- How the hosts and guests chose engineering as a career.

- The impact of their first jobs out of school.

- Good and bad reasons to change jobs.

- The role of mentorship and learning from senior engineers.

- Reflections on imposter syndrome and its effects.

- The importance of prioritizing tasks and learning to say no.

- Career transitions and the challenges faced.

- The influence of non-engineering jobs on their engineering careers.

- Advice on surrounding oneself with smart engineers.

- Experiences of working in different engineering roles and industries.

- The significance of having a plan and being open to change.

- The role of personality in learning from colleagues.

- Predictions and aspirations for the next five years.

- Thoughts on the evolving nature of electronics and engineering careers.

- What are your thoughts on changing jobs for career growth?

- How do you handle imposter syndrome in your engineering career?

- What non-engineering job have you had that influenced your engineering career the most?

- Where do you see your engineering career in the next five years?

Creators and Guests

What is Circuit Break - A MacroFab Podcast?

Dive into the electrifying world of electrical engineering with Circuit Break, a MacroFab podcast hosted by Parker Dillmann and Stephen Kraig. This dynamic duo, armed with practical experience and a palpable passion for tech, explores the latest innovations, industry news, and practical challenges in the field. From DIY project hurdles to deep dives with industry experts, Parker and Stephen's real-world insights provide an engaging learning experience that bridges theory and practice for engineers at any stage of their career.

Whether you're a student eager to grasp what the job market seeks, or an engineer keen to stay ahead in the fast-paced tech world, Circuit Break is your go-to. The hosts, alongside a vibrant community of engineers, makers, and leaders, dissect product evolutions, demystify the journey of tech from lab to market, and reverse engineer the processes behind groundbreaking advancements. Their candid discussions not only enlighten but also inspire listeners to explore the limitless possibilities within electrical engineering.

Presented by MacroFab, a leader in electronics manufacturing services, Circuit Break connects listeners directly to the forefront of PCB design, assembly, and innovation. MacroFab's platform exemplifies the seamless integration of design and manufacturing, catering to a broad audience from hobbyists to professionals.

About the hosts: Parker, an expert in Embedded System Design and DSP, and Stephen, an aficionado of audio electronics and brewing tech, bring a wealth of knowledge and a unique perspective to the show. Their backgrounds in engineering and hands-on projects make each episode a blend of expertise, enthusiasm, and practical advice.

Join the conversation and community at our online engineering forum, where we delve deeper into each episode's content, gather your feedback, and explore the topics you're curious about. Subscribe to Circuit Break on your favorite podcast platform and become part of our journey through the fascinating world of electrical engineering.

Welcome to circuit break from MacroFab, a weekly podcast about all things engineering, DIY projects, manufacturing, industry news, and career reflections. We're your hosts, electrical engineers, Parker Dillmann. And Stephen Kraig. This episode is 435, and we have 2 special guests this week. We have Chris Gammell and James Lewis.

Chris Gammell:Am I supposed to say

Parker Dillmann:yo there? Say whatever you want.

Chris Gammell:James, you're you're supposed to say yo. Yo. Yep. Always drool. Always.

Parker Dillmann:So we're gonna be cross posting this to the amp hour podcast, which Chris Gammel is part of. So we're gonna kinda just do Part of.

Chris Gammell:All of. All of? Come on. I have the heart and soul, Parker.

Parker Dillmann:We're gonna do, introductions for everyone including ourselves. Steven, do you wanna go first?

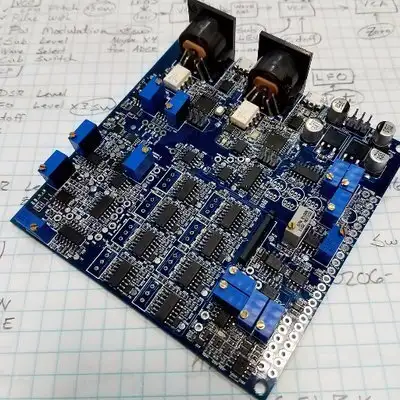

Stephen Kraig:Sure. I am Steven Craig. I am cohost of the Circuit Break podcast and a component engineer in the aerospace industry. My background includes oil and gas sensor design, contract manufacturing, audio electronic repair, and synthesizer design.

Parker Dillmann:I am Parker Dohman, cofounder and lead electrical designer here at MacroFab, a company changing the PCB manufacturing process with transparent pricing and efficient production solutions. I have a background in embedded system design and digital signal processing, and I've been in the manufacturing industry for over 10 years now. And y'all y'all fight on which one goes next.

