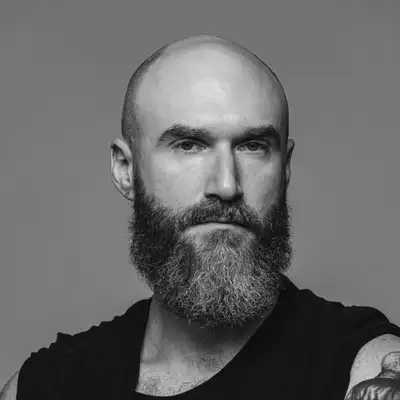

Creators and Guests

What is Private Life?

Private Life is a new podcast from The New York Review, hosted by contributor Jarrett Earnest. Each episode offers intimate, in-depth conversations with distinguished voices from across the literary landscape—about their lives, their work, and the ideas that shape both. Along the way, they revisit pieces from the Review's robust sixty-year archive (regularly releasing newly recorded audio versions of these classic texts) to situate arguments within contemporary culture. The show also includes discussions of titles from our book publishing arm, New York Review Books, featuring talks with translator Mark Polizzotti on Andre Breton's surrealist masterpiece Nadja and musician Richard Hell on the re-issue of his novel Godlike. Other early episodes find Joyce Carol Oates ruminating on true crime, while Darryl Pinckney opens up about the perils of memoir and his formative friendship with essayist Elizabeth Hardwick.

Private Life is a personable, expansive invitation for longtime subscribers and a new generation of readers alike to connect with the past, present and future of The New York Review.

Emily Greenhouse: I'm Emily Greenhouse, the editor of the New York Review of Books. And this is Private Life, hosted by Jarrett Earnest, our podcast in which we dive into the story behind the printed story, the personal history behind the intellectual history. We hope you enjoy listening.

Jarrett Earnest: This is Private Life, a New York Review podcast. I'm your host, Jarrett Earnest, and today I'm speaking with Daryll Pinckney. Daryll Pinckney is a novelist and longtime contributor to the New York Review of Books. Among other things, he's written a memoir called Come Back in September about his relationship with the critic Elizabeth Hardwick. Pinckney met her as a student at Columbia in 1973, which is the year before the publication of Seduction and Betrayal. Her book of essays on women in literature, which originally appeared in The New York Review. Pinkney has also edited and written the introductions to the New-York stories of Elizabeth Hardwick and the Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick, both books published by NYRB Classics. There are some first names that come up in our conversation that I'd like to give you some context for. Pinckney met Hardwick or Lizzie as he calls her soon after her divorce from the poet Robert Lowell. Her best friends include Barbara Epstein, legendary co-founder and editor of The Review, and the novelist Mary McCarthy. The dear Susan we discuss, who comes up near the end of his memoir, is Susan Sontag.

Hi. Hello. One of the reasons why I'm so grateful to talk with you is because when I first thought of having these conversations, the very first thing that occurred to me was wanting to talk about Elizabeth Hardwick, who is a writer that has had such a huge influence on me and many people. And you've done such incredible work about her legacy and her work in a number of ways. And I wonder if we could start for people who don't necessarily understand the complex intertwined relationship between the Elizabeth Hardwick we think of as a critic and a writer and the history of The New York Review of Books, like how they go together.

Darryl Pinckney: Well, Elizabeth Harbrick was writing for the Partisan Review in her youth, and that was the sort of anti-Stalinist liberal magazine of the time, the late 40s, early 50s. So she came from this climate of rather serious criticism, even in the time of sort of McCarthyism. I think that it was under Robert Silvers, when he was this young editor at Harper's, that she wrote this. Now much cited piece about the decline of book reviewing in the United States. I think that was 1959. And the New York review of books began during a strike of the New York Times in 1963 when publishers had no place to advertise their books. And this was a moment in American culture when New York City was still the center of intellectual light. And you could have a national magazine just by telling the country what was going on in New York because it was the center of publishing and so much else. And also the real melting pot city of the time, more so than Chicago. And so she sort of emerged from all these contending forces as one of the founders of the New York Review with the Epstein's and her then husband Robert Lowell and Whitney Ellsworth. And they start at this. With sort of nothing, but their reputations, because they immediately got the most interesting people to write for them, and I think that was significant, especially at the time. Also, they had a certain independence of mind. So they were anti-Vietnam, but they weren't ramparts. They weren't sloganeering, they weren't ideological, they were sort of suspicious of all that. Because many of them had had their formative years in Marxism and they sort of distrusted systems. That's one of the things I think they all share.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, one of the things I think about when I think about Elizabeth Hardwick, or that one thinks about is this incredible voice, this incredible style. And she really represents a kind of critical writing in which writing an essay could be as intellectually and artistically as ambitious as any other kind of writing. And what seems to happen, and I would love your sense, is that in the New York Review of Books, she has space to really experiment formally with the essay in a number of directions and I wondered when you were putting together the collected essays how you thought about that evolution in the work even though the voice was always so strong from the beginning.

