- Introduction to the topic of U.S. funding for 'digital twin' chips research and its comparison to other large expenditures.

- Overview of the CHIPS Act, its budget, and its place in the broader U.S. budget context.

- Discussion on the price and subscription models of various EDA tools, from entry-level to high-end industry standards.

- Analysis of the impact of EDA tool pricing on small businesses versus large corporations.

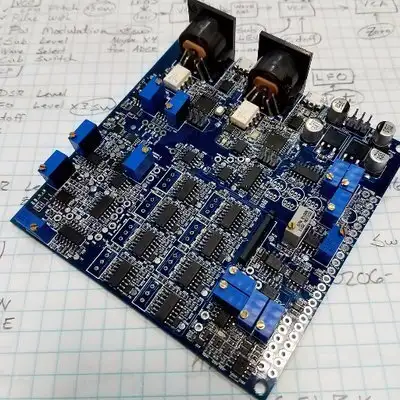

- Parker's personal project update: success with his first KiCad PCB.

- The hosts reflect on the social dynamics of Twitter and its impact on public discourse and political polarization.

- Discussion about the complexities of U.S. political funding and its transparency.

- Comparison of software subscription models and their financial implications for users.

- Reflections on the interaction between engineering, politics, and social media.

- Prevent Prototype Delays: Your Essential PCBA Pre-Order Checklist

- US plans $285 million in funding for ‘digital twin’ chips research

- What are your thoughts on the use of 'digital twin' technology in chip manufacturing?

- How do you think the costs associated with EDA tools affect startups and small businesses?

- Do you have any personal experiences with the challenges of using subscription-based vs. perpetual license software?

Creators and Guests

What is Circuit Break - A MacroFab Podcast?

Dive into the electrifying world of electrical engineering with Circuit Break, a MacroFab podcast hosted by Parker Dillmann and Stephen Kraig. This dynamic duo, armed with practical experience and a palpable passion for tech, explores the latest innovations, industry news, and practical challenges in the field. From DIY project hurdles to deep dives with industry experts, Parker and Stephen's real-world insights provide an engaging learning experience that bridges theory and practice for engineers at any stage of their career.

Whether you're a student eager to grasp what the job market seeks, or an engineer keen to stay ahead in the fast-paced tech world, Circuit Break is your go-to. The hosts, alongside a vibrant community of engineers, makers, and leaders, dissect product evolutions, demystify the journey of tech from lab to market, and reverse engineer the processes behind groundbreaking advancements. Their candid discussions not only enlighten but also inspire listeners to explore the limitless possibilities within electrical engineering.

Presented by MacroFab, a leader in electronics manufacturing services, Circuit Break connects listeners directly to the forefront of PCB design, assembly, and innovation. MacroFab's platform exemplifies the seamless integration of design and manufacturing, catering to a broad audience from hobbyists to professionals.

About the hosts: Parker, an expert in Embedded System Design and DSP, and Stephen, an aficionado of audio electronics and brewing tech, bring a wealth of knowledge and a unique perspective to the show. Their backgrounds in engineering and hands-on projects make each episode a blend of expertise, enthusiasm, and practical advice.

Join the conversation and community at our online engineering forum, where we delve deeper into each episode's content, gather your feedback, and explore the topics you're curious about. Subscribe to Circuit Break on your favorite podcast platform and become part of our journey through the fascinating world of electrical engineering.

Welcome to circuit break, a podcast from MacroFab, a weekly show about all things engineering, DIY projects, manufacturing, industry news, and EDA tool pricing. We're your hosts, electrical engineers, Parker Dillmann.

Stephen Kraig:And Stephen Kraig.

Parker Dillmann:This is episode 430. And so we got a new blog post that I helped write. It's prevent prototype delays, your essential PCBA preorder checklist. And this is just a list. I I would assume most of the engineers that are listening to our podcast know a lot of these tips and tricks, but this is for, like, new people to the industry and new people to PCBA design.

Parker Dillmann:So give it a listen, or a I guess I haven't listened a, read through. It goes through, like, verifying parts of component selection, layout verification, that kind of stuff. Everything that you

Stephen Kraig:It's like a it's a primer on how to do it all. Exactly. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:So, yeah, give it a a read. It's on maccraft.com/blog. We'll put a link in the show notes. So, and before we get into the EDA tool pricing topic, we have some industry news. The, part of the CHIPS Act, that's the what was it?

Parker Dillmann:$280,000,000,000 that we're gonna spend over, I think, 5 years here in the US on chip industry. 285,000,000 of that is going to what's called digital twin chips research, which I thought was I've never heard of that term before. Have you ever heard of digital twin?

Stephen Kraig:I I have not. What does that what does that even mean?

Parker Dillmann:I from glancing through the article, it's about simulation of semiconductors. And they just call Oh, okay. The marketing term is called digital twin.

Stephen Kraig:The wanky term to just indicate that you're you're simulating the thing before you make it.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Before you make it. And so they're putting a lot of money into the, not just manufacturing the chips, but the whole ecosystem around it. Because you need tools and design software to build chips, so they're investing into that that side of it as well.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, that's cool. Yeah. I was that I don't recall that being part of the original. I wonder if that got earmarked on or or tacked onto it. It's, oh, well, we also have to simulate these things.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. The Or or or maybe they're just allocating money that is already part of the pot to do this.

Parker Dillmann:Well, it's called, like, the Chips and Science Act is what it's called now.

Stephen Kraig:Oh.

Parker Dillmann:So they had to add in science.

Stephen Kraig:Wait. Wait. Wait. Did they retroactively go and change the name?

Parker Dillmann:I think so.

Stephen Kraig:Because I thought it was just always called straight up the Chips Act.

Parker Dillmann:Me too. But this is a I have a URL here from white house dot gov. That's the fact sheet on the CHIPS and Science Act. So what's interesting though was I saw some comments on this article about the costs. It's $285,000,000, which is that's that's a lot of money.

Parker Dillmann:Right? Yeah. I'm never ever gonna see that much money. You're never gonna see that much money. Probably everyone combined that listens to this podcast, total combined is not ever going to see that much money total.

Stephen Kraig:I can't even count to that number.

Parker Dillmann:We'll start counting now. See what you get to by the end of the podcast. And so I just have some interesting things to throw out. This is what this is what people complain about online, specifically, like Twitter and Reddit, of how much stuff costs. So the chips act is 280,000,000,000 over probably 5 ish years.

Parker Dillmann:They don't actually say what the length of the time it's gonna be, but they're spending it at about 56,000,000,000 a year, so 5 ish years. One of the big ones that's more recently in news is Boeing's Starliner, the the capsule that's supposed to go to the moon. Right? And it's supposed to take astronauts to the International Space Station and that kind of stuff. They were and this is a fresh moment because I read an article about, like, why the Starliner is it basically failed at Boeing because it's a how it works is a complete it's a fixed price instead of a, what would they call that?

Parker Dillmann:Where they can just build a government for whatever it costs? There's a specific term for that.

