reader. And you do that so well,

Kylene Beers 8:52

well, and when we don't have that, I think that what we've done is create a distance that that teachers feel increasingly every day. I think teachers feel distance from parents. They feel distanced from policymakers. At times, I worry, because we give teachers so many students that they even feel distanced from their students. So if a reader is willing to share any amount of time with the ideas that I put in a book, or that Bob Probst and I, when we're writing together, put into a book, then I want those moments to not only be educational, but I want them to be quiet moments that feel like a conversation.

Penny Kittle 9:49

You do that well.

Kylene Beers 9:50

Thank you.

Penny Kittle 9:52

Now I'm curious, how many years ago did you write that book?

Kylene Beers 9:56

You know, I got a note from Heinemann. Think two. Years ago. And I think they told me two years ago it was 12 years. So I think we're coming up on 15 years. You would think that you might know the birth date of a important child like that a little better, but I don't.

Penny Kittle 10:14

And what if you could go back and revise or write a second edition? Is there anything you'd change?

Kylene Beers 10:20

We talk about doing that. We being the Hyman folks and and me, and occasionally I'll talk about it with teachers. And so I've given that some thought. I think people expect me to say, Oh, well now since you know we're in the 21st Century that I would or deep into it, that I would add a chapter on technology and that perhaps I would add a chapter on working with English language learners. The answer to both of those is, no, I wouldn't. I'm not a I'm not sure the go to person for technology, and I'm not an expert in working with English language learners, and I think readers deserve writing that reflects expertise. I do think that what I would do is add more information on the homeschool connection. And I think I would take the two chapters that currently exist on talking about engagement and building interest, and probably push those into three or four chapters, I think I did not give that part of reading the attention that I would give it today.

Penny Kittle 11:35

Yeah, I wonder if that hunch of yours has a little to do with how hard we all feel it is to engage kids today.

Kylene Beers 11:44

It might be and it's it's not only that it's hard to engage kids, but I think I want to address, how do you respectfully and politely tell the voices that are suggesting that we should not read entire works of literature with students, that we should only read passages with students, or the converse, that we should spend three months reading one book with students. Are are both ideas that need to be challenged, and I really would like probably to take the time and the space in a book to help teachers who are under the pressure to do what the policymaker says to do, have the tools to have the conversation at the school level to change those really bad decisions.

Penny Kittle 12:42

We could use your voice in that.

Kylene Beers 12:45

We need lots of voices in that one, lots of voices.

Penny Kittle 12:48

That's so true. So now we have these two amazing books, notice a note and the reading nonfiction, notice and note stances. And I, you know, I know that when notice a note came out, what I held on to was that I do, of course, so much independent reading and conferring in my classroom, but you were giving me ways to talk about all of these different books in one lens. And it's been so valuable to be able to say to kids, and to hear my colleagues say to kids, oh, that's again and again, and know that we're creating this kind of a lifeline between reading experiences across grade levels.

Kylene Beers 13:27

Wow, that's That's great. That's a wonderful compliment. Penny. Thank you.

Penny Kittle 13:32

Well, talk to me about how the book came to be.