Chris Gammell:James, you go you go you go ahead.

James Lewis:Yo. My name is James Lewis, and I'm a freelance content creator for Bald Engineer Media. You might know me from my YouTube channel, ad ohms, or as a video host on element 14 presents, or maybe from some of the product and project write ups I do over on hackster.i0 news.

Chris Gammell:Great. Your turn, Chris. Okay. Thanks, James. Yo.

Chris Gammell:Thanks, yo. I am the host of the amp hour podcast, 14 years running, and I'm developer relations lead at Goliath. We're an IoT SaaS startup that, connects stuff to the Internet. And I get to build hardware that has things like Bluetooth and cellular and WiFi and Ethernet and everything else. And I use a lot of Zephyr real time operating system, which I I love and I love talking about.

Chris Gammell:Thanks for having us, guys.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Thanks for coming on. Yeah. Yo. Sorry.

Parker Dillmann:So we're gonna have a episode this is kinda gonna be unusual because because when we talk about engineering career paths, which is something we we and actually just engineers in general just don't really like to talk about. We have 4 engineers that also probably don't like to talk about that kind of stuff, but we're gonna do it anyways.

Chris Gammell:Who is the target audience for this then, Parker? Is it like yeah. The young ones? Is it young pups than who we're trying to talk to? Or are they more like the advanced engineers that are looking to be retrospective about their careers?

Parker Dillmann:You know, I should know what our target audience is with this podcast. It's whoever downloads this this

Stephen Kraig:silly thing.

Chris Gammell:Whoever's fastest on the donate button, click now.

Stephen Kraig:The So I think

James Lewis:I think if we you know, I think it'd be easy to say for college new new college hires or people going to school or maybe people that are midway through their careers. But I think if we kinda step back, you can almost say, at some point, everybody has thought, at least, where am I at my career, and am I going in a in a good direction? Mhmm. And, you know, while I I don't like to ever say this can target everybody, I think there's a way that our audience could target everybody.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. I mean, probably not like someone who doesn't care about electronics. They're probably still in the electronics sphere. So they're they're, like, coming here for, like, generic career advice. They're probably gonna be underwhelmed, you know.

Stephen Kraig:But but

James Lewis:I I I don't think they'll be coming back if that's the case. Yeah.

Chris Gammell:That's right. Yes.

Stephen Kraig:But but but okay. The 4 of us all kind of landed in engineering entertainment. Obviously, we're all here. Right?

Chris Gammell:Are you not entertained?

Stephen Kraig:Would you would you say that any of the 4 of us have had a generic career or a standard career. I I would argue absolutely not.

Chris Gammell:I I don't know if that exists any what is the standard? I yeah. I don't know. Like Well, I think

Stephen Kraig:the standard

Chris Gammell:is your your your picture of the standard engineer.

Stephen Kraig:I I guess I I guess it goes back to, you know, being younger and talking to my father about the the workplace, and it was go to school, get your degree, get a a job right out of school, and do your damnedest to stay there for 30 something years. Save all your money that you can you can and then retire. Right? And that's I guess, that's more of the air quotes generic.

Parker Dillmann:Is that the best standard for an engineer then?

Stephen Kraig:I don't know. I've never I I I have yet

Chris Gammell:to make an engineer who this standard peanut butter sandwich. Right?

Parker Dillmann:Right. Right. Right. Yeah. Actually, that's funny to think about because that's I mean, my dad didn't have what would we call a cons a a standard because he wasn't a chemical engineer, but then he moved over to business.

Parker Dillmann:And so he kinda transitioned out of a standard engineering role.

Chris Gammell:Wait. Do you all have parental figures that were engineers?

Parker Dillmann:My dad was an engineer. Yeah?

Stephen Kraig:My father was a geophysicist.

Parker Dillmann:Wow. Yeah.

James Lewis:Yeah. I my my parental figures were not, but there were members of my family that were engineers.

Chris Gammell:Wow. That's great. Sales. I come from the sales sales family. My dad and my my grandfather were salesmen.

Chris Gammell:And I knew what I didn't wanna do with sales because my dad was traveling 3 to 4 days a week for my entire childhood. Great dad. Don't don't get me wrong. Wonderful. Wonderful dad.

Chris Gammell:He just traveled a lot. So I know I didn't wanna do that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So that that actually leans right into the first first question we got here is, how did we pick engineering to study? Why? Kinda like some background there.

James Lewis:I think the easy answer was you didn't have to spell very good. And so that worked out well for me.