Stephen Kraig:There's a term for that? I don't I don't know. Yeah. I'm not sure I'm aware of that term. I don't think the government typically doesn't just let you spend any amount of money.

Parker Dillmann:Boeing can.

Stephen Kraig:When you're the size of Boeing, they're just, like, whatever. Just send us the bill.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. What is that called? I have to find the article I was reading about about it. But, like, when they do development, like, they give an estimate, and if it runs over, they just charge the government, and the government just pays it. But this was supposed to be a fixed price, so they were given 4,200,000,000 to develop this and produce the the capsule, basically.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Is it FFP firm thick firm fixed price?

Parker Dillmann:Yes. Yeah. And but that's only 0.4000000000 a year. So apparently, Boeing lost money is the big thing over on this. They're like a 1,000,000,000 over, and they have to eat at this time.

Parker Dillmann:Whereas if they were developed if they were, like, Lockheed and they had the other kind of normal defense contract where with the f 35, which is also the really famous, highly overrun budgeted government program. They spent 400,000,000,000 since 95, but that's that only only in quotes comes out to 13,300,000,000 a year, which in the grand scheme

Stephen Kraig:That's a ton of money.

Parker Dillmann:It's a ton of money, but we've given Ukraine 37,000,000,000 a year. I think we're at 74 point something billion now to Ukraine. So when you start complaining about the f 35 or Starliner or Really the one that really stands out is the Chips Act, which is $56,000,000,000 a year, which is swamps. The other ones combined is under that total. So, yeah, that's it's it's start adding up what other stuff costs and seeing I guess I guess the argument is if you were against all this stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Well well okay. But you can be you can be for the results, but against the execution. If some of the opposition to the Chips Act was just the idea that it effectively works as a blank check where, you know, it it was less itemized unless We weren't voting necessarily on specifics of what the bill was doing. It was just this omnibus. Here's a ton of money.

Stephen Kraig:Go do some stuff. And I know I'm I'm greatly

Parker Dillmann:No. No. You're right. Simplifies. They allocated but that would Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:They allocated a whole bunch of money, and then they had a committee that would would spend it over the time.

Stephen Kraig:Correct. Correct. Correct. And and and that's where the blank check idea came in where it's just, okay. We have Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:This huge amount of money. How do we actually ensure that it gets spent on the correct thing? So like I said, the opposition, I don't think I I I doubt there's few people or I I doubt there's many people out there that that would be against bringing these kinds of jobs to America or this kind of technology to America. It's just the the execution is almost always where people disagree about it.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, I 100% agree. It's kind of it's it's when you look at it, it's like how would you even structure say you wanted to make it a spreadsheet. So the bill was a spreadsheet that you had to pass for the for the

Stephen Kraig:It just says it has one cell just has 280,000,000,000 up at the top. And then all the cells beneath us, how do we spend this?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So that that's the how do we spend this? Like, how would you even go like, how much would you have to pay to actually because you'd have to basically pay the committee to figure this out of, like, how to itemize it and how much money it would actually take. Because I bet you we are going to end up spending more than the 280,000,000,000 to bring all this all this kind of manufacturing back.

Stephen Kraig:Well, actually, I'm I'm I'm curious, though. The the okay. The the end result of the CHIPS Act is not the same as let's build the Hoover Dam or let's go do this other big program where there's a clearly defined we're done once the dam is functional. Right? With the CHIPS Act, we're subsidizing and and giving money to to these these facilities effectively to get online.

Stephen Kraig:But did we cook in all of the end cases where okay. The Chips Act is complete when what happens. Right. I don't I don't know. And that's that's, again, that's more of the blank check mentality where it's just, oh, we we give money, but what's the end result?

Stephen Kraig:What is the completion criteria, in other words?

Parker Dillmann:When the spreadsheet hits 0.

Stephen Kraig:But but but that's the whole but but but you said, you know, you you expect maybe we'll overrun, but, like, how can you overrun if there's no end case? Like, you just have an amount of money, and then you spend it. And if they're done, they're done. And if they're not, they're not. Right?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I don't know exactly how something like this pans out because this is just I I I would expect that if you were a recipient of this money, you would have to somehow prove that you've spent the money and accomplish what you're going for, but that's not necessarily something that we're privy to.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I'm looking to see what that kind of contract because fixed price contract is what Boeing lost all that money on Starliner. Oh, cost plus contracts. That's what that's what they are Boeing is used to or in, like, Lockheed and all those other ginormous corporations that just get to have lots of money.

Stephen Kraig:I I don't know. That's one of the hardest things I've I've done in my career is work on contracts, which I haven't done a ton of. But just figuring out there's a dance that business guys do. This this this dance where they're where they're they're they're crafting language in these contracts to win things without lying and without falsifying information. And and that's always been really difficult for me because I I tend to be a very honest person.

Stephen Kraig:And so whenever I've worked in these kinds of situations with with contracts, I've I've had people, like, take some of my work and be like, I need to rewrite half of this because you're just telling too much in in this. I'm like, but I'm telling the truth, and they're like, yeah. But that won't win us the contract. So I don't know. Like, I there there's something a little bit kinda like it's it's like on the edge of slimy and gross that I don't want to be a part of.

Stephen Kraig:Some people are just fantastic at that, though. They love that chase, and they love figuring out how to how to make that happen. I'm just when someone comes up to me, they'd be like, how long will this project take? I'll, you know, I'll be honest and be like, oh, that sounds like a year and a half, and they're like, can you do it in 6 months? And I'm like, no.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. Well, we'll tell you we'll tell the customer we'll do it in 6 months then. They're like, I don't know.

Parker Dillmann:So the Hoover Dam for adjusted for inflation was 760,000,000. So quite a bit of money, actually.

Stephen Kraig:760,000,000? Yes. But that pales in comparison to 280,000,000,000. That's true. It's 12 180th.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Right. I think I don't know. Who owns the Hoover Dam?

Parker Dillmann:I'm hoping someone named Hoover. It's a joke. Bureau of Reclamation. A US department.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. See, that that that feels more like the classic idea of the government investing in itself in a way. It's like, people need jobs, throw a bunch of money. Like, the the like, the the classic idea of dig a hole and then pay someone to fill it in even though the end result was we got a, we got something out of the the act or out of the the investment. Whereas the CHIPS Act is taxpayer money funneled to corporations to bring jobs here.

Parker Dillmann:Mhmm. Yeah. That's I don't wanna go too much into it, I guess, but if if you listen to our talk with oh, what was his name? It was about CCBAA Act.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Right. Right. Right. Which that's trying to get tacked onto the CHIPS Act as well.

Parker Dillmann:I think it got passed. Did it?

Stephen Kraig:Did it? Well, when we

Parker Dillmann:were talking, it had not. I'm checking right now. That was with David. That was episode 388. When was that?

Parker Dillmann:Summer last year. I mentioned, basically so if everyone probably knows I'm a libertarian and taxation is a big thing I always talk about with with with regards with the government. But on that podcast, I basically said, if if we're spending money on, you know, tax money going to people and infrastructure and stuff that everyone here in America uses, I'm generally okay with that because I see that that's actually something useful. Public education. That because in Texas, we pay a lot in property taxes, because we don't have a state income tax, and those property taxes go directly to the schools.

