Purchase Great and Horrible News

(0:27) Introduction

(2:05) Childhood reading habits

(19:08) Blessin's catalyst for writing

(25:54) Inspiration behind Great and Horrible News

(32:44) Old crimes and modern problems

(36:55) Recent reading

(41:56) Great and Horrible News

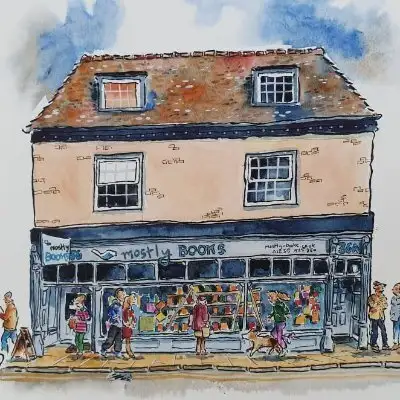

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a weekly podcast by the independent award-winning bookshop, Mostly Books. Nestled in the Oxfordshire town of Abingdon-on-Thames, Mostly Books has been spreading the joy of reading for fifteen years. Whether it’s a book, gift, or card you need the Mostly Books team is always on hand to help. Visit our website.

Meet the host:

Jack Wrighton is a bookseller and social media manager at Mostly Books. His hobbies include photography and buying books at a quicker rate than he can read them.

Connect with Jack on Instagram

Great and Horrible News is published in the UK by Harper Collins

Books mentioned in this episode include:

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck - ISBN: 9780241620236

Appointment in Bath by Mimi Matthews - ISBN: 9781736080269

The Grand Sophy by Georgette Heyer - ISBN: 9780099585541

Redwall by Brian Jaques - ISBN: 9780099595182

Creators and Guests

What is Mostly Books Meets...?

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a podcast by the independent bookshop, Mostly Books. Booksellers from an award-winning indie bookshop chatting books and how they have shaped people's lives, with a whole bunch of people from the world of publishing - authors, poets, journalists and many more. Join us for the journey.

[00:00:00] Jack Wrighton: Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, the weekly podcast for the incurably bookish. We will be talking to authors and creatives from across the world of publishing and discussing the books they have loved. Looking for a recommendation? Then look no further. Head to your favourite cosy spot and let us pick out your next favourite book.

It is my great pleasure to welcome onto the podcast this week writer and academic Blessin Adams. Blessin's book Great and Horrible News was published on the 30th of March this year. It is a wonderful exploration of murder and violent death in the early modern period, told through the lives of the ordinary people that experienced it. It is a hugely engrossing and often touching read, which marks a brilliant new voice in non fiction. Blessin, welcome to Mostly Books Meets.

[00:00:55] Blessin Adams: Thanks ever so much for having me.

[00:00:56] Jack Wrighton: Absolute pleasure, and in our podcast, Bless, we like to sort of take the author back to their childhood and learn a bit more about them, about the books that have shaped them. So, where did you grow up? Where were you born?

[00:01:09] Blessin Adams: Well, I was actually born on the Isle of Sheppey, off the coast of Kent, but I have no memory of that place whatsoever. I moved to Norfolk with my family when I was three and I've lived in the small market town ever since. I've not really gone anywhere else, which sounds a bit dull, but I love it.

[00:01:27] Jack Wrighton: No, not at all, and it's a really lovely part of the country, I feel. It's, and certainly for someone interested in history, it feels distinctly steeped in history as well, and was that always an interest of yours? Were you always kind of interested in the local history or in history in general?

[00:01:45] Blessin Adams: Um, Surprisingly enough, it's something that I came to much later when I was a mature student at the university. Really was the first time I started to have any interest in reading historical texts and looking at the history of crime and the social history of people going through extraordinary events. But yeah, no, it's something I've come to quite recently in my life.

[00:02:05] Jack Wrighton: And when you were younger, as a child, were you much of a reader? Did you enjoy books? Or was that also something that sort of came later on?

[00:02:12] Blessin Adams: Yes, I was a reader. I mean, as a kid, we always had the staples around the house, things like Beatrix Potter and Roald Dahl, and I loved anything that was illustrated. I think I poured over the pictures more than I poured over the words. But yeah, I was thinking back onto the sort of things I used to read when I was younger.

And I remember being massively into a Series called Red Wall, which was all about mice in an abbey that would have epic battles and epic feasts, and both seemed to thrill me as a child. And then I suppose as I got a bit older, I remember me and my girlfriends at school really enjoying this series called Point Horror.

They were these very small pulpy. Horror books that you could read in an afternoon and we were crazy about them, and I remember that we used to swap them because I don't remember where my books came from when I was a kid. I had three sisters and I think the books would just appear in the house at some point or another when they bought them.

But I remember these books being wildly popular and we'd rush to school to try and swap them with our friends. So, quite an exciting thing where you could all share it together at school. It was it was quite fun.

[00:03:13] Jack Wrighton: And they were sort of, horror-y, were they? Sort of ghostly mystery stories?

[00:03:19] Blessin Adams: They were the strangest, weirdest, tropey, pulpy books you could read, and I always remember being quite mystified by them as well because they were usually by American authors and I was really puzzled by all these Americanisms. I didn't really understand anything about the American school system or the fashion or whatever they were talking about. So they were these sort of yeah, these mystery stories about, I don't know, a stalker is stalking a young girl at school or something or so. Yeah, they were quite gross.

[00:03:47] Jack Wrighton: Mmm. But it's interesting, isn't it? Because I think there's always those types of books, you know, I remember, you know, the Goosebumps books when I was younger, and even now, you know, the kind of, I suppose what you could say, sort of, children's horror as a genre is alive and thriving. There's always that kind of interest in...

The kind of the creepy, the otherworldly, or even the stories that aren't otherworldly, kind of true life horrors as well.

[00:04:13] Blessin Adams: Yes, my niece is hugely into the horrible history books, those weren't around when I was a kid. But I've been looking through some of hers and they're really gruesome and really, well, I think quite fun. But yeah she's absolutely fascinated by them and I think by the the quite gory and the grim aspects of history.

So yeah, I think you're right, I think kids are always drawn to these things and quite fascinated by them.

[00:04:36] Jack Wrighton: What do you think it is that's so appealing about these stories? Whether you're a child or an adult, why do you think we're sort of drawn to these kind of slightly sort of gruesome, macabre stories?

