- Cy Keener's background in architecture and transition to art and technology.

- The process of designing custom instruments and sensors for Arctic research.

- Challenges of creating durable electronics for extreme environments.

- Collaboration with scientists to document and visualize sea ice and icebergs.

- The artistic process of transforming scientific data into visual art.

- The significance of art in making scientific data accessible and engaging.

- The role of broader impacts in National Science Foundation funding.

- The evolution of Cy's sensor designs from Arduino-based prototypes to advanced devices.

- The use of different materials and technologies for creating resilient enclosures.

- Insights into the conservation of electronic art for future generations.

- Examples of Cy's art installations and exhibitions showcasing Arctic data.

- The importance of merging empirical data with experiential art.

- Cy Keener's portfolio: cykeener.com

- National Science Foundation: nsf.gov

- Make Magazine article on Arduino and Iridium satellite modem: Make Magazine

- Particle devices: Particle.io

- What are your thoughts on the intersection of art and technology in scientific research?

- How do you think visual art can help make complex scientific data more accessible?

- What other natural phenomena would you like to see visualized through art and technology?

Creators and Guests

What is Circuit Break - A MacroFab Podcast?

Dive into the electrifying world of electrical engineering with Circuit Break, a MacroFab podcast hosted by Parker Dillmann and Stephen Kraig. This dynamic duo, armed with practical experience and a palpable passion for tech, explores the latest innovations, industry news, and practical challenges in the field. From DIY project hurdles to deep dives with industry experts, Parker and Stephen's real-world insights provide an engaging learning experience that bridges theory and practice for engineers at any stage of their career.

Whether you're a student eager to grasp what the job market seeks, or an engineer keen to stay ahead in the fast-paced tech world, Circuit Break is your go-to. The hosts, alongside a vibrant community of engineers, makers, and leaders, dissect product evolutions, demystify the journey of tech from lab to market, and reverse engineer the processes behind groundbreaking advancements. Their candid discussions not only enlighten but also inspire listeners to explore the limitless possibilities within electrical engineering.

Presented by MacroFab, a leader in electronics manufacturing services, Circuit Break connects listeners directly to the forefront of PCB design, assembly, and innovation. MacroFab's platform exemplifies the seamless integration of design and manufacturing, catering to a broad audience from hobbyists to professionals.

About the hosts: Parker, an expert in Embedded System Design and DSP, and Stephen, an aficionado of audio electronics and brewing tech, bring a wealth of knowledge and a unique perspective to the show. Their backgrounds in engineering and hands-on projects make each episode a blend of expertise, enthusiasm, and practical advice.

Join the conversation and community at our online engineering forum, where we delve deeper into each episode's content, gather your feedback, and explore the topics you're curious about. Subscribe to Circuit Break on your favorite podcast platform and become part of our journey through the fascinating world of electrical engineering.

Welcome to circuit break from Macrofab, a weekly show about all things engineering, DIY projects, manufacturing, industry news, and Arctic art. We're your hosts, electrical engineers, Parker Dillmann. And Steven Kraig. This is episode 441, and this week is our guest, Cy Keener.

Stephen Kraig:Cy is an interdisciplinary artist focused on recording and representing the natural world. He is an associate professor of sculpture and emerging technology at the University of Maryland. Since 2018, he has collaborated with scientists to document sea ice, icebergs, and glaciers in the Arctic with funding from multiple institutions including the National Science Foundation. His work includes a range of database efforts to visualize diverse phenomena, including ice, wind, rain, and ocean waves. He received a master's of fine arts from the stand from Stanford University and a master of arc architecture from the University of California, Berkeley.

Parker Dillmann:Welcome to the podcast, Sai.

Cy Keener:Yeah. Thanks for having me. It's, it's great to be here. I'm a a fan of the the Macrofab Institution, so I'm, I'm happy to join.

Parker Dillmann:So before we kinda jump into, your current projects and stuff, can you, like, just explain maybe in the context of a of a of a previous project of, like, what do you actually do? Because that's that's that's a big chunk of just words that Steven just just said.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. There's a lot going on there.

Cy Keener:I know. That's the apologies for the the academic. That's, like, simple for academic language, but we gotta we we gotta, like, kinda sound fancy sometimes when we when we describe what we do. Yeah. I mean, I think at the most basic level, what I I have this, kind of incredible privilege of, it kind of runs under the banner of art or art professor, but, basically, I get to design instruments or sensors to at at some level of specificity, and then I get to deploy those in the field.

Cy Keener:So I actually get to travel and do scientific field work in the Arctic has has been the focus for the last little while. And then I get to receive the data that's produced by those sensors, and then I get to create art with that data. So, I think that, you know, most folks are familiar with these models of like data visualization, where you you receive the data that that someone else has generated and then you try to help people understand it. And I feel like I, as an artist, and especially with this arctic stuff, then I have this kind of extra, sort of scope of being able to not just receive environment that I'm out there in, in, experience that environment, think about ways to try to communicate what that's like to other people, and then come up with a sensing system analogies that I use is is it, I think of myself a little bit like a photographer and this is analogy. I'm not, I'm not literally a photographer, but the photographer is out there trying to use a tool, the camera, to capture something that exists in the real world.

Cy Keener:They're making creative decisions and how they capture that and what that looks like, but they're still trying to kind of show you something about the world that exists outside of us. And then I think I'm using the tool set of electrical engineering and some mechanical engineering and, the subject of the environment to try to do something similar.

Parker Dillmann:So so like a photographer, but you're also building the camera.

Cy Keener:Yeah. Absolutely. And I think photographers do that. Or some some photographers do that. And I think that that's that's kind of the I would like to to believe in some way that's the art side that, like, to me, the artists that I really respect out there have, like, you they are people who, if they don't invent their tools, then they're very creative in the the use of existing tools or they're kind of pushing that tool use to some sort of boundary or to the edge of what's possible.

Cy Keener:And then sometimes, sort of creating their own version of tools in order to to accomplish what they're doing.

Stephen Kraig:So so I'm actually curious. Did the did the art come first or did the electronics come first? In other words, did you have an idea and you needed to invent the electronics or did you have the electronics and then figure out some way to incorporate that into art?

Cy Keener:Yeah. That's a great question. For me, I guess I guess the art came first. I've been lucky to be able to kind of, I don't know, like hack away at the at I I think what one of the one of the greatest gifts you can have in any kind of creative career is just sort of longevity or the ability to kind of keep pursuing this thing, whether or not that's just something you're doing in the basement or it's brewing beer or it's making drawings or paintings or whatever, machining parts. Like, there's this kind of, beauty that comes with just being able to do it over a longer period of time.