Parker Dillmann:That's what that money is for. So I'm okay with that. That's public I went through the public education system. It's just me giving back for the next generation. Right?

Parker Dillmann:But it's when when a big old blank check gets signed or money goes overseas to some, you know, war effort or something like that. It's it's really hard for me to justify being excited about my tax advice money going there.

Stephen Kraig:Well and and and the thing about that is you have to you have to justify what the end result of the money is. It can't just be a blank check. There has to be it's not like I'm not trying to make it sound transactional, but there has to be a reason for you giving that that money to someone else. And aid is one of those, but, typically, it extends far beyond aid. So, obviously, you you're referencing the, the situation in Ukraine.

Stephen Kraig:And and what? You said we had already spent $74,000,000,000 in 2 years on that on that effort. You know, what are the results of that? What what is I'm not I don't wanna make it sound like what does America get out of that. But yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Sure. What are the results of us spending that much money? Is it is it purely to prevent a particular outcome, or is there more to it? And the answer, I think, is always there's way more to it than that. So I don't know.

Stephen Kraig:That that one's actually that one's really polarizing. It's and and and the thing about it is it's polarizing in so many ways that I that that have been that they don't feel like they fit in one particular aisle or the other in terms of politics, because you can find people on both sides that are just extremely you must support or you must not support this particular thing. It feels so much more black and white than a lot of our other sticky situations that we get into.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's especially because a lot of it is down to social media too, making stuff way more polarizing. When you only have how many characters do you get in Twitter? A 120 something?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, I think they upped it a few years back. Oh, yeah? But yeah. It was a 128, but then I think they bumped it up to twice that

Parker Dillmann:or more. 280 characters. Yeah. But it's still not a lot.

Stephen Kraig:No. It's it's it's not. Right? It's yeah. How do you have, like, how do you have actual discussions about this when you're just yelling at someone in 280

Parker Dillmann:characters? Exactly.

Stephen Kraig:To Twitter oh, I'm sorry. X is is it's okay. It's okay to call Twitter here. Okay. It's it's I don't know.

Stephen Kraig:I think I I would not be surprised if, you know, a 100 years down the road, the humanity finds out that Twitter was not good for the human psyche. You know? Or, like, that's not like, I say, it's not like a good way for us to communicate even though it seems like a good way for us to

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. And I I use Twitter as my only social media, and I think it's because it's how easy it is, and I do keep in contact with a lot of other engineers on it. But I found I if I found a couple Discord communities I really like, and I find I use those more than, let's say, Twitter. But, honestly, I've been trying to navigate back to actual old school forms. Circuit break hyphen or was it circuit hyphen break dot maccred.com?form.maccred.com?

Stephen Kraig:Let's just go with forum dot maccred.com. That one's that one's the easiest.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. And trying to because now you can actually have proper discourse with people, and it's so much more nicer.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. It also may be that you're getting older and and that's what you crave. Right? Long form discourse where you're willing to actually spend time as opposed to just putting whatever platitudes up on x or just screaming about whatever you're passionate about about the moment, you know, and then, you know

Parker Dillmann:I think the most angry I've ever gotten,

Stephen Kraig:pot on that one.

Parker Dillmann:That's for sure. I I I definitely refuse to talk about politics a lot. So because I think that's

Stephen Kraig:I think that's actually really healthy on the x. Just just avoid it. It did 100%. What what what kind of good is gonna come from that?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's it's the It was a couple years ago. Learning that you will never change someone's mind on the Internet, especially on social media. You'll never change anyone's mind on the Internet. Completely change change and and and also knowing half the people out there are just AI bots.

Parker Dillmann:Maybe not even AI, there's bots.

Stephen Kraig:Is Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Take that to heart and then everything your blood pressure goes down. Stop worrying about stuff. What people say on social media doesn't matter.

Stephen Kraig:And and and it's funny because you can you can pour your heart and soul into explaining your position in

Parker Dillmann:In 240

Stephen Kraig:characters. In 240 characters, but but even that is like a like a a feat where where you appropriately get your point across and you you give good information. And then the very next post is just a shit poster that just throws something some some garbage there, and it just completely deflates everything you just said.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. The the amount of bad faith actors, I think a lot of

Stephen Kraig:them are bots too. Just shitposting bots?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Well, just bad faith bad faith arguments and that kind of stuff. Yeah. Like, whenever whenever I see someone post something about America bad, it's just America is bad because of this. I'm like, that's a bot.

Parker Dillmann:Blah it. Blah it. Blah that person.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, why would why wouldn't someone even program a bot to do that, though?

Parker Dillmann:There's there's actually funny you say that. There's actually huge a lot of it comes from China bots, and then a lot of them are from Russia. Like, Russia's actual, like, public what is it? Their international I used to know this. They used to they used to publicize their, like, how they maybe it was leaked, but they had something where this is what we do.

Parker Dillmann:Like, our our goal is to just destabilize other countries in this manner by splitting basically society in those nations. I'll I'll have to find it, see if I can find that that article again. But once you realize that's like, why has the United States been so divided over the past, what, 6 years now? 7 years? Makes a lot of sense when you start looking at it as as first way.

Parker Dillmann:If you sit down with someone else that shares a complete opposite view of you, just sit down next to them and talk to them, you do not scream at each other in 240 characters.

Stephen Kraig:No. And 99% of the time when you do that, that person doesn't come off as your mortal enemy. Whereas in in in x, it's this person is planning to kill me, and I have to tell you know, I have to tell them everything about my political stance.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's the oh, man. So this we're getting like a social media rant now, I guess, now. The whole

Stephen Kraig:Why not? We're not? No. I said why not.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, why not? The whole where the Internet is now so if something is wrong or you feel like injustice has happened to you because of a video game is going to require a sign in to another service. This is this is this happened over the weekend.

Stephen Kraig:I was about to say, are you are you referencing Sony here?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So so yeah. People will send death threats to developers, software developers, and to corporations. It's, like, when when did we get at a society where that's okay?

Stephen Kraig:You know where? It's whenever we became anonymous. You're anonymous on the the Internet. You're not really, but you but you feel like you are. If you have to stare another human being in the eyes and say horrible things, I'm going to kill you or whatever those they said to those developers, There's a considerably different impact to looking someone in the eyes versus just typing in 200 something characters.

Stephen Kraig:You know, obviously, you you can't type I'm gonna kill you on on Twitter. But but the anonymity is just empowers people to do horrible things You or say horrible.

Parker Dillmann:You say that, though, but a lot of these people that's it's their account, and they they have their name on their account. So they're it's not truly the anonymous thing either.

Stephen Kraig:I do think, though, I do think that there is a disconnect between looking at your screen and looking at a human being.

Parker Dillmann:I a 100% agree.