[00:04:49] Blessin Adams: Ways People are drawn to them because they're frightening. Just the very thought of something like that happening, and potentially happening to you, I think, is quite compelling and frightening at the same time. So I think that we are repelled and attracted to these sorts of stories simultaneously and it can be quite thrilling, I guess, much in the same way that you would find, I don't know, going on a rollercoaster or something, it's terrifying and thrilling at the same time. You don't know why you do it, why you scare yourself, but it must serve some purpose why people are attracted to these stories.

[00:05:21] Jack Wrighton: I suppose like a rollercoaster, it's kind of fear, but with the ultimate knowledge that you are. In that moment, safe. A rollercoaster, you know, I suppose is kind of giving the sense of falling. But there's always that knowledge that actually you're okay. You know, you're going to experience it, but it'll be fine and I wonder if these stories for us are kind of a way of, yeah, of doing that in a safe way.

[00:05:43] Blessin Adams: Yes, exploring these themes from quite a safe distance, and as well, sort of like the sorts of things we read about, like my niece reading The Horrible Histories and the sort of things that I write about, of murders and things like that, they are extraordinarily rare. They are unlikely to happen to you, but they do happen and I think that's quite fascinating as well. If you're reading about some princess or some queen getting beheaded in the early modern period, you're thinking, well, that's never going to happen to me, is it? But it did happen, and I think it's incredibly interesting.

[00:06:12] Jack Wrighton: Yes, I wonder if it feels like a self preservation thing that, you know, if we read about these stories in some weird way subconsciously, we feel like, well, now I'm prepared in case that ever happens to me, when of course, you know, the likelihood of suddenly becoming you know, a queen in the kind of You know, 1500s, it is unlikely, but I don't know.

[00:06:34] Blessin Adams: But you know, the thing is that the people that I write about they are mostly everyday people. People who would have been like me and you and they have these terrible and extraordinary things happen to them And it wrenches them out of their everyday life and plunges them into this nightmare situation Where sometimes they just have they have to act perhaps even without thinking just by instinct, and they're just pushing through to get by as best they can You know, I think that those are the sorts of stories that are quite compelling to read about as well, because it does remind you that, you know, even though it is rare and unusual, it can happen.

And I think it's I feel a lot of sympathy for the people that I'm writing about, a lot of pathos as well for the stories and the experiences that they've had. And I just think that it's a privilege and a, quite a frightening thing at the same time to, to delve into these stories.

[00:07:29] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely. It's why I thought, you know, which I realised might seem like a strange word to use, described it as touching. But I think it, you know, it is because you come across these people who, you know, they've maybe lost a loved one or that they found themselves legally in a position which is, you know, quite...

Tricky and maybe doesn't align with kind of what is actually the kind of morally good thing or, you know, or whatever. And, it's touching to see these people kind of navigate that because it really, it humanizes history, when history can seem like an abstract thing, but suddenly you think, oh no, these are people just like me, they just happened to live, you know, so many hundreds of years ago.

[00:08:13] Blessin Adams: Yes, that's something I found quite extraordinary as I was researching this book, was The thoughts and the actions of people three, four hundred years ago felt very familiar to me and the way that they were responding to these events, I couldn't help but think to myself, that's probably how I would respond to these events as well.

The early modern period is a fascinating period of history. because it is simultaneously so very different from our own. There were so many things happening in that particular period. You had the the belief in witches and devils and ghouls, but you also had the scientific revolution and the enlightenment just on your doorstep.

It could be very difficult sometimes for us to wrap our heads around the way people were thinking. You had public executions where you would have. Thousands and thousands of people turning up to, to cheer the death on the gallows or of people being burnt to death. And you can't even imagine what it would be like to show up to an event like that.

But then you read the testimony of somebody who has been the victim of a crime and the outpouring of grief and sentiment that you read in this particular document. It feels so familiar and it feels like something that would be. written today. So I find the period fascinating because there's lots of contradictions perhaps.

And in one moment I feel repulsed by the way that people act and behave. And the other, I feel myself incredibly attracted to the way that they act and behave. And yeah it's fascinating.

[00:09:42] Jack Wrighton: And it's interesting, isn't it? Because with things I always find when you read about public executions and, you know, people turning up kind of in their thousands to see these things, you know, I feel like, oh, goodness, it's amazing that people did that. But then sometimes I do find myself wondering, you know, if tomorrow there was a big kind of public case and a particularly sort of reviled villain.

was, you know, they said, oh, we've decided, you know, they're going to be executed publicly. I do feel there would be crowds, you know, it's easy to assume everyone in those crowds was going just to kind of be like, yes, I want to see some death. But I suppose some people might have gone in sympathy or for many other different reasons.

And I think to suggest that wouldn't happen now is, you know, naive, maybe.

[00:10:26] Blessin Adams: You're right. I think there was a whole range of motivations and emotions at play when people would be would go to an execution. I always have in my mind those images from movies set in the medieval period, in the early modern period. You'd always have that grandma at the front row who's cheering and she's eating a bit of bread or something.

She's yeah, hang him. And you have this image in your mind that everybody was there to have a really good time and they were really into it and that they were Sort of like morbidly. engaged with what was happening. But there was a lot of sympathy as well. Various accounts that I've read of people attending executions would describe people in the crowd weeping and you know, sighing and expressing a great deal of sympathy.

There was also an element of people there doing their civic duty as a citizen in the early modern period engaged in wanting to see justice done. It would have been your duty to turn out to be these executions. It doesn't mean you were there to have a good time. You could be there and display gravitas.

You could take it seriously as it was intended to be taken seriously. Yes, it was a theatrical display and people did cheer and cry out and weep, but there would also be people there just watching because it was their duty. So I think there was a whole different, a whole range of reasons why people would turn out to executions.

But that doesn't deny the fact that they were also incredibly popular. I mean, for the big executions, you could have tens of thousands of people turning out. Could you imagine the atmosphere at something like this? If you look at a stadium crowd, I mean, 15, 20, 000 people crammed into a stadium, and then you imagine that's... sort of people that might be turning out in the streets of London to watch an execution. You can't really imagine it. I read accounts of the rooftops and the church towers absolutely dripping with human bodies because they're just all trying to cram into every available space. Wouldn't it be amazing to like just hop into a time machine and go back and stand in that crowd and just look around?