Darryl Pinckney: I think that lot of her work had certain properties or characteristics from the very beginning, whether it be her sort of early fiction or her early reviews. So something in her character was always present in what she wrote. And she had no sort of narcissism as a writer. She was too interested in literature for that. But she also had a very vivid sense of what literature was. And I think it came more and more to voice. As the expression of her personality on the page and this kind of music of her thoughts, if I can say that, style mattered to her a great deal because criticism was a conversation with the works that she cared about. She liked to write about what she was interested in, not what disappointed her. She always said that takedowns were for the young and as you got older, you were interested in something a bit more engaged sure. Reflective on what you were sort of reading. And I think also her criticism always had a strong and proud sense of herself as a reader. She wasn't pedantic or anything like that. It's remarkable how in her essays, the compression of research that goes on to just the sort of last thing, the small detail that she's picked out of everything written about the Brontes, and she sort of pulls out this small thing. I think she believed in reading, very much so, and even then understood it as a minority activity in American society. So as something that had to be protected, nurtured, and encouraged.

Jarrett Earnest: You say something so beautifully at one point in your memoir and also a version of it in an introduction where you say that her work was about honoring the literature that she loved. Yes. And I think that is such a useful thing to say about her because she has a reputation of being such a sharp critic. But in fact, that is exactly where the energy in the writing is. It's about just passionately loving the books that she's writing about.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. I mean, uh... I was looking again at Seduction and Betrayal, which were the first things I ever read by her long before I knew about A View of My Own and the work that was to come. And it's really very gripping how she's immediately thinking about the Brontes and what their characters represent of their experiences and their understanding of being a woman in these circumstances in the sort of 19th century cultural landscape of no protections and not wanting what was on offer for independent women at that time. And she sort of goes right away to what they must have been trying to get across, their intentions. And she never sort of violates the people she's thinking about. You know, everything seems very considered and respectful of who they were and what their possibilities were. She doesn't go back and add or criticize from her time. She really has a way of entering into these lives on their own terms. And I think that's part of the excitement of reading her now is sort of, you feel much closer to the text than you do with a lot of other kinds of criticisms now

Jarrett Earnest: That's also interesting, because something that occurs as a frequent target across the essays that you bring together in the collected essays is her anger at the problematics of biography and biographers in their weird psychological inferences. And one gets the sense that that really matters to her, respecting the life of the artist.

Darryl Pinckney: Over time, certainly as more people she knew became the subjects of biography and then as her own life got really entangled with the matters of biography, she got really sharp about what was going on. But in the very beginning, she thinks of biography as a door. It doesn't answer all the questions, but it should raise the right ones. And so in seduction and betrayal The occasions are rather buried, but you can tell that this was a response to Quentin Bell's wonderful biography of Virginia Woolf. I think the first review she wrote that went into Seduction and Betrayal was the biography of Zelda Fitzgerald, which at the time was a sort of big deal. She didn't think very much of it, but it gave her an occasion to think about the life of poor Zelda Fitzgerald. And it's interesting, she doesn't much like the Fitzgeralds.

Jarrett Earnest: I know. It's kind of refreshing when you read it.

Darryl Pinckney: You know, she was a real child of the 30s, and so they seemed rather excessive.

Jarrett Earnest: This comes up as a leitmotif in your memoir about your relationship with her, but she also doesn't much like Bloomsbury or Virginia Woolf.

Darryl Pinckney: No, but I think that's Englishness after everything that's happened to her. She and Mary McCarthy had a kind of resistance to Virginia Woolf as womanly writing at the time, an art novel, wasn't sufficiently full of cause and effect for their generation of women who were sort of looking for something beyond the, you know, Virginia Woolfs social landscape doesn't go beyond the drawing room. And that wasn't what, they were still interested in the women's experience, but it was a bit more American, broad. They're from that time of psychological realism and this inheritance from the great sort of 19th century. So was Virginia Woolf, she just did it differently. But you wouldn't find them writing much about Joyce either.