Cy Keener:And so I had, my my first sort of 3 or 4 years in art was I did not know anything about electronics or coding, and I was basically using architectural design skill set. You mentioned in my bio that I was actually trained as an architect, which just means that I knew how to use CAD and I knew how to make things. And then I actually had a background in construction before architecture, and so I kind of came to architecture as a maker or as a, a person used to to constructing things. And then, even when I was in architecture school, I got to spend a year looking at the way that CNC technology was being incorporated into craft traditions, construction craft traditions, around the world. And, so I kind of brought that skill set to art, and then that looked like we still had a sort of similar subject.

Cy Keener:I was still interested in the environment or just these experiences that I'd had outside, and trying to communicate those. But the the method was more it's what they call installation art, which is where you transform a space. And so it's, you know, people are familiar with painting and sculpture, but then installation art means more just working at a room scale or environmental scale within a building typically, and then you're creating an experience for someone to walk through. So I had a kind of period of of doing that, and then, it was rewarding, but I I wanted. It felt a little bit, like, circular instead of self referential or limited, and and I just really liked, I guess, this idea that I described a few minutes ago of being able to just really see something or, like, represent or represent something about the real world and that sort of the the real world is way more complex than any interesting than any ideas that I have in my head about it.

Cy Keener:And so I see sensors like basically, you know, sensors from an EE perspective, allow us to see and hear and experience things that we cannot with our senses, like with our our kind of 5 human senses. And so I think that that was really the attraction, that drew me into, going back to school for art. And then I basically I went to school for art at an engineering school, and then I used that time to take, like, basic atmospheric science and oceanography and then mechanical engineering product design, and then also, like a sensor network class, like a civil and environmental engineering network class that had some basic signal processing content. And then but I I learned electronics and I learned coding in our context. So it was actually, from my art professors, that and using the the Arduino environment that I came into, like, that skill set.

Stephen Kraig:So why the Arctic?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. You you mentioned a bit, you took some oceanography classes too.

Cy Keener:Yeah. I think there's, you know, some of the some of the things that you choose in your career, I feel like you you kind of I don't know. Some some of the things are are kind of circumstantial, and then some things are are intentional. But I guess that the maybe the evolution, of my sensor projects as an artist was was kind of it's maybe it's worth talking about, but the the very first large scale sensor project that I did, it was kind of trying to get to that installation scale, was I put 30 wind speed and direction sensors out in this field, that Stanford maintained and that had a good Wi Fi access and had power. So it was this kind of biological preserve.

Cy Keener:And so I put 30 of these wind speed and direction sensors out fairly close to each other in a grid, in an array. And then I had 30, lights on servos that were at a gallery space about 4 miles away back at campus, and then each of the wind speed and direction sensors was indexed to one of the lights. So it basically created this array, like a, vector field of the wind. So that the whole idea there was to basically, you you stand in a field of grass and you get to watch the wind cross the field and you get to see all the kind of intricate patterns that the that the wind makes. And then this was a art piece that was an attempt to visualize that or to kind of re, sort of do that in a technical means as opposed to just taking video of the grass or something like that.

Cy Keener:So that one, I I got to use a bunch of try to do an array of 30 sensors, which is really hard to do. There's just always things breaking, but it was still dependent on Wi Fi and power. There was, I got basically an outhouse that was nearby that had a power outlet, and so it ran off of that. And then I still had to do one more project, as part of my master's degree, and so I just I kinda wanted to see how far I could take that. Like, could I improve on that?

Cy Keener:And then the the idea that I had was to put things in the ocean and then to switch to battery, solar, and, satellite communication. And there is a article that came out in Make Magazine, and this kind of short article that just pointed the way to do that with Arduino and a Iridium satellite modem and a GPS. And so I I kinda went down that path, and then I think that was sorta 2016 ish. And then when I showed up to to start working as a professor here in Maryland, Washington DC is a really great area because we have NOAA, NASA, and all these other folks nearby, and I ended up making connection with, somebody at the National Ice Center. There's a a place that the federal government and maritime safety and and defense, and, and that to sort of open the door to, and that to sort of open the door to, being able to go to the Arctic or being able to kind of think about making sensors for the Arctic and kind of adapt this PCB and circuit and some code that I'd been working on from a kind of warm ocean environment to a cold ocean environment.

Cy Keener:And then I just poured all my energy into that, and then that's what kind of turned into this longer term collaboration, with a group of scientists that I've that's now kinda coming up on 5 years. And so so yeah. And I think the Arctic like, I grew up in the Pacific Northwest. I grew up in Seattle, and I had access to to mountains and glaciers and some of that outdoor stuff when I was growing up. And then the Arctic Before I started going there, it felt like some kind of mythical place that people didn't really get to experience, but you, like, saw the National Geographic movies.

Cy Keener:And then, just getting to experience that firsthand was pretty powerful. And, I just did everything I could to make myself useful to that group and to try to to really, just become a part of their team. And so at this point, I'm I'm, basically their self appointed, like, r and d division. So scientists are always trying to they always wanna do new things and measure new things or try out new ideas, but they don't really have the time to, create new instruments. And, then the option is the off the shelf options from different commercial companies are kinda limited.

Cy Keener:So, my strange skill set, like, my formal title is sculpture and emerging technology, which doesn't mean that much to anyone, but I I do this mix of electrical engineering, kind of mechanical engineering, and then enclosure design. So it's basically just all of the same, like, that same consumer electronic skill set that goes into any product. And I just do that for I've I've basically prototype. Like, I I prototype instruments, is is my contribution, and do kind of low low production runs of different instruments that hopefully enable the scientists to do what they're doing better or to do things in a in an improved way or a slightly different way.

Parker Dillmann:Well, let's, let's dig into the electronics then. So I guess let's let's talk about, like, what the current iteration and then maybe, like, the history leading up to it. Like how did you go from an Arduino into something that can survive, in the water in the Arctic? That's that because that's its own set of engineering challenges.

Cy Keener:Yeah. And I would I, I approach that very humbly in the sense that that the Arctic is a is a pretty harsh environment, and I would never kind of say that I've solved that problem. I think we're kind of continually trying to to improve on our our longevity of the instruments. But, yeah, the development of that was super fun. So, I guess I started with that Make Magazine article, and then in, in, in art school, I basically taught myself, how to build, I guess, like, PCBs for, breakout boards.

