- New tariffs announced by the U.S. government: 50% on semiconductors, 25% on steel and aluminum, 100% on EVs, and 50% on solar panels from China.

- The Raspberry Pi Foundation announced an M.2 hat for the Raspberry Pi.

- Time modulation in capacitors and the new dielectric structure using barium titanate.

- The concept of heterojunctions and homojunctions in semiconductors.

- Efficiency improvements in capacitors and their potential applications.

- The practical implications and future prospects of new capacitor technology.

- Discussion on AI-generated content and the dead internet theory.

- New tariffs on semiconductors and other goods from China and their potential impact.

- The Raspberry Pi Foundation's new M.2 hat and its benefits for storage solutions.

- Parker's personal project updates, including the digital control upgrade for a 1965 Checker Marathon engine.

- The use of flatbed scanners for reverse engineering enclosures and components.

- The potential future of neural interfaces and their ethical implications.

- High energy density in artificial heterostructures through relaxation time modulation

- China's Share of Global Chip Sales

- Raspberry Pi Foundation M.2 hat announcement

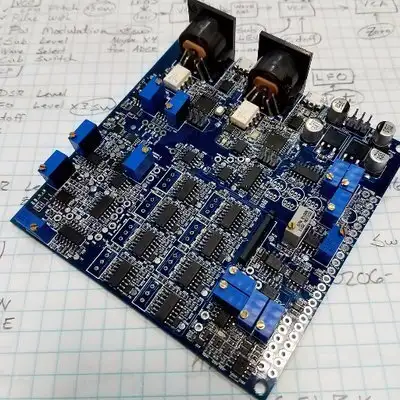

- MegaSquirt 3 EFI Controller

- Dead Internet Theory

- Flatbed scanner reverse engineering tutorial

- Would you be willing to integrate a smartphone into your body if it was 100% safe and reversible?

- Have you used a flatbed scanner for any unique engineering applications?

- What are your thoughts on the new semiconductor tariffs? How do you think it will impact the industry?

Creators and Guests

What is Circuit Break - A MacroFab Podcast?

Dive into the electrifying world of electrical engineering with Circuit Break, a MacroFab podcast hosted by Parker Dillmann and Stephen Kraig. This dynamic duo, armed with practical experience and a palpable passion for tech, explores the latest innovations, industry news, and practical challenges in the field. From DIY project hurdles to deep dives with industry experts, Parker and Stephen's real-world insights provide an engaging learning experience that bridges theory and practice for engineers at any stage of their career.

Whether you're a student eager to grasp what the job market seeks, or an engineer keen to stay ahead in the fast-paced tech world, Circuit Break is your go-to. The hosts, alongside a vibrant community of engineers, makers, and leaders, dissect product evolutions, demystify the journey of tech from lab to market, and reverse engineer the processes behind groundbreaking advancements. Their candid discussions not only enlighten but also inspire listeners to explore the limitless possibilities within electrical engineering.

Presented by MacroFab, a leader in electronics manufacturing services, Circuit Break connects listeners directly to the forefront of PCB design, assembly, and innovation. MacroFab's platform exemplifies the seamless integration of design and manufacturing, catering to a broad audience from hobbyists to professionals.

About the hosts: Parker, an expert in Embedded System Design and DSP, and Stephen, an aficionado of audio electronics and brewing tech, bring a wealth of knowledge and a unique perspective to the show. Their backgrounds in engineering and hands-on projects make each episode a blend of expertise, enthusiasm, and practical advice.

Join the conversation and community at our online engineering forum, where we delve deeper into each episode's content, gather your feedback, and explore the topics you're curious about. Subscribe to Circuit Break on your favorite podcast platform and become part of our journey through the fascinating world of electrical engineering.

Welcome to circuit break from MacroFab, a weekly podcast about all things engineering, DIY projects, manufacturing, industry news, and now time modulation. We're your hosts, electrical engineers, Parker Dillmann.

Stephen Kraig:And Stephen Kraig.

Parker Dillmann:This is episode 431. So, yeah, time modulation. This one been a great topic for episode 420, but we are going to we had James Lewis on for that one, didn't we?

Stephen Kraig:Did was that 420? Yeah. That that was when we were talking about was that when we were talking about reliability

Parker Dillmann:no it was his

Stephen Kraig:no is apple 2

Parker Dillmann:is apple 2 mega yeah the mega 2 I'm making sure it's that was that episode Yeah, episode 4 20, and I said blaze it

Stephen Kraig:yeah, that's right.

Parker Dillmann:And that made it and that made it into the episode. Alright. So, yes, time modulation in regards with capacitors. We're We're not actually gonna be talking a lot about capacitors except with this article. It's a a research paper about a different structure for the dielectric.

Parker Dillmann:I wasn't able to get the paper because they have you have to pay for it. Yeah. Even though

Stephen Kraig:it's behind a

Parker Dillmann:paper and my tax dollars actually paid for this research but this is a society that we live in so so this new dielectric is a heterostructure of berymium night Knight. What is that? 9 berrymium titanate. Tight. Well, that's a I wonder what that is.

Stephen Kraig:That's a hell of a name.

Parker Dillmann:But it's sandwiched between 2 other structures. I think the paper probably covers more of what it is, this material, but it's a they have a 2 d material, and then they this 3 d barium titanate. Titanate. Man, I am never gonna say that correct. And that's a 3 d structure probably because it's a crystal whatever its crystal structure is, it's 3 d.

Stephen Kraig:Sure.

Parker Dillmann:Versus a 2 d crystal structure, and then there's another 2 d on top. So it makes like an ice cream sandwich of semiconductor material, but it's the thing is they can make it really thin as well. We're talking atoms thin and but I had to go look up what a heterostructure was because I was like, it's been a long time since I've done semiconductor physics, and I've actually never done that outside of school. So a heterojunction is basically the interface between 2 layers of dissimilar semiconductors that have unequal band gaps. And so solar cells are really common heterojunction material.