Jarrett Earnest: It strikes me that the question of biography, autobiography, fiction, nonfiction is all over the subject matter that Elizabeth Hardwick returns to, especially because as you edited the wonderful collection of her stories, the voice is there, but it really comes into its own in the and then its ultimate apotheosis is in sleepless nights. Which is called a novel, an autobiographical novel, but it's exactly the voice that we've come to know through the non-fiction. And indeed the protagonist is named Elizabeth. The storyline more or less conforms with the details we know of her life, although it's extremely oblique in terms of how to understand its relationship to an inner life or a character that might be Elizabeth Hardwick. And I would love to know more about that, especially as you were approaching writing your own reflection on your friendship with her and knowing her as a person.

Darryl Pinckney: I think when I met her there was a sort of conjunction of factors, one that she was newly single and that Harriet was in high school and a lot of my friends were friends of hers. So that sort of got me by in many ways. Also as a single woman and you have this little gay friend, there's a kind of social ease, so he can sort of help you out. And there's none of the problems of a guy around, that sort of thing. I was a student. I was student all my life with her, never a peer. How could I have been? It wasn't going to happen. And an eager student. I really, she was fascinating to talk to all the time. So it was a great privilege to be in her presence. I was always knew that and a lot of fun and not always easy. Because a lot of sadness could go on at the same time. I think that Sleepless Nights is very revealing of her sensibility and some real core values that she held as a person and an artist. And the chief one, I think, would be herself as an observer and what she'd learned as this poor girl who'd married well and then was sort of thrown back on herself. And returned to her young love of New York City. What was possible for a woman had changed a lot from her days as a single girl to her days as a divorcee and New York was a much more hospitable place for women of a certain protection or class or means. But I think that she was never interested in the great life or the high life. That was not her thing. She knew a lot of great figures and they interested her, but she didn't feel she could sort of write about these people at all. You know, that world was so complex and people were not simple, but her as an observer of the city and of others, the thing I find most characteristic of her is her equality of gaze with whatever she's looking at. So she's never looking down on anyone or anything. She's not particularly interested in satire either because that's usually aimed at people higher. She's always looking for the offbeat, the neglected coroner, people like her who find refuge in the city. And so she's always sort of remembering this first mission of saving yourself. And finding something else and becoming something else, and she never looked down on anyone else's dreams. Some of the most beautiful lines in Sleepless Nights have to do with the suffering of bad artists, and they suffer as much as good ones. So there's a kind of mercy going on all the time, but not at the sacrifice of her intelligence, and she's not sentimental. It's a real... Kind of philosophical balance, moral balance, that she always had in her writing. That's why she could be fierce, because she's standing on two feet.

Jarrett Earnest: Thank you for saying that. Wow, what a beautiful.

Darryl Pinckney: Well, you know what I mean

Jarrett Earnest: Yeah, I do. I know exactly what you mean, but I could never have articulated it like that. One thing I'd love to know more about is I love your memoir,

Darryl Pinckney: Oh, you�re very kind

Jarrett Earnest: Come Back in September. It's so beautifully done. And the layers of voices and time is folded in such a complicated way. And one of the things I love the most about it is it's such a sensitive portrait of a very important intergenerational friendship between artists and thinkers, which are exactly how culture happens. It's always these kind of outsized influences that go across difference of time and age. And obviously, this is a kind of memoir about the time in which you came of age in relationship to her and the New York Review of Books and becoming the writer that you are. I'm thinking about it in relationship to the editorial work that you've done, editing her collected essays and also the book of stories, that both the memoir and the essay, that kind of editorial work, I think of as really devotional, as work that is saying, I really believe in this, I want it to be, it's important to me, but it should be important to you when I'm making it available.

Darryl Pinckney: Well, firstly, let me stress that I had help. So the people who did a lot of the leg work deserve to be mentioned, if I could sort of remember all of them.

Jarrett Earnest: Go for it!