Cy Keener:So, like, basically, just like a I don't know what the kind of correct term for that is, but just like a a PCB that would have a bunch of headers and and fixed routing on it so that you could plug in, like, you know, your Arduino Nano plus the GPS plus some sort of sensor, and then they would all talk to each other and be a little bit more robust than just a bunch of junk soldered together, with wires. And so I I taught myself how to use Eagle using a book, and then I the art method is is really project based and experiential. You just kind of try and fail and then try again. And I had a adviser, at Stanford who has been doing art and electronics for, I guess, close to 45 or 50 years now. And he was actually at Atari, in the early days, and he was at Xerox PARC.

Cy Keener:And so I think I think that there's this like, most of the EE community probably doesn't know, but there's a there's actually a pretty strong history of artists working in electronics and at these different organizations over the years. So, I would get as far as I could get, and then I would run next door to his studio. Instead of calling them labs, we call them studios in art, and I would run next door with my questions. And kinda I would say that save up all my questions because I didn't wanna be there every 5 minutes, and then I would just kinda run next door and he would, like, tell me what to do or how to solve this stuff. Yeah.

Cy Keener:So I I got some traction out of that and just it was a really a great time and place to also be doing that stuff. Like, I was at Stanford. I think RadioShack was, like, just about to go out of business, the local RadioShack, and then we had this JMCO, electronics. So I could just get in the car and cruise 20 minutes down the freeway and be able to pick up stuff. And I would I would submit these, like, bare bones PCBs to Bay Area Circuits at, like, 4 PM, and then I would be there, like, lurking in their parking lot the next day waiting for my email to the the circuit was ready and

Parker Dillmann:Imagine you, like, peering into the blinds.

Cy Keener:Yeah. I was, like, usually, they emailed me around 4. So I'll be there at, like, 355. And, Yeah. So it's just this kind of amazing and and fun period of of figuring that stuff out through trial and error, but with really good support from some knowledgeable folks.

Cy Keener:So that I think that was kinda phase 1, and then that yielded these different, sort of plug and play, like, PCBs. And then when the arctic, like, opportunity came up, then I spent about 6 months. I was like, oh, I gotta up my game. I need to do my first, like, full surface mount PCB What? And, like, a standalone PCB.

Cy Keener:Yeah. Go ahead.

Parker Dillmann:Is when because you jumped from you know, you're doing these projects, with Stanford and stuff and then to the Arctic. How did I know you said you met some people that like, some scientists that were working up there, but how did that conversation actually go? Like, the Yeah. Like, was it like you just, like, chilling at a bar with them and then they're like, man, these sensors that we have are they suck.

Stephen Kraig:Or or

Parker Dillmann:or was it more like you pitch what you can do?

Cy Keener:That's a really great question. Yeah. So I work at the University of Maryland. And at the time when I showed up, then they had somebody whose job was to try to connect you with people who you didn't know, but you but might be, like, good collaborators.

Parker Dillmann:Like synergy kind of stuff?

Cy Keener:Yeah. Or just,

Parker Dillmann:yeah.

Cy Keener:I mean, I think Synergy is right, but then also just somebody you could actually, like, do projects with or something. So I I was actually I was looking for somebody that could help me with, I guess, access and also just more technical expertise related to glaciers. And then I got put in touch with this really wonderful guy, John Woods, who at the time was at the National Ice Center, but he had been a meteorology and oceanography officer in the Navy. And then he had actually taught at the part of his active duty was teaching undergrads at the Naval Academy. So the Naval Academy Annapolis is just, just outside of town here.

Cy Keener:He had spent, like, a year of his life working on, building buoys using Arduino and Raspberry Pi stuff with these undergrads as a capstone project. So the Naval Academy does these really ambitious capstone projects. Like, they'll launch cube satellites. They'll, they'll do these pretty technical kind of things. And, and so we actually just bonded over like, I got an introduction to him, and then we bonded over just kind of trying to figure all this stuff out in a Arduino slash Raspberry Pi environment.

Cy Keener:I think he had, like, a little bit more sophisticated, approach to it technically, but he wasn't really he was more, like, managing that. Like, there was somebody at the Stanford Research Institute, just kinda coincidentally, that was that was kinda doing his coding and his hardware dev for him. But he had just kinda had this experience and we bonded over that and just trying to get stuff to work out there. So Like, if it just getting stuff to work out there is really hard. So so that was my end, and then I I basically, like, committed myself to, to trying to contribute to what he was doing.

Cy Keener:And initially, it was more like, I'll just send the instruments, but then he could see just all the work I was putting into it. And I I had this background in climbing and kind of outdoor stuff. And so I was just like, hey, you know, if if you ever get a chance to let me join, like, I'd be excited to join. And so it was actually I met him in July or August, and then it was, like, March of the next year that I was actually in the Arctic for the first time with this science team.

Stephen Kraig:Oh, that's cool.

Cy Keener:Which is a pretty pretty quick turnaround. Super lucky. I didn't know at the time, but he actually had a whole track record of enabling that kind of access. So there's he had actually let, this this, woman artist who does these really beautiful glacial kind of paintings, like, on these NASA flights, so that she could take pictures and kinda see these, like, these NASA overflights of Greenland and Arctic and and stuff like that. So I think that, you know, the scientific community is kinda open to the right folks and and I think that maybe one other practical thing I'll throw in here is that the the National Science Foundation is when you submit a proposal to them, it's competitive, but you're judged on the science that you're doing.

Cy Keener:They call that the intellectual merit, but you're also judged on your ability to share that with the public. And they get the term that they have for that is called broader impacts. But basically, they're saying it's not good enough for you just to do the science, but you have to also basically try to tell the taxpayer why it's worth doing or like what's exciting about it. And so that's that's kind of been my, that's my I feel like if I have a superpower as an artist, it's like my ability to collaborate with scientists and then to, to that allows me to also have access to funding. That is like, I I get kind of like a small portion of what they get, but for an artist, it's like a huge amount.

Cy Keener:Right. So, there's, like, there's kind of like different different scales at work there.

Stephen Kraig:Do do you find

Parker Dillmann:that Yeah.

Cy Keener:So that's sorry. It's kind of a long explanation, but I think that that's it's it's like a human it's just a human thing, like, I got introduced to somebody, and I just worked really hard to try to, to, be a part of the team, basically.

Stephen Kraig:Is that part, do you find that part difficult, the justification of the project?