Stephen Kraig:Fully, honestly, you don't have to write as many papers. And that was a motivating factor. One of the motivating factors.

Chris Gammell:Really? Interesting. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:No. Honestly, it was I I got into electronics in in high school, and and it was one of those things where I enjoyed it enough where I was like, what can you do with this? And then realize that there's entire fields that are devoted to it. So I was like, I will do that.

James Lewis:Yeah. I actually have a really similar I started in high school. I took a class, I think it was my sophomore year. The title of the class was, communication technology. And what's interesting about it is it covered all different types of ways that humanity communicates.

James Lewis:We had a little bit of photography. We did some screen printing on t shirt t shirts to to, talk about advertising. And then we had these little heat kits that, we had set up, LEDs to basically show that you could communicate by making, lights flash. And then there was supposed to be an electronics component to that, but nobody else in the class cared at all about the electronics, but I did. And so that was as soon as I started playing with that thing, I knew what I wanted to do.

Parker Dillmann:No. I was always building stuff as a kid, helping my dad, like, fix cars and and all that stuff. And my dad was an engineer, and I was like, you know what? If if being an engineer lets me keep doing that kind of stuff, then that's what I was gonna be. And I was a I actually went to school originally to be a petroleum engineer, and then I actually I I started meeting people like Steven's dad was geo geophysicist in, like, sedimentary rock classes.

Parker Dillmann:And I was like, I I I'm not that excited for rocks. I can't do this. And I was I was at the time, I I had just made my first printed circuit board as a side project. I'm like, you know, what about electrical engineering? And then I was the only person that transferred into the EE college that semester.

Stephen Kraig:I was too.

Parker Dillmann:So Have

Chris Gammell:you guys known each other that long?

Stephen Kraig:No. No. No. We met in 2015 when I Yeah. Knocked on Macra Fab's door, and I was like, I want a job.

Stephen Kraig:But you

Parker Dillmann:can't you can't even get boards made.

Chris Gammell:Parker said Parker said Stevens You said like Stevens. I think I thought you meant you were actually learning from Stevens' dad.

Parker Dillmann:No. No. No. No.

Chris Gammell:No. No. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Like Stevens' dad. That geophys that class was eye opening. That's way better. It was eye opening on, like that was the first time I was ever with other people that were so excited about something I didn't care about. Which okay.

Stephen Kraig:By the way, my my father still has rock collections that he brings out every once in a while just to look at. And every time he has visited up here in Colorado, I will come home from work or wherever, and I will find random rocks on my front porch that he just went and found on a walk. And he's, I'm just gonna I'm gonna bring him home with me. Okay, dad? Cool.

Chris Gammell:They they followed me home. I swear.

James Lewis:That's awesome. Do you let him keep keep them?

Stephen Kraig:Oh, absolutely. Yeah.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. His luggage his luggage on the way home is, probably pretty heavy.

Stephen Kraig:And and and and he'll just be like, yeah. They were cool. I wanted them. Okay, dad.

Chris Gammell:That's great. That's great. Yeah. You know, for I always felt a bit, self conscious, you know, like so on the amp hour, we'd have people who are like, yeah. I was like, doing electronics, you know, since I you know, Dave, my co host, of course, has, you know, been doing electronics since he was like 8.

Chris Gammell:And I'm like, I I didn't know what I wanted to do. I just kinda I took a shot, honestly. Like, I knew I like physics. We did some physics in high school and then I don't and then I like had some old walkie talkies I took apart and that was basically like the guess that I took and it it honestly, it didn't work out that well in college. I was much more interested in a beer and, you know, talking talking to ladies.

Chris Gammell:And and and it was until, like, much later in my career that I actually, like, kinda came back into it and started focusing and and enjoying it. Yeah. I don't know. I just feel like if someone is listening who's a college student, you're probably not listening if you're not interested in electronics. Right?

Chris Gammell:But if you were listening and you're an electronics student and you're like, oh, I don't know. Sometimes it just doesn't hit at the beginning, you know. I don't know. I could it didn't hit for me. I got through it, of course.

Chris Gammell:I let I, you know, I I was okay at it, but I didn't really get into it much later until much later.

Parker Dillmann:It it's interesting hearing you say that because it earlier on in my career, I kinda got, like, FOMO because I was kinda jealous at people who were into electronics sooner than I was. Does that make sense?

Chris Gammell:Totally. Yeah. Same.

James Lewis:But but why okay. I'm curious why why you would feel that way. What what was it that you feel like you were missing out on?