Darryl Pinckney: So there is that. And then with to a certain extent, the collective was easy because I wanted everything. So you start with everything and then you sort of eliminate what doesn't fit. And you just sort of stick to mostly the literary essays. Some of her social essays I find of equal importance and so they're there. And they always have a kind of literary flavor as well. The occasional pieces are the smaller ones. She was very fortunate. That someone did the uncollected and sort of captured those because she was very clear that no assignment was too small. You know, they always got her at full sail because she didn't know how to do anything halfway. She had no idea what that meant and wouldn't want to. And, you know, it was all sort of hard to get out of oneself. An important lesson she taught by example was sticking to it. And that was really not easy in those days of running out the door at the drop of a hat. I think back then, my generation was very aware of cultural inheritance. Modernism was still very alive, as were some of its pioneers. And it wasn't in the classroom, it was in the city. You went out and you found it. And nevermind. the world of sort of John Cage or Lucas Foss or Merce Cunningham. None of that was in the classroom either. This was in city life that you found. And often you found it through your professors who took you to the theater or told you to go see this or that. It was, you know, a real sort of exchange. They wanted to pass on everything that was available to them. And that was the excitement of New York at that time. That so much was available and within reach and you could go to it, you could just go to it. I saw Baryshnikov in 1975 and I've never got over it.

Jarrett Earnest: So what was it like to return to that time through writing to try and reconstruct it in the memoir?

Darryl Pinckney: Horrible, horrible

Jarrett Earnest: Uh, horrible? Why?

Darryl Pinckney: A large part of autobiography is disguising what a flaming fool one was.

Jarrett Earnest: I think Elizabeth Hardwick says something like that somewhere.

Darryl Pinckney: She probably did and I knew who she was talking about So there was that and I used to my diaries a lot and that was I'd never gone back and looked and that was hard

Jarrett Earnest: That was something that in the experience of reading it, there is this incredible specificity. I read this, I saw that, this happened, this was the weather. And as a reader, you think this person must have been a very dedicated diarist, but it isn't necessarily clear until the end of the book. It starts to open up and you get more direct, seemingly direct quotations of diaries.

Darryl Pinckney: Yeah, I would cut those now.

Jarrett Earnest: Really?

Darryl Pinckney: Yes.

Jarrett Earnest: Why?

Darryl Pinckney: They have the death ones. It just makes the book too long. It's meant to be this long postscript, sort of about dear Susan in Berlin, but it makes the books too long and it just sort of stopped with, the book ends with the death of everyone representing a particular group. Howard Bruckner or Sterling Brown or Virgil Thompson or Jonathan Lieberson. And then it ends with Mary McCarthy. So I should have just done that and left out the Susan stuff.

Jarrett Earnest: Although it was incredibly fascinating. I'm glad it was in.

Darryl Pinckney: You know, I don't like a lot of the stuff that's been written about Susan. She was not a fraud by any means. And we take for granted a lot of what she was the only one who knew about back then. You know she really did educate as she wrote. And talk about someone who her learning was real when she wrote about philosophy. I mean, she's working up Walter Benjamin. Like everybody else, but she knows a lot more than everybody else working him up. So that part of her was very real.

Jarrett Earnest: So you included that material as like a corrective or

Darryl Pinckney: No.

Jarrett Earnest: No?

Darryl Pinckney: just a kind of, it was sort of low centric parts. And she's talking about Lizzie and stuff like that. So I was doing their relationship, but I didn't have to have it.

Jarrett Earnest: But also it seems like it kind of shifts you out of the book because it also, at that point you're living in Berlin,

Darryl Pinckney: Yeah.

Jarrett Earnest: It's no longer a New York story.

Darryl Pinckney: No.

Jarrett Earnest: And so I kind of..

Darryl Pinckney: It's all epilogue.

Jarrett Earnest: Yeah.

Darryl Pinckney: But it's too long.

Jarrett Earnest: Well.. I felt like the camera was just like pulling back very slowly.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. Into the documents.

Jarrett Earnest: it was hard to write because you were looking back at your diaries and seeing things that happened or that you thought or said that you now have distance from, and in that sense was writing this memoir redemptive or what did it mean to return there but also to try and create a form out of it?

Darryl Pinckney: It meant 50 years had gone by, it really did. It was a shock that so much time had gone by, but I had a wonderful time revising it because then a lot of the period returns and you know, you have the structure and this and that, and you're mostly taking things out or trying to shape things or mostly leaving things out in order to shape things. I felt a great sense of gratitude looking back. I was very fortunate in the people I met and the experiences I had and what I survived because of course I didn't put in the worst.

Jarrett Earnest: There's an aspect to it in which the emergence of AIDS becomes a whole other story.

Darryl Pinckney: Changed New York.