Stephen Kraig:A 100% agree. The anonymity because the the digital nature of what spans in between you just does it doesn't feel like a human being on the other side.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I think I think it also stems from frustration, and this is on the person who's making, by the way, this is not justifying their behavior. Just trying to understand it. I think it's they're frustrated because they don't have any control over that situation as well. And Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:I like, for me, if I get frustrated, I'll go in the garage and I, like, you run power tools and and work on an engine or whatever. Right? You do the same thing. When you get frustrated, you go down in the garage or in your basement and go work on something.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Or or You

Stephen Kraig:try you try to channel it into something healthy.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Like, go exercise or lift weights or something like that. I I I walk my I walk in extra when I get frustrated.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. I I've got a I got a funny story. So behind my house growing up, I I lived in the in the not it wasn't the suburb. Well, it was the suburb, but it was like the edge of the suburbs. So my back my backyard backed up to a street and then beyond that was just like Woods.

Stephen Kraig:Everything in the other direction was all suburbia. So we were just the edge of suburbia. Across the street, there was a field where people I don't know why, but they would just dump trash there. And and not just, like, small amounts. There was, like, tons of it.

Stephen Kraig:And at one point in time, a few dump trucks came in, and they dumped toilets. And we're not talking about 4 or 5 toilets. 10 toilets. We're talking about probably a 150 toilets into this giant toilet mountain. So it's this huge white porcelain mountain and and, of course, they were all beat up and and and and trash and whatnot.

Stephen Kraig:So I used to when I would get frustrated, I would get my sledgehammer and I would just go to toilet mountain and just go to town on these things And it was so therapeutic to just blast a whole bunch of toilets, and you feel good at the end of that, but I don't know. Maybe I was lucky because I had toilet mountain.

Parker Dillmann:Well, there's also there's you know how they have escape rooms? Yeah. So Oh, yeah. So escape rooms are like a building where you can enter with your a bunch of friends or whatever, and and there's puzzles, and you try to escape. There's a bunch of different it's almost like crypto puzzles at Defcon and stuff like that.

Parker Dillmann:It's kind of cool. Mhmm. But they have kind of the same idea, but it's you just get to break shit. Yeah. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. You just

Stephen Kraig:get to go nuts for a period of time.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. You know what? Next time I'm up in Denver, we should go do an escape room. I've never done one.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, you've never done one? Okay. They're fun. Yeah. Oh, well, actually, wait.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. I shouldn't say that. I've done an escape room once, and I actually had a really bad time at it. But I could tell that it would be really, really fun. And the reason why I had a bad time is because I love artists to death, but I did an escape room with a bunch of artists that I didn't know.

Stephen Kraig:And I was the only engineer there. And I'm trying to think of things analytically and logically to get out of this room, and these artists are just going freaking ham on everything. And I'm like, guys, what you're doing makes no sense. And so you kinda have to have I feel like it would be fun to have a good mix of people, but if you're in an escape room with people who don't think anything like you, then it's frustrating as hell.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. We should go do more fun. That sounds like a lot of fun.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. It'd be really fun.

Parker Dillmann:This podcast is off the rail.

Stephen Kraig:Why not? We're having fun.

Parker Dillmann:So I guess to circle it back around is on on costs, especially US taxes and stuff like that is just take it take look at look at everything from, like, a mile like, start looking at everything. What and so sure. It's a lot of money, and we print a zillion dollars, but is is there anything we can do at this point?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. The one thing I wish we could do, and I just don't think anyone would be willing to do it, is to have more granular things that we vote on. Instead of these gigantic money pit bills that we vote on, these omnibus bills, I wish we could just vote on this money goes to this thing. Vote yes or no. You know?

Stephen Kraig:And and it's not $280,000,000,000. It's, you know, a 150,000,000 to this, you know, to this one bridge or whatever. You know? Vote on single topic items.

Parker Dillmann:Well, that's a lot of cities do it or a lot of cities where you will vote on that kind of stuff.

Stephen Kraig:I think what you're the US Congress.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I think what you're talking about is is because what people say is, oh, United States is a democracy. It's that's actually incorrect. It's a republic because you vote for representatives to vote on the majority of things for you. That's how it works.

Parker Dillmann:That's why we don't we as the voters don't actually vote on an omnibus. We vote for a representative that does vote on that.

Stephen Kraig:That votes in the way that we would if we did.

Parker Dillmann:You would hope. Well, that that

Stephen Kraig:that's that's the plan. Well, and that's the reason that's that's that's the reason why they have term limits because if they don't vote the way you want, you just put someone else in that hopefully What if votes the way

Parker Dillmann:you want. I know we've been shitting on on Twitter. What if what if you voted on omnibuses via Twitter?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, god. Twitter You wanna make Twitter more of a cesspool? No. No. Thank you.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. We do we do not need electronic voting through social media.

Parker Dillmann:I think a lot more people that would vote, though. No. Because then you'd have to have some kind of way of authenticating through Twitter and that sounds awful.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. No. Let's let's not do that. I I I I think okay. I think there does need to be at least some price to vote.

Stephen Kraig:And what I mean by that, voting is a it is an absolute right, and it is something that you we should take pride in, and it is part of our civil duty, but it shouldn't be the absolute easiest thing to do. I think you I I like the idea of you go to a place and this this is my time to vote. And I've done my research, and I've I know the issues, and I know the people I'm going to, and you put effort into it. It shouldn't just be like a push notification that comes up on your phone and be like, which thing do you like? Press yes or no.

Stephen Kraig:Like, I don't think I don't think we need to boil it down to it being that easy. There needs to be some effort behind it.

Parker Dillmann:You made it easier to because the problem we have with that is there's not a lot of good pollings there's not enough polling stations. That's the problem with that. And going to location so the problem with that is, so the the problem with that is there's a the people who work the law is if you go vote, your your employer can't stop you. Right? I don't know if they have to pay you, though.

Parker Dillmann:Mean that No.

Stephen Kraig:I don't think they do, but they have to allow reasonable time for you to go

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. But they don't pay you. And if you're working hourly and the fact that the majority of people in America are working paycheck to paycheck, meaning that they missed a couple hours, they're gonna be behind on their bills. And now you're basically those kind of people just can't get to the voting station at all because they just they they don't have the money because their their social economic position is they can't take the time off to go vote, basically.

Stephen Kraig:Well, but but but the polls are open in many times early on and after work as well, and and there's it's rare that there's there's voting that is only available in one day for a short period of time. So they voting is is typically fairly easy to schedule to

Parker Dillmann:figure out how to do this. You're assuming that if you can go vote, you can get in and out. I know for a fact that's not the case.

Stephen Kraig:Sure. You know, if you don't system it's going to be perfect.

Parker Dillmann:If it was showing up at a station and it was, like, 5 minutes in and out, you can do it on the way to work, or you do it on the way back from work, or on your lunch break. Sure. But the problem is that's not the case.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Well, I mean I mean, you're you're making a bunch of claims here. I I I would be curious to see what the data actually shows on that because, I mean, the way you're presenting it isn't it doesn't work this way. But

Parker Dillmann:I just know from the

Stephen Kraig:last across the board.