Stephen Kraig:I I like this. Okay. So you you this is originally defined as a heterostructure, and I love these kinds of definitions because it, the definition of a heterostructure, it says it's a device that contains multiple heterojunctions. And it's cool. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Go look at that up. Let me go look what that means.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That that was me about 3 hours ago.

Stephen Kraig:That's great.

Parker Dillmann:And so I'm like, okay. What about the opposite? What's a the ho a homo junction? And it's different materials, but they have equal band gaps. And usually, that's achieved by different doping.

Parker Dillmann:So diode p n junction, that's a that's a a homojunction. Mhmm. So they had so the materials have the same band gaps, but they're achieved, you know, with different doping. So it's a different material. So the big claim of this whole article or not this article, this, this research paper is they were able to basically increase the density of a capacitor over a commercial capacitor by 19 times and then also the efficiency.

Parker Dillmann:That's actually was the more important thing to me at least was the efficiency gains. So, like, I wish I could get the paper so I can actually read what they actually mean by they say 90% efficiency, which I don't know what efficiency. Yeah. You you need loss, energy stored. I don't know.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. There needs to be a definition of that. Also, I we've we've talked about these kinds of things multiple times on the podcast where there's this really cool breakthrough. And I'm and and in no way am I downplaying what the breakthrough is. But in so many ways, the breakthrough is what's focused on, but the practical aspect of what we get from this breakthrough is still potentially years away or maybe not even.

Stephen Kraig:Like, we I think we talked about, the the room temperature, superconductors, and and and I would not be surprised if everything in this paper is absolutely correct, but their capacitors that have a max voltage of 1 volt or something like that. Right? Because there's not a lot of information behind all that. Although, the claim here is that they have 19 times the energy density of commercial capacitors, and I'm wondering if the use of the word commercial is a one to one comparison. Reg regardless, I mean, this would be really fit.

Stephen Kraig:Everyone's always looking for these huge leaps in technology. Right? And numbers like 19 times or we've reduced leakage by a 1,000,000,000 or something like that. It's great, but what does that actually mean?

Parker Dillmann:Yes. So if if efficiency, I think, from what I was able I was reading in between the lines of what I could find about this is it's in basically leakage current. Sure. Because they're they're able to basically more accurately control the time modulation or the dielectric modulation of in between the layers, basically, with this 3 d structure. And And so they can get everything tighter and closer, and, basically, it basically just improves the overall efficiency of the capacitor.

Parker Dillmann:The closer you can get your plates, the more fit the better your capacitor actually is gonna be. Mhmm. But then you typically have more leakage currents. Correct. Because it's easier for the electrons to just shoot across the dielectric, but apparently this three d structure prevents that somehow.

Parker Dillmann:I I wish I knew more, but what's interesting is they actually do claim a 191 joules per cubic centimeter. You can actually read that in the abstract. Mhmm. So during I did some quick math, which that turns out to be, like, 53 watt hours per liter. I love metric conversions like this because thinking of wattage per volume volume of liquid is super funny.

Parker Dillmann:We're, like, we would think of it as we would think about it as density. Oh, I guess that's why it works. It's like a milliliter is equal to a centimeter cubic of water. So that's somewhat so it makes the conversion that way easy, but it's it feels weird to think of it as to us, a liter is liquid, but in other, maybe more civilized countries, that is is just volume.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And this is energy per volume.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Energy per volume. I just think per liter. I'm I'm just imagining what's that movie? Is it Supercop?

Parker Dillmann:What he wants a a cheeseburger with a liter cola?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, no. Super Troopers. Yeah. Super Troopers. That's it.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. This is I I'm flashing back to that scene.

Stephen Kraig:It's for a cup.

Parker Dillmann:Does he look like he's spitting my burger? Yeah. It does.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I guess I guess it it does make sense big with us with us always trying to miniaturize everything, it makes sense to to focus in on how much energy we could put in the smallest amount of area and hold it. Right? And be efficient. Right?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:So 53 watt hours per liter, lithium batteries are 500 to 600 watt hours per liter. So we're actually it's still 10 x off, but it's within stabbing distance now over lithium battery in terms of energy density. And you're talking about, I'm assuming, way less, you know, environmental problems with strip mining lithium and and all those rare earth metals, but, of course, I don't know what it takes to make barium titanite titanate. Yeah. I was just about to say,

Stephen Kraig:this is this might be another one of those, like I was saying earlier with, oh, cool. We've we've taken this massive leap and all of all the things are fantastic, but it requires this ridiculous crystal that is very difficult to grow and and super not ready for any kind of game day in terms of quantity. So I don't know about barium titanite if that's something that could be done on scale.

Parker Dillmann:But I don't know.

Stephen Kraig:It it does. I don't know. The way that this is structured kinda makes it seem like they're trying to make the best possible capacitor given the material they have. And what I mean by that is if you could artificially grow a crystal in a perfect way such that the layer is exactly the dimensions that you want every layer, could you end up making literally the best capacitor given that material? There's nothing more you could do because you have optimized every bit about the crystal.

Stephen Kraig:And it kinda sounds like they're approaching it in that kind of way.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. There there's also some talk about the notes section where these researchers weren't even trying to improve capacitors. This was kinda like a spin off of other research, and they're like, oh, this is an interesting effect that's happening. Let's go explore that real quick.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, that's pretty

Parker Dillmann:And then they and they lead to this big break well, potentially big breakthrough. What's also interesting though is when you Google the this article, you find a couple news articles out there, and It's amazing what is Written about it because it's all pointing to everyone's oh, this is gonna make EV batteries better or this is gonna make cell phone bad smartphones better. It's totally like trying to play off like battery tech.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Whereas, technically, this tech has nothing to do with making batteries better.