Jarrett Earnest: And you could really feel that in the book so it stops then that's the end of the book

Darryl Pinckney: Yeah, it's really the books really stops in 81

Jarrett Earnest: Mm-hmm.

Darryl Pinckney: And then picks up again in this postscript of recovery of moving to Berlin. That was 87.

Jarrett Earnest: One of the things that's so lovely about the book is that you bring forward so much information about her writing different pieces in your friendship with her and you get background and it's very light but you talk about her writing that amazing piece that I love that's in the collected of the mistress and wives about the Russians and saying well this is partly written in the aftermath of Robert Lowell's death and then it adds this kind of coloring to that essay and what it meant for her to think that through.

Darryl Pinckney: I mean, she wouldn't have liked to have put it that way, but it's hard not to take it. Maybe it was a kind of triangle because Lowell didn't really want to let either of them go. In the same way that seduction and betrayal, the first essays are written after he's gone or after she's found out what's happening. And so, you know, it's not about her, but she is thinking about the experience of women as a way of not being a victim, really. You know, thinking her way through what she's feeling and it also reanimates the literature. Because she's not saying she's a hero, that's not it at all. But she's talking about what's changed for women. And the seduction and betrayal of the lecture ends very bleakly, really, that sex isn't in it anymore and so neither are consequences, you're kind of really abandoned.

Jarrett Earnest: I mean, when I read Seduction and Betrayal when I first moved to New York, it was electrifying in terms of what a book of criticism could do. It's almost like a perfect book, you know, the way it builds. And rereading it, what stood out to me again was the essay on Sylvia Plath is just having this incandescent because of course the story of life is so overdetermined and it's there. But she goes back into the language and into the poetry and shows you why this is a poet like no other poet.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes, or this similarity to George Herbert that always got me. That was quite something, you know, yeah. Yes, that's a sort of deep one, I think. And really speaking to the feminist concerns of the time without speaking in that jargon at all. But I think she got poor Anne Sexton's number as well, things like that. But you know what comes across most strongly is the total surprise Sylvia Plath was at the time and in poetry by women. Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop had a lot, but not that. And I think that's what Lizzie's very strong on.

Jarrett Earnest: Right, getting to feel that shock of recognition almost like in the moment, and then that

Darryl Pinckney: That violence

Jarrett Earnest: The violence of it. And also there's the way that it ends where she talks about listening to the recordings of her read those poems, and it's such an amazing description of her voice, the unlikeliness a certain voice.

Darryl Pinckney: I went to the Lilly Library after I read that essay and played those plath recordings. And it is not what you would have expected at all. She's not a young, sensitive flower at all, she's a very bold speaker.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, as an essayist, there's a number of kinds of arguments that she makes or structures that she uses, I mean, very many. One of them that is the most wonderful is almost retelling a plot. But in the retelling, because of its emphasis, concision and style, it is analysis, and it's thrilling. And then it leads you to all these recognitions aboutit.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. Because she's going on largely about motive. So she's speaking to the writer about what was going on here. Again, in seduction and betrayal, especially in American tragedy. You can imagine her coming in from seeing the revival of The Doll's House and really thinking, you know, something's not right here and going through it. But you now, as she's sort of reviewing, she's really getting at what these characters are like and what's in them and not in them. She's fascinated and on head a gobbler completely, but just because she's thinking about them as sort of motive and psychology. One of the essays she never got around to writing was the difference between motive and murder in literature and motive and murdered in these real trials. And she couldn't get past the problem that in real life they can't articulate what they were going to do or what they're thinking. And, of course, in literature, all you get is motive, in a way, in some things. But she had a real ability to penetrate to what was going on in character and how it related to action and or not, especially or not. And the essays on Ibsen's women I find fascinating because they come just at that moment when the Ibsen is being done again. Especially in this kind of Bergman, Liv Ulman way. Her essay was before that revival, but it still comes from that season of revival of Ibsen as this writer on women and women actresses wanting to play these rather mysterious figures, some of them rather opaque.

Jarrett Earnest: I know it's almost an impossible question, so let's go ahead and ask it. What essays have you returned to the most over the years for various reasons?

Darryl Pinckney: That's hard to say. I think Billy Budd, certainly anything on Melville.

Jarrett Earnest: She was so special. Those essays are very special. What do you think that is?

Darryl Pinckney: She loved crazy language and that was Melville. She loved Dickens for that reason, you know for her he was like really wild guy

Jarrett Earnest: Sort of the best one. But she never wrote on Dickens, did she?