Cy Keener:Oh, gosh. I mean, I feel like once you once you decide you're an artist and justification is kinda out the window. Like, you're you're sort of

Stephen Kraig:Well, but but but but just be like, it's cool.

Parker Dillmann:Let me do it because it's

Stephen Kraig:cool. Well, but but but even even you saying it to the taxpayer justification to the taxpayer can be an uphill battle. Right? I I I did a little bit of, audio no. Sorry.

Stephen Kraig:I did a little bit of art electronics with a collaborative group back in Houston, and and it was very difficult for us to find funding, because it was very difficult for us to, I guess, you could say prove to a place that, hey. This this is going to be a thing that brings, I don't know, brings something to the table. I don't even know how what to what to say about it, but it was very difficult for us.

Cy Keener:Yeah. And I and I think that's an open conversation. There there is a movement, to to kind of promote or or to kinda explore this idea of arts based research. So there's actually been, there's been a movement to try to say that the arts approach can produce knowledge. Like, it's not just about data visualization.

Cy Keener:So there's there's sort of groups of folks out there that are really trying to say that this arts approach actually has something positive to, to provide or to kind of share with the public. And I feel like within my own work, then that's the ability like, almost everything that I make on the art side or in the the kind of exhibition side is is at a human scale. So I'm really interested in not like, we all know what it's like to look at a graph, and we all know what it's like to to sort of receive information intellectually. But, like, one one of my art pieces, it takes, light and temperature sensors throughout, basically, like a core of active sea ice that's out there in the ocean that's 5 foot thick. And then it receives that data by a satellite, and then it recreates that data at full scale, a one to one scale using about a 1000 LEDs in this tube.

Cy Keener:And so then the idea is that you can stand next to this tube of LED light, and you can experience the colors, the RGB colors for exactly what they are in the ice that day with, like, 4 hour latency or whatever. And then you can sort of experience it as an embodied human, which is a totally different thing than sort of, like, reading some chart or some graph or something like that. So I think I think that it's we're not after like, I will never tell you that artists are trying to produce the same thing as scientific information or it's a it's like a different mode, but I think that there's there's different ways that we understand things. Like, we understand things through experience. And and just like in engineering, there's there's a empirical approach to understanding things.

Cy Keener:So there's there's the data sheet calculation approach, and they both have their their value and their their kind of time and place. And so I think that I'm a little bit more on that, like using data to create this empirical approach. Another art piece that I have takes, wave readings from the ocean, and then it projects a laser line around the room. So it's more of like a mechatronic piece, but it the idea with that is just that you can experience the the kind of mood of the ocean through the this horizon line shifting up and down. So I I think that I'm really after, like, in some of my work, I'm after really trying to to sort of share this experience of the place or kind of have it be this embodied experience.

Cy Keener:But I also that's that's, like, the the kind of ambitious art side to my work, but I'm also pretty conservative in the sense that it's I feel like it's a great privilege to get to ride along with these scientists, and I wanna contribute to their core mission, and not just be there as, like, an art kinda add on that, like, is gonna get cut when the budget gets cut or something. And so I actually use the this kind of, like, low cost IoT Arduino approach to try to build instruments that contribute to their core mission. So the group that I work with is the International Arctic Buoy Program, and they're responsible for putting the sensors on the Arctic Ocean that contribute to numerical weather prediction, which is just a fancy term for, like, the weather forecast. So if you were seeing the tornado or, like, the hurricane prediction, then then the hurricane path or all that. There's, like, the American weather model.

Cy Keener:There's the European weather model. The the Arctic Ocean is the size of the United States, and it has whatever sensors the group that I work with can put out there, which is typically, like, a 150 to 200 at any one time. And then the United States, like, the land mass has about a quarter million weather sensors. So there's a huge difference in, the kind of quality and the the, amount of data that goes into those systems. So, yeah.

Cy Keener:So the the kind of bread and butter funding wise for what we do is is getting a pressure sensor and a temperature sensor on the surface of the Arctic Ocean in as many places as possible, and that's what drives the the weather models. So I think I have a there's, like, a maybe that sort of romantic side of me that likes to to do the art stuff, but then I also want to I wanna be on the plane when it takes off. I wanna be part of the mission critical team and and get to go out there and see that stuff. And so I I do both, you know, I I try to to contribute to the the full effort.

Stephen Kraig:So so as of right now, there's I don't know. What I don't if you mentioned the number, but there's a number of Arduinos surviving up in the Arctic. I I'm I I looked up the the temperature range of of an Arduino, and they're technically rated down to negative 40 c and the average arctic temperature is like negative 12. So technically it's within range but I I would have never expected that an Arduino would survive up there. That's that's fascinating and I love that you're contributing to that kind of knowledge.

Stephen Kraig:It's just yeah. You can use an Arduino extensively up there. It were in that kind of environment.

Cy Keener:Yeah. No. The I mean, this the circuit development was fun. I mean, it basically, it basically comes down to just creating a device that is as low power as possible, and it can work on a wide range of voltages. So, the, I guess, that the the kind of engineering answer to an Arctic battery is this thing.

Cy Keener:It's a lithium thionyl chloride battery. It's like this weird, chemical composition, but it's like, Tataran is the company that makes it. So this is more, like, military grade batteries. And then that's the one battery that is sort of approved to operate down to minus 40, and it's gonna, it's gonna work for you at all times. But that battery, you cannot bring on a passenger airplane.

Cy Keener:So it's, like, really amazing from an engineering perspective, but, like, almost completely useless from, like, getting it into the field perspective. And even if you commit to that battery, like, some of my first devices that I deployed had that battery, But even if you commit to it, you still it still has a a pretty radical voltage drop over that, temperature range. So I think that the the one that I was using was sort of like 3.9 at, like room temperature, and then it would get down to, like, 2.7 or something like that at a at the minus 40 temperature. And it has to have it has to be custom made. It has to have this capacitor if you're gonna use it for, like, Sherpa's data or any of the, like, Iridium communication and all these kind of complications.

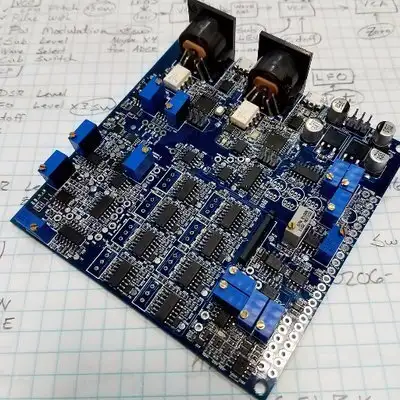

Cy Keener:And then a lot of the folks in Arctic science actually just end up using alkaline cells, which I think we we all kind of dismiss as being, kind of low tech or not good in the cold, but, the I don't know. The know. The oceanographic community just has pretty good luck with the alkaline cells, operating, and they also have that pretty radical voltage drop, that that takes place over that temperature range. But but yeah. I mean, I think all of the like, when I say Arduino, then I'm in the current status of my board, like, the PCB that I've been working on since about 2018, I I call it the ice drifter.