Stephen Kraig:And you just showed that they're an order of magnitude worse than what already exists.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Their order of magnitude was now, I this there is. What's interesting is that these articles are like, oh, it's gonna make batteries better blah blah, but they don't explain why or how Yeah. That would happen. It's just I honestly think these articles are just written by AI.

Parker Dillmann:They could be. And they go write an article about this at they probably just took the abstract through that chat gpt and say, connect us to smartphone batteries, and write a 4 paragraph article about it. I bet you that's what happened.

Stephen Kraig:I okay. That that brings up a thought that's a little bit scary. Could you go to whatever AI, and have it write a scientific paper about some material and have it just make a whole bunch of claims about stuff and then just post that on the Internet and see if people run with it. The answer is yes, of course. Right?

Stephen Kraig:But I guess my question my real question is how hard would that be? And I I don't condone doing that's heavily deceiving people, but it wouldn't surprise me if you put that up there. If there would be articles within a few hours of other AIs saying, oh, your the world's gonna be amazing because of this scientific paper that came out.

Parker Dillmann:That's the dead Internet theory.

Stephen Kraig:I don't believe I've heard that. What is that?

Parker Dillmann:So dead Internet theory is the conspiracy I'm doing air quotes here because I actually think this is proven now at this point. But it it it's a it it asserts that the Internet consists mainly of bot activity and automatically generate content to manipulate, like, algorithm creations and stuff like that. So, like

Stephen Kraig:Oh, sure.

Parker Dillmann:Basically over the idea is, like, over 50% of the content that you look at on the Internet is most likely AI built and driven, including comments on videos and threads. Maybe not forms, but in on Reddit, social media, that kind of stuff. That would not I, yeah. I I agree with this, with that Internet theory because it's very easy. Especially nowadays.

Parker Dillmann:It's they the the conspiracy says it would it was starting around, like, 2016, 2017 was, like, the tipping point, and looking at chat gpt what you can make it do. It's yeah. I don't know if we're at, like, quite, like, 90% of the content online, but probably pretty close.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I remember I a few years ago, Twitter, I think it was. Yeah. I believe it was Twitter, went on a ban rampage of just getting rid of bots. And, I mean, there were huge portions of people's follower bases that were just getting axed.

Stephen Kraig:And, I mean, I saw numbers up in the 100 of 1,000 in terms of individual content creators losing 100 of 1000 of followers, they were just bots. And so it was bots liking other bots, and, yeah, it was just absolutely ridiculous. And this was years ago. So, I mean, I can only imagine something like that is considerably worse now. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:But when do we get to the point where AI starts referencing AI, which it probably already is.

Parker Dillmann:It already does.

Stephen Kraig:So but that's exactly my point with the scientific paper. How do we even prove that those papers are created by a human now?

Parker Dillmann:You do that by fact check like, actually checking it, because you have to, like the whole point with a pay a paper like this is you should be able to replicate it in your own lab.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. But people have to actually go and do that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. The there is a theory about AI referencing other AI. What? It's another one of those, like, conspiracy theories. Sorry.

Parker Dillmann:I'm trying to Google this real quick.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I'm thinking you could pick a well, pick pick a a really hot topic. Let's say you were to convince an AI to write something about fusion is here and this one company that you've never heard of had this breakthrough and they're producing 10.6, you know, gigawatts of power or whatever. And, I wonder how fast it would be that articles would just pop up without fact checking that. I mean, instantly.

Parker Dillmann:So I'm googling AI referencing AI conspiracy, and the articles that are popping up under that search term are all AI. Right. Like this article titled chatbots can persuade conspiracy theorists their their view might be wrong up to 20% of the time. Okay. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:So you can so chatbots can so chatbots are more persuasive in changing people's mind on the Internet than normal people talking to normal people.

Stephen Kraig:Wow. Yikes. That's frightening. Yeah. Yikes.

Stephen Kraig:So, I don't know. When do we bow down to our supreme tech overlords?

Parker Dillmann:I don't know yet. Well, we already do. We already have a phone that's we have a computer that's glued to us all the time. It's just not integrated into our body yet.

Stephen Kraig:Yet. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:So I'm gonna finish up this topic Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And then

Parker Dillmann:I wanna I don't wanna I want to branch onto what I just said there, though. Sure. So this tech can make it I don't it won't be able to make your smartphone battery better at all. The use case is there, but it could make your EV battery better, because of regenerative braking. So the problem with basically lifting batteries and regenerative braking is you put a lot of wattage basically back into your battery and charge it, which causes a lot of charge and discharge cycles.

Parker Dillmann:Accelerating braking, accelerating braking. So you have this surge, reversing surge, and the batteries don't really like that, and they heat up. And that's why you have to have active cooling on your batteries, on EVs. If you don't, you have really premature battery life. Look at the Nissan LEAF.

Parker Dillmann:Doesn't have that. Its batteries don't last as long as a Tesla, because Tesla batteries have, like, industry leading battery life because their their recharge and regenerative cycles are really good, and they keep the batteries cool. Anyways, so what you could do is you could have this buffer of capacitors. Now you could do that nowadays, but the problem with capacitors now that it's actually super caps because you might have a super cap style battery to handle the surge of input. The charge back up is the leakage because you it rapidly dissipates, and you might lose 30% of your power just sitting there at the red light.

Parker Dillmann:Right? Mhmm. As the battery just self dissipates. Well, if you have these batteries, now you can have a super cap that has much greater efficiency, and it can retain its charge for a lot longer. And now you can have the super cap taking up that buffer spot of the charge and discharge rapid cycle and save your lithium battery for continuous charge and continuous discharging.