Darryl Pinckney: Not really, not really. I like her on Edmund Wilson because for her he was the origins of the kind of reviewing that the papers were doing, you know, for a general reader who knew something or wanted to know something. I'm less interested in him than I used to be. So I'll just stick with the Melville for the moment.

Jarrett Earnest: And of course, it's her best friend's ex-husband.

Darryl Pinckney: Right.

Jarrett Earnest: So there's also that thing about biography and autobiography.

Darryl Pinckney: You know, I think privately she felt that Mary married Edmund Wilson because she didn't have the nerve to marry Philip Roth, Jewish guy, rather out of it. And so she sort of chose this older teacher, really, who famously, or so they said, locked her up and made her write. I'm fascinated that they don't really read Mary's stories, young women. Do they?

Jarrett Earnest: I'm the wrong one to ask. But it is reading her essays makes you understand why Mary McCarthy was such an important figure at the moment in which her fiction was appearing.

Darryl Pinckney: Also, I think her writing on Vietnam is sort of unrecognized and it was really quite something, those trips to Hanoi that Bob sent her to. She didn't sort of fall for all of that. I thought that she's really rather good. And I think that Memoirs of a Catholic Girlhood was Lizzie's favorite by Mary. She was rather mean about her fiction, even to her, I won't say to her face, but in her time. She's rather hard on conventional fiction.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, that's one of the things that's great about your book is you get a kind of sense of the very complicated situation that she and their group of friends were in between wanting to support the people that they love and admire and also maybe thinking I don't think this is a great book and how do we deal with that?

Darryl Pinckney: They didn't have any trouble dealing with it, they just said so. There was a lot of sort of in vino veritas running around in those days, I think.

Jarrett Earnest: Do you think it has to do with the way you were talking about the psychology of motive that made her so particularly attuned to late 19th century novels? I'm thinking of Henry James and Melville in particular as being such important, I mean, vehicles for her thought. The writing about them and Edith Wharton are sort of on a different level.

Darryl Pinckney: I think Edith Wharton she was interested in her social observations and her life as a sort of woman. Henry James certainly interested her as this writer of prose and someone from New England she could bear and then I think the novels rather fascinated her as works in themselves. Melville again is a different order you know I think that stirred something in her soul this terrific loser.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, I mean, starting with the essay on Bartleby the Scribner, which is incredible, but I found the later piece on Melville in love to be just so moving.

Darryl Pinckney: Also, she sort of identifies Hester Prynne as a forerunner or Bartleby in a way. She doesn't want to explain herself either. So these people who are somehow inviolable, I think attracted her in fiction. The mixed character, you know, I think that they interested her more than people who illustrated a certain point. I think she appreciated the complexity of consciousness that Melville couldn't help but write about in a way. Yes, an experience. What it meant. And just sort of stumbling onto this symbol and using it, but not not mucking it up.

Jarrett Earnest: When you described Edith Wharton as somebody from like a northeastern writer that she could bear there, she has such a complicated relationship to being from the south. And that's something you get, I mean, comes up in her own writing in different, different ways, but also that you sort of move around in your memoir. And I wonder if you could speak a little bit to that. I think that's her period.

Darryl Pinckney: So she liked Faulkner, but Erskine Caldwell would have belonged to an earlier time. I don't particularly remember her that interested in Carson McCullers and that sort of Gothic writing at all. The only Southern writer she sort of dealt with was Faulkner. She liked Walker Percy, you know, and stuff like that. And oh, she did like Flannery O'Connor very much, very much. Well that was also a weird one.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, also think about the losers.

Darryl Pinckney: You couldn't get any weirder.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, I also think that there's a kind of touching thing that you describe about her friendship or her kind of fondness of Katherine Ann Porter.

Darryl Pinckney: Right.

Jarrett Earnest: As almost like a self-made mess.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes, I think that was exactly it and she did like a lot of the stories which surprised me you know they've never been my thing but she did but I think it was Katherine Anne herself who really appealed to Lizzie because she was you know completely mischievous.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, you have an anecdote in your memoir where they're having lunch or dinner with Alice B. Toklas and Katherine Porter nudges her and says, if I looked like that, I'd kill myself.

Darryl Pinckney: Yeah.

Jarrett Earnest: I mean that's kind of all you need to know to be like, this is someone that you want to have at the party.