Cy Keener:I'm not quite sure how we got to that name. I think it was just, like, a a project name that stuck around. But, but that thing is a, it's a ATmega 6441284. So it's basically, we started with the 328 and ran out of room. So we basically just, like, started with an Arduino Uno and then ran out of room for what we were trying to do on there.

Cy Keener:It has a a TI boost circuit. So the, the so the cool thing about the the ATmega series is that they they can run just on raw battery power with a pretty crazy voltage range. I I forget what it is, but it's, like, 1.8 to 5 something. So you actually don't have to to condition or regulate that power over a pretty wide range. So I have that thing just hooked up to direct battery power.

Cy Keener:I have all my kinda peripheral stuff switched, just with, enable pins on voltage regulators. And so I it it's going into, like, a kinda poor timer, just like watchdog timer sleep mode. For an hour, it's waking back up. It's, querying the GPS and finding out what time it is, finding out if it's supposed to do stuff or just go back to sleep. And then, if it does if it is time for it to do something, then it goes around, and it it does a barometric pressure, external temperature, and fires up the GPS to get a location.

Cy Keener:And then it shuts all that down, and then it fires up the boost circuit, which, which enables the Iridium satellite modem. I've been mostly using these Iridium, or these these other PCBs produced by a company called rockbroc rock Block. I think they changed it ground control, but basically this, they came up with a just a support PCB for the Iridium modem. And we found in theory, it has a battery pin, but we found that it was unreliable without that TI boost, getting it up to 5 volts. So, yeah, so that's kind of the range.

Cy Keener:Like, we've tested it down to 2.7 volts, and I've got one that's been sitting at this test table in the Arctic. I was looking at it last night, and I think it it's at, like, 28 100 transmits or something, and that's at a twice per day cycle. So that thing's been transmitting for, like, 3 years now, and that's in literally the northernmost point of Alaska. I think it's around 72 degrees north, And it it it's on a on a table about, you know, about a quarter mile from the ocean, up by this NOAA station there. And, I've swapped the battery on it, but the the PCB and the modem have just been running since, I don't know, about 2021 sometime.

Cy Keener:So yeah. So it's not it's it's like a bunch of Arduino code. It's a bunch of open source circuits that I kinda hacked, or I I would basically just get rid of all the stuff that I didn't want, add in some, some power management, and then try to make the board somewhat condensed. Yeah. And just just improve that over time.

Cy Keener:Had really good mentors that would, you know, I would make my version of it, and then they would look at it and laugh and tell me all the things I did wrong and send me back a bunch of notes. And, I would make revisions. And, eventually, that went all the way to the silk screen where my my friend was like, look, man. You just gotta you gotta do a better job with the silk screen. This thing looks like shit.

Cy Keener:So, he's also a designer and an artist. He's like, he does EE stuff, but, yeah. So I think it's a yeah. So, like, that's been kind of the journey. I actually hand built, probably the first 30 units of, like, 3 or 4 revs of that.

Cy Keener:And then, switching over to Macrofab was, like, my big my step up to the big leagues where I got a little bit of science money, and I was able to, to do like, like, I I was kinda like a OSH Park, OSH OSH stencil, like, hand build on the target Teflon hot plate kinda guy, for a while, and then, yeah, and then switched over. I think even when I started on that board, I brought in all of the the macro fab and house parts into the into the Eagle library, and I was specifically just like, okay. These guys are I'll I'll kinda offload whatever parts are a thing that I can to these guys and then, just go after my my primary components. So

Parker Dillmann:That that's that's interesting to hear. So that means that footprints that Steven and I designed are in the Arctic because Steven and I worked on that Absolutely, man. Steven and I worked on that part library.

Stephen Kraig:That was that was a while ago. A long time ago. Yeah.

Cy Keener:Yeah. Is it is it okay that I'm still using it? Oh, yeah. Is anybody using it? Okay.

Cy Keener:Good. I I just think it's that

Parker Dillmann:this is the first time we've talked to someone who's used them.

Cy Keener:Oh, alright. On the podcast.

Parker Dillmann:I I imagine as people are using them because I I use them all the time. So

Cy Keener:Yeah. No. I think I think they're great, and I think I have because I lacked, like, 5 years of EE formal training, then I I have, like, a I think of it kind of like a superstitious approach where it's like, if this worked for somebody else, then there's a chance it's gonna work for me. And so any anything I can do to kinda triangulate and validate, like, this is the, you know, this is a part that I'm working with someone else's sort of proven results, then I will take it. I will take it for sure.

Cy Keener:Yeah. And then in, like, 10 days, I'm going back to we have this really great gig with the Air National Guard in Anchorage right now. I think I said I shared some of these images with your support team when I got stuck in needing their help back in January. And, yeah. So I think in in, like, 10 days or something, I'll head back to Alaska, and we've actually got a version of the buoy that, can survive getting thrown out of airplane and have a parachute open and then land on the ice and then operate from the ice and the the open ocean once the ice melts.

Cy Keener:So there's another 8 of those those macro fab library circuits are gonna get thrown out the airplane here in about 14 days.

Parker Dillmann:So So so I wanna I wanna talk about the, oh, because because you've been developing this this hardware for about 5 years now. How has it changed? What what have you learned over those 5 years to make the circuit better?

Cy Keener:Oh, man. I mean, I think that the the the hard spot was I just went through the I went through a mild version of the pandemic part shortage just like all of everyone else did. And I think that that, that kinda made it just difficult to keep producing the thing. And then then I made some yeah. I mean, you can just laugh at me for a minute, but I made some really dumb, mistakes and then had to kinda fix them.

Cy Keener:But one of them was that if you're if you're coming at this kind of from the outside, like, you just really like LED lights that tell you that it's working. And so for maybe, like, the first 4 or 5 years, I I was trying to do this ultra low power device, but I had a LED light that I couldn't disable. It took me a while to so I basically had, like, a LED light in a dark box in the Arctic and it was using up, like, half my battery. So so the most the most recent rev actually has, it has, some pins that that you can, connect and then turn the LED light on, but it doesn't come, like, naturally powered. We've had to swap the, the pressure sensor, like I switch from a Bosch BMP280 to this TE sensor that's, part of that was just due to some parts shortage stuff.