Parker Dillmann:I'm talking about this is, like, Texas elections. The the data shows that basically, like, in the less fortunate social economic areas have less polling stations, and they run out of materials. Because we have to have, like, special paper now.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I remember that was actually a really unique thing in Texas last time where they were they were running out of paper. And even when they called for restocking, it was taking a significant amount of time. Yeah. And so Now so that's an example of the system breaking down.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:And so you had really long poll lines and people just not being able to vote. So I think there's a way we need to speed that up and also make it more accessible to people because I'm, honestly, I'm, like, putting effort into it if a part of this way is it doesn't feel like even if you do all your research, you don't get anything back from it.

Stephen Kraig:Other than the satisfaction of of doing your duty. I guess. I I you you I vote. Participated in in one of the greatest governments that has ever existed. It's kind of cool.

Parker Dillmann:Maybe if my politicians actually pay attention to us normal people. So but that doesn't seem to be the case.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:If if they All

Stephen Kraig:I'm saying is I don't think we should boil it down to a push notification on a phone.

Parker Dillmann:I can agree there that that Twitter thing was a joke, but I do think we need to figure out how to make it faster to get in and out. If you wanna use polling stations, we need need a lot more polling. At least here in Texas, a lot more polling stations. Because if you're out in the suburbs, I waited I think the last presidential election, I waited 3 hours in line, early voting. So Wow.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It was ridiculous.

Stephen Kraig:I I I've I've I guess I've been lucky because I've never had that situation. Every time I've ever voted, it's just been walk in, show them my ID, go to town.

Parker Dillmann:Now for all the local elections, it's always like that. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. 1, a

Parker Dillmann:lot less people show up, and they have all the normal polling stations open. And by the way, this is Houston, Texas I'm talking about. I did vote a couple actually, no. I didn't vote at all when I was in college and up in Austin. And I never became a Oklahoma citizen when I worked in Oklahoma.

Parker Dillmann:So I'd those 6 months in Oklahoma, I I didn't partake in any elections up there. So, yeah, I've actually only know about voting in Houston. But, yeah, the presidential elections, there's no good time to go to the polling station at all.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. So You know, up here, they we do we do vote by mail in in Colorado, which I know there's lots of potential. Let's just put it that way. I mean, people we may may upset people with this, but the the there's there's potential for fraud with that. I I I absolutely think that there that could happen.

Stephen Kraig:I'm not saying it does. I think it could, but so far, it's been it's been pleasurable. Let's put it that way. Because we get our ballots, and then a few weeks later, Colorado is really fantastic at sending out this whole packet that explains every single thing you're voting on, and it gives the primary four vote and primary opposition. It gives voices for those that have explanations about them.

Stephen Kraig:Things like, you know, we were just mentioning the Chips Act. It could be a blank check. The opposition will say, we don't want to allow for blah blah blah. We don't wanna give someone a blank check. And and and so

Parker Dillmann:It explains like if there's a proposition, it says this is what the proposition's for. This is what what it's against.

Stephen Kraig:And what's nice is the they they don't seem to do much editing to it. So, you know, whoever's for or against their words seem to be their words, which is which is fantastic. And and and so sometimes the the opposition will write, here's how this person is purposefully misinterpreting or or or or obfuscating the the language in this to make it seem like it's this. Well, it's that. And so I've I've really appreciated that too because I like to sit down, take a night, read through all the propositions, make up my mind about each one.

Stephen Kraig:And so mail in voting has been fantastic for for that. I actually I'm I'm fairly pro that. Although, like I said, I'm skeptical about the the ability for it to not be gained.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I'm I'm I'm a 100% for Malin because it does solve, basically, the problems that I have with polling stations. And I've done some I wouldn't say research, but I have looked for is there problems with fraud for it. And everything I can find is it's specifically not fraud happens more at polls than it does in mail in ballots. That's the only thing I can find.

Stephen Kraig:Yep. I don't know. There's something more if this is purely an emotional statement, but there there's something more trustworthy in my mind about showing up to a place and, you know, pressing the button on what I want. There's just something that feels more solid than that as opposed to just taking my piece of paper and dropping it in a mailbox and being saying trust this. Right?

Stephen Kraig:Mhmm.

Parker Dillmann:I know. I can see that being a a valid concern.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Oh. But like I said, I I don't have any data to actually back any of that up.

Stephen Kraig:But the one thing I I can say, I don't trust anyone to not cheat. So if it was possible, I would absolutely a 100% think that somebody would 100% do it. I I I generally think that if humans can do corrupt things, they generally tend to do corrupt things.

Parker Dillmann:I think that's what we're talk did we ever talk about I think it was last week. Yeah. Because last week, we talked about Apple. And and

Stephen Kraig:I like how we went from corruption to Apple.

Parker Dillmann:Oh, no. No. No. No. No.

Parker Dillmann:Not about that. It it's the whole corporations. Their entire purpose is to be greedy because that's that's they're codified to do that. So it's it's it stems from that. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Mhmm. If so, Man, we are way off topic. It's a weird podcast. Yeah. Let us know I don't even know I want people to respond to this.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, what what even would they respond to? We're all over the place. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:I mean

Stephen Kraig:You you know what? Okay. Typically typically before an episode, we've said this many times, Parker and I typically pregame. And most of the time, that's it's not, like, intentional. It's just we both log on.

Stephen Kraig:We're working on the show notes, or we're doing whatever. We just start BS ing about a bunch of stuff, and it usually ends up being kinda like what we're talking about

Parker Dillmann:right now.

Stephen Kraig:But we didn't pregame a lot before this episode, so I guess we're getting it all out in the opposite.

Parker Dillmann:Basically, what we've been thinking about for the past week.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Right.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's it's interesting stuff. I don't pretend to have I don't pretend that we have solutions for these kind of things. We're electrical engineers. What I like to do the best is I just like to understand what the problems are.

Parker Dillmann:That's what I like to try to get to. Oh. And figuring out that kind of stuff. That's way more interesting than actually finding a solution half the time.

Stephen Kraig:I I I I really enjoy looking at a problem and and knowing that I can come up with what I think the answer to this problem is pretty quickly, but then stepping back and saying, but what do other people think? What are the other arguments that are going to it and trying to understand someone else's argument? Because it's really easy to just sit back and be like, this is how it is. This is my position and I will die on this hill. It is very, very hard to try to understand someone else's position.

Stephen Kraig:Now you can hear someone else's position, but understanding it is the next level. And and it's fascinating to, in some cases, step back and say, how the hell did you even come to that conclusion? What is your what is the pattern or path that your mind had to go to to say this is how I think it is and this is the hill that I'm gonna die on? And I think that really helps either tear down my own position or bolster it even more.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's not something you can't do in 240 characters.

Stephen Kraig:And we're right back to Twitter.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Right back looping back around. Alright. Let's talk about EDA tools now.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Okay. Yeah. We're we're we're nearing the end here.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. But Let us know what you wanna talk about with if you about that kind of topic. It's kinda weird. I won't blame if people are like, politics and taxes. I'm gonna turn this off.

Parker Dillmann:I I will not blame people because we tip we never ever talk about that kind of topic. But it's just something Yeah. It's been coming up a lot in social media and the news, and Chip Sacks has been making a lot big splash recently.