Parker Dillmann:So that could. Thing is the articles that I've talk I'm talking about don't even mention that at all. That's just something I thought of.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I I guess it's starting to blur the line a little bit. Well, this kind of thing blurs the line a little between a capacitor and a battery. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's getting there. I mean, they just increased the density by 10 x. Just 10 x, guys. Just 10 more.

Stephen Kraig:No. That's all.

Parker Dillmann:10 more.

Stephen Kraig:Thanks.

Parker Dillmann:Just please, 10 more. Just 10 more. That's all we need. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I guess one of the big bigger differences is batteries tend to clamp more a voltage. They maintain the voltage, whereas the the thing about a capacitor is that it it tends to have more variation in in voltage as it discharges.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. But you can fix that with a, you know, a buck boost. Like, you can Oh, sure. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, of course, there's there's ways to adjust that. I'm just saying on a more inherent level Scale. The

Parker Dillmann:I mean, you're always gonna have a a discharge voltage rate, unlike a lithium battery, which will have a a sharp drop, a really flat, long voltage line, and then a sharp drop off.

Stephen Kraig:Right. But the but the fundamentals between what a battery is and a capacitor is, they they they are different physically. I'm saying the physics behind them is is is different.

Parker Dillmann:But One's one's chemically, and one is electro well, it's not mechanical. Just let it's just

Stephen Kraig:just stored. Yeah. So but but but in terms of their energy density, that is starting to get blurred a little bit, I guess.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Oh, yeah. Just just 10 more just shove 10 times more electrons in there, and we're good to go.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, the the good the one of the main benefits of a capacitor or maybe not main, but a big benefit of them is that they can withstand a lot more charging discharging, but they a lot of that has to do with their construction and their inherent resistance in there Yep. Which batteries tend to have much higher internal resistances. So, you know, if we could just have a giant capacitor in there, hey, why not? But I don't know. Still sounds like we're a bit off.

Parker Dillmann:A little bit. But, I mean, what's the watt per watt hours per liter of lead acid?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, I don't Yeah. I'd have to look it up.

Parker Dillmann:Lead acid ranges from 60 to 200 watt hours per liter. So it's actually nearing like the cheapy sealed lead acid batteries. Yes. Yeah. Now those also have

Stephen Kraig:a lot

Parker Dillmann:longer discharge rate in terms of voltage. They don't drop off as hard as a capacitor will, so you're gonna need more circuitry to handle that.

Stephen Kraig:Mhmm.

Parker Dillmann:But you're getting close to, you know, replacing low end lead acid batteries with a capacitor, really.

Stephen Kraig:Is lit is lithium ion basically the best we have right now in terms of energy density?

Parker Dillmann:Pretty close. I think there's lithium ion. There's other formulas of lithium ion

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:That are more dense, but, yes, that that family is the most dense.

Stephen Kraig:I'm looking at a chart now that shows an area of lithium that it just says unsafe, as in just don't make this kind of battery even though it it's theoretically possible. Too unstable? Yeah. Something of that sort. And, yeah, let for for these there's multiple charts I'm seeing here that are battery energy density charts.

Stephen Kraig:And on one side, the the low end is lead acid, and on the high end is just lithium ion. There's a bunch of stuff in between, but the that is So That's the spread. In

Parker Dillmann:the 19 eighties, when GM made the EV 1, which ran on lead acid I no. Actually, no. That's wrong. I think it was a Nike ads, actually. But, anyways, your golf cart

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Can run off these capacitors. You could start your car off these capacitors.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. I wonder I wonder how they hold up to temperature cycles though. Can Yeah. Would are these things happy with starting up in Alaska or starting up in the Sahara Desert, you know, with the same the exact same everything.

Parker Dillmann:Well, you could go from you can start out in Death Valley in the morning Yeah. And then drive to 13,000 something feet in Colorado in one day. Will that battery still work?

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Yeah. You're changing a lot of variables with that,

Parker Dillmann:Which is the good thing about a sealed lead acid battery is they're very mature and reliable technology.

Stephen Kraig:That's that's the word. If it is negative 20 outside, you can turn your key in. It will still turn that starter over.

Parker Dillmann:So I was talking about earlier about smartphones being glued to us. Would you, if it was a 100% safe and let's even say reversible, would you put a smartphone in your head? No. I don't know how you would interface with it, but think of that. Think of,

Stephen Kraig:like, Futurama where they stick it in their eye. Right? The wasn't it the iPhone? Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:The stuck in your eyeball. Because there was that it it was the Neuralink. There's a person that they actually hooked a Neuralink up to a person, and The person who who has his he's he likes it right now. Of course, I think that person's terminal. I mean we all are but he's terminal on a known scale, I guess.

Parker Dillmann:Mhmm. The he's like controlling computers basically directly with his the neurons in his brain, which is kind of exciting to see. And what's really interesting about that technology, I think I said this back when it first came out, but the they had a release video. This is, like, their first public demo, I think, of Neuralink, and I think they had it on pigs. The they had some, like, electrodes in the back of the pit in the pig.

Parker Dillmann:Right. And they had a the pig was just, like, walking around, and then they had a 3 d model of the pig in the same space that was just reading the neurons. Right? And it was able to basically simulate the pig in in the virtual world. So the idea would be you could let's say a prosthetic.

Parker Dillmann:So let's say you get your arm cut off. Right now, it's our prosthetics are better material wise, but they still don't really have a good way to you to control them. It's not like Star Wars where getting your arm cut off in Star Wars is just an inconvenience. You just get a robot arm, and it's fine. No one seems to really complain too much about it.

Parker Dillmann:And so a Neuralink kinda interface would facilitate that kinda technology. But let's just say you have all your digits and all your hands and legs and everything. Would you connect yourself to a cell phone via BrainLink?

Stephen Kraig:No. The answer's that that's not even in question.

Parker Dillmann:No. No. You would never do it?