Darryl Pinckney: Yeah, yeah, that was true. She did say that. That was funny.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, one thing I also was so struck by, I love the later essay on Gertrude Stein and speaking of Alice B. Toklas and the thing I wanted to just pull apart out of it because it seems so indicative of the way that her writing is just allows you to think something new about something you know very deeply. And so this piece on Stein, she says, such was her gift. She talks about Stein as a comedian. One gift never boils away, she is a comedian. Such was her gift and she created a style to display the comedy by a deft repetition of word and phrase. To display the the comedy of what? Of living? Of thinking? The comedy of writing words down on the page? Perhaps most of all. She was not concerned with creating the structure of classical comedy, the examination of folly. What she understands is inadventure and incongruity. Imperturbability is her mood. And in that, she is herself a considerable comic actor in the line of Buster Keaton. So just one paragraph, you have a whole new way to think about Stein.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes, that's true. I'd forgotten that, I really had, and that's actually rather brilliant because she is funny, but we forget to say so. We're so busy looking for the meaning of this code or trying to unravel the rules of her sort of language. Yeah, yeah, that's very funny. I don't think it's something that comes up even in this rather new and good book by Francesca Wade on, on, you know, Gertrude Stein doesn't come across as a comic figure anymore.

Jarrett Earnest: Yeah. She's not slapstick, but here we've got her being Buster Keaton.

Darryl Pinckney: Yeah. And you can, you can feel that much more, but you know this is the thing, comedy dates as fast as the erotic in culture, you know, I wonder how Charlie Chaplin is full of pathos. But not humor to me. And well Buster Keaton's still funny. Yes, it's wonderful way to look at Gertrude Stein, who is impenetrable otherwise. This rather gets one off the hook.

Jarrett Earnest: Totally, and lets you enjoy it.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. And also, you cannot read Gertrude Stein twice. You have to read it when you're young. The autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is, Lizzie always said, that's the one you can stand. You know, wars I've seen in America, they're really not so easy to get through. And once you have the shorter things Lizzie's talking about, like Tinder buttons and things like that.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, so if you'll indulge me, she gets us to Buster Keaton, but then the very next paragraph, we go somewhere even more surprising. Remarks are not literature, so she said, but the remark is her triumph. She lives by the epigram and bits of wit cut out of these stretches or repetitions as if by a knife and mounted in our memory. Her rival in this mastery is Oscar Wilde, with whom she shared many modes of performance. The bold stare that face down ridicule, a certain ostentation of type, the love of publicity, and the iron to endure it. And then continues extending this relationship of thinking about Stein in relationship to Wilde, which is completely brilliant. Who expected it?

Darryl Pinckney: Yeah, I'd forgotten that completely. Because you think he's such a dandy and you think she's so butch, you don't put them together. But actually everything she said was true, especially the ability to endure it. That was really, that's quite something.

Jarrett Earnest: And the other thing that happens that she doesn't even have to put too much pressure on is that then you start thinking about these two characters and their queerness and their relationship to language in their own sexual difference and performance and then it opens into something quite profound.

Darryl Pinckney: And they're both, now we know more than Lizzie did, how sexual their writings are, especially Gertrude's, which she wouldn't have been so drawn to, I would say, to read them that way/

Jarrett Earnest: She is a writer, and as the collected essays attest, she's a writer who wrote at a very high level about a wide variety of things over decades. And the collected essay is organized chronologically. And I'm wondering what your sense of also having known her from when you met to the end of her life. How her subjects changed or if there was an aspect of the essays that sort of started to get more attention than they had at other periods.

Darryl Pinckney: I think the language changes somewhat and maybe darkens a bit as time goes by, but also I think becomes a bit more forgiving and calms down some. In her most sort of intense period, you know, things fire at you one thing after the other and she takes more time to prepare her points sort of later on because she's reading in a different spirit, almost. You know, she's sort of recapitulating or looking for what she may have not seen before. They have a sort of broader phrase or broader stroke and they move at a different speed. They don't have that sort of bombardment in some of the earlier ones where she's firing on all syllables all the time. You know, they sort of, I think, have a bit more distance.

Jarrett Earnest: The last thing I want to ask you is just, what do you think one might think about her today? Like young writers, artists, thinkers, when they go back to this incredible body of work, where do you it fits in our present moment or what could it open?