Stephen Kraig:So We're in an election year. Elections are always fun. Yep. So Okay. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Let let's let's pivot. Let's pivot and talk about EDA tools. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:This is what people are here for.

Stephen Kraig:So so I I I had a topic that I wanted to just kinda go over because I don't think we've ever really covered this. I I I I wanna talk real quick about the the the price to play when it comes with EDA tools.

Parker Dillmann:This is gonna be more people are gonna complain about this than Than all the politics. The politics we just talked about.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Actually, I would love that. I would really love that because I went out and I got pricing information on a bunch of different EDA tools. Just, you know, if say you're starting a new business or you're a manager coming in and you need to start an engineering team or whatever, what do you what do you even go and buy? And what, you know, what kind of money do you have to spend?

Stephen Kraig:And what EDA tool do you pick? I thought it would be fun to just kinda take a cross section and look at EDA tools. But before I do that, I I have a question for you, Parker. Mhmm. What are your thoughts on subscription versus ownership when it comes to software?

Parker Dillmann:Oh, boy. So when Eagle moved to the subscription service, I was actually okay with it because so before then, Eagle and a lot of people didn't like that. And I understand why because you would pay a big lump sum, and then you got to keep the software forever forever forever. That's what a lot of people did. A lot of people would buy, like, version 6 of Eagle, and they would be using version 6 forever, basically, because they have a perpetual license, which is totally valid.

Parker Dillmann:I don't understand why I'd do that, but I like getting the new updates. And so the lump sum was paying the lump sum basically every year for the latest version Eagle was way more expensive than the than the subscription service was. It still is, by the way. I think Eagles 6.80 a year, and then back when Eagle was a perpetual license, I think it was, like, 1,500 for that perpetual. So, sure, if you were keeping the same version of Eagle for 3 years, it would work out, but I always wanted the latest version.

Parker Dillmann:So it really depends because I I know a lot more software are moving to subscription. And what we said earlier is, corporations are greedy because so they're doing money. Right? Money. 100%.

Parker Dillmann:What what the subscription service really does is it it flattens out their their prediction of money, basically, their income. Whereas, you know, if if you're selling to say Eagle and you're selling the new version, you have these big spikes when you have a new version come out, and then it just trails off. Right? So it's very hard to gauge your runway of a company when that's your model. Whereas subscription service, you can be like, okay.

Parker Dillmann:We have 10,000 subscribers that are paying this is like Netflix. Netflix is probably as 1,000,000 probably or more. But, yo, we have 10,000 at $10 a month. So we have that's our income basically for our service. So I guess I'm kinda indifferent on this because it really depends on what is offered.

Parker Dillmann:If it's a software that never changes, I am I'm much against the subscription. But if it's a software that changes a lot and is in actively development, I can see subscription working out. This kinda carries over to video games where you have, like, live service games, like World of Warcraft, and I think there's Fortnite, etcetera. I don't play Fortnite, but the only one that I play really played is well, the workout then back then you didn't even call that a live service game. But it's a subscription service game.

Parker Dillmann:So you pay x dollars a month, and then you get all the updates and the new stuff. Right? Whereas the traditional model was you pay $60 and you did a video game. Right?

Stephen Kraig:Right.

Parker Dillmann:And you get that video game forever.

Stephen Kraig:Which, surprisingly, that $60 has been $60 for a long time.

Parker Dillmann:Very, very, very long time. It's up it's up to 70 now. Most triple a games are

Stephen Kraig:But it but it was but it was a it it is 70 is more of the norm now with video games, but 70 was not unheard of before.

Parker Dillmann:No. If you want history, the n 64 had $70 games.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yes. Absolutely. I I I paid $70 for a, a Super Nintendo game back in the day.

Parker Dillmann:Boy, it had the FX chip in it.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Right. Right. Right. So so okay.

Stephen Kraig:Here's my thoughts on when it comes to subscription. If if if I'm paying a subscription service for software that I'm just getting the software for that subscription service. I typically don't really look favorably up upon that. And and and and I understand that's a little cryptic, but let me explain it. I subscribe to Fusion 360, and I think that is worth every penny of that subscription service.

Stephen Kraig:And the reason why is because I couldn't afford an equivalent of that That is not a subscription service. The amount of stuff you get with with with Fusion 360, You get Eagle. You get all of Fusion 360. You get all of

Parker Dillmann:Like,

Stephen Kraig:the cam tool. Plugins, all the analysis, all the camps of that if I wanted to purchase that as a stand alone software program, that would be tens of 1,000 of dollars worth of stuff. In my opinion, that's worth the subscription service. But if if I say have 2 pieces of software that do the exact same thing and one is a pay it, you get it perpetual license and one is a subscription service, but they do identical things, I'll I'll I'll lean towards the pay once for it thing. So the subscription service, I feel like I need to get more.

Stephen Kraig:I need to be able to by subscribing to it, I get more than what I could afford if I wanted to pay for the the the standalone. That that is a justification in my mind at least for, paying for a subscription service.

Parker Dillmann:It's kinda like the difference between you're paying how much does Netflix cost down? $17 a month? I canceled a long time ago. It was it was 999 when I canceled it. But for, let's say, $17

Stephen Kraig:and you're and let's this is using your analogy.

Parker Dillmann:For $17, you have access to a 1000000 movies. How much would it cost to buy all a 1000000 of those movies?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah. Well, that's an extreme example. Yeah. That's right.

Stephen Kraig:Right. It's it's your logic. Sure. Sure. I guess what I'm saying is the alternative to Fusion 360 is I would have to buy an EDA tool.

Stephen Kraig:I would have to buy a cam tool. I'd have to buy a 3 d modeling tool and blah blah blah. If I were to price all of those things out that would have the same levels of features as Fusion 360, there's no way on earth I could afford it, and I wouldn't be able to do it. Well, like, what

Parker Dillmann:if we're talking does SOLIDWORKS have a subscription?

Stephen Kraig:A stand alone?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Probably.

Parker Dillmann:Pricing guide.

Stephen Kraig:I feel like the value just needs to be lopsided in in my favor. And with the Fusion 360, it does feel that way. They have to have a subscription. They

Parker Dillmann:do have a subscription. But the stand alone for for standard, I don't know what the different levels mean. The standard premium professional as of 2 years ago, 4, 8, and 12 k.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Like, 4 k, and that's just SOLIDWORKS, which is 3 d modeling. Now there's there's a lot more to it than that. But does it come with a thermal analysis?

Stephen Kraig:Does it come with, cam? Does it come with an EDA tool? Does it come with all this other stuff? Probably not. So even that is not a good enough representation of what you get for a subscription, which frankly, $680 a year is expensive.

Stephen Kraig:I'm not saying it's not. I'm just saying I feel like you get way more out of it for that that price.

Parker Dillmann:No. I hear you.

Stephen Kraig:You get you get 15,000, $20,000 worth of software for 600

Parker Dillmann:and 80 a year. Yeah. That's what? That's 4 Netflix subscriptions a month. You're probably you're probably subscribed to more than 4 video streaming services.