Stephen Kraig:No. I think we're still a generation, maybe a generation and a half off of people growing up with technology so integrated into your life that you're willing to make those kinds of changes. I think you and I are gonna be of the generation where we'll be the old people drinking a beer out on our porch and just enjoying the sunset where everyone else is, like, jacking into the matrix. Right? Like, we may be the last of that.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, well, I might wanna jack into the matrix. That sounds cool.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, don't get me wrong. It sounds cool. I don't I do not trust people enough to do that. And I'm not saying to mess with my mind. I just think that that is rife with potential for corruption, and I don't want someone cracking open my skull and putting something in there.

Parker Dillmann:But if it was fully reversible, so you could take it out at any time?

Stephen Kraig:I don't know. I'd have to think about that. That's if it was well, once again, it would it would sort of depend on what fully reversible meant. Is it, like, you know, surgery plus 6 months of recovery? Or is it, like, I just go down to CVS and they just take a hammer and put a spear into your

Parker Dillmann:your They have a a Neuralink, like, you know, on a a SIM card on a phone, you put the little paper clip in it, it pops out?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:It's that, but in your ear?

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Right. Right. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I've you know, if it was something that was just absolutely temporary. If you could put a hat on and that hat could somehow interface with your mind and that would work So I Yeah. I'd be open for something like that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So you would not be down if it was like they installed neural ports. So that's what that that'd be a lot like the matrix where they have

Stephen Kraig:a Yeah. Where they have the thing where they shove the spear up your neck. Yeah. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So you could disconnect, but you still would have that port. Right. Right. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:What kind of connector is that? Because in the matrix, that thing was like a 5 inch spike. That thing

Parker Dillmann:I wonder if there's I wonder if there's a a a I triple e or a jadex standard for that.

Stephen Kraig:Probably. So I some nerd out there has written fan fiction about the protocol of how it connects to your brain. Oh, it and here there's a Wiki page about it. It's called a head jack.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, that's lame.

Stephen Kraig:What what's lame about that?

Parker Dillmann:No. It needs to be, like, I triple e 1483 or something

Stephen Kraig:like that. 1480 yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Actually, I don't know what that is. That is

Stephen Kraig:a It's way in the future. It has gone through multiple letters of revision, so it's like USB xf or something like that.

Parker Dillmann:I triple e 1483, standard for verification of vital functions and processor based systems used in rail transit control.

Stephen Kraig:And you were just spitting out numbers. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Just spat out a number. I knew it was gonna be a thing, though. Yeah. Alright.

Parker Dillmann:Let us know in the comments if you would get a Neuralink or like we have to come up with a cool name for it. A breaker port. So you can feed the podcast right into your brain.

Stephen Kraig:It's just the podcast. It's just the podcast. Yeah. Gotta start somewhere.

Parker Dillmann:Yep. Man. That'd be great. This is how you know this is how you know that we're real and we're not AI. We're not part of the dead Internet theory.

Parker Dillmann:No. We believe in it, but we're not part of it.

Stephen Kraig:We're fighting back. Are we really, though? Kind of.

Parker Dillmann:We're not digital voices yet.

Stephen Kraig:They I I'm sorry. I'm I'm still I'm still back on this Matrix plug because like, this this is an actual, like, interface that seems to cause, like, pretty severe pain when when connecting to it. Neo was in distress when they shoved that thing in his head. Like, you think they would have perhaps, I don't know, solved those issues?

Parker Dillmann:They're in a post apocalyptic world. They don't care. Yeah. A little bit of pain, puppies. Take a Tylenol.

Stephen Kraig:This thing is a massive spike. Oh, yeah. Okay. Well, I'm on just some random website of people. This this feels like a Star Wars.

Stephen Kraig:There is This feels like a Star Wars episode topic of is it possible to connect to the brain basically externally what they're doing or what they're Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:I mean, it'd just be like a connector that disconnects the probes like Neuralink is.

Stephen Kraig:See, I wonder.

Parker Dillmann:Those probes would be those probes would be inside your brain, and then there would be interface to your connector on the back of your head.

Stephen Kraig:See, here's the thing. Do you have to because the when the brain is developing at a young age, there's a lot of malleability to it, and a lot of the actual neuron connections have not fully been established. Like, you you and my sorry to say this, Parker. You're in my brains. They're done.

Stephen Kraig:We're on the downhill slope at this point. But if you were to install some kind of neural link connection on a child and as they grow, their brain is adapting to its position and what it needs to send to. It seems like that's the future where it's okay. You know, you get you are born and the first thing they do is, you know, crack the skull open, put a chip in there, and there you go. And your brain will just figure it out.

Stephen Kraig:Right?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Well, you say we're done. That's actually not true too. There's a lot of research in, like, stroke rehabilitation, and it's proven that our brains still remain not as flexible, but it is still pretty flexible, and

Stephen Kraig:it does I will obviously, I was making a joke, but I'm not saying that we're just purely degrading here.

Parker Dillmann:I mean, that's true. We gotta fight entropy every day.

Stephen Kraig:Well yeah. No. The the brain is remarkable in terms of being able to rewire itself when a serious thing has changed. It might take a moment, but it can do that. It's just the rate at which it does it is remarkable when you're young.

Stephen Kraig:Oh. But then again, when you're young, you're focusing on that in a way. So regardless, that doesn't change the rate or it doesn't change the how crazy it is that it does it so so rapidly.

Parker Dillmann:I think I'd get a port. Yeah? Yeah. As long as you can disconnect it, that's fine. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Well, yeah. So so the port as So it's it's it's more Ghost in the Shell then. Yeah. I mean, I guess in that show that they have, like, full they're cyborgs and stuff, but there's still, like, normal people that just have a connector on them that they can plug a phono jack into their a quarter inch plug Right. And and connect in.