Darryl Pinckney: t I think that people should pay attention to what she read and not only that she read. I know that people want to widen the canon or expand the literatures that are available and maybe for some she was very narrow in her tastes. You don't get her, she read the South American writers but she didn't write about them. But she loved Carpentier, things like that. She loved the East Europeans but she really write about them very much, you know, she... Very drawn to experiment, new voices, things like that, but she certainly respected the European classics as the source of tradition and she was a very big believer like musicians or artists in sort of mastering the basics in order to wring your own changes with the authority that you need it. And so I think that people should pay attention to what she read and that she wasn't afraid to read anything. She really was not afraid of any book and she wasn't afraid to be not up to it. You know, some things weren't for her. She was not shy about, you know, I couldn't do analytic philosophy with Susan and Mary and Hannah. I just, I'm not gonna do that. She didn't sort of like the abstract in particular. Was always concrete. And I think that was her closeness to poetry, that it was concrete. She was very big on true images and not sort of flighty poetry nonsense. She really disliked that more than anything, that sort of pretension and false poeticism. You know, literature was concrete

Jarrett Earnest: Well, also the way you talk about poetry being concrete, you have understanding in her writing that language is concrete, it's material. And she was very interested in its physical properties.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. It communicated in many ways. You know, language functioned on a lot of levels and she was very alive to the undertones and overtones of words and phrases and sentences. She had a great kind of sense of rhythm and musicality and none of it came from the church. You know, she's not any of that kind of thing at all. She's so far from the sermon that's not her. None of it. She really is just the gift of having this ear, this rather flawless ear, and a sort of also a gift for the apt. Every image is convincing. Every comparison opens a new door. There's the leaps she made. I remember Mr. Silvers used to say... It's not only in her language, it's in the leap of thought that she could make that she's most like a poet.

Jarrett Earnest: In the move that we just pulled out of the essay on Gertrude Stein to go from Buster Keaton to Oscar Wilde, any either of those would have been a brilliant thing to get to in an essay, but to go to one to the other is a higher level.

Darryl Pinckney: And to have us still understand them.

Jarrett Earnest: Effortless.

Darryl Pinckney: Well, no.

Jarrett Earnest: They come off as effortless. That's why it's good writing. That's the whole point. But I guess you're when you said no that meant that because she worked very hard at it.

Darryl Pinckney: Well, you know, everyone always says that she worked very hard at sort of structure and putting things together, but again, the sound is living within her all the time. You know, she is herself, no matter what she's writing, a letter, a laundry list, you now, the sounds is her. She's like a kind of great singer.

Jarrett Earnest: . But that's just a gift. That's just something you have.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. It really is. It really has. Poor Susan knew what it sounded like in labor to get there, but it's not the same thing. You know, Lizzie had to tame hers and to sort of learn to use it because she had it in such force, not abundance, but such force. She almost wrote because of the overpowering experience of reading. And she was the fastest reader I'd ever met. And she didn't skip words. I promise you. How she did that, I don't know. But she really loved to read.

Jarrett Earnest: I think there's a beautiful moment in your memoir that I have had this feeling so many times where she's just finished reading some big classic and you see her and she says, something to the effect, isn't it incredible we get to do this? You get to read.

Darryl Pinckney: She was that. She was, yeah. You know, to talk about her makes me feel happy because, yeah, it was a very important experience. Made me a writer. Or convinced me that I could be. And she was a really electric and generous and beautiful soul. She really was. And she very open to the young and she wasn't fake ever. Not ever. She couldn't be. That was her real weakness. She could not fake it.

Jarrett Earnest: Well, I want to thank you for the ways that you've made that available to other people through your editorial work, through your memoir and through this conversation.

Darryl Pinckney: You're very kind. Thank you very much for giving me the chance to remember this very striking writer

Jarrett Earnest: This podcast is available across listening platforms. You can go deeper into these conversations with a subscription to the New York Review of Books, which, in addition to 20 issues a year, gives access to the full archives since 1963, searchable on our website. Subscribe at a discount today at nybooks.com slash pl sub. That's n-y-b-o-o-k-s.com slash p-l-s-u-b. You can buy your own copies of Elizabeth Hardwick's books, including Seduction and Betrayal, Sleepless Nights, both the collected and uncollected essays, and her New York stories at NYRB.com and at your favorite booksellers. Private Life is hosted and produced by me, Jarrett Earnest, along with associate producer Luna Hayes-Dean. The audio is edited and produced Tyler Hill. The music is by Matthew O'Coyne, and it is a production of the New York Review.