Parker Dillmann:The experience and just up with that kind of stuff. It's the same thing with oh, not not in just engineering, but, oh, I I had it on when when Chris was talking. I I can't remember what that point was anymore.

Chris Gammell:I'll start talking again. I mean, for me, it's yeah. I look at kids now, and I'm like, you know, so I watch, you know, Mark Rober's videos, and I see, like, the the kits that he puts out. Oh, the, you know, the KiwiCo and all the kits that are out there. The sponsors this episode is not sponsored by any of them.

Chris Gammell:But, you know, just like the resources that are there, I'm like, oh, my god. I wish it would I don't know if that actually would've hit with me. Like, when I was a kid, I was interested in sports and like other, you know, and like other traditional, you know, like, Thundercats and, you know, the good stuff in life, guys. Power Rangers. And yeah.

Chris Gammell:So I don't know if it would hit now, but I look at it and I'm like, yeah. I wish I I think in I think what Parker's saying is in is the thing that inspired me was, like, I just wish I would have kind of this thing I know that I actually like now, I wish I would have liked it then because Exactly. More time would have been better. You know?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I I feel the same way with all the automotive stuff that I do too because I didn't get Yeah. You know, I've always worked on my dad's cars and stuff, but I didn't really get into working as a hobby, I guess, until after college. And I see, you know, people these days that are, like, 16, 17 doing that kind of stuff. And I'm, like, it feels like I have to go and catch up.

Parker Dillmann:Is that and also a good good explanation to you? It feels I'm like Yeah. I have to go harder at my hobbies just to feel like I am trying to catch up with these people. Yeah. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Okay.

Chris Gammell:I know

Parker Dillmann:that's not the right mentality, but that's what it feels like. I said that was that was earlier on. I've I've Yeah. Yeah. I've come to reckon with age effects hits everyone.

Parker Dillmann:Was the the the best time to start was yesterday, but the second best time is now.

James Lewis:So So, Parker, now I'm now I'm starting to be able to relate to what you and Chris were saying, but for me, it wasn't during school when I started studying electronics. It was immediately after I got out of school, and I was surrounded by people that had 20 years of experience. And, I felt like, on day 1 of my job out of school, I was like, holy cow, I have got to get caught up with everything else that's going on. And and I think what you're describing is that is that they would everybody I worked with would talk about how things over the last 5 10 years had had culminated into a certain product or decision somebody made. And I just felt so out of place because I didn't have any of that context.

James Lewis:But for me, that didn't happen until I got out of school.

Stephen Kraig:You know, I've I've had actually something it's funny. It's it's similar to that, but in the opposite direction. We at work, we just had an intern start the other day. And hearing this this I'm gonna say kid talk who, about intelligently about electronic stuff, sure, I can keep up with his conversation because I've got 14, 15 years on him. But I look at this kid, I'm like, you are so far ahead of where I was when I was your age.

Stephen Kraig:I am almost having FOMO of you. I

Chris Gammell:yeah. I think that is actually the same thing. I think that is the same thing of, you know, seeing the Utes the Utes and how far ahead advanced there. But, you know, yeah. It's it's great.

Chris Gammell:It's good for them, I think. No. I

Stephen Kraig:think yeah. It's really good.

Parker Dillmann:That might also just be a personality trait of what was it called? It's not FOMO. It's the imposter syndrome. It's kinda it's related to that.

Stephen Kraig:Are you saying the intern's an imposter?

Parker Dillmann:No. No. No. You you yourself

Stephen Kraig:part part

Parker Dillmann:of You

Chris Gammell:are the imposter.

Parker Dillmann:Part of these feelings are kinda like imposter syndrome, meaning that you're not good enough to be doing the the jaw. I'll I'll post it anyway. Anyone listen everyone gets that.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. I hope because I do.

Chris Gammell:I Yes. Totally.

James Lewis:If I ever get to a point where I don't suffer from it, I'll let somebody know.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I I think that's actually one of the, reasons why we even go into engineering. I do think our mind is is wired in that way where not knowing something or not feeling comfortable with something or not being capable can drive us insane. Right? And and so, that relentless pursuit of knowledge or capability is part of being an engineer or at least some portion of it? Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Actually, you

James Lewis:know what, Steven? Now, if I think if I think about it, you know, we all kind of said we had this moment where we had this fear that we've missed out on something, and none of us said we were afraid to get caught up. It was the feeling that we had to get caught up. Whether that was true or not, that's debatable. Probably not.