Parker Dillmann:The one thing from that show that

Stephen Kraig:I would consider is the hands that break apart into a bunch of fingers and type it, like, a 1000000000 words a second.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. It's like you the fingers split in 4 fingers each.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. I love that there's so much engineering behind that for something. Is that necessary?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Because you could just connect to the computer.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. No. The whole purpose of that was a a tactile interface like a keyboard. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:It was designed to be fast at typing. It's like, why not just serial port in, and then you could be even faster than

Parker Dillmann:that. Yeah. I I guess it's kinda like air gapping yourself, though.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Right.

Parker Dillmann:Right. Yeah. That's probably more it now we're through crafting about ghosts and shell.

Stephen Kraig:I I think that's at the near the beginning of the movie, and and that's just one of those ones where first time I saw that, I was like, okay. That's legit.

Parker Dillmann:It's been a long time that I've seen that movie. I need to rewatch that thing. That that yeah. That's the original one. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:That's, like, 1980 what?

Stephen Kraig:No. I think that was that was in the nineties, I believe.

Parker Dillmann:Is it the nineties?

Stephen Kraig:95. 95. Yeah. 95. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, I so, a couple nights ago, Steve and I were chatting about Gundam, and the first Gundam series is older than you think. It's 79. Yeah. 1979. When I found that out, I'm like, oh, I I thought it was always, like like, mid eighties or late eighties.

Parker Dillmann:No. 1979. 1979. And it's still going. I mean, Gundam itself were not the original series.

Stephen Kraig:Well, yeah. Just Yeah. Yeah. And there's a lot of it. Wow.

Stephen Kraig:There's a lot.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. What and the other one is, It's with the shit. It's with the planes

Stephen Kraig:Robo tech

Parker Dillmann:yeah, is it Robo tech?

Stephen Kraig:Well the planes that become mex

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. That's Robotech. Is that Robotech? Or are you thinking Macross?

Parker Dillmann:Macross is Which

Stephen Kraig:is Robotech. Okay.

Parker Dillmann:Yep. You're right. I remember watching that show too.

Stephen Kraig:My my first girlfriend bought me all of the Robo Tech DVDs. I don't have that girlfriend anymore, but I have the Robo Tech DVDs.

Parker Dillmann:I will tell you, I would have married her. Can you give me her contact number?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Okay. Let's let's move on. Kinda rambled a bit about that. So I found out today via a tweet, the social the social media toilet as per last episode, that we have new tariffs here in the United States. Oh, yay.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Oh, yay. And this was a tweet by well, it was on Biden's account. Sure. So I don't know if he actually controls or tweets,

Stephen Kraig:but I very much doubt that he does any of that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. But he it was on his account. And, so we have a 25% new tariff on steel and aluminum raw materials, 50% on semiconductors, a 100% on EVs, and 50% on solar panels, and these are from China. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I was about to say this is tariffs specifically on China.

Parker Dillmann:Correct. So we were talking a little bit about before the podcast about this 50% on semiconductors, and Steven was like, oh, that's gonna jack up all the prices and stuff, but not necessarily.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Well and then and and when you see something like that and you see 50% tariff on semiconductors from China, there's this idea that's, oh, wow. That's really gonna hit me hard because, you know, China is the land of semiconductors, and we purchase all of our cheap semiconductors from them. But I did a little bit of research and got some information on the global semiconductor market share by country.

Stephen Kraig:And all said and done in 2024 or the end of 23, China controlled about 30%. I'm sorry. Not 30%. It's it's lower than that. It's closer to 17%, which is not a it's not the the number that was going through my head.

Stephen Kraig:I thought it was way way higher than that. Now and if we're talking about inexpensive ICs, if there's a high likelihood that necessarily And so this 17% number is not necessarily by volume. I think it's by total revenue effectively. So, you know, your more expensive stuff is most likely not going to be there. So, yeah, your cheaper stuff is going to be increased by 50% due to this tariff.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I'd love to see a by unit Mhmm. Percentage versus a by revenue percentage. Right. Because it's what, what United States was 40% as that article said of revenue.

Parker Dillmann:Well, it just says Close to 4%. The actual wording? What's the actual wording of that percentage?

Stephen Kraig:Well, I mean, it it says market share

Parker Dillmann:by Market share. So it is by it's and you actually go in one paragraph above, and it's talking about revenue. Yeah. So that is this by share is by revenue, not component raw component numbers. Right.

Parker Dillmann:So I'd love to see, like, a by component numbers, because I think you're right. I bet you a lot of the very inexpensive components, like the microcontrollers that cost, like, a quarter. I think, actually, there's a 10¢ microcontroller.

Stephen Kraig:Or, like, your el cheapo op amps or transistors or things like that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. What we would consider a jelly bean part nowadays.

Stephen Kraig:You know, I always called them jelly bean parts, but then I started this job and everyone my my newer job about a year ago, and everyone there calls them popcorn parts. So now they're not jelly beans anymore. They're popcorn for me. Popcorn parts? If they're Pringles, you

Parker Dillmann:just couldn't stop adding them to your board. No. That's it. Yep. That's actually bypass capacitors.

Parker Dillmann:Bypass capacitors are Pringles.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. For sure. Put them in a salt shaker and just shake them over the board. Yeah. Soar more than land.

Parker Dillmann:So, yeah, more tariffs. Woo hoo. That's all I'm gonna say about that.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I

Parker Dillmann:Okay. You got something. Yeah. Oh, I we talked we ranted too much last time about it, about this kind of stuff.

Stephen Kraig:So Yeah. Let's just leave it. It's just news. We're just saying this is what happened. So well, in in some more fun news, earlier today was announced the Raspberry Pi Foundation announced an m.2 hat is coming to the Raspberry Pi, and that's an m.2, hat, which is really cool if you ask me because this is one of the things that in my opinion the Raspberry Pi has been lacking.