Cy Keener:But then also, this TE sensor actually has this kind of nice stainless steel, mount that you can put an o ring on. So you can actually put, like, a tube down to it, which is kinda cool. And then, I'm sort of slacking, but I I would like to I think I think that the thing that I would definitely wanna change on it moving forward is just upgrading the processing power. Like, we're we would, I've had plans for, like, 2 or 3 years to make us the MD 21 version of it. And the, you know, the the ATmega works fine, but it just feels like using an ATmega in 2024 is, like, slightly strange thing to do when there's there's other options out there.

Cy Keener:So I think there's that. The big the big project that I'm trying to take on is is that I've been using these sensors. Like we will do these kind of peripherals with it. So the circuit has the ability to to communicate over serial or ITC to other devices. And so, a bunch of the work that I've done in the Arctic, has involved temperature and light sensors created by a Croatian company, that are these kind of custom sensors for Arctic applications, and they're they're basically like a flex PCB with a bunch of little thermistors or a bunch of RGB IR sensors at like a 2 centimeter or 5 centimeter increment, and you put those down through the ice.

Cy Keener:But basically, we've had to, to do that. We would like, they had their own ATmega 328 board that would talk to the sensors and that it would communicate back and forth to my ATmega board over serial and kinda send the data then do that. But we'd like to kinda bring that in house. So I've I've got sorta unrealized designs to to try to bring that in house. I also spent a bunch of time, sorting out my own Iridium support board, and I got that to end build stage, but then I haven't kind of done a full I got that working at that stage, but I haven't done, like, a full production run of that and gotten that out into the Arctic.

Cy Keener:So there's a bunch of like, I guess my problem as an artist is that I I have, like, too wide of a skill set or something or, like, too many ambitions to do different things, and then it just kinda goes in cycles. But I would love to to carve out 6 months just to to kinda crank out 3 or 4 iterations of like, future iterations of the thing. So so, yeah, I mean, I think I think it in some ways I've just experienced all the same that sort of, like, design for manufacturing and parts shortage stuff on a smaller scale that, that everyone else has experienced and kinda struggled with.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Having too much to do is about you're at home here.

Cy Keener:Yeah. I get that. I I listen to to you guys a little bit, and I I, I get that. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:That's not a bad thing.

Cy Keener:I think no. I agree with you. I think it's a it's a good thing for sure. But I think you went on one of the the the snippets I listened to. You said you can't talk about projects unless they're over 50 percent done.

Cy Keener:So I think I might have just broken the rule on 1 of those

Stephen Kraig:1

Cy Keener:or 2 of those projects. So apologies.

Stephen Kraig:We've been trying really hard to stick to that rule. Yeah.

Cy Keener:It's easy to have good ideas. You know, a lot of people have good ideas. Yes. It's hard to have a working circuit. So So,

Parker Dillmann:Sai, I wanna talk about the enclosure, now. Yeah. So because you now have a new version. So I wanna talk about the old version and maybe, like, the first iteration of how, like, it came the enclosure came about to survive the arctic Mhmm. And then up to the current version that now you can just like yeet it out of a plane and

Stephen Kraig:it's fine.

Cy Keener:Yeah. I don't I think that that path has been pretty windy but I think that the yeah. I mean, the the forces up there are kinda tricky. There's the cold that we've talked about, but then, one of the biggest hurdles is that that the Arctic has this stuff called sea ice. Sea ice forms on the surface of the ocean just like it forms on a lake.

Cy Keener:So it's actually, like, starting on the surface and then thickening from the air. And then that stuff moves around on the surface of the ocean. So there's obviously ocean currents and then there's wind. And so then that stuff kind of moves around and collides into itself and makes this whole crazy landscape. But there's a there's a ton of crushing forces, with all that.

Cy Keener:So your your kind of ideal enclosure has to operate in the cold, but it also has to absorb, like, I don't know, thousands of pound blocks of stuff coming together and trying to crush it. Like, it's a it's a pretty, impossible task to really just solve. I think the the buoys that, that really last for 3 to 5 years are solving that almost at, like, a small boat scale, which I'm not really interested in working at. But when we, like, when we go to Alaska in a couple of weeks, we'll be putting some of these buoys out that weigh a £180, and they actually have, like, a fiberglass hole that's equivalent to kind of, like, a small, a small boat. And that hole is pretty good at kind of, like, rising up out of ice and surviving all that.

Cy Keener:And then we also there's another smaller scale sort of, like, beach ball scale, like, 30 pound buoy that is just a sphere. So I think the sphere is, like, a pretty good shape, for for surviving all that that kind of crushing forces. And, so those are the defaults, and then our our super lazy, enclosure is a Pelican box. So so that's kind of, like, the opposite of extremes. On the one side, we have, like, a $40,000 custom made thing that's made by a ship, like a small boat making company.

Cy Keener:And then on the other side, if we're just trying to see if something works, then we'll use a Pelican box, and try to test that. And then my my enclosures kinda fall in between there. I think in the earlier days, then a lot of my enclosures were, kind of riff on that that hemispheres or kind of 2 hemispheres with a o ring, and some sort of clamping force, like some a bunch of bolts and then the different sealing approaches using, like I don't know, like 3 ms makes this below the water line sealant that's kind of like a caulk, and all these kind of things. And then I spent the last year working on a a tube buoy. So we actually, there's this whole other group up in New Hampshire that has been making these 10 or 12 foot long tube buoys that use, 4 inch, either historically they use 4 inch PVC pipe and then the more recent ones use ABS pipe.

Cy Keener:You're basically just going to Home Depot or Lowe's and you're buying like 4 inch pipe and then they're you're building a buoy around that. They have So that's what the air

Parker Dillmann:They have Arctic rated PVC pipe?

Cy Keener:They they don't. You end up you end up to I mean, it's just like Arturopeo. Right? You end up with this mash up of, like, kind of high spec stuff and then just kinda, like, whatever was laying around.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I I I I like that, yeah, the mil spec battery that probably cost a lot and has a long lead time and then Home Depot pipe.