Stephen Kraig:Maybe. Maybe.

Parker Dillmann:I just went through and canceled all that stuff. That's not using it.

Stephen Kraig:Well and and and the whole reason I bring that up is because EDA tools, which is what this topic is about, is kind of broken into your subscription or your pay once, cry once plans. And it seems to be that everyone is tipping a little bit more towards subscriptions even though subscription has actually been around for quite a while with EDA tools. In fact, I feel like EDA tools had this going on a long time ago, but they just described it in a different way. You still purchase the package, but they'd have, like, maintenance fees or things like that that you would pay or upkeep charges and stuff that you would pay on a on a on a regular basis. So I feel like they've kind of just rolled that up into, okay, well, now you don't own the software.

Stephen Kraig:You just pay just the maintenance fees.

Parker Dillmann:You paid for the battle pass for your

Stephen Kraig:e Mutual. I like that, the battle pass.

Parker Dillmann:That's what it is. Because you because you can I think you can well, actually, I take that back? I know there's some software if you refuse to pay the maintenance, they just lock your licenses out

Stephen Kraig:now. Correct. Correct.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:And some of them okay. So so some of them also offer short term leases, I guess, you could say. So, like, monthly seats where you could just turn it on when you know you there's a surge and you know your double e team needs 5 licenses. So maybe you buy 2 perpetual licenses, but you need to you need to bump it up because everyone's working on a board, and then it and then it goes down.

Parker Dillmann:Right? Yeah. You go to Blockbuster and rent. Rent.

Stephen Kraig:Rent a seat.

Parker Dillmann:Rent a seat.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. And and and with the subscription stuff, you also get a lot of the extra plug ins, a lot of the extra analysis, which for most of the other tools with that don't have the subscription model, those are additional charges that you get paid for, or they can also be additional subscriptions that you pay for on top of that. You can have a subscription to a plug in that plugs into your subscription that you have for the main tool. So it gets complex really fast, but I thought it would be fun to break EDA tools down into 3 different sections that we can describe their costs. And if you are looking for a new EDA tool or if you're looking to outfit your double e team, hopefully, this gives some firepower to you.

Stephen Kraig:So so the first one, I I called it the real small players, and this is all the free stuff. This is all the stuff that if your company is really small, you're just starting out, or if you have a very, very simplistic product, this is a potential option for you. And we got stuff like free PCB, Libre PCB, EasyEDA, PCB artist, and pad to pad. These these programs are all free. A handful of them do come with some baggage where I say baggage as in it's like a a larger company created it, this software, such that you would use their service to purchase parts or or things of that sort.

Stephen Kraig:So that's something to keep in mind with these. Usually, it's free for a reason, minus perhaps Libre PCB. PCB is what that's open source. Right? Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:So I think free PCB is also one of the it doesn't have the baggage.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Right. Right. And so I'm I'm I when I say that they're the small players, I don't wanna make it seem like they're not feature rich or capable.

Stephen Kraig:It's just they they're gonna have the the least amount of tools, let's just say, in terms of making your life easy. And if you're looking to design the highest technology out there, these are probably not your options. So just keep that in mind. So the next tier, shall we say, is, what I call the small player. So we had the real small players and now we're at the small players.

Stephen Kraig:And some of these straddle the line between not being small anymore. I put KiCad in here, and the reason why KiCad here is here just it's just because its user base is so gigantic. I think it totally fits within this category. We have Eagle at, $680 a year, and that 6.80 is the Fusion 360 cost because Eagle is now wrapped up in there. And then, of course, I threw DIP trace in there just because that was that's my tool, and that is anywhere from $75 to $995, and that's a perpetual license.

Stephen Kraig:The DipTrace. But when you buy into a version with DipTrace, you buy that version. If they upgrade to the next version of DipTrace, you have to pay the price difference to go to whatever the next version is. I have DipTrace 4 right now, and I know they're going to be releasing 5. And if I wanted to upgrade to 5, it's probably gonna cost me $300 to upgrade to 5, but that doesn't mean that 4 loses its viability whatsoever.

Stephen Kraig:So, actually, what's fun is in this category, the smaller player category with DIPtrace, Eagle, and KiCad. KiCad is free, Eagle is subscription, and DipTrace is perpetual license. So there's 3 options there in case one of those works for whatever your pricing plan is. So then the next level up is what I call the big players, and these are all you the, like, professional level. Not saying that the ones beneath us are not professional.

Stephen Kraig:These are just the ones that, like, have the perception of the professional level EDA tools. So, of course, there's Altium. That's about $55100 a year. I actually confirmed that the other day because a buddy of mine just purchased it, and that is a yearly price. I don't think they call it a subscription per se, but it this fits more of the maintenance fee style.

Parker Dillmann:Gotta get that Altium battle pass.

Stephen Kraig:And and and to to be honest, when it comes to to this to what Altium gives you, $55100 a year may be a steal for for what you're looking for. Because Altium is very feature rich, and it has a huge community, and it does have all the all the options. It may not fit your enterprise level, though, because a some of these other tools are more suited for, oh, hey. You have 2,000 engineers working at your company. We have tools that are prepped and ready to go for 2,000 engineers.

Stephen Kraig:Whereas, Altium may be more suited for a team of, oh, you have 10. It might work better for you in that sense. So there's a lot of research to do in terms of which one works best for your size of your team.

Parker Dillmann:I would say a better way to redo your tiers is size of company or size of how many people working on your on these projects.

Stephen Kraig:Well, yeah, I I could I could see that too, but but for example, my buddy who just bought Altium, he's the only engineer at the company. So, you know, what he's the only person at the company, and he's one of 3 people. So size of company doesn't necessarily judge it.

Parker Dillmann:So what what I'm saying is if you're just building boards, you don't need probably I say just building boards because all these programs eventually build boards.

Stephen Kraig:Just build boards. Right? All of these. That's the goal.

Parker Dillmann:Well, I'm getting that is if the complexity of your projects. If your if your complexity is low and you don't have a lot of people, then you can get away with probably something like KiCad, Eagle, DIP trace. Whereas Right. Altium starts putting in tools that allow you to manage stuff across other projects, like your library, a parts. It helps you manage between 2 engineers.

Parker Dillmann:It handles that stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Document control, revision control, history, things of those sort. Just just keep in mind is as you go down the list, those things are not unachievable. It's just they end up being more in your control. In other words, like, when you get to the bottom of this list, it's more well, however, you saved it in in your computer is how you do revision control. Whereas as you go up the list, they they they they tend to have more tools that equip you for things of that sort.

Stephen Kraig:Yep. So so next on the list is is Cadence OrCAD, which this one is interesting. There's there's there's a handful of options with it. Actually, a lot of these have a lot of these larger companies have multiple different offerings that do kind of the same thing, and and so you could choose like, for instance, with with Cadence OrCAD, there's Allegro PCB Designer, which is $1500 a month for a seat, but there's also the OrCAD X Professional, which to be honest, I don't know what the difference is between them other than the fact that Allegro is 1500 and OrCAD Professional is 52100. So you'd have to research what the difference is between them, but you can see that as we go down this list, things are starting to get quite a bit more expensive.