Kylene Beers 13:36

You know that book really happened. The idea for the book happened after a lesson Bob and I had been teaching. We were visiting with a school. They had asked us to come in and teach a lesson in a literature class, and the teacher had sent to us a short essay. This was a high school, and it was particularly complex essay and and she said, you know, my kids just have really difficult moments trying to understand a text. I'd really like to see how you help them. So we prepared the lesson. Went in. Bob did most of the teaching. And if you've never had the opportunity to really study how Bob Probst crafts questions and then puts them in an order that leads people to amazing ahas. I would encourage you to spend some time looking at some of his landmark texts, especially response and analysis, a personal favorite. Well, it, you know, it should be for all of us who are English teachers. And so I watched him, and he really did help these kids move from barely any sort of response, you know, I think. The longest response was the child that said Idk. And of course, it took me a while to figure out what that idk is actually the verbalized idk that we see on a text to actually having answers that showed insight. And so we left the class and I told Bob that he had done a great job, and he was appreciative. And then I asked him, I said, Do you think those kids will be able to do tomorrow with a new text? What you help them do today with this text? And he said, I don't think they can do it at all. And I agreed with him, and we both realized at that moment that all of our careful crafting of questions was actually working against our ultimate goal as teachers, which was to Create critical, independent, lifelong readers. And yet, every single time we stayed in charge of asking the questions, we were eliminating one of the most valuable parts of reading, which is that ability to ask of yourself important questions about what you're reading, and that really led us to simply wonder, what was there in a text that appeared across virtually all texts, literary text that was obvious enough in the text that we could show kids who are surface level readers how to notice those elements and then just reflect on them for a moment to help them begin to go beneath The surface of the book, and of course, the research. It began a little bit with that question, but then it moved quickly to asking about 3000 teachers grades four through 10, what were the books they most often taught in their classroom. Now we realized if a teacher only used readers workshop that never had a common shared text, those teachers weren't responding. We were really looking for the teacher who says, Yes, I bring kids together, and occasionally we read a text in common. It was one, oh gosh, Penny. It was one of the more silly questions we've ever asked, because it was open ended. So we now have 3000 people responding, some of them with up to 15 books. And as all of this data came in, I looked at Bob and I said, I wonder if either of us ever wondered how we were going to sort all this information. Because, as you know, if you're really busy responding to a survey, you don't always check the spelling of a title. You don't know if you want to, if it's the something, does the do you want the at the beginning, or do you want to put it at the end? And people misspelled words. And so after we finally got this huge body of titles, put in some sort of system that we could see what we had. We took the top 100 books that were mentioned again, grades four through 10, and I mean per grade, grade 456789, 10, put that list back out in the field. Had about 3500 responses this time. And what we asked teachers to tell us was, which of the titles do you most often share with kids that gave us a much more workable number? And from that, we just began reading all of the books, looking to see if we found something that would help kids understand character development, plot development, symbolism, conflict resolution or theme and slowly, those began to emerge. Eventually, we identified 13 signposts, and we were in Jenna Choi's classroom in Harlem, teaching her kids, her eighth graders, the 13 signposts. And at that point she, at one point in the lesson, she interrupted us and said, boys and girls, I need to take Mrs. Beers and Mr. Probst into the hall and Penny. I don't care how. How old you are when the teacher takes you in the hall, you are in trouble. We stand out in the hall, and she looked at us and said, seriously, 13 signposts. My students have trouble remembering to bring their pencil to class. And she was right. Of course, 13 was way too many. So we started pulling back and pulling back, and eventually settled on the six signposts that not only occurred in the majority of books, but occur often within a single book. And then to each signpost, we addressed one anchor question so that kids could do what we thought was most important, which was question the text on their own. And then we sent those out to about 450 teachers who began teaching the lessons for us, and sometimes with us, and that let us create the lessons that are actually in the text itself.

Penny Kittle 21:07

Wow, what a process.

Kylene Beers 21:09

It was a multi year process, and it was it was grounded in research, it was directed by research, and it was highly informed by classroom teachers who, you know, we don't choose a very special kind of teacher to work with us. We choose any teacher who's willing to say, I'll give it a try. And that meant we had first year teachers. And, you know, 30 year plus teachers helping us. We had teachers who worked with special education students and teachers who worked with AP students. We had everyone offering their time to us and and that felt like the biggest gift of all. We weren't writing this in isolation. We weren't coming up with an idea and hoped it helped. We were refining it in our nation's classrooms for about two years, and that made the critical difference.

Penny Kittle 22:17

It's you know? It's why it all hangs together so well. It's why you have hundreds of teachers on Facebook offering help to each other and posting things they're trying.