Stephen Kraig:There's been mass storage options for Raspberry Pi, you know, you can do flash drives, you can do, external SSDs, you can do the SSD card, but there's downsides to all of those, especially with the SSD cards with this read write limits. But now there's an official hat that the Raspberry Pi offers, which is only $12, and that just sits directly on top of the Pi and gives you access to using m.2 drives. And that kind of completes the package in my opinion, because now you have permanent long term storage that is very fast and doesn't run the risk of corruption due to just read write cycles. Existing. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Existing. Right? Operating. That's the thing. A lot of times we have very pies are just if you're running it on SSD, it's a ticking time bomb.

Stephen Kraig:It will eventually fail and that's kinda scary. Right? Like I said, there's other options out there, but you always kinda had to just figure it out. Whereas now, an m.2 hat slap it on. Now, it's it's important to note that $12 is just a hat.

Stephen Kraig:You don't get an m dot 2 with that $12. That'd be insane. So so, you know, spend $12 on a hat and then whatever an m dot 2 cost nowadays $80 or something like that. They're probably even cheaper.

Parker Dillmann:They're actually cheaper than that now.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Well, I was looking for some just the other week and and the ones I were looking at was in that range. But for not that much, you can get a pretty awesome little computer now, especially with a Pi 5 because the speed is there and now you have storage that is there, like, we've said that every time a PI has come out, we're like, oh, it's there, but like it really feels like it now.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's a pretty cool product. It's $12, which is not bad. Yeah. But I wonder if it's made in China, and it's gonna be under that tariff.

Stephen Kraig:Did that tariff include PCBs and PC excuse me. PCAs?

Parker Dillmann:I don't know. Maybe Biden ran out of numbers oh, not numbers. Ran out of characters.

Stephen Kraig:Couldn't type anymore. Or there's other tariffs. They just didn't weren't able to type them all out.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So anyways, that's a few clues. I'm actually I have one on order now, so

Stephen Kraig:Oh, really? You're already snagged it?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Wait, do you have a pie 5?

Parker Dillmann:I have a pie 4.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, does this work with the pie 4?

Parker Dillmann:I don't know. Do I need to order a pie 5 now?

Stephen Kraig:I you know, we should look that

Parker Dillmann:It looks like I do. I think I do.

Stephen Kraig:I'm pretty sure that this is a pie 5 thing.

Parker Dillmann:Only. Okay. Let me order a pie 5.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Actually, okay. I would love when you get your pie and get all this, I would love for you to just maybe we can stream it just even between the 2 of us. I would love to see your thoughts on the first time it fires up and just playing with it for the first time and see if it's really snappy. Is it fast?

Stephen Kraig:Does it feel different, or does it just feel like another pie?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Okay. We can do that one as I finally get everything. Because the pie, I can order right away, but the hat is, like, back ordered everywhere.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And it just released.

Parker Dillmann:I have it on order whenever SparkFun gets it and and gets it back in stock. So alright. I have a personal project update kind of thing. A long time ago, what episode was that? Well, we we talked about reverse engineering tool sets, and this was like reverse engineering physical things, like measuring components and enclosures and figuring out how to make stuff fit together.

Parker Dillmann:This wasn't like reverse engineering electronics, I should say.

Stephen Kraig:I'm drawing a blanket about this.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Let me see if I can find that real quick. We talked about, like, dial indicators. It was like a dial indicator, but I had a 3 d printed end on it that you can measure radiuses. Man, that was that was a long time ago.

Parker Dillmann:Let me see if I can find it. Well, I have to go find it later, but there's another thing you should add to your toolbox For reverse engineering stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, what That is a flat. It's a

Parker Dillmann:flatbed scanner. Just like a classic scanner? Classic old school scanner. So I've been scanning PCBs and enclosures and also to basically bring them into CAD so I can measure stuff like locating holes and stuff. So it's like, enclosures that you don't have a drawing for.

Parker Dillmann:It's like, how do you know where that locating pin's at? And so you can scan so I have a process on this is you can Google this and people are like, yeah, that's normal. But maybe electrical engineers don't know about this yet, but you can scan stuff in. You can bring it in as a canvas into Autodesk, and then there's a calibrate function. So what you do is you scan it you scan in, let's say, your enclosure, and you also put in a ruler next to it.

Parker Dillmann:I like to use a PCB ruler. You scan that in, and then you can go in and measure you basically draw 2 dots and tell the software how far those dots actually are apart, and it scales your image correctly. And then you can go trace your image or yeah. You trace your image for your your outlines and that kind of stuff, but and then dimension them out so you can constrain the dimensions of the drawing, but then go back and measure some of those things on your actual physical one, the diameters of the holes. Go measure those and see if they match your scan that you did.

Parker Dillmann:Make sure everything lines up and that kind of stuff. But I've been mostly using this to this concept to scan in, like, gaskets for my the engine I'm working on. So this is gonna be, like, a new project. I've been working on it for a while, but it's gonna be a new feature set on the podcast. I have a really well, we talked about the checker, the 1965 Checker Marathon a long time ago.

Parker Dillmann:It kinda went on hiatus for a bit while I was working on other cars, but I've been working on it again. And more importantly, I'm working on the engine for it. And the engine, I'm at it's an old school Chevy, inline 6. 292 cubic inch displacement. It's, like, 4.9 liters, big engine.

Parker Dillmann:Originally, it was a carbureted with points ignition, really old school stuff. We're are going full on digital control with EFI, with multi point injection EFI, and so I have a I'm not doing the whole, like, open source controller or anything like that right now. Speeduino is like a engine controller that's open source. I have a MegaSquirt 3 Mhmm. Which is, like, one of the d I premium DIY controllers you can get nowadays.