Stephen Kraig:Inside of Siemens, there's pads, which has more affordable options of about $250 a month, but they do go all the way up to about 3 k a month. And and after these levels, you start getting into tools that are more industry specific or or they they they have very specific tools that work really well for some industries and are just completely unnecessary for other industries. So Siemens Expedition can cost upwards of 70 k for just the the flat program, and then there's a slew of plug ins that you can add to it so you can start getting really expensive. And then the last one I have on the list is Zukin, which before I got into the aerospace industry, I had no clue what it is, but apparently and I and I still actually, honestly, have no clue what it is. I talked to one person who've used it before.

Stephen Kraig:Apparently, Zukin was, Lockheed Martin went to Mentor Graphics, and then and I may be completely wrong here. I've just been told this. But but Lockheed Martin fired Mentor Graphics, went to Zukin and said, if we give you a bunch of money, will you retrofit your software to be what we need it to be? And Zukin was like, I got you. So Zukin is it is it is geared towards what Lockheed Martin needs and with with, like, DOD contracts and things like that.

Stephen Kraig:Zukin is one of the few that doesn't have a sub a subscription service, at this higher level. It's perpetual, and it's around 47100 to 11 k for a perpetual license based off of the plugins you need. So, overall, you can go from the freest of free with no guardrails whatsoever.

Parker Dillmann:With free

Stephen Kraig:All the way up to yeah. Yeah. Right. Right. Free free in free in every possible way all the way up to you need to have a full simulation tools for signal integrity and the craziest field solving software, all spans within this.

Stephen Kraig:So it's the basically, the sky's the limit in terms of how much money you wanna spend on it.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. This is, like, including, like, the newer stuff like GJETEX and all that stuff.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Well, okay. Actually, what's funny is this doesn't include any of the AI EDA tools, which that would be cool to do, like, a comparison sometime in the future about all the AI stuff because these are all, like, the classic guys or the free guys, which some of these even the more expensive ones have not even really been around that long, but some of these have been around for decades.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Even even Zukin is, like, early eighties starting out.

Stephen Kraig:Zukin is a Right.

Parker Dillmann:Is a Japanese company. I had to look that up because I've never heard of that that tool before. You were we were talking about a little bit about before the podcast, and you you said that as you're looking at aerospace jaws for for layout PCB layout, we'll say it requires Zukin experience. It's like, how do you even get that experience? It's

Stephen Kraig:it's super chicken and egg because you only get it if you work at one of those companies, and but they want it before you work at that company. Yeah. Whatever.

Parker Dillmann:I think that's really funny.

Stephen Kraig:So I I I've I've talked to one person who has ever used Zukin before, and, of course, he came from Lockheed Martin. So, hopefully, that just, you know, gives you a little bit of firepower and at least gives you a list of, you know, here's here's some places to go and look if you're if you're starting out or if, like I said, you need to outfit a team and get things get things going. I personally say the real small players are they're great to learn on the big players in I in all the times that I've used the big players, I've always felt like they are perhaps too much. The small or the middle players, like the KiCad, Eagle, dip trace can do way more than you think you can they than you think. So don't just write them off because they don't fit in the big professional land.

Stephen Kraig:Think about them and think about what your company needs and if they can get away with that.

Parker Dillmann:It's really hard to this is the problem with it. It's really hard to change tools mid company to to change because you you're abandoning your libraries. You're banning all your previous designs and and history. K. I'll I'll I'll I actually will say it this way is if you are only planning on having one layout person or that's doing the schematics as well, probably you're gonna be okay with KiCad.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Unless you need unless you need

Parker Dillmann:a feature that Altium has, like some kind of simulation tool, then sure. But if you don't need any of anything beyond a DRC checker, KiCad's gonna be great for you.

Stephen Kraig:You you know, you you'd be surprised that what you get when you go to the higher levels is more control and and and more tools, like you said, simulation and analysis and things like that. But you don't they don't necessarily inherently make a better board. They just have tools that perhaps aid you in making a better board, but not even that. Can you make identical boards in KiCad and Altium? Absolutely.

Stephen Kraig:You could make the exact same board. Now with they'd obviously have slight differences because the programs just don't function identically, but they would the the board would work just the same in in real life. And so so so is is is something like an Altium inherently better than a KiCad? In my opinion, no. Not at all.

Stephen Kraig:Unless it has the tools that you must have to get your your job done. KiCad is likely to not have that kind of a tool. Yeah. And But that doesn't that doesn't make it inferior in any way. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:And that's what I'm saying

Parker Dillmann:is with Altium, if you are planning on having a even if you're starting out with just one engineer, you're planning on having a team of engineers working on boards, then going to a tool like Altium out the gate makes more sense because it gives you more control over your libraries, gives you more control of revision history, that kind of stuff. That is, in my opinion, way more important than, than the EDA tool outputting Gerbers. Right? That's way more important for me as an engineer. And then when you have 10,000 engineers, that's when you start looking at cadence pads, Siemens, Zukin, etcetera.

Stephen Kraig:Right. Right. Right. Right. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:And and at that time, you know, if you have 10,000 engineers, you have a dedicated support team at that company

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:That makes sure that everything's running smoothly.

Parker Dillmann:Yep. And you probably happen to have an entire engineering team that's just handling your package libraries.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, yeah. You know, you have librarians. Yeah. Full of yeah. Absolutely.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So that's why I'm getting that with the scale. Like, where Yeah. Where are you looking at? How many employees you're gonna be having using these tools?

Parker Dillmann:And Right.

Stephen Kraig:Because

Parker Dillmann:if it's just gonna be one person, you can probably and you don't need any of the fancy simulation tools. KiCats gonna work fine. I'd rather go back to Eagle. Oh, on that. Oh, let's wrap this up.

Parker Dillmann:Let's wrap up this

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. We need to. Podcast. My first KeeCad PCB worked 100% correct. Nice.

Parker Dillmann:My first board I ever made in KeeCad. And this is

Stephen Kraig:not a simple board. This is a pretty complicated embedded system, So I'm pretty happy. Well, you know what that speaks to? That that that that means that the tool doesn't necessarily matter. It's the guy driving it that that really makes it matter.

Stephen Kraig:And, also, you have plenty of experience with a bunch of tools, so you know the right questions to ask to get what you need.

Parker Dillmann:Even if those questions make a lot of people 240 characters angry at me.

Stephen Kraig:And with that, thank you for listening to circuit break from MacroFab. We were your hosts, Steven Craig

Parker Dillmann:and Parker Goldman. Take it easy. Later, everyone. Thank you, s u breaker, for downloading our podcast. Tell your friends and coworkers about circuit break, the podcast from Macrofab.

Parker Dillmann:If you have a cool idea, project, or topic you want us to discuss, let Steven, I, and the community of Breakers know. Our community where you can find personal projects, discussions about the podcast, and engineering topics and news, and no politics unlike this episode did. You can find it atform.macfab.com.