Kylene Beers 22:27

Isn't that page you're referencing the notice and note book club page, which was started by Allison Jackson, a third grade teacher who asked, Did we mind if she started a page where elementary teachers could talk about the book, which we certainly wanted her to do. Bob and I don't pretend to be elementary teachers, we made reference to what elementary teachers had told us in that book, but we knew there needed to be a more robust conversation about how this looks in kindergarten, first, second, third, fourth, fifth, grades. And of course, once Allison started the page, it just blew up. Now, now there's right about 10,000 teachers who every day go there, and just like you said, they ask questions? They answer questions, they share work, they share ideas, they share frustrations, and most of the time, they answer each other. Occasionally, Bob and I will pop in if we see something that that we think, gosh, we wish we could be part of that smart conversation.

Penny Kittle 23:41

You know, that is such a gift to teachers all on its own. You know, I know they're reading the book as well, but it's those practical things, when you try it, what Tom Romano calls the messiness of teaching that teachers want to continue to have conversations about. So there it is, right. There. 10,000 people want that conversation.

Kylene Beers 23:59

You know, we had a teacher, oh months ago, who said, my second graders, first graders, I forget, have trouble remembering the individual anchor question that is attached to each signpost. And she said, I just asked my kids for all of the signposts to think about, how will this change things? And I looked at the clarity of that question, and I thought, well, of course, of course. So every place we go now we pull up that little conversation that happened on Facebook and said, This is what it means to constantly revise your understanding of a situation. This one teacher said, This is what works for her kids, but it resonated with us, and so we share that, that strong modification for elementary teachers every place we go.

Penny Kittle 24:59

Yeah. Yeah, I love that. It's almost like a co created work, you know, it exists in, you know, just the smart, wise thinking of both of you. Because, of course, Bob was one of the first people I read as a when I was getting my secondary certification, and had always thought of him as this wise leader that I would never meet, but would learn from. And now that I've spent time just sitting and listening to the both of you think over a glass of wine at the end of booth Bay, it's such a privilege to think with people who care so much for the work and care for kids, and at the center is independence. You know, teachers want to work themselves out of the job of leading those discussions and leading the thinking, and give kids the gift of becoming independent readers who you know always can turn to these strategies and things they know.

Kylene Beers 25:53

You know, I've always thought that the small conversations, or better said, the conversations in small groups that I get to be a part of from time to time make the biggest difference in my thinking whether, whether you're right, it might be you and Linda reef and Bob and me sitting around at the end of booth Bay, or It might be the group of teachers I was with a couple of days ago after the Dublin literacy conference, sitting there having a glass of wine that always seems to make its way into the conversation and, you know, really spending time sometimes on one small issue. And I think it is that moment of the particular that informs so much of what we do. But every single day, we are bombarded with the mass and getting down to the particular is difficult. Perhaps that's what great conversations allow us to do.

Moderator 27:06

We are going to pause here and wrap up part one of Penny's conversation with Kylene Beers. We will release Part Two tomorrow. You can get a transcript of this show of this conversation between Penny and Kylene delivered directly to your inbox by joining our email list. Here is how you do that. Go to teacher learning sessions.com/go/book, Love and use the sign up form there. It's that simple. If you are already on the email list First, thank you. And also check your email. You have received the transcript already, and that transcript includes both parts of the conversation, the one you just listened to, as well as the one that comes out tomorrow.

Penny Kittle 27:53

Thank you for listening to this episode of the book Love foundation podcast. The book Love Foundation is a nonprofit, 501 3c dedicated to putting books into the hands of teachers who nurture the individual reading lives of their middle and high school students. We have given away $100,000 in three years, and are currently reviewing 140 new applications for 2016 we wish we had the money to give to every one of these deserving teachers. If you can help us in that mission, visit booklovefoundation.org, and make a donation. 100% of what you give goes to books. Thank you so much for listening. Today. I'm Penny Kittle.

Moderator 28:34

Next time part two of Penny's conversation with Kylene Beers,

Kylene Beers 28:39

we want kids to recognize that nonfiction is purported truth. The author purports to offer you something that is true. And you have a job, dear reader, you have a job. It's a critical job, and it's to decide if that truth actually rings true for you.

Moderator 29:04

That's next time on the book Love foundation podcast. The book Love foundation podcast is produced by the teacher learning sessions, connecting teachers with ideas, experts and each other. You