James Lewis:But isn't it interesting that we all saw that as a challenge and took it on instead of said, oh, clearly, this isn't for me because I'm not as experienced as everybody around me or or as into this stuff as everybody around me.

Stephen Kraig:Do do you guys ever go into work and and just look around and be like, oh, my God. Everyone is smarter than me. Like, everyone is 50 times smarter me. Is that just me? It's just me.

Stephen Kraig:You know

James Lewis:what's funny? And and I'm I'm really not trying to be conceited when I say this, but I've had jobs where, I was clearly the the dumbest person in the room, and those are always my favorite. And I've had a couple of jobs where I felt like I was the smartest person in the room, and I really disliked those jobs. They just did not they weren't as fun. Right?

James Lewis:I liked being surrounded by people that every every time they talked, I learned something. Or I had to pretend like I was learning something because I I just couldn't understand what they were talking about.

Stephen Kraig:I guess, let's let's move on and talk about what our first jobs out of school was. Actually, Chris, would you mind starting us off with that?

Chris Gammell:Oh, really? Okay. I might be a little non standard. I I I thought that I was gonna be touring with my terrible terrible band at the end of college, and I did not. And, you know, no no offense to the old the old pals.

Chris Gammell:We're still very good friends, but we were not we were not good. And it would have gone very poorly. But one of them ended up getting into a doctoral program at John Hopkins. And so it was like, alright, you should probably go do that. Anyways, I was not paying attention that well.

Chris Gammell:And then I got a interview at Samsung. And Samsung was building a brand new chip fab in Austin, Texas. And they had seen on my resume that I worked on dry etch machines on the design of dry etch machines. And, then they're like, you could be a dry etch engineer. I'm like, okay.

Chris Gammell:And then they, you know, brought you down to Texas and showed you all around and took out all the fancy bars and restaurants, and that was in 06, and they've gotten a lot fancier. And yeah. So I started working at a chip fab without any knowledge. And, yeah, that was that was a a wild ride. You know?

Chris Gammell:Bunny bunny suits all day, all night. Oh, man.

James Lewis:That that that's interesting. I didn't realize that about you, Chris, because one of my one of the jobs I interviewed for out of school was at Austin semi Austin Samsung Semiconductor.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. Samsung Austin Semiconductor because what you just spelled would be ass. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Chris Gammell:But SAS is a very common yes. So Samsung Austin semi yes. Yeah. That's interesting. Yeah.

Chris Gammell:It you know, it's really so, like, silicon processing, super cool. Such a cool experience. I love my coworkers. I got to work with a bunch of people in Korea. I got to visit Korea for 7 months 7 weeks each other.

Chris Gammell:Super great experience. Terrible, terrible, terrible working conditions. Like on the Empire, we talked about, like, some of the stuff t m c TSMC is running into right now with moving to Arizona and, like, all the they're trying to open a new chip fab and just like the culture clash of, you know, Taiwan people that work, like, 996 and, like, Arizona engineers were, like, no. And and I felt that, like, in my bones. You know.

Chris Gammell:It's it's real. Cool experience. Do not do not recommend.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. My my oh,

Stephen Kraig:real quick. How long were you there for,

Chris Gammell:Chris? I was there about about 2 years, a little bit less than 2 years. And I was one of the ones that stayed the longest, except for the lifers. The lifers, I would say by of the starting class, probably 20% are lifers. And then probably, they had a pretty significant, like, probably 40% were gone within a year.

Chris Gammell:Rough.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I I I worked for an oil and gas company, a pipeline company in Oklahoma after college, because it was, like, basically, it was, like, the first people who would, like, respond to my resume. So and I was a instrumentation electronics technician out in the field up in, Elk City, Oklahoma, which is in, like, the middle of nowhere near, like, the Texas Panhandle. And and that was yeah. That was going out to the field stuff was actually not bad.

Parker Dillmann:I actually liked it a lot. It was having to deal with because I was like the only it was like it was like the company culture, I guess. I didn't really like it was if it was like, oh, if you put your your hard knocks in, we'll get you a desk job at the Tulsa building, and you can be a real engineer was, like, the term they used. And I was like, nah. And so I was there for 5 months, and then I moved back down to Houston.

Parker Dillmann:So, but I did learn a lot about just field work. I actually field work was, like, my favorite thing. But having to drive 6 hours to go to a compressor station just to flip a switch and then drive 6 hours back, that was a lot of fun that day.

Chris Gammell:Sun, you need IoT.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. No. That was the problem is the IoT part of it went down.

Chris Gammell:I know. I know. