Set in 1929 at the Regent Hotel, Birmingham, Nora checks in under a false name. She is there to spy on the famed operatic singer Berenice Oxbow. But just like the Regent Hotel, there is more to Nora's story than meets the eye.

Purchase Hokey Pokey

(0:27) Introduction

(5:40) Childhood reading

(20:37) University and literature

(30:56) Fiction and Therapists

(38:14) Recent Reads

(51:09) Hokey Pokey

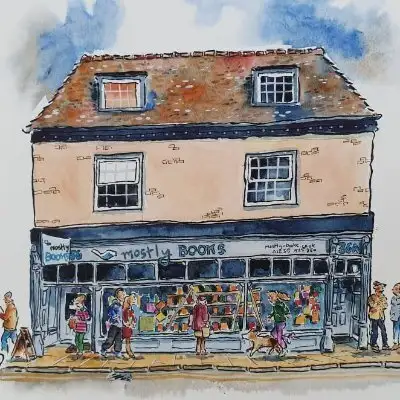

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a weekly podcast by the independent award-winning bookshop, Mostly Books. Nestled in the Oxfordshire town of Abingdon-on-Thames, Mostly Books has been spreading the joy of reading for fifteen years. Whether it’s a book, gift, or card you need the Mostly Books team is always on hand to help. Visit our website.

Meet the host:

Jack Wrighton is a bookseller and social media manager at Mostly Books. His hobbies include photography and buying books at a quicker rate than he can read them.

Connect with Jack on Instagram

Hokey Pokey is published in the UK by Bloomsbury

Books mentioned in this episode include:

Tom's Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce - ISBN: 9780192734501

Monsters by Claire Dederer - ISBN: 9781399715034

Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet - ISBN: 9781913393441

My Friend Natalia by Laura Lindstedt - ISBN: 9781631498176

The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter - ISBN: 9780099588115

We have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson - ISBN: 9780141191454

Mr. Fox by Helen Oyeyemi - ISBN: 9780330534697

Creators and Guests

What is Mostly Books Meets...?

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a podcast by the independent bookshop, Mostly Books. Booksellers from an award-winning indie bookshop chatting books and how they have shaped people's lives, with a whole bunch of people from the world of publishing - authors, poets, journalists and many more. Join us for the journey.

[00:00:00] Jack Wrighton: Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, the weekly podcast for the incurably bookish. We will be talking to authors and creatives from across the world of publishing and discussing the books they have loved. Looking for a recommendation? Then look no further. Head to your favorite cozy spot and let us pick out your next favorite book.

On the podcast this week, we welcome novelist Kate Mascarenas. To date, Kate has published three novels, including The Psychology of Time Travel and The Thief on the Winged Horse. Her third and most recent is the gorgeously gothic Hokey Pokey. Set in 1929 at the Regent Hotel, Birmingham, Nora checks in under a false name. She is there to spy on the famed operatic singer Berenice Oxbow. But just like the Regent Hotel, there is more to Nora's story than meets the eye. Kate, welcome to Mostly Books Meets.

[00:00:56] Kate Mascarenhas: Hello, it's lovely to be talking to you.

[00:00:58] Jack Wrighton: I was very excited when this interview sort of first came about when I was talking about it with your publicist because you're from Birmingham originally and and do you live in Birmingham now?

[00:01:07] Kate Mascarenhas: I do, yeah.

[00:01:09] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, you do.

[00:01:09] Kate Mascarenhas: Have done for quite a long time now, yeah.

[00:01:11] Jack Wrighton: You're back in Birmingham now, and even though I'm not from Birmingham myself, I grew up, pretty close by, so it was always kind of growing up, it was the sort of the big city to me, it was Birmingham that you went to, and I've got a lot of love from Birmingham as a city, so to see it kind of set there in the book, and to know that you were from there, I was sort of, I don't know, it was quite excited.

[00:01:32] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, I'm really glad about that, and it's nice that, because Birmingham's a bit undersung, so I'm glad that you had that reaction to the setting. that's lovely.

[00:01:40] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely, and I did sort of one of the questions I did have was, is that sort of part of the thinking? Because really I feel before maybe something like, I didn't know, sort of Peaky Blinders, maybe Birmingham in terms of kind of. being known as a place where you might sort of set, you know, different stories and things like that, it doesn't come up as often. And was that kind of a thinking for you for setting Hokey Pokey there?

[00:02:01] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, because with my previous two books, the first one was set over a variety of different areas, and then the second one was set in Oxford, and I've had it in mind, setting something in Birmingham for a while, and there were certain reasons why I thought it might work thematically for this story, but also, a big part of it was just that I wanted to write about where I'm from and, you know, Birmingham doesn't get to see itself in books that often, in contemporary fiction, you know, there are a few writers doing good work. But yeah, we are underrepresented, so it was nice to do that, yeah.

[00:02:36] Jack Wrighton: Yes, absolutely. The joy of, I don't know, being a writer is, you know, you can see that sort of gap and think, well, you know, I can bridge that, you know, I can do that with my work and sort of bring Birmingham more into kind of the literary, scene, and am I right in understanding, so you were born there, you spent some time there, but then you've sort of moved around and come back.

[00:02:54] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, I didn't move too far. we spent my teens just north of Manchester in Oldham. I, we lived there from when I was 14 and then, I left when I was 20 and I went to university in Oxford and then came to Birmingham, immediately afterwards for family reasons really and have stayed here. Yeah, and it's done quite well by me so I don't really have any complaints.

Yes, I'm aware I don't, we don't necessarily want to make the whole podcast talking about how great Birmingham is, but with Hokey Pokey now being out there in the world, obviously that, you know, this is your third book, so I imagine, you know, it's kind of a process that you've got used to, but is that still an exciting time, a nervous time for you as an... I think because my second book came out literally it was like two days before the second lockdown when all of the bookshops shut and, a lot of the hard work that we'd put into it, we were still able to achieve a fair bit, but it wasn't the sort of launch for that book that anybody involved in producing it had hoped for and I kind of feel the aftereffects of that a little bit actually, I think certainly, my, sort of, attitude in the run up to this one was much more, sort of, cautious than I think it would otherwise have been. Not because I thought that there was going to be anything that happened, but I think it just sort of changed my attitude subtly. That, you know, sometimes things come up that are beyond your control and you just kind of have to deal with them. But,it's been enjoyable seeing it go out there and actually in terms of, you know, celebrating the launch, it has meant that I've also got to see some people that I, you know, I haven't seen since before the pandemic.

So that was actually a nice little reunion opportunity as well. In some ways it feels very positive that, you know, we're kind of. Coming out of something that, you know, is difficult for all of us, and, this is the sort of rounding off of the project that I was working on for most of that time.

[00:04:48] Jack Wrighton: Yes. Yeah, absolutely, and there must be, is it fair to say there's something quite freeing in that attitude of kind of, you know, after that experience, which, you know, for any creative can't be easy, you know, you have this launch and then this kind of world changing event happens. But is it quite sort of freeing now to, you know, kind of have that attitude of like, well, you know, these kind of big out of my hand situations can happen and so there's no point kind of resisting that.

[00:05:15] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, I think so. That's how I've experienced it anyway, and there are kind of, I suppose, in terms of, you know, all of the work that I do around it as well. it's, I would do things that I think work for the book and work for me. But I also... I know that in the big picture, in the grander scheme of things, there are aspects of it that are not going to move the needle and I think it is quite healthy to have an awareness of that. Yeah.

[00:05:40] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, absolutely. But in terms of you and your relationship with words, from a young age, were you always kind of interested in stories? Were you always a reader or did that come later on for you?

[00:05:50] Kate Mascarenhas: No, I was always a reader. I learned to read early and both my parents were big readers as well. while I was at primary school, my mother went to university, which she hadn't had the opportunity to do financially before that, and she trained in librarianship. So when she was qualified, I mean, I'd always use public libraries, but it meant that I was in that library pretty much all the time that I wasn't at school and my dad was a big reader and he read so much without sort of any prejudice. It's like he had his preferences. He liked the modernists, he liked reading European novels in translation, but he would read, you know, a crime novel or a romance novel or anything with an open mind. and that was a really nice sort of attitude to be around in terms of my own reading and they were quite, I mean, I think, you know, people are more cautious now about children reading above their age range, I think, and my parents would have, sort of, if they saw me reading something unsuitable, they would have taken it off me. But they did actually turn a blind eye quite a lot, I think, to me, just sort of subtly taking books, you know, from the library or, you know, or from the shelves that might have been a bit sort of above my comprehension and I think that was good for me, actually. Yeah, so I was always reading and much more of a reader than a sociable child. I was a bit of a loner, really. I had friends, but I was always sort of much happier just to sort of slink off in my book than, you know, to sort of get involved in like rambunctious play or anything like that. I was very much sort of in my own little world.

[00:07:22] Jack Wrighton: That's a story we've definitely heard before on the podcast and people sort of saying, Oh, you know, I was, yeah, at school, I was reading a lot, and, you know, but yeah, a very particular sort of image is painted. But I think that's great about your parents being very, sort of free or at least kind of understanding if it was kind of turning a blind eye to you kind of reading above your age range because that's actually a conversation we regularly have within the shop is you know if a kid comes up with a book that we feel is slightly you know older than their age range you know do we say to the parent oh we feel that's or do we just sort of leave it and go well you know they've made that decision because yeah I've always felt that, you know, reading will interest you.

I spoke to someone once from the World Book Day organization. They said they did a study and actually one of the best things for to get kids into reading is to just allow them to read, you know, whatever if they pick it up and say, I'm interested in this, you know, to let them read. And of course, you know, I'm sure as like a parent or guardian, you know, you want certain, obviously certain restrictions on that.

But I think it can lead to a great sort of exploration and finding out kind of early on what you like and what you don't like, because it's such a, important period for, I suppose, kind of working out what your taste is. Whether that's a really broad one or a more narrow one. But it sounds like, did you sort of develop your father's kind of wide interest in reading.

[00:08:44] Kate Mascarenhas: Yes, I did, and I think the other sort of thing, I suppose, that I miss about my childhood reading, because it isn't possible once you're out of that developmental stage, really, but just that experience of, encountering something where quite often my actual, my literacy was ahead of my comprehension. So, just that sense of feeling like I was in a world that I didn't quite have the life experience to understand yet, but, you know, almost being in touching distance of it, and just sort of be sitting within that sort of sense of unknowing, really, was very exciting and, you know, it's not something that I think I can capture the same way as an adult.

So yeah, so that, that's kind of what I think about when I think about my childhood reading, really, and yeah, I mean, I moved on to adult books when I was about, But I mean, up until that point, I remember when I was very small, like, my dad was an Irish speaker. So he would try and get, Ladybirds used to do translations, I don't know whether they still do if they're well loved tales, and he had ones in Irish for me.

So he would like, sort of read those with me, and I would pick up like little bits of vocabulary, and little bits of the grammar. So, you know, I have like a really rudimentary, sort of at a child's level, I know like my Irish colours and how to say basic phrases, that kind of thing. But I have, I think I had the Elves and the Shoemaker in Irish and that always felt like a really nice connection that. although he was sort of away from his family, he was giving me something of where he was from. So I remember that, and then kind of when I was older, I didn't really have favourite books as such, and there are some things that I think, I guess what I think about now is which ones I've remembered since, and which ones I've thought about most often since, and One of those is a book called Cora Ravenwing, which is by Gina Wilson and it was written as a children's book in 1980, but I think about Faber released like a, they republished it as in a very sort of sleek, minimalist looking adult edition. Which,which you can get. But what I remember about it, because, I mean, I'll just briefly summarise what it's about, but it's set in the 1950s and it has a very, traditional setup for a 20th century children's book, which is that there is this little girl who's from Birmingham, actually, and she moves to a much smaller, close knit community because her father's job changes, and the first person she meets is this other little girl called Cora.

They are about nine or ten, I think, and, she's playing in the graveyard, and there's something sort of slightly otherworldly about Cora, you know, she spends a lot of time amongst the dead, she explains that, you know, this is where she spends a lot of time, her father works there, but also her own mother died when she was born, and she's, you know, she's quite sort of intense, like she writes a lot of nature poetry, but Becky's really drawn to her and really likes her, and then runs into problems, because when she meets the other children in her class, who are very welcoming and really want to befriend Becky. They say you can't go near Cora, like she's an outcast, like she's completely ostracised, and Becky can't understand why, because it seems totally irrational and it's actually quite a superstitious. Sort of, because Cora's mother died in childbirth, they've kind of held her responsible. So, really this story is Becky trying to spend time with Cora secretly, while not sacrificing the connection that she has to, you know, her other new friends and also trying to settle in, into somewhere that, you know, she's new to. You know, I feel like it's a nice sort of... twist on the idea of, you know, somebody coming to a new place and getting bullied, that actually she's the person coming in and saying what on earth is going on here? This doesn't make, you know, why are you know, why are you cutting this girl out for something that isn't her fault?

And I guess, thinking about it now, I mean, I've read it, re read it, sort of fairly recently, sort of within the past few years. It just, it has a really nice handle on loneliness and just like some of the injustices of, you know, being at that age and not having very much control over your life, you know, that as a child you do have to submit to sort of, because within the story as well, it's like all of the adults are active participants, you know, in fact there's one who kind of ring leads it in a way, so it's not even that it's sort of confined to the school, and if I think about other books that You know, I remember from childhood, they do quite often have that kind of focus on loneliness.

I really liked Jenny Nimmo's, Emlyn's Moon, which is the middle book of the Snowspider trilogy. And that has a similar sort of storyline, really. There's a very lonely boy. In that, he has quite an eccentric father. and you know, the narrator has this sort of developing friendship with them. And, just before Christmas, I also re read, Tom's Midnight Garden.

Which, I don't, because it has such a strong sensual friendship, I don't think of that as being about loneliness. I was just really struck on this last reading, at how in their respective worlds, both Tom and Hattie, you know, as they're sort of seeing each other, sort of, you know, as he travels into the past. They're so isolated within their respective worlds. He's away from everybody that he knows well. She doesn't really have a very secure place in her family, and there are all these really poignant conversations, you know, where they're discussing which one of them is real. That I thought, these are actually much more painful than, you know, I'd remembered them being. I think in terms of stories that, you know, I have an attachment to, that seems to be a bit of a common theme. Yeah.

[00:14:19] Jack Wrighton: Oh, it's these kind of lonely, sensual characters. Yeah.

[00:14:23] Kate Mascarenhas: I think it's, yeah, it's something that, yeah, that I can see as a thread running through, I suppose. Yeah.

[00:14:30] Jack Wrighton: It's just so wonderful to see what's available out there for children to read and dealing with, you know, really, you know, really difficult things like loneliness, which I think is something, you know, probably, you know, a lot of children do, do experience. I always say I would probably never be, certainly a teenager again. I don't think I...

[00:14:46] Kate Mascarenhas: No.

[00:14:47] Jack Wrighton: It's not a period of my life I'd ever want to repeat.

[00:14:51] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, and it's interesting that, so my PhD was in psychology and literary studies, but I was looking at how certain stereotypes are constructed within children's books. So I've kind of, I've looked at it, you know, I mean, I finished it sort of 10 years ago, but. During that sort of period where I was working academically, you know, I was looking at children's books all the time through that slightly different lens and, you know, looking at how they've sort of, how the idea changes over time as well over what is suitable for children and, you know, there are phases sort of, of more serious subject matter or sort of, I mean, a lot of Cora Ravenwing is really quite bleak and I kind of, I just, I think that. You know, it's not that there aren't, sort of, more hard hitting books for, children these days, but I'm quite sure that the publishing conversations around them must sound very different, than they did, sort of, 40 years ago. So that's sort of, that's sort of changing picture of how we think of the child reader. it's really interesting to me as well.

[00:15:48] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely. Yes, it's funny because I feel when you come across maybe children's books from, let's say a time where maybe they're a bit more, or you know, certain things aren't to be discussed or mentioned, that there can be quite an uncanny element to them, because I don't know, because it seems like they're sort of actively trying to avoid certain kind of subject matters or certain kind of emotions.

So they can have this almost slightly kind of eerie quality to them, and did you know, as a reader, so did that continue into your teens? Did you ever have a sort of, not a break from it, but a period where you didn't read as much or has that remained pretty consistent?

[00:16:24] Kate Mascarenhas: No, I was a bit of a book junkie, really. I was just... I did sort of, I mean, I moved, I mean, as I say, at about 12, I started reading books for adults. Partly because there wasn't quite, there were books for teenagers, but there wasn't a YA market in the way that there is now at all. so a lot of the books that were aimed at teens, I kind of already sort of read when I was like sort of 10-12 and, yeah, and I was kind of ready to move on to, you know, books that were aimed at adults really, and, I mean, I guess I remember reading, I read the Buddha of Suburbia when I was 13, and that had a huge impact on me actually, because it was kind of, it was the, it was actually, it was, I think it's the first, instance of bi rep, that I'd seen in an novel, so that, that was actually really important to me and I mean what I do kind of remember though is I, throughout my teens, I read a lot more men than women and I didn't even think about it , it was just kind of what was there, and, you know, I kind of just sort of accepted without really questioning that was what sort of the literary landscape looked like and it wasn't until, you know, I guess, To some extent when I got to university, but certainly more in my 20s that things started to even out, yeah.

[00:17:42] Jack Wrighton: It's interesting about the sort of, you know, representation aspect because I feel that's a, you know, very common theme with most readers. I mean, people we've had on the podcast, but just readers in general can sort of remember the first time that in a book you saw something that previously you hadn't come across in a book and whether that just sort of reflects the kind of the world around you or an aspect of yourself. It really sticks with you, doesn't it? I certainly find.

[00:18:06] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah. And some things as well, it's easy to, sort of, there are some things that I read at the time that were really important to me, but I now have some ambivalence, I guess, or they're quite complicated feelings. I was thinking a lot, because of Martin Amis' death recently, his books were really important to me when I was a teenager, because he was such a brilliant you know, just in terms of constructing a sentence, you know, they were so perfect. But also, he expanded my understanding of what novels did, and, you know, I think the Rachel Papers was the first one of his that I read. Which, you know, when you read it as an adult woman, it's a really complicated read. Just because it's quite hard inhabiting that sort of adolescent boy mindset. When he says quite a lot of hostile things about women. But I still really treasure it, even though, you know, I understand that by many measures it's problematic, as, you know, as we use that word now.

[00:18:59] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, absolutely. I think many of us are now sort of having the conversation about, I don't know, kind of favourite classics or books that we read when we were younger, or even other art forms that we sort of consumed that now you realise, you know, sort of looking back, and you think, oh, goodness, that was really, you know, I didn't really see that at the time, but now that really stands out as something that really, it hits a certain part of you, a kind of, it's like a snag, and you feel like, oh, like, what's that doing there? And you have to sort of, you know, balance the kind of enjoyment maybe you received at that when you first kind of consumed it, and the fact that you realize, you know, it's, it's kind of more complicated than you first realized.

[00:19:37] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah. I've just finished reading the, Claire Dederes book, the Monsters, yeah. Which is on this subject and what you do with those feelings. and,I mean, I didn't agree with all of her examples of everything she was saying actually, but there were some parts of it that I thought were, you know, were very beautifully considered. Just the sense in which, you know, you have, like this sort of stain that creeps through, things that you might have a great deal of love for, that you can't sort of separate out certain things. But, you know, the sort of beauty washes over you as, as well as, you know, the difficult parts and, yeah, I found that quite a moving read, really.

[00:20:14] Jack Wrighton: I've got, when you mentioned that you probably saw my ears, prick up because I recently got a copy of that because I think it's such a, it's such a interesting, yeah, interesting subject matter. So I'm looking forward to, and now I've heard what you've said, yeah, and particularly I'll think about that when I'm reading it and so yeah, kept reading until you're, into your teens and I'm so sorry, remind me of what you studied at Oxford again. It was...

[00:20:37] Kate Mascarenhas: So I actually, I studied English, literature and language, and much later on I, I, switched to psychology sort of, when I was older. so I, I got sort of a foot in each of those camps, by the time I started writing novels. But yeah, I did my degree at Oxford and what I recall, I enjoyed my third year academically because I could, I kind of gone through, the degree was chronological, you sort of, you were allowed to read whatever you wanted, as long as it was published within the specific dates for the module, which was, incredibly freeing in some ways. I mean, you know, there are more prescriptive, I think, and it did mean that I had a really good sense of continuity. By the time I had sort of, when I got to the stage where I was thinking about what I wrote for my dissertation and everything, I felt like I'd got a really good basis for that.

But,I was actually quite miserable as a student for those first couple of years in terms of my work because I'd gone from sort of feeling quite comfortable with A level where, you know, you have a very small number of texts and you really drill down and you get to know every little aspect of them, and suddenly it was this much, such a quicker moving, getting an idea of breadth, but sort of not getting that time to sort of really dedicate to each book and I found it I just sort of quite disorientating I think for the first couple of years I was there and didn't really find my feet in terms of you know, I had, socially was all right, I had friends and everything but in terms of my actual studies I didn't really find my feet until really my last year

[00:22:09] Jack Wrighton: I can imagine, particularly, I mean, I'm aware as someone, you know, who didn't do an undergraduate at Oxford, I maybe have a, I don't know, a slightly sort of fictional idea of what that would be like in my head, but I imagine it to be very intense and actually it would make sense to me that your third year is only really when everything sort of, you know, comes together, sort of starts, starts making sense.

Yeah, and I mean, they have, you know, they have beautiful libraries, which I still use when I have the opportunity, and you know, all of that was fantastic. But yeah, I mean, it's sort of... It was an odd time, I think, because I kind of, my little social circle, we were, you know, we were the kids who sort of were, you know, we had state school backgrounds, or, I mean, actually, I did actually, you know, I went to a whole variety of schools, I went to several different ones, I was very used to sort of switching, but the kind of demographics of Oxford and felt quite alien to me and my housemates. So that was kind of something that also coloured my time there, really. Absolutely. But nice that you had that. I think that's so important. Nice that you had that network there of people that could empathize with that. Because I think, yeah, you know, talking about kind of those characters that, you know, are sort of lonely. That would be a very lonely experience is kind of finding yourself, you know, with people where you think, well, do you get kind of what this is like for me? And, you know, they don't. So it was nice that you had that.

[00:23:32] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah.

[00:23:33] Jack Wrighton: And do you mind me asking, just out of interest, seeing that it was English and it's kind of on topic, what your final year thesis was on? Did you look at a particular period, or...?

[00:23:42] Kate Mascarenhas: It actually, it was on children's books. I was looking at the, I was looking at the writer Lucy M. Boston and her Green Knowe series. I mean, people sort of in their 40s might remember one of them was televised by the BBC as The Children of Green Knowe. Like a slightly spooky story set in an old Norman sort of house that, you know, this little boy goes to stay with his grandmother and he sort of plays with the ghosts of all the children who've lived there before.

So there's,there's several of these books, and I was looking at how, Lucy M. Boston was very concerned about nuclear war, so it's an undercurrent to a lot of the sort of stories that she was telling within this series. They kind of skirt around, I suppose a bit like you were saying before, where they don't mention certain feelings in certain periods.

but it was still shaping,the stories that, that she wanted to tell even though she, you know, she wasn't that explicit. Yeah, so, gosh, that was, I did that, 22 years ago. Yeah, so, a while now.

[00:24:40] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, it's scary, isn't it? I was thinking, I was realising the other day that my undergraduate was, Further in the past than I'd initially thought. And yeah, it's scary how time creeps up on us. So we've talked about things that you read when you were younger and things that you were looking at a university. In terms of sort of more, more recently, do you find you have time for reading or does your own work take up a lot of that time?

[00:25:04] Kate Mascarenhas: No, I still read a lot, but it tends to alternate, so I'll read less when I'm sort of heavily into edits and redrafting, but, then there'll be sort of periods while I'm waiting to sort of hear back from, you know, various sort of publishing contacts where my reading will go up much more and, yeah, I mean, at the moment, I'm on a bit of a tear currently reading books that feature therapy in some way. I mean, this is, I mean, therapy comes up sort of in my novel Hokey Pokey, which I'm sure we'll come back to. But I'm really interested in how, and I guess like the most recently published one that I've read lately is Big Swiss, which is kind of therapy adjacent.

It's got a really nice premise. The main character is a transcriptionist. Which is actually a job that I've done in the past, and she transcribes therapy sessions, and she listens, she doesn't know what these patients names are. She doesn't know what she knows is what she hears on the file. And there is one particular woman who she gets used to hearing and as she, transcribes these sessions, she falls in love with her. Just through, sort of, hearing these recordings. Which is just, such an interesting and inevitably they meet, but where the tension of the story from that point, stems from is that the patient doesn't know that she has this insight into her inner world.

She's not aware that she's heard all of these transcriptions. That's not something that, she's clued in on. So that there is this kind of conflict from then on between the transcriptionist knowing that she has all of this access to, you know, to her thoughts and feelings and private life and the patient doesn't.

So, so that's kind of the one that's most recently published, but... I'm just very interested in how stories that, that feature therapy, they do tend to be about these transgressions and the therapists tend to be, you know, so often then portrayed as frauds, which is pretty much what I did with Hokey Pokey, or at the very least, even if they're doing something that, you know, the patient ultimately feels positive about, or, you know, that therapy is some kind of route to healing, there are boundary transgressions, and what I find so interesting about this is if you look at, like, other caring professions, like other kinds of doctor or nurses, they are represented in fiction. You know, there are some examples of monsters, but it seems to me that the spread of representation is much broader that you have, you know, you have very good, sort of, people, sort of, fulfilling these roles in novels and short stories. Whereas, I find it really hard to think of a therapist in fiction, who acts ethically, actually, I, I guess, is what I'm saying. and I'm very curious about why that is. I mean, I've read... Lately, not quite as recently as Big Swiss, but Case Study by Graham McRae Barnett, which is about a kind of R. D. Lang type figure and I absolutely loved it. I just loved how it's made up of kind of, uses sort of faux documentation and nobody in it is quite as they're representing themselves. You never quite have a handle on who, what people are really like within it, and I loved that uncertainty and published right about the same time there was My Friend Natalia by Laura Lundstedt, which is entirely set within a sequence of therapy sessions told from the point of view of the therapist who, there is something very dodgy about their credentials and, this patient, Natalia, she comes to therapy saying that she can't stop thinking about sex and that the therapist has this experimental method to use with her, and, I should say, actually, all of these books that I'm talking about are quite comedic, which is another thing that's interesting. That it's like, it's something that sort of gets handled a lot in a kind of humorous sort of satiric way and, you know, but again you have this sort of therapist who isn't really, you know, what they're presenting themselves as, and then going much further back, well it's 20 years, and it's relative isn't it, but, I was thinking about, Aiding and Abetting, by Meoriel Spark, who's a writer, you know, I've read a lot of, and that novel, I mean, it was right at the end of her career, it's the penultimate one, and it isn't where I'd start if I was, you know, I was recommending, sort of, to somebody who was completely new to her, but it is really interesting on complicity, and it involves somebody who says she's a psychiatrist, who's very sought after for therapy and she's approached by this man who claims to be Lord Lucan. This is at the start of the book, and she's quite surprised by him saying this because she already has a patient who claims to be Lord Lucan. And the kind of the ensuing sort of comedy and discussions about how people enable sort of, atrocious things, you know, in the case of Lucan, that, you know, he'd killed this woman and as an aristocrat, you know, people were kind of enthralled to that. his friends and associates helped him get away, essentially. So it's, you know, it's an interesting, it's an interesting novel, but I do wonder about how, you know, I've met a lot of therapists. I've been treated by therapists. I've worked alongside them sometimes in various capacities and to a person, they were well intentioned, you know, they didn't necessarily always do the right thing, but I don't think that... It's interesting to me that they're so consistently awful in books, and I'm not sure whether... I've kind of wondered whether some of it is that historically they've had the power to lock us up. Whether it might be, sort of as simple as that. I kind of wonder whether we might be putting them in a slightly parental role and there's all sorts of negative feelings sort of being carried over from, you know, sort of particular sort of family dynamics that are getting played out as well, and so I haven't got any sort of firm conclusions on that question yet, but it's something that I'm thinking a lot about at the moment.

[00:30:56] Jack Wrighton: It is interesting. Yeah, I've also read Case Study. So that's the only real example I can think of. But, yes, when I do think just in, in fictional stories in general, yes, they don't come off well, do they? They've got a bad rep, therapists or psychologists, and yeah, that is really interesting to think about, yeah, why that is. When I also feel, I don't know, I feel in everyday conversations, people sort of... talk about, you know, more so these days. I think people talk about, oh, you know, therapy being a good thing, kind of, you know, going to a professional in order to kind of work on your mental health or kind of talk through your mental health.

So it's also interesting that exists at the same time as all these fictional people who are like, you know, either just, yeah, as you said, like, either completely monstrous or at least a kind of crossing boundaries that shouldn't be done. Do you think it's to do with the, maybe the intimacy of something like, sort of therapy or that, that relationship that, you know, you're in sort of close quarters, you're talking about very sensitive things that people, that just, in a fictional sense, that just makes people think, oh, well, you know, maybe this is going on or this is going

It seems plausible, doesn't it? I kind of, I don't know. It's like at the sort of apex really. You've got like Hannibal Lecter who sort of eats his patients and it just, that's a lot, you know? That is indeed a lot, yes.

[00:32:17] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah. Yeah, and,I just, yeah, I mean I can kind of, it's like in terms of that intimacy that certainly accounts for why you get sort of books like I mean, I haven't read The Prince of Tides for years and years, but I suppose I think of that as an example of a kind of book where, you know, therapy is,it's, within the story, it fulfills this really important function for the main character, and it is how he recovers. But he does have an affair with this therapist like, you know, she, so if, and that kind of, you know, It feels quite shocking to me, so I can kind of, I can see in terms of the intimacy of the relationship why it's the obvious place for that particular outcome in stories that, you know, you would naturally think, well, that's where the drama is going to be.

That's how you create like a good story. You go from that particular angle. I think there are kind of other sort of things about therapists being frauds comes up so much and that I just, I find it, and I do wonder if that's a little bit of a residue of the stigma of mental illness actually, because it's quite close to saying it's like when she starts saying, well, all therapists are frauds, it's like you're just one little step away from sort of questioning whether mental illness is something that's also a real thing and I do wonder whether that was a factor with Spark, actually. I mean, she had, it wasn't that she didn't think that mental illness was a real thing, but I think her sort of, her take on it was, you know, she had a very sort of religious framework for understanding it, for one thing. So, I wonder how much that, because it's not even, Aiding and Abetting isn't even the only book that she has a therapist in. It's something that sort of crops up in some of her other stories. So it was obviously something that she was drawn to use as an idea.

[00:33:55] Jack Wrighton: Yes, it's definitely something that a lot of writers, you know, again, creative, sort of, you know, feel quite happy to put in their books, whether it is as a kind of active part of the plot, or kind of, you know, maybe just, in the background, and I'd be interested to know... you know, with certain professions, if you put that in a book, people would assume, well, you're gonna have to do a lot of research to know how that works.

You know, if someone writes a book in which, I don't know, one of the characters is an astronaut, there would quickly be conversations about that. Oh, well, what research did you do? But I don't know if it would be the same with people who write about, you know, therapists or psychologists or, you know, people who deal with mental health, which is interesting, because... I don't know, from your perspective as someone who knows more of that, who's in that world, you know, do you feel you come across sort of examples where you think this has just purely come from their head, there's kind of been no framework for how this is represented?

[00:34:50] Kate Mascarenhas: It's funny, isn't it? Because, you know, I'm kind of in the camp of, with Hokey Pokey, because it's a horror story and it has sort of fantastical elements. I did actually, I did research quite carefully what sort of, you know, what was going on at the time, and there were certain things that we would say is transgressive now that happened more often in the 1920s, so people treating their families, people marrying their former patients. It wasn't that, you know, it was thought to be a good idea, but it happened with greater frequency and didn't receive quite the reactions that it would now, and I suppose, you know, in that sense this being set in an earlier historical period was quite useful to me that I didn't sort of have to worry quite so much about if I have sort of my therapist doing some really awful things that she does do some very awful things. Is it going to be actually grounded in the reality of what people's experience of therapy currently is?

But I mean, the other thing that sort of, in terms of resistance to, and questions that might get asked, I sometimes feel a bit uneasy because my PhD is in psychology, and because I'm a chartered psychologist. There's this sort of, what I kind of have to deal with is people's expectation that, their idea of a psychologist is somebody who works clinically.

So, I have to kind of be extra clear sometimes, I'm not that kind of psychologist, because people expect what I'm saying to have authority, and I kind of feel like I have to take, you know, some effort there to be like, no, this isn't actually coming directly from my life experience, you know, and I do wonder sometimes whether possibly on the publication journey, because of that disconnect. Where people would think that I might have been directly involved in therapy in a way that I haven't been. That, you know, I have to be wary that they are asking me enough questions, I suppose. You know, the problem that I more often encounter is that people assume I'm going to be an expert when actually there are things that I need to check and the people that I need to talk to and, books that I need to look up and that whole sort of process of being accountable.

[00:36:52] Jack Wrighton: Absolutely, and I think, yeah, that's fair, because even as I was asking that question, I was aware of, you know, I feel, you know, maybe it's fair to say I sort of reflect a kind of general public's understanding of these things and kind of, you know, we have these words in our head and what they mean, but what we necessarily picture doesn't line up with the reality.

So I'm glad I asked that so you then you could say, and it is, yeah, interesting that relationship between these kind of fictional characters. How the public perceives these things, and then the reality, there's kind of a, an interesting triangle with a lot going on.

[00:37:24] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, and there's always, I think with any, the representation of any profession, people are aware of, you know, when their own job comes up in fiction, of all the things that it gets wrong, and, you know, I think although I'm sort of talking about therapy as a special case, I do know that like, I mean, my husband's a photographer.

And we always have a laugh when they come up in like some TV series, they're always so incredibly sleazy, you know, they're

[00:37:47] Jack Wrighton: yes. . Yeah,

[00:37:50] Kate Mascarenhas: You know, so it's like there are these sort of stereotypes associated with particular jobs I think and my mum would always complain about librarians being very sort of boring and sort of pedantic and you know having a very sort of typical sort of physical appearance when they come up, sort of in stories as well.

So, you know, I think everybody has their own little sort of bugbear about how their work gets portrayed.

[00:38:14] Jack Wrighton: Yeah. Absolutely, 'cause yeah, don't get me started about how book setting is perceived and discussed because yeah, we could be here for a very long time, but yeah, it's, yeah, always an interesting thing, sort of how different kind of professions are depicted and why that is, and why they sort of loom, some loom kind of more in the imagination than others do. The sort of final question or kind of book for you to kind of recommend to our listeners would be a sort of, a kind of all time favourite of yours or one that you feel has had a kind of big impact on you.

[00:38:44] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, I mean, this is kind of, I don't have favourites in the sense that I might give a different answer on a different day. today I'm going to say The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter. I love how dense and sensory the imagery is in it, and I just, I mean, I think with fairy tales generally I like the sort of sense, that sort of slight sense of dislocation from where you are in time and the fact that she has, you know, her characters using telephones and, you know, going off to sort of historically very specific wars, but you know, they are in this land of the fair where, you know, you're slightly disengaged from those usual sort of anchors of time and place and, you know, I think she handles that so well and also, I mean, it just is a, it is kind of general point. The actual, the title story in that is like a long, short story, but it's a length I really like, like I love. I love short novels, I love novellas, you know, my other favourites are, you know, I love Shirley Jackson's We've Always Lived in the Castle, I love The Prime of Miss Jean Brody, I really like Mr. Fox by Helen Oyeyemi, you know, just sort of, very sort of condensed storytelling I guess, with strong voices and a sense of humour, that's kind of where my favourites lie.

[00:39:59] Jack Wrighton: I'm glad you said that because, me and a colleague of mine, we've always joked about there being, which sounds almost sacrilegious, but there being almost like an ideal length to a book, and we sometimes joke by sort of holding books up and going, yeah, that's a good size of a book. But it's interesting because I think different people engage with different, you know, different lengths, so I would, you know, I would certainly say as, you know, someone who, you know, who is dyslexic, that kind of sometimes a large book can be off putting, and sometimes I pick it up and then I start reading it and I'm like, once the story's got me, fine. But, yes, there can be a real joy in a kind of a shorter read and they have their own kind of intensity, their own power. I feel, you know, we talk about books, but I feel, yes, stories of different lengths. they're always doing something slightly different. They kind of exist in their own specific kind of realms, and I think, I think certainly with The Bloody Chamber, I also love The Bloody Chamber and yes, it's such an interesting length because it's not quite a short story. Like it crosses over a certain boundary.

[00:41:02] Kate Mascarenhas: It feels strange in that sense actually as a reader. It's like you do subconsciously get used to things being a particular length. It's like, I think, you know, if you read a lot, you instinctively expect, you know, this is the, this is where a short story should stop. This is where it becomes, you know, a novella. This is where it's a novel. But it, you know, it does actually go on. Like, I think I remember the first time I was reading it, I was like, hang on a minute. It's like, I was just looking at how much is left in the book and knowing that there were all these other stories in there as well. Yeah, you do feel slightly on the back foot, I think. It's like, oh!

[00:41:36] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, absolutely. yeah. I remember flicking through and thinking, wait, is it? I thought it was different stories. So maybe it's just, maybe it's just this, this one, but it's such an experience reading that book, and it also feels, I think what's so wonderful about writing is she knew exactly what she was doing, but there, there's also a kind of a great freedom to it. You know, you talk about kind of the time and that, you know, that sense that with some of the stories you can't quite sort of say, you know, where are we at that point? Which, I don't know, for some reason it kind of makes me think of, you know, it reminds me that sort of fiction and kind of storytelling is, you know, whatever you want it to be.

There's kind of these idea of rules, but there's something about sort of Angela de Carter's work that it makes its own rules and it works perfectly within that, and for you as like, as a writer, is that inspiring? is that how you sort of approach your own work? or do you go down a different avenue?

[00:42:35] Kate Mascarenhas: So I actually, I do find it inspiring, and I also, in some ways, find it reassuring. In addition to it's sort of like, laying down gauntlets as well. I mean, it's quite a combination of things, I suppose. I guess, when I'm writing my own stuff, because I don't plan. My first draft is, I, you know, I start off with, like, an image, and with Hokey Pokey, I had, for years, I had, like, this, like, this single image of people cooking in a kitchen, you know, and it being, you know, a kitchen, you know, I wasn't sure whether it was the 1920s, but it was, I knew it was in the past and then, preparing this meat, and one of the pieces of meat has a tattoo on it. Right? And I'd got, I'd got this image in my head for a long time and wasn't quite sure what the story around it was and I didn't, you know, what I tend to do usually is I'll spend sort of four to six weeks where I'll write a couple of pages every day with absolutely no sense of where the story's going.

It's almost like automatic writing, and then I stop when I have something that's pretty much, it's normally, you know, 55 to 60, 000 words, and then I look at it and I think, well, this is a big old mess, because it's just, you know, like, sort of almost bordering on stream of consciousness, but I look at it, and the thing is, we're, you know, as humans, we are drawn to sort of, even when we're very deliberately trying to write nonsense, we're made to create stories, so there is always a narrative thread in there.

So it's like when I get to that stage and I look at it and I think what is the story in this and I see it and I can pick it out and that's the, you know, the process of successive redrafting is bringing out that strand. But, you know, me working in that way, which is quite sort of reflexive, I, it does mean that actually I do end up producing things that are not very easy to fit into a particular category and I think reading writers who don't sort of, or who make their own rules is kind of, is bolstering in the sense that I think, oh, okay, this is... This is kind of what I'm meant to be doing. That's, you know, that's, you know, I might be in my own lane, but that's alright. that's how it should be. Yeah.

[00:44:39] Jack Wrighton: Yes, because I think particularly in the world of publishing, which I think is fair to say, you know, it does like its categories, you know, it will publish things outside of that, just for the ease of, you know, kind of going from kind of a publisher down to kind of bookshop to kind of consumer, you know, there's these kind of useful categories that they'll say, oh, this book's like this and this book, you know, does that. But of course, for writers, that must be, you know, very difficult, and I know some do work, you know, I've spoken to some writers who sort of knew, you know, who say, Oh, when I was writing this book, I knew I wanted to write this type of book, and it has a very clear sort of, you know, you can imagine the kind of marketers going great. We know exactly what to do with this. But of course, you know, this is a creative pursuit. So it can go in, you know, infinite number of directions. So yes, it must be both a kind of a challenge, but you know, nice for you to kind of go, well, I'm not the only one doing that. There's a history and there's a peers that are doing that as well.

[00:45:40] Kate Mascarenhas: And I, you know, it seems to me some, it's like I understand the need for the categorisation, and I do know writers who actually find it creatively useful. You know, and you do need to know some extent of it, well, particularly like, for me, it would be during revision rather than the early stages of writing it, but knowing what people's expectations of a genre are, you kind of have to have a sense of that because you can't sort of subvert Something without knowing how it's typically going to land.

So all of that I think of as important, but at the same time I think I am quite awkward and where I kind of am most comfortable creatively is, you know, in, in the places where things cross over rather than, you know, in, you know, firmly in the middle of a particular genre, yeah.

[00:46:24] Jack Wrighton: And when you were, you know, you were saying you sort of had this initial, yeah, which I love you talking about that initial image you had and with, you know, without sort of, yeah, giving too much away, that's interesting and what that kind of relates to in the story. When did you, so you, you wrote this kind of, you know, as you say, a sort of kind of stream of consciousness, getting the words out and when you sort of step back and look at kind of the whole thing, how much of the story as it exists now was, you know, was there? Was there a lot, I presume, was there a lot that was taken out and then things that were added in like later on?

[00:47:00] Kate Mascarenhas: So, generally speaking, and I'm not, I'm, this isn't typical for writers, I think most writers write long and cut, but because my early drafts are so short, usually what I'm doing is fleshing things out, and I have to, like, sometimes like when I'm kind of in the middle of sort of editing and my husband will come home and he'll be like, you know, how much did you add today? And I'll be like, oh, actually I cut like 500 words. He'll be like, no, Kate, you're getting, you're going backwards. You're getting this wrong.

[00:47:30] Jack Wrighton: We need more!

[00:47:31] Kate Mascarenhas: Not supposed to be like, come on, you know. And I'm like, oh, yeah, sorry. so, so, so yeah, so normally the sort of, the thing for me is actually trying to, trying to sort of flesh out the detail, and sort of build on what I've done and, I mean, so, so what's there in the final draft? I think all of those elements. I think possibly there's a very central section that was a later edition, but pretty much all of the rest of it was there early on. It's just now more detailed. So yeah, the there's kind of, there's a, it sort of moves around a little bit. It goes from, you know, this luxurious hotel in Birmingham that's sort of cut off by a snowstorm. You know, there are some chapters set in Edwardian Warwickshire, you know, that relate to the main character's childhood, and there's also some chapters set in Zurich, where she trains as a doctor, which is just, you know, that was a really interesting city to be researching, actually.

You know, I'm just looking a lot at, sort of, because it's where young... worked, and I'd known that there were female psychoanalysts training at that time, but,it was just really interesting looking at, sort of, what their role was in with, within the wider psychoanalytic, sort of, circles, really, and so all of that was, it was great fun.

Do you ever, when you're sort of doing the research for one book, I don't know, do sort of three other books come to mind as well? I don't know, I can imagine when you're researching something that kind of interests you, there's a temptation to either go down a route which actually for the book that you're writing currently wouldn't work, or do you find yourself quite like, you know what you're there to kind of discover? So, with this one, actually, a lot of the stuff, it's not like there was like an easy monograph that I could just take off the shelf and, you know, it would tell me sort of, you know, how a hotel was run or, you know, or how a, psychiatric hospital was run, you know. there were things that were kind of relevant and I had to piece it together, but also a lot of the time I was looking for primary sources, really, ephemera, you know, things that I could kind of piece together, first person accounts, things like diaries, you know, letters,and sort of putting that all together, and in the end I did have more information than I could use. I don't think that's unusual, and you also have like these weird periods where you... You know, you might spend several days trying to establish, like, one minor historical detail.

The one that sticks in my head is, like, trying to find out whether you could place a telephone call from Birmingham to Zurich, you know, at a public telephone box. In fact, you could, but, you know, it would have been slightly different than it would have been today, and it was actually quite hard to sort of find out, you know, what that process would have been. I mean, I'm sure the thing is somebody else might have found the answer immediately. It's just the vagaries of sort of, you know, finding exactly the right person to ask or just hitting on the right thing at the right time, and there is a lot of chance in that. Yeah.

[00:50:26] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, it must be difficult because I thought that with, the setting of the hotel, there's like references to the kitchens and the kind of the mechanics of it, you know, it's kind of like a great machine with, you know, all these elements, you know, working, and of course, you know, we have hotels today, but there were just a few things which struck me as differences, and I thought oh, yeah I suppose you know there's just of course the structure that we have now wouldn't have been the kind of the structure that they had then and those little things when you're reading are just kind of you know, they're part of the general kind of you know scenery in such a kind of important way they really sort of take you there. But I imagine you know a single sentence can actually be two days worth of kind of rifling through all this stuff to go what was the structure of a kitchen in those days or something?

[00:51:09] Kate Mascarenhas: And there are always gaps because you're dealing with the historical record. So that's just the nature of the work and, but there were lovely things that sort of you find out by accident, you know, I was looking at sort of real life, I fictionalized the hotel in Hokey Pokey, but I was looking at real life hotels that had been there in the 1920s, a couple of which are still standing and when you look at like sort of the records of who was living there, there was, you know, there was a list from the 30s of, you know, all the names and the ages and the occupations of the people who worked at this one particular hotel, and you could tell, you know, from the, that it was a family run business and I don't know, there was actually, there was something that felt very moving about looking at that, and I mean, I didn't use any. sort of real people because I kind of, I think when you're writing about monsters, it's like, and I don't think I'm giving away any spoilers here, there's, you know, there, there are some, you know, there are some pretty sort of gruesome monsters in this story and sort of vampire adjacent type things going on. I just felt a bit queasy about using people who were real. it would, it felt much more sort of straightforward ethically to make my characters pretty much out of whole cloth.

[00:52:16] Jack Wrighton: Yeah, so, yeah, so many things to balance there, and I'm aware, obviously, you know, I sort of did a, you know, a very brief kind of mention at the beginning. I'm aware sort of throughout the conversation, we've kind of hinted at the story of Hokey Pokey, but for our listeners out there, if you could just give a kind of brief description of, yeah, of Hokey Pokey.

[00:52:33] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah. So there is, the main character is a psychoanalyst called Nora who works in Zurich, but she's English and she returns to England to follow this very famous opera singer. And, you know, the nominally she's been paid to spy on her to find out if she's having an affair. You know, her husband wants to know. But, like, there's some kind of personal investment that Nora seems, usually fixated on this woman. There's something a bit odd about her feelings towards her, and while they're there, the snowstorm isolates the hotel, guests start going missing, and some supernatural things start occurring, which suggests that the disappearances have a link to this murder that happened while Nora was still a child and, yeah, so that's where sort of all the mystery elements flow from, and where sort of the horror flows from as well. But, you know, it was just... It was really nice to set up a situation where they're making, they're availing themselves of these services where they're waited on hand and foot in this very luxurious hotel, but it's also a very claustrophobic setting and, you know, and lots of opportunities for uncanniness for, you know, hotels are such uncanny places.

I love them, but they are weird, you know, you're in this place that's sort of... It's kind of pretending to be a home from home, but there are all these constant reminders that it's not. and realistically, all sorts of people can just let themselves into your room. You know, I mean, that's, you know, that's always struck me as an idea that has potential for a horror story.

[00:54:08] Jack Wrighton: Yes, and I think, unfortunately, we've sort of come towards the end of our conversation. I always like to end with a reading from the author, reading from their book. So would you mind reading a segment from Hokey Pokey for us?

[00:54:21] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, no, that's fine. I've got a section that's from the very middle of the book,

[00:54:27] Jack Wrighton: Oh, perfect. That's amazing!

[00:54:28] Kate Mascarenhas: Yeah, and it takes place just outside the hotel with a woman who lives locally. Enid woke to the sound of lapping water. The sun was yet to rise, but she knew, as she tentatively sat up in bed, that the lino would be submerged.

She tested the floor with one stockinged foot, and the threadbare wall was instantly sodden. The boarding house stood at the bottom of the hill, and Enid's room was on the ground floor. Before the morning was out, the flooding would surely get worse. She didn't want to wait till she was marooned in her bed.

Her boots were just in reach by the kitchen door. They'd have to go on first. With her feet more protected, the boots didn't form a fail safe seal, but they do, she set about dressing the rest of her person. The emptiness of her stomach and the stiffness in her joints made her slow. She kept in mind the cathedral as a shelter. It would be dry there.

Outside, the world was turning to water. She drew her scarf around her face. With one hand on the railings, she inched up the slickening path until the cathedral was visible on the brow. Small islands of snow remained. Those that have been the hardest packed, and over the white streak of wand, she saw the unmistakable dark silhouette of Malcolm's dog.

He stood at the narrow entrance to Needless Alley. Enid stopped short, breathing heavily, and let her head fall when the dog turned in her direction. She didn't want him to know he was seen, unsettling enough to be watched by the dead, never mind meeting eye to eye. Odd that he should come back lately.

There had been several sightings after an absence of years. Something had disturbed his rest. She dared look up again when she heard him moving, his paws wet upon the cobbles. He was walking towards the cathedral now. She saw him weave through the gravestones, his tongue unfolding readily from his jaw. At the doors he butted his large head against the wood until it opened and widened enough to admit him.

Enid didn't want to share the church with him. Normally he vanished of his own accord quite quickly. She'd wait a few minutes before checking. For now her eyes wandered back to the darkness of Needless Alley. Not one of the dog's usual haunts. She resumed shuffling through the slush to the spot where she'd first caught sight of him, all feeling in her toes was lost.

She squinted down into Needless Alley. No living creature was visible, man nor beast. A single fresh footprint was still clear in the mire though, too dainty for a man. Enid guessed a woman or a growing child. She rubbed her eyes and let them adjust to the poor light ahead of her. Then she saw, perhaps three yards away, clawed fingers. Palm up and disembodied on the ground, and behind that, a battered head. Enid stepped back. Her first thought was, here's a bad penny. She knew who that head belonged to. The snooty stranger from the hotel who'd given Enid's coat a nasty look. She was a wrongun. She'd been loitering by the crypt door. It was always locked, but she wanted to poke around the other side, that much was clear.

Everything about her said trouble. For her and whoever was unlucky enough to cross her. True in life, true in death, Enid felt, looking at what was left of her. She shouldn't be lying in bits down Needless Alley. The rain wearied Enid. She made for the cathedral. From the narthex, she tried to see the dog. She gasped. He was up on the altar, looking down on his reflection in a silver plate. He pushed his four legs into it, as if it were a pool. His head, body, hind legs, tail followed, and he was gone. Enid walked to the vote of candles. She took a fresh one from the box. It took a minute to find the box of matches. It had fallen to the quarry floor. The first match wouldn't light. The rain on her hands had left it too damp to catch. But the next one burned well enough that she held it to the wick. The little flame on the candle jumped and shivered. A fire that small couldn't warm you. She crept to the pew, genuflected as well as her knee would let her, and sat down to pray. Soon she'd have to walk to the police station. If anyone had seen her leave Needless Alley, they'd wonder why she didn't report it. As soon as she'd said her prayers, she'd go. As soon as she stopped feeling so cold.

[00:59:05] Jack Wrighton: Kate, thank you so much for that wonderful reading from Hokey Pokey, which is out now. It's available at Mostly Books in our shop, or online, or available from wherever you decide to get your books from. Kate, thank you so much for joining us on Mostly Books Meets.

[00:59:20] Kate Mascarenhas: Thanks for inviting me, it's been lovely.

[00:59:24] Jack Wrighton: Mostly Books Meets is presented and produced by the bookselling team at Mostly Books, an award winning bookshop located in Abingdon, Oxfordshire. All of the titles mentioned in this episode are available through our shop or your preferred local independent. If you enjoyed this episode, be sure to check out our previous guests, which include some of the most exciting voices in the world of books. Thanks for listening and happy reading.