Cy Keener:Yeah. Yeah. I mean, my my equivalent of that for the first round of these, it was that I would buy this $150 chunk of ABS, this, like, inch and a half, what 12 by 12 inch chunk of ABS from McMaster Carr. And then I would pay these, like, these instructional fab labs, these, like, undergrad labs to c and c that thing. And then and then I would attach that to, like, $5 a pipe.

Cy Keener:It was my way of, like, trying to to just be like, okay. I know that I I will have this, like, custom part, that needs to absorb a bunch of forces in it. I want it to be, like, ABS proper. But now we're we've been just evolving that design. I haven't been doing that on my own.

Cy Keener:It's been one of the great things about the end of the university is that I get to collaborate a bunch, and so I've actually been working on that design with a group of undergrad aerospace students for the last year. So I I ran a cohort of 5 or 6, and then one of the one of them is just super talented at at kind of part design. And so he and I have been moving that thing forward, and it's almost all, ABS 3 d prints at this point. So we've kind of figured out ways of pulling a lot of the forces, like like, putting the forces into the tube and kind of pulling them out of custom parts. And then, this weird German company came up with this, chemical that you can bathe FDM prints in, and it makes them suitable for underwater applications.

Cy Keener:So it sort of, like, heals all the layers. And so we've been testing that for, like, the last 3 or 4 months, and then, 3 m makes this other, like, really MasterCar sells it as, like, a fire resistant wire repair coating, but it's, it's this really amazing, resin that you can basically just use a thin layer of to kind of seal things. And then the underwater robotics community uses that stuff as, like, duct tape or whatever. Like, if there's ever a problem, then you just put this this, like, 3 m product on it, and it's solved as far as, like It

Stephen Kraig:just fixed.

Cy Keener:Waterproofing things at depth. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Is it Flex Seal?

Cy Keener:Is it? No. It's, but I I wouldn't like, I don't wanna admit this in public, but I I may have used Flex Seal on other projects. It makes, like, not a not a terrible, not a terrible, option for some ceiling stuff. But, yeah, I forget this.

Cy Keener:It's something cast, but this this, 3 m product is so now our current thing is, like, the ABS pipe is these treated, ABS FDM prints, and then there's this, like, this 3 d three m, like, resin product that goes over the top of that. And then we have some some water jet cut rings that are for the parachute attachment and trying to get the parachute to detach from it. Yeah. But I think our goal, you know, like, the the Norwegians make one of these ice buoys that's in the $30,000 range. This other American company that's kinda like boat maker makes these $40,000 buoys, and then our job or my goal is always to sort of make something that's in the, like I think my electronics with the Iridium modem and the battery and stuff probably cost around $500.

Cy Keener:And then if I can hit something more like $1,000 of course, this excludes time, so it's you gotta be careful. But I have a I work at the university and my time is, like, covered by by them and then so I'm I'm aiming for this more, like, $1,000, like, bomb cost, I guess, to to try to replace an instrument that typically costs more, like, 35100 to 40,000 or whatever. So I think that's what the Arduino, like, community and then you guys as well kinda opened up and just kinda made it possible is that, like, you know, 20 years ago, I would have had to be a full EE and, in order to have any effectiveness in this in these areas. But I think that that these communities, have really kinda opened access to folks like me. Yeah.

Cy Keener:But enclosures are hard, and I I feel like I'm still I'm still learning, and we're still we're still testing.

Stephen Kraig:You know, we're we're about 50, 52 minutes into this episode, and I feel like we could go a whole another episode talking about the art side of things, but but I think I think it would be, I think we need to touch on that at least just a little bit here. So so the actual presentation of what you are doing with the data, can you talk about that? Is it are are you doing gallery shows, or what does it actually look like?

Cy Keener:Yeah. I think I did a series of electronic art pieces, like, that probably doesn't mean that much to your audience. But I did a series of, like, of more, like, light and motor or mechatronic pieces. So that was, like, the wind, that kind of wind vector, piece. There was, that ocean wave piece and then this, LED light piece that worked off of the basically like this digital ICE core.

Cy Keener:So I feel like I have that kind of one range, and then the other range is trying to take some of the data, that we get and then put it kind of back into more of a a fixed sculpture or a drawing of some sort. So, those I guess there's there's mechatronic pieces. Like, those have to be installed. Like, they're they're pretty hard to run, and they're always trying to break. And, you have to, like, fly to a place and install them in a special room and then kind of babysit them for the show.

Parker Dillmann:I I I do like how you said they try to break. Not that they not just they break, but they try to break.

Cy Keener:Yep. Yeah. I mean, you're that first the first the first large scale piece I did, it had 30 separate did you guys ever heard of the particle particle dot io? Mhmm. It was these guys that Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I know. We had them on the podcast.

Cy Keener:Oh, okay. Great. Yeah. Zach and Zach maybe or I'm not sure who yet. But anyway but they they supported, like, my first big Arduino piece and it basically had 30 of their particle devices in the field, each one of those talking to 2 sensors, a wind speed and direction sensor.

Cy Keener:And then I have 30 of their particle devices in the gallery, each running 2 servos, lights, and I guess that was it. It feels like there's one other variable there. But so that's basically 60 separate Arduinos and a 120 sensors. We lost them. We lost them.

Parker Dillmann:That's all it said. Oh.

Stephen Kraig:The Arctic has claimed him.

Parker Dillmann:Hello. You're back.

Cy Keener:Can you guys hear me? Yep. Okay. I'm sorry. Anyway, but, yeah, though, this is this thing just had it had 60 separate Arduino type things.

Cy Keener:There are particle devices, it had a 120 sensors, and then it on the other side, it had a 120 lights and a 120 servos, so everything was breaking all the time. Like, there's just no way that you're gonna get all of those things to work, over a 3 month run. So I guess it in art, it feels like 3 months is kind of like a a reasonable time to do an electronic art piece. And so so that's really hard. And and then I think over time then a lot of a lot of my kind of I don't wanna call it expertise, but a lot of my maturity or a lot of the effort that I put into the electric art pieces is actually just trying to make them reliable.

Cy Keener:Like, so you you it's, like, easy to to get a 30 second demo for YouTube. Like, I don't post on YouTube, but, like, it's easy to get a 30 second demo of something working, and it's really hard to get it to run every every day or 5 days a week in a gallery for 3 months. And then the the approaches that you use for those two things are pretty different. And so yeah. So I think that that's a whole aspect of my art, is really that kind of using lights and motors to enact things.