Never mind the execution, just the atmosphere and the lead up to it would have been extraordinary. But then you've got this incredible, hard to imagine performance happening on stage in front of all these people. Very tightly orchestrated, very tightly managed performance put on by the state for the people, for the good of the people. Yeah, it's crazy. This is the sort of thing I find so interesting, which is why I like to read and write about

[00:12:47] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, absolutely, and I completely agree about the time machine thing. I think that almost constantly just to see, you know, the kind of the sensory experience of being there, and yes, because when, you know, reading your book, when you mentioned about the numbers that could turn up to these events, I was trying to imagine what that would look like in a cityscape or a townscape.

Because of course, in a stadium, it's designed so you can see everything. But of course, people would be going. you know, it would be bleeding into kind of nearby streets. So I'm like, well, how would, what's going on there? Would there be areas where you actually can't see the execution, but that doesn't matter.

You're kind of part of the crowd anyway. I don't know. I find it so...

[00:13:29] Blessin Adams: Yes. Yes. Like you're soaking up the energy. I mean, this is definitely something I think that was woven into the whole sort of like procession in the lead up to executions is that there will be a processional route that sometimes was quite circuitous. So that the person being dragged to their execution could be viewed by as many people as possible.

I don't think everybody could cram into the perfect viewing space. They would have been, you say, been lining the streets and the processional route as well. I mean, Tyburn. One of the primary sites of execution in the early modern period was about an hour outside of London. So, you know, you could have people following along the horse and cart as prisoners are being taken to the site of execution.

You would have had people coming along. You'd have had people there waiting. I mean, Tyburn was different because it was outside of the city.

[00:14:13] Jack Wrighton: Yeah.

[00:14:14] Blessin Adams: It was in sort of like a rural area. There was much more space for people to gather. But you're right. So one of the executions in my book takes place in Cheapside. Which was the broadest street in the City of London at the time. But as you say, it could only hold so many people. It must have been absolutely heaving.

[00:14:31] Jack Wrighton: Yes, and I loved the detail of you know, people who lived nearby could, you know, earn good money renting. their upper rooms so people with, you know, a bit more means to them could pay for, you know, a place to sit and kind of a nice clear view, maybe get some food. It feels bizarre, but somehow also familiar.

[00:14:54] Blessin Adams: Yes, there would have been almost like a day out at the stadium atmosphere, people selling food, people having picnics, booksellers selling pamphlets, almost like there would have been programs, I guess. These would have been things that would have detailed the life and crimes of the person or persons up for execution, much in the way that when you go to the and you get given a programme telling you the story of what you're about to witness.

There's some absolutely amazing academics out there who specialise in the theatre of execution and they really dig deep into just how theatrical these events were. I mean, it's mind boggling. I love it.

[00:15:31] Jack Wrighton: Yes. Yeah, and obviously, and that's evident in the book as well, and the many hours of research that must've gone into it. We will go back to the book shortly, but in terms of you were reading when you were younger and I'm right in saying, when you were younger, you weren't, you know, particularly sort of academic.

[00:15:49] Blessin Adams: Yes, I wasn't particularly exceptional at school. I didn't enjoy school. My GCSEs were all sort of like the D and F variety. Yeah, it just wasn't for me. I spent most of my sort of my younger sort of like my twenties, I didn't go to university. I worked retail jobs I worked in bookmakers I did various things like that.

So yes I wasn't particularly academic at all when I was younger. It just didn't appeal to me. I didn't enjoy it. I don't know why. I just, yeah, it's just I'd rather be doing something else. I'd rather be doing something practical. I'd rather be outside playing or I'd rather be working. So, yeah, funny now I've got a PhD, but...

[00:16:30] Jack Wrighton: Yes, that's interesting, isn't it, how life can take us in different directions, you know? Just on the podcast, I've met many people who, you know, at school, Oh, I didn't particularly like reading. I certainly wasn't very wordy. But, you know, then have later on realized actually, you know, telling stories or, you know, something is really important to them and they enjoy it and I think it's always good to talk about that because I think particularly when you're young, you can be given an idea of every decision you make now will affect the rest of your life. And, you know, of course that's true to a degree, but I think it is always good. I think particularly when you're talking about books, writing to show that actually.

You know, it's not just for people who at school were academically brilliant. At school, I was very average and had to kind of try quite hard to be average. You know, it didn't come easily. Whereas there's some people who seem to barely turn up and then got kind of good grades. And I think it's good. I think it's good to talk about that because it's good to show that, you know, books or academia or anything really isn't set in the early years. It can come, you know, later on.

[00:17:34] Blessin Adams: I absolutely agree and I can't sing the praises of the adult education that I went through enough. I very much felt like I was starting from scratch when I enrolled at Norwich City College. It was an access to higher education course. And they were teaching you how to write an essay for the first time and these sorts of things and I remember having to write something like a 400 word essay and thinking to myself, how many words?

[00:18:05] Jack Wrighton: Yeah. Yes.

[00:18:07] Blessin Adams: I can't write 400 words. Are you mad? And you know, it was absolutely wonderful, and as I was there, I It occurred to me in my adult years, I love this, I love learning, it's really interesting. You know, at that point I was nearly 30, so it was something that I came to very later on and I wonder what it was that was sort of like missing perhaps from school or from education when I was younger.

Was there something missing in me? Or was there something missing in the education system at the time when I went to school in the 90s? I don't know. But yeah, there's so many different routes to get where you're going. Not everybody has to be exceptional at school in order to do academic work later on in their life.

[00:18:48] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely, and I think, you know, I think school is a, the education system has a very particular way of doing things, which will suit some people, but people are different. You know, there's some people that, that won't suit, but that doesn't necessarily mean that, you know, that they don't have the capabilities and what, when you are enrolled at that, access to higher education. What was the kind of catalyst for that? What led you to that decision?

[00:19:11] Blessin Adams: So maybe I should roll back a little bit because in between. My various shop jobs and working in bookies and then enrolling to access to higher education. I was a police officer, not for long, only for a couple of years. I'd gotten to a point where I was working in a bookies and I thought to myself, am I going to be doing this for the rest of my life? And I really wanted to. career progression. I wanted to try and get a job where you could go up, but there wasn't really anything I could do without any qualifications. So I thought, well, I could join the army or maybe I could join the police, and I went along and I did you know, those army experience days and I went along and did sort of like those police recruitment things, and yeah, I ended up going into the police and it was, absolutely, probably the best and the worst job I've ever had, I guess I could describe it, it was some of the most extraordinary experiences of my life in that job and also some of the most upsetting and frightening experiences of my life as well.