Parker Dillmann:So I'm using that because it's, like, off shelf, and this is my first project of controlling an engine this way. But I'll I'm gonna do a podcast. We're gonna do a podcast episode in the future about all the different sensor but, basically, I talk about sensors and stuff and how you actually use those sensors. And we'll talk about it in kinda, like, the terms of, like, engine functionality and that kind of stuff. Should be a lot of fun.

Parker Dillmann:Nice. But I'm scanning in gaskets get back to this. Scanning in gaskets so I can draw brackets and stuff. So I'm like, oh, I need it to mount on this surface, and so I'll take a piece of paper and do a the Indiana Jones rubbing. The crayon rub?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. The crayon yeah. So I'm, like, so that way I can get the pattern of the bolt holes on a piece of paper

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Scan that in, and now I can draw that into, CAD and 3 d print out the bracket to test it out, and then I go send it off to get machined. Nice. So I'll say the 3 d 3 d printing engine parts like that has revolutionized that whole custom custom bracketry game, because it used to be, like, you'd have to go and find a machinist to machine your first prototype, and that costs just as much as your final one. Right?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And there's also the potential that you get it wrong.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, that that's the whole thing is you will get it wrong because there's gonna be something some clearance problem that you didn't think about when you start assembling the whole package. And so you 3 d print everything out, and you can't use it, but you so you can get all the fitment correct. Right. And then you can just turn it into aluminum or steel once, and it will work. That's like a superpower.

Parker Dillmann:I went through a couple different iterations of I'll post some pictures of it, of side covers for the engine. So it has this whole area where you can take the cover off to access the lifters that that's the part of the engine that, like, maneuver the valves off the camshaft. And the original ones are just sheet metal snap sheet metal with a gasket. I scanned in the gasket and scanned in the cover, and then I was able to make my own, basically, template of that. And that way I can make machine amount of aluminum and thicker aluminum so I can mount my ignition coils that I need to run the engine.

Parker Dillmann:And so because we're not doing old school ignition. We're doing modern one ignition coil per spark plug style, which is like a modern engine. Right. And I couldn't do that any other way because I think I got it right on the second print I did where I don't wanna know if I was trying to measure that up myself and then transcribe it into CAD directly that way. I don't know how many prints I would have to go through to get that right.

Parker Dillmann:Let alone if it was the old school way and I had to go tell a machinist to make me my first prototype, and you're talking, like, a couple $100 a shot easy?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Actually, probably more than that. It's probably, like, a $150 for a material, and then, you know, 4 hours on the CNC machine. So the

Stephen Kraig:the next step is how do you get those without having to go buy the metal or buy or pay a machinist? Like, how do you do that at home?

Parker Dillmann:Actually, there is a I haven't watched it yet, but there's a YouTube video about that process. Basically, like, 3 d printing metal to make exhaust manifolds, custom exhaust manifolds.

Stephen Kraig:I've seen just the other day, it was a filament that had metal in it that you would print and then you would center it yourself.

Parker Dillmann:I've seen that too.

Stephen Kraig:And it looks it doesn't look fantastic, but it does end up giving you a an actual metal piece that you printed yourself.

Parker Dillmann:I don't know about that part yet. It's mostly the prototyping that's the most expensive part.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Because actually getting it machined like, the final time, I'm okay paying, you know, machinist to run that. It's the prototyping because I I would've had gone through 4 or 5 different revisions of the side cover Mhmm. And literally just throwing away all that aluminum. Right. Right.

Parker Dillmann:Now they do you can get away with machining it out of Duralin or something like that Mhmm. As well, which is a lot less expensive than, aluminum, but and it's faster machine, but still not as fast as your 3 d printer on your desk. Sure. Right. So so, yeah, add a flatbed scanner.

Parker Dillmann:I have to find that old article or old podcast that we talked about it. Handful of PCBs, especially with 2 layer boards that you wanna reverse engineer. Man, just throw them in a flatbed scanner, scan them, and then just trace everything out. It's so, so easy. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. You I've done that before too, but I think the superpower is actually, like, reverse engineering enclosures and

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Finding Bolt patterns.

Stephen Kraig:Patterns. Bolt patterns. That's huge for that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I think that's gonna wrap up this podcast episode.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I think

Parker Dillmann:so. So let us know about would you glue a cell phone to your brain, or do you have a flatbed scanner that you use to would you glue a flatbed scanner to your brain?

Stephen Kraig:You just put items on top of your head, and then they just appear in your mind.

Parker Dillmann:Can can Neo is sitting in that chair, and he's just got a flatbed scanner on top of his head, and he just he has a a book of, like, how to do kung fu Yeah. And he's just scanning page at a page at a time.

Stephen Kraig:I know bolt patterns. Woah.

Parker Dillmann:Woah. I know kung fu. Show me. And with that, thank you for listening to circuit break from MacFab. We are your hosts, Parker Doman and Steven Craig.

Parker Dillmann:Later, everyone. Take it easy. Breaker for downloading our podcast. Tell your friends and coworkers about the circuit break podcast for Macra Fab. And, actually, we have a new review.

Parker Dillmann:It's like the first review we've had in, all forever. I'm looking up right now. Hold on. I wish I put this in the notes. Why can't they see the reviews?

Parker Dillmann:Ah, here it is. It's I think it's lkj741 Electronics Engineering. As a retired technician, Parker and Steven have kept me up to date with electronic design industry. We get bonus material including homebrewing autos and shop work. So thank you so much, Eld, for your 5 star review, and please give us a review.

Parker Dillmann:That's the first review we've had in 2 years, so that meant a lot when I finally saw that come up. So you have a cool idea, project, or topic you want us to discuss, let Steven and I and the community of Breakers know. Our community where you can find personal projects, discussions about the podcast, and engineering topics and news is located atform.macfab.com.