Cy Keener:And then I think the other side of my art is is the kind of taking that historic data and then trying to present it in a static way, but in another way that's kinda compelling. So I did I had a, show at the National Academy of Sciences, which is this place in Washington, DC, and then I'm gonna be kinda redoing a bunch of that work for a show in Michigan, that'll be next year. But that had this these kind of beautiful, sculptures where each one had 7 there are there are 10 different of these kind of, like, custom machine trays, that hung from the wall. They're about 16 inches by 8 feet tall, and each one of those kind of aluminum trays had 7 different, time instances of this digital ice core. So they were, like, very kind of carefully printed colors on acrylic, and then it had the actual thermistor, like, data printed and the RGB data printed.

Cy Keener:And then those were at this kind of 45 degree angle so that as you moved around it, you could kinda see light shift through it. So, so that's not a live data piece. Like, some of my work is more in this live data side, and then that's a little bit

Stephen Kraig:more of

Cy Keener:a in some ways, it's just me trying to be more practical, like, having something that you can ship and and have somebody hang on the wall and that actually sticks around and isn't just in art, they have this word called conservation, which is, like, the word for like, people think of conservation as, like, someone retouching a Michelangelo painting on the, like, Sistine Chapel, but it also exists for, electronic art where they're basically, like, this this is a beautiful electronic art piece, but, like, how are we gonna show this 20 years from now? Like, are we just gonna abandon the entire, like, 20 year old technology and remake it with the same intentions? Or are we gonna try to, like, go around and buy up TVs from the eighties in order to, like, show this piece, like, 5 years from now or there's this whole kind of conversation where we think, you know, we we encounter, like, end of life and and all of these other things as engineers, but the the assumption is, like, in consumer electronics, you just ship another one. And then in art, you have this kind of added complication that something is, like, an original or it's, like, has this value that's slightly outside of just the the PCB that it's printed on or the code that it's running.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Consumer electronics is you can if you can get the 5 year mark, you're doing really good. Whereas, like, art, will it work a 1000 years from now?

Cy Keener:Yeah. It's a big ask. It's a big ask. Yeah. So I think I I kinda go back and forth.

Cy Keener:I have these these kind of, like, live data pieces, and then I'll also do things. I had this large series that where we got to tag a bunch of icebergs with GPS trackers, and then I did photogrammetry or I kind of did this, like, documentation of the icebergs, and then we use that to make these things that we called iceberg portraits. So it was it was trying to really kind of show, like, with this one drawing, we could show the scale of the iceberg. We could show the path that it took, through a bay bay in Greenland, and we could, we even kinda spied on it with satellites, and we could show how it changed over time and how the iceberg should, like, change shape. So it's really just trying to kind of, like, tell this full story of the of the iceberg as it's, moving through time and space.

Cy Keener:So I think that those are, yeah, those are it's a good gamut of of examples of different projects that I've done on the art side.

Stephen Kraig:I guess I guess one other quick thing, in terms of abstracting the data and how you present it to the, someone in the gallery or someone looking at your piece, do you prefer to, get get their eyes on, I guess, on the as close to the raw data as possible or do you try to put something in between, the data and what they're looking at?

Cy Keener:Yeah. It's a really great question, and I think my my answer we it's kinda like the enclosure question where it remains aspirational. But I think, in art, it should it should if the piece is successful, it will grab you the first time that you see it and that you are curious about it and you wanna know more about it. And then if the art is good, then the more you know about it, the more that you like it, basically. Like, the more that it reveals about the kind of thought that went into it or the difficulty of the things that the artist went through to create it.

Cy Keener:And so I think, I think another another angle or just kinda side to the question you're asking is just how much are you like, there's this word didactic, which is kind of a weird word. But it's just sort of, like, how much are you kind of trying to put the information like, be very clear about what the information is, which is how much are you trying to, like, let the audience sort of experience it and know that there's something there, but also kinda create their own experience. So it's almost like in a like in a rock and roll song or something where you like, sometimes it's good when you find out what the what the artist actually meant, but sometimes you're like, oh, that that kinda ruined that song for me. So I think that the, I think that good art should sort of stand on its own even if you don't, if you don't know exactly what it's about. But that then the kind of the more you learn, then the more it's sort of like a puzzle that's sort of unfolding, and and you're kind of the more you learn about it, then the more kind of interested in you are.

Cy Keener:So that's that's what I'm aiming for. I think that that's, you know, the thing like, if you put pretty lights or, like, moving lights in a room, like, it it's kind of fun and kind of exciting, but I also want it to be something where they the person comes away with with some sort of some sort of meaning. I guess, like in art, we kind of shoot for some sort of meaning. Like, it's not any that's one of the things that sort of differentiates it from other endeavors where where you ideally, you would come away sort of seeing your world just a little bit differently, than when you saw that previous thing. You'd think, oh, like, I never really thought about icebergs and how they would actually, like, move through space and roll and change shape and do all this stuff, or I never really thought about that the ice on the Arctic Ocean could be 6 feet thick.

Cy Keener:And then if I can stand next to that, then, that's kind of a powerful experience.

Parker Dillmann:So Do we want to wrap up? I think so. Cool. Cool. So Sai, thank you so much for sharing your journey so far and your projects and and your art.

Parker Dillmann:Where can people find more about your art installations and what you're currently working on?

Cy Keener:Yeah. I maintain a a portfolio website. It's it's what we call it. It's just my full name.com. So cykeener.com.

Cy Keener:I'm sure you guys can throw a link to that. Yeah. And then I guess my my information is fairly public. I'm a a professor at the University of Maryland, so my my information is just kinda out there. If feel free to shoot an email or reach out with any questions.

Cy Keener:Yeah. But I I post some video and a lot of images on that portfolio website. So, it'd be a fun fun thing to check out after the podcast.

Parker Dillmann:Again, thank you so much, Sai. It's been a it's been very interesting getting your perspective on on, especially that podcast to get the experience. So

Cy Keener:Yeah. I've been I've been lucky to be able to do that, but I I think it's because of our Arduino community and and your company and and other folks that, have been super generous with just, sharing information and helping make that possible. So yeah. So thanks for having me on. Appreciate it.

Parker Dillmann:For listening to circuit break from MacroFab, we are your hosts, Parker Dillman.

Stephen Kraig:And Steve and Craig. Later, everyone. Take it easy.

Parker Dillmann:Breaker for downloading our podcast. Tell your friends and coworkers about circuit break podcast from Macrofab. If you have a cool idea, project, or topic you want us to discuss, let Steven and I and the community of Breakers know. Our community where you can find personal projects, discussions about the podcast, engineering topics, and news is located atform.macrofab.com.