But it got to a point where I wanted to get married and I was working these shift systems that meant that I almost never saw my fiancé and I was just thinking to myself, gosh, you know. Could this be the rest of my life working these exhausting shifts and never really seeing my husband? And so that was when I took the decision to leave the police and go into the Access to Higher Education course and it was quite a leap, and it was quite a difficult decision to make, because when you're a police officer, you've got a lot of responsibility. Many people are quite impressed by the job you have. A lot of my friends and family thought it was quite an impressive job. And when I announced that I was leaving, people were horrified.

It's like they were really upset and I couldn't help but feel like I had to apologize to everybody around me. I'm really sorry I've let you all down, but I'm not a police officer anymore. And it was quite difficult as well to go for a position where you do have a lot of authority and a lot of responsibility to being a student at a city college where people weren't even I remember walking into an office on one of my first days and I think it was one of the faculty staff or something was in there and I just made eye contact and said, oh, good morning, and he just looked at me with disgust and then just walked out the room and I thought to myself, oh, because I was used to working in an environment where you were courteous to your colleagues and then I suddenly find myself in an environment where you're not even really to be acknowledged.

So it's just that was quite a difficult move, but I enjoyed the study so much and I was so much happier. I got married, I was actually late starting my access course for two weeks because I was on my honeymoon. So it was really quick. I left the police. I got married immediately.

As soon as I got back from my honeymoon, I was jumping straight into the access course. So it was a really quick changeover from one to the other. But yeah, I automatically felt myself being able to breathe I was a lot happier doing, being a student and I don't know, it was just fascinating to me just being able to learn to do all these new things, it suited me much better than being in the police.

[00:22:15] Jack Wrighton: Yes. Yeah. It sounds like you really found some satisfaction in that studying and in that learning process.

[00:22:22] Blessin Adams: Oh, yes, absolutely, and I think that's the reason why I just sort of, I stuck with it for so long and going back to what we were talking about earlier about not being exceptional not being the best, again, as I was in the access to higher education, and then when I went to university as an undergraduate, I was very much middle of the road.

I wasn't, you know, the genius student in the class or anything like that, but that was fine. It's I think as long as you, you're dedicated and you put in the work and you're genuinely interested and passionate in, in the work that you're doing, I think that's sufficient. I don't think you have to be a genius in order to be a, you know, a really good academic you just have to be a hard worker sometimes.

[00:23:01] Jack Wrighton: Yes, yeah, hard worker and yeah and you know, just interested in what you do, I think seems to be the key ingredients there, and did you say, sorry, that for undergraduate that was English you did?

[00:23:14] Blessin Adams: Yes, I did English literature. It was a bit of a toss up because when I went to university, I didn't really know what I wanted to do. My husband said to me, well, what did you like doing at school? I was like, well, the only class I enjoyed at school was English. I remember my English teacher. reading us of Mice and Men and when she got to, you know, the dramatic climax of the book, she was in tears. And I just remember being really touched. I thought to myself she must've read this book so many times during the course her career, and every single time she's reading it to her class, it moves her to tears. And I just thought to myself, so she was the kind of teacher that just really got you into what you were doing.

It was the only decent grade I had at school. So I just thought to myself, well, I'll do English then. And I absolutely loved it. So I did English for my undergraduate. And then when I did my master's, I did medieval and early modern literature, which is what I was most interested in. So that, that rather large time period quite, quite a range of literary texts that I was looking at.

But I think it was during my master's when I really started to get interested in the early modern period. And it was a wonderful taught course and we learned a lot of practical skills that were, I think really vital for my being able to write this book. We were taught paleography, how to read ancient manuscripts.

These things can be really hard to read. The handwriting can be indecipherable sometimes. So it's just sort of like having these skills of being able to work with old manuscripts. How do you handle them? How do you access them in the archives? How do archive catalogues work? So it was this sort of the technical, busy side of academic research that was really brilliant on the the talkmasters at the UEA and that's where I learned a lot of the skills that I then went on to use to, to write Great and Horrible News.

[00:25:12] Jack Wrighton: Yes, because knowing how to sort of sort through the source materials must be very difficult because it's deciding what's kind of relevant. Is there ever a temptation as well to sort of go down a Early modern, you know, almost like a Wikipedia rabbit hole, but just with archive materials and then think to yourself, Why am I reading all this?

This has nothing to do with I, you know, and then you have to stop yourself, or...

[00:25:35] Blessin Adams: Exactly what I did, and that's strangely how I kind of fell about writing this book in the first place, is so during my PhD... I was writing my thesis, kind of a dry subject, on the notebooks of law students at the early of court. I was interested in what these law students were sort of like scribbling in the margins of their notebooks.

So, I spent a lot of time dripping around archives and law libraries, but being quite a morbid and curious person in my downtime, I Just hit the catalogs and I'd search for words such as murder because I just wanted to see I wanted to see what was there, you know, what fascinating things can I find? And I remember that I was at the record office in Norwich and I'd called up a box of coroner's inquest records, and I, no other reason, I just wanted to have a lazy afternoon flicking through this catalogue of violent and sudden death, which sounds quite strange, but that's kind of how I wanted to spend my afternoon and it's as I was flicking through these inquest records that I found the story of Elizabeth Balance, which is one of the chapters I write about in my book, and she was a young woman from Norwich who had suffered a miscarriage. And as I was flicking through this. Well, the first thing that impressed me was how incredibly thick it was compared to all the others and they're sort of like these folded pamphlets. And as I unfolded it, I found these pages and pages of witness depositions inside. I thought, this is unusual. The coroner's, as far as I'm concerned, The past 10 years of records I've been looking at haven't been going into this depth of detail in their investigations and as I was reading them they read very much they were conducting a criminal investigation into a murder and I thought, well, this is a miscarriage, not a murder, and as I started delving into this case and reading more about miscarriage in the early modern period, I learned about how it was essentially a criminal offense for women to miscarry or give birth if they were unmarried.

This absolutely fascinated me and I just thought to myself, I would love to write about this. I'd love to write about Elizabeth Balance. Here's her story tucked away in these coroner's inquest records in the Norwich archive. I don't know if anybody's looked at these at all since they were written, I don't know.

So I just thought I'd love to write about this. Of course at the time I was eyeball deep in my university studies and my academic work. So I had to wait until I was free from my academic obligations, but as soon as my PhD thesis was in, I immediately started writing the book. I don't even think I took more than a couple of weeks off from submitting my thesis to jumping on working Great and Horrible News. I was that excited and I was that ready to get working on the book. I was like, right, I'm free. Let's go, yeah.

[00:28:16] Jack Wrighton: I've done... Yes, because that story really stuck out to me as one of those big differences in terms of, you know, then and now, was just, you know, the idea of a miscarriage could be treated like a criminal... You know, a criminal offense and how awful that was as well, particularly in light of kind of unwed mothers and how they were treated compared to the fathers of these children who seemed to just, I mean, barely be mentioned at all, you know, they were free to kind of carry on their lives, you know, that story really stuck with me.

[00:28:49] Blessin Adams: Yes, it was very much a crime that was thought to be of the female sex, even though, as you say, it takes two to make a baby. And it was quite a depressing subject to research. You had so many young women, usually very young women, barely out of their teens, working in service. And they would... be vulnerable to sexual assault and rape by their masters and when, or if they became pregnant, they would then be cast out onto the streets and left to fend them for themselves. And as unmarried women, they would have been social outcasts. They would have been condemned as whores as bastard bearers. And so, so already at that point, their lives were ruined, absolutely ruined, and it was believed that they, of all people, were motivated to want to murder their babies, either to induce abortions which I don't go into detail. In this particular chapter, I wanted to focus on, on, on the miscarriage and stillbirth side of things. But yes, it was also very tragically that the young women out there were very dangerously putting themselves at risk by inducing these abortions using all sorts of gruesome and frightening methods. So that in itself is absolutely terrible and absolutely tragic. But women who went through with their pregnancies and gave birth to their children, they were expected to somehow support themselves, somehow support their children on nothing. They had no support. In the early modern period, as within the medieval period, it was vital for people to be involved in their communities. Family units and communities were the bedrock of society. If you were cast out from these, your life was over and you were at a very real risk of starving to death, that you had no way to make a living.

So yes these women were in desperate situations. So if they were found to have given birth to a child and that child was dead, be it miscarriage or stillbirth, it was just presumed, well, they obviously killed the child, and so, that's really where the the 1624 Infanticide Act came from.

I think, ostensibly, it was designed to tackle this problem of so many young unmarried women being pregnant. This would seem to be a moral issue that had to be tackled. Didn't really enter into the heads of the lawmakers to ask why were so many women pregnant outside a wedlock. couldn't be the fault of the men who were raping them.

There's some degeneracy going on in the female population that must be tackled here, and so they passed this absolutely brutal law that treated women who had tragically, you know, found themselves in a situation to be treated as murderers. In situations whereby sometimes it would have been impossible for them to have murdered their child.

Especially in the case of Anne Greene, who miscarried so early on that the midwife, who acted as a witness in the trial, said, the foetus is so unformed, we can't really even say what, you know, I wouldn't even want to say that this is a baby, it's just, in her words, a lump of flesh. Nonetheless, this woman was found guilty of murdering her barely formed foetus and executed.

It's just absolutely mind boggling, and it's these sorts of injustices as I'm reading and writing about them that, yes they don't exist today, but I'm sure that many of us reading these stories can still feel echoes in the modern age. I was talking to a friend of mine. About this chapter and she told me that when she was giving birth on the hospital ward There was a 13 year old girl who had been raped and she was giving birth to her child and the child was whisked away in shame.

The girl had already been sent away to give birth So this is in the memory of you know, people alive today is that these shameful pregnancies that must be hidden. Her pregnancy was hidden and then the child was taken away to be adopted. So it's almost as though this is something so shameful as to be kept secret.

So yeah it's something that survives in the memories of our mothers and our grandmothers. It's nowhere near as extreme as it was in the early modern period, but these attitudes they persist, you know, they don't entirely fade away.

[00:32:58] Jack Wrighton: I think, absolutely, I think that word echo really chimes with, yeah, my experience of, you know, reading passages like that, of oh, you know, you're still so shocked because of how outwardly cruel it is, you know, to be, I mean, punishing these people on multiple levels, you know, as you said, they're already ostracized from society for being unwed mothers and then you're saying, you know, you've gone through this traumatic experience of a, you know, a stillbirth or a miscarriage, and now we're, you know, we're accusing you of murder. But yes, you know, I didn't read it thinking, oh, thank goodness, you know, everything's okay today. Because, you know, there is something, even if you can't pinpoint it, like an attitude or something in the way sort of society operates that still feels, you know, in somehow keyed into that mentality.

[00:33:47] Blessin Adams: Yes. Yes, and something that didn't. Didn't really enter into my head because I was unaware of it at the time as I was writing this book, but I saw a review Someone who had read my book and they made a comment that in some states of America Women who suffer miscarriages are being prosecuted and I just thought to myself What?

Is this true? It's something that I was unaware of. I'm afraid I'm not particularly up to date on America legislation in America what the Americans are up to. But, you know, if this person is accurate, then I thought to myself, well, you know, there we go. He's a modern society that I feel like is very similar to our own.

We have a lot of shared values, but there's something obviously going on there that. I find very difficult to understand. But as you say, it's still happening today, you know?

[00:34:36] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely, and it, you know, it's an interesting thing that we're aware of. I think more is coming out of, you know, about kind of things like you know, bodily autonomy or reproductive rights and things like that. And so hearing a story like that, the fact that we. can even, you know, whether it's true or not think, well, you know, I can imagine that would be the case in some US states, shows that we're not as far from that time as we think we are, but it still feels very real.

[00:35:05] Blessin Adams: Yes, but thankfully, we are not executing women. So, there has been, there is some difference, but you're right. It's like you say, like we talked about those echoes, it's but yeah, and I think as well, like I said before, I've talked, you know, I talked about it earlier, it's that drawing these parallels, even if they are quite distant.

It really feels like the research is still relevant. I sometimes have people ask me, what's the need to have a book now about all these crimes that have happened so long ago? And I thought, well, for one, just because I find it absolutely fascinating and it's something that I want to write about, but as well, like we say, there are these distant echoes.

There are these distant parallels, and I think it's important to make them, and to reflect how far we've come, but in many respects to reflect how far we haven't come.

[00:35:53] Jack Wrighton: Exactly, and I think, you know, reading about another society's, you know, contradictions, I think that's a word you use earlier on, you know, that at one hand they'll do this, and then the other hand, and you're thinking, that doesn't make sense. I think it does open up your mind to them thinking, well, we're still human.

So where are those contradictions in our society today? You know, I think it does help sort of expand the mind to, you know, how well, cause you can't help but feel, how will we look to people in the future? You know, what will we be doing that to them will seem utterly bizarre or shocking even.

[00:36:26] Blessin Adams: I know I know exactly what you mean. It's that time machine again thing, isn't it? It's if we were to hop in a time machine to go to the past, what would they think of us? And if we were to go into the future? I think if we go forwards or backwards, they're going to find us quite disgusting.

[00:36:41] Jack Wrighton: Yes, yeah, we're fine from either side. be acceptance. We'll just be like, oh goodness, you know, we'll stick to our own time then, you know, that's it. Yeah, this is where we belong, obviously. And in terms of these days, as a reader, do you find with your work or with writing, do you have time for reading? And if so, what books have you enjoyed or do you get not much time for reading these.

[00:37:05] Blessin Adams: I read for pleasure outside of work an extraordinary amount of fiction. It's but it's also, I say I read a lot of fiction, but I almost exclusively read romance fiction. So, it's a bit of a joke with my husband that the speed that I read these things, I could put away a book a day quite easily.

[00:37:27] Jack Wrighton: Amazing.

[00:37:30] Blessin Adams: It's just something I really enjoy, and it's such a departure from the sorts of reading that I do for work. So I very much consider the research and the writing that I do to be contained within my working hours. I used to be a huge fan of true crime, and I used to consume a lot of true crime media.

But since I started writing my book, I don't really feel that I want to spend my free time reading true crime, watching true crime documentaries, or listening to true crime podcasts. So that's tapered off. As I've started writing about murder and violent death, my interest in true crime has tapered off as something that I would read in my own time.

Obviously, I read it as part of my working day. So yes, in my own time, I love to read very happy Non confronting, easy, predictable, wonderful romance, guaranteed happy ending. These are books where wonderful things happen to women. Nobody's getting murdered, nobody's getting raped. It's very much my escapism and it brings me a lot of pleasure.

[00:38:41] Jack Wrighton: Are there any particular sort of authors of the genre or any particular titles that have stood out for you that you've just really enjoyed, that you've really loved?

[00:38:49] Blessin Adams: Well, I like the historical romances. I know Bridgerton has been absolutely massive at the moment, and I think Julia Quinn's books are flying off the shelves. I think she's wonderful. I really like, I mean, obviously Georgette Heyer, but again, she's the queen of historical romance. Mary Bailão, and there's a lady called Mimi Matthews who writes Victorian romances that I super enjoy it and you get the feeling as well, because something, I mean, being a historian myself, I really appreciate it when you have authors you can tell have done their historical research. And obviously they're writing fiction, so you don't expect it to be massively accurate. But every now and again you're reading one and you think, oh, This is great!

She's really dug into like the historical background of this particular period and she's really, you know, going for the accuracy. And I think authors like Georgette Heyer and Mimi Matthews, they strive for more historical accuracy than someone like Julia Quinn, who has a historical setting, but I think her characters are quite modern. Yeah, I think those would be my recommendations. I love Mary Bailão, I love Mimi Matthews.

[00:39:49] Jack Wrighton: Yes.

[00:39:50] Blessin Adams: They're kind of like the Regency Romance, Pride and Prejudice style periods. I love it.

[00:39:55] Jack Wrighton: And it adds to that escapism I feel as well, when it's like a period of history as well. Because it's kind of, you know, again, it's familiar, but there's enough kind of removed that you're like, oh, I can imagine wearing, you know. Having tea in some lovely rooms somewhere. I don't know, but you know, I think that's the things to think of.

[00:40:13] Blessin Adams: Do you know the funny thing is when I'm reading these, I always think to myself how utterly suffocating it must have been like all these manners and these rules and the dress codes and you know how deeply do you curtsy depending on who you're talking to I think to thank god I don't live then or thank god I'm not of that class living then because that sounds exhausting so it's fun to read about but I've always got in the back of my head oh come on unwind a little bit.

[00:40:39] Jack Wrighton: Yes. Actually, I think being in that class of people, then I imagine probably a lot of boredom because, you know, you, if you didn't have a job, you know, you were just kind of of independent means. I just imagine there was probably a lot of sitting around because that you were constricted in terms of what you could do. I just imagine, yeah, there would be a lot of, yeah, thinking, a lot of...

[00:41:00] Blessin Adams: Especially if you're a woman. I mean, at least the blokes could go out and, you know, join a club or go gambling or something, I guess. But yeah I mean, I'm judging this all on my extensive research reading historical romance here. I am not a historian of the Regency era. So forgive me if I get things horrifically wrong but from my research reading romance I believe that These women just sat around in drawing rooms all day waiting to get married at the ancient age of 17.

It seems as soon as you hit your twenties, you're an old hag and you can't get married. So it's, but yeah, no, I know what you mean. It's not something that I would if we had our time machine, I probably wouldn't be going to a Regency ball, a bit too uptight for me.

[00:41:44] Jack Wrighton: Yeah. You'd be out in the street somewhere I feel like seeing how the everyday, yeah, the everyday people live. Okay, so some good recommendations there. I like those. So going, we're moving from the Regency period now and from romances back to the sort of grittier side of the early modern period. So was it with that particular story of the miscarriage? And it was with that story that your book began with?

[00:42:11] Blessin Adams: Yes. So, I started with Elizabeth and I sat on Elizabeth's story for probably about five years. It was something I knew I always wanted to write about, but I wanted to give it the time. And so, I started with Elizabeth's story and I delved into it and and then from there I just really started reading very broadly about the theme of murder, criminal investigation, and the legal system in the early modern period.

I just thought it was so interesting because the whole business with the law concerning miscarriages was to me fascinating. Having been in law enforcement and okay, on the blunt end of the law I found that side of things incredibly fascinating. How did the early moderns investigate crimes?

How did they prosecute suspected criminals? What happens next? You know, when the court case is over and they're waiting to be executed, what's that these are the sorts of things that I find absolutely fascinating. So, it was as I was sort of like digging into these themes broadly that then I started coming across other cases.

I started hitting the archives and I started digging deeper into other... stories. Some of the cases I write about are perhaps a little bit more famous. So the business of syndicum involves a chap who tried to assassinate Oliver Cromwell. So that's something people may perhaps have come across if they've read a biography of Cromwell or something, that would have been a name that they would have come across. But then there's other people, such as the case of Francis Marshall, who's just a farmer. Who was found dead in a pool of water. And there was all this legal drama that just explodes on the discovery of his body. And this is a story that I'm wondering if anybody's heard of it. I found it in the Star Chamber records.

Just three pages of complaints and answers. Involving these people that were embroiled in this case. But from these manuscripts I was able to pull out an awful lot of detail. On a story that I thought was quite extraordinary. It involved a family mutilating the corpse of their loved, recently deceased father in order to avoid having to pay what was called felony forfeiture. In order to save their inheritance, they had to brutalize the corpse of their father. And that touched me, I found it very emotional because when I started writing my book, I had just lost my father, he died suddenly and it was something that was always in the back of my mind. As I was writing this book, when I was reading about people who had suffered loss, who had suffered the death of a loved one, I felt an enormous sympathy for those historical people, because I had recently been through the same thing. So when I was reading about the case of Francis Marshall, Although you might say that his family acted in an incredibly violent and unethical way, I couldn't help but sympathize with their situation. I felt like they were compelled by unjust laws to do this dreadful thing to the body of their loved one. So it's these sorts of stories that I'm researching them and investigating them, sometimes they speak to me on a personal level, and I know that other people who have read my book and have gotten in touch with me, there are stories that have not touched me at all on a personal level, but they've gotten back to me to say, this is something that's really familiar to me and I just thought, you goodness, you know, it's it's extraordinary, and again, it just goes back to the idea that some things never change, you know. People suffered from trauma and loss and grief in the early modern period, and although they would have done so through a cultural lens that's very different from our own, there are things that I think are just on a basic human level that we can have in common with our ancestors from hundreds of years ago.

And that's what I like to dig into and what I like to write about when I read these cases. I don't just want to write about the legal side of things. I to be descriptive and talk about crime scenes and... brutal murders. I like to dig into the human side of the story as well. How are people thinking? How are people feeling?

What was it like? What was it like to find a dead body in these circumstances? You know?

[00:46:11] Jack Wrighton: That was a chapter, the Francis Marshall one, that really stood out for me because of the, you know, just imagining what the situation would be like. That not only have you lost this you know, loved member of your family and you set the scene really well in terms of the research and how, you know, we know where they lived and, you know, what their lives were like and that they were relatively sort of wealthy or, you know, comfortably off and the idea that you could then lose a member of your family and not really know the circumstances of it, but that... Because it could be deemed as suicide, that you could lose everything in a world where losing everything, as you said earlier, could lead to starvation. You know, it's losing everything in a way that I feel is hard to fathom now because we do have some safety nets in our society.

But then I feel you know, what would have that have meant? It would have been horrifying.

[00:47:07] Blessin Adams: Yes. I mean, it would have been everything. It would have been everything to this family. And touching as well, sort of like on, on things that we find difficult to understand from a modern perspective, looking back into the early modern period, is talking about the attitudes to suicide in that period. So, suicide was deemed to be one of the worst crimes imaginable.

It was equal to murder. I mean, it was a species of murder. It was prosecuted as self murder. Philo de se, to commit a felony against yourself, and people who had committed suicide, their bodies were desecrated, they were denied Christian burial, and their families were punished by having their inheritances forfeited to the crown.

So it was a big deal. It was a huge deal to have a suspected suicide in your family. was utterly ruinous. Just from a social standpoint, if you were in the community and a family member committed suicide, you could find it very difficult to get by, never mind if you have all of your possessions taken from you.

I found it quite sad when I was going through So it was the job of the coroner to catalogue people's worldly possessions and with the eye that he might have to seize those possessions in cases of suicide. So he was prepared. He would examine the body and he would cast an eye over their worldly goods and reading through the coroner's records when they're cataloguing the goods of people who have committed suicide usually poor people, or the majority of people who have committed suicide in this period, men, and it was things like They had a coat, they had some salt cellars, they had a box but it was empty, and these are the things that are being taken, and you just think to yourself, why? There's no value to these items. Yes, there is money to be made if you have a wealthy person who commits suicide. The crown can benefit financially from their death. But in the grand scheme of things, it was just to punish the families. In my opinion, it was solely to punish the families of people who committed suicide.

To act as a deterrent, perhaps. If you knew that your family were going to be destitute because you killed yourself, it might be something to hold your hand at the last moment. But, you know, people who are on the cusp of committing suicide, they're not always in the mind space to consider the financial ramifications that comes afterwards.

It's... absolutely heartbreaking, and it's so hard to understand. But again just going back and saying, you know, oh, I was talking to a family member about this. And again, in living memory, people have been denied burials. I think it was 1961 that suicide was decriminalized. I believe it was 2015 that the Church of England permitted full Christian burials of people who'd committed suicide, I might be wrong on that, I'll have to go and check. But It was recent. It was very recent. So again the things have changed. We don't have felony forfeiture anymore. We don't desecrate the corpses of suicides. We don't hammer stakes through their chests and bury them at crossroads, but there are still these attitudes that have persisted long into the modern age and within living memory of certainly people that I've spoken to, and can you imagine that? A loved one has tragically committed suicide in a manner that is incredibly violent and disturbing. You have to deal with that anyway, but then you have to go through the process of being fined.

You're not in the headspace to deal with this at all. That's something I feel comes across when I'm writing about the case of Francis Marshall. His family is standing around his corpse and they know that the coroner is going to be there within hours. And there's people standing around whispering, this looks like a suicide to me.

They've got to act in the moment of discovery. They have to make a decision, and I just think to myself, God, what would that have been like? It must have been so hard.

[00:50:53] Jack Wrighton: I think one of the touching things I found about that story, there's so much in this book that, if you're listening, don't worry, I'm not giving too much away, that there's so many things to discover, but is how at least a good portion of the community seemed to rally around the family slightly, that there was a kind of a consensus of, we're kind of sticking to the narrative here in order to protect this kind of, it seemed like they were, you know, good members of their community and people wanted to protect

[00:51:21] Blessin Adams: Yes, social attitudes to suicide in the early modern period are incredibly complex and incredibly interesting. I write a great deal about the disgust that people had for suicide and the hatred they had towards those who had killed themselves. And it's something that comes up in several chapters, and I discuss in quite a bit of detail.

So it might be a bit, it might feel like a contradiction. Then when we get to this chapter, and there's an outpouring of sympathy in the community, and sympathy towards the family and support, and people really putting themselves out there, putting their neck on the line, willing to perjure themselves in a coroner's inquest to support their neighbours and their family members, because although there was an enormous amount of disgust towards the act of suicide, there was also a great deal of resentment towards felony forfeiture.

It was considered good and proper to desecrate the corpses of suicides, but it was considered unjust to then go and punish their family members, because the family members were truly innocent. They had not done anything. So even if you were to argue that suicide was a crime, you couldn't argue that the family members were accomplices, or that they were somehow culpable, or that they were also criminals.

So this is something that really riled. Local communities that they and the records of Court of Star Chamber are absolutely bursting with accounts of people resisting felony forfeiture, of people trying to avoid it. I believe one of the cases I briefly allude to was some doctors or some surgeons who had quite hilariously in a strange dark humor way, argued that a chap who'd cut his own throat had died of natural causes. They were doing all in their power to try and help the family here, but there's only so far you can argue that a knife wound to the throat is natural causes. But people would go to extremes to try and avoid felony forfeiture and they would support each other.

So yes, it's one of those strange contradictions in attitudes towards suicide in the early modern period in that it was universally reviled, but at the same time, there were corners in people's hearts for sympathy as well. So...

[00:53:26] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely, and I won't, again, because I don't want to give too much away, but looking at that kind of the, how attitudes were so varied within the one period is really beautifully reflected, and again, very touchingly in the final story, in the final case that we look at in the book, that's a, you know, a one that really stood out for me as well, how, you know, circumstances, who it was, why, could really change people's attitudes towards suicide.

[00:53:55] Blessin Adams: Yes so the case you're talking about is the case of John Temple, who was a young man thrown, I think, far too early into the cutthroat world of the early modern politics, and he found himself on the world stage as the minister of war, and he messed up spectacularly within his first week in office and was quite humiliated and dishonored in front of not only his peers, but in front of the country. So, he very sadly decided to take his own life, and what I'm really digging into, what I'm really delving into this chapter, In many ways is is the concept of honorable suicide in this period. Because as I said before, suicide was so universally reviled, and you imagine that you have a popular mindset that says that suicide is one of the worst crimes you can commit.

But then you also have a people that would admire historical figures. Like Cato, the Roman politician who killed himself rather than submit to Caesar, this was a figure that the humanists lauded. Or someone like Lucretia, again another classical figure, a woman who killed herself after being raped to preserve her honor.

To us it sounds horrific, but to, to the ancients this was something to be admired. Or where do you draw the line with somebody like the Marian martyrs? Somebody who willingly goes to be executed in the name of their faith. Is this suicide? So these are the, or is this something else? So these are like the tricky moral ethical issues that people were trying to figure out in this day, in this age and I think the case of John Marshall, he killed himself because he hoped to preserve his honor. He hoped to put right something that he thought he'd done wrong, and I just thought it was an interesting way to sort of like return to the subject of suicide and just acknowledge the fact that it was incredibly complex and people in the end of modern period. Had very paradoxical views, I guess you could say, about this particular subject. Something really fascinating, really interesting to dig into. But again, at the heart of it as well, you have this poor young man who is trying to orchestrate for himself a suicide that, in the aftermath, he hopes that he will be remembered with honour rather than disgust.

How successful he was, it's down to the individual, I think. Some reporters were very sympathetic towards him, others thought it was disgusting. So, it was just, very sad story. But again, I mean, I'm really fascinated by suicide, which is why I think I touched upon it in several of my chapters, because it was so universally reviled and it was something that the early ones were absolutely obsessed with. They wrote about it all the time. A lot of the true crime literature, a lot of this, the street literature, the pamphlets covers the subject of suicide. Excessively. And I just thought to myself, why? Why were they so interested in suicide?

Why was it such a big deal? So it's something that I really wanted to do, dig into with several of the cases in my book.

[00:56:57] Jack Wrighton: And you absolutely do, and it's one of the many threads in the book that make it so interesting, and those contradictions, as you say, which absolutely pepper this book in terms of people's attitudes that make it truly a really engaging read, and I thoroughly enjoyed it, and unfortunately, I've realized looking at the time that we're coming to the end now of our conversation and I was wondering, I always like to end on a little reading. Would you mind doing a reading from your book?

[00:57:23] Blessin Adams: Yes, of course. Newgate Prison stood on the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street, just a short walk from the Old Bailey Courthouse. It was a truly frightening place, its name a byword for unimaginable suffering. Every class of criminal, from debtors to murderers, were crammed together inside its dark, imposing walls.

There was no sanitation, no clean running water, no ventilation, and almost no light. Inmates awaiting trial or serving out their sentences languished in vermin infested dungeons, and jail fever, typhus, spread like wildfire through the prison's malnourished population. One visitor to Newgate described it as a terrible, stinking, dark and dismal place, situated underground, into which no daylight can come.

Everyday acts of violence stripped the men and women of Newgate, of their humanity. They were oppressed not only by their jailers, but by each other as well. Relief could only be purchased through the payment of exorbitant bribes. However, these small creature comforts could not inure the inmates to the brutality of their surroundings.

In 1670, a newly admitted prisoner to Newgate described walking into the yard to see an executioner fresh from the scaffold. preparing to boil quartered human remains in an enormous kettle. Before he plunged the severed heads into the water, the executioner threw them to a crowd of felons, who laughed and jeered as they tossed the heads like balls, pulled their hair and beat them with their fists.

[00:59:06] Jack Wrighton: I think if we did have that time machine, I don't think I would be going to Newgate prison as one of my tourist hotspots.

[00:59:13] Blessin Adams: Absolutely not. Well, you would hope so. Just don't commit a crime when you're when you're there.

[00:59:20] Jack Wrighton: No, absolutely not. Absolutely not. That's such an evocative reading there of what a place like Newgate must have been like. Blessin, thank you so much for joining us on Mostly Books Meets. It's been an absolute pleasure. Great and Horrible News is available now in Mostly Books, physically in our shop, online as well, but it's also available from your local independent wherever you are. Blessin Adams, thank you so much for joining us on Mostly Books Meets.

[00:59:43] Blessin Adams: Thank you.

[00:59:45] Jack Wrighton: Mostly Books Meets is presented and produced by the bookselling team at Mostly Books, an award winning bookshop located in Abingdon, Oxfordshire.

All of the titles mentioned in this episode are available through our shop or your preferred local independent. If you enjoyed this episode, be sure to check out our previous guests, which include some of the most exciting voices in the world of books. Thanks for listening and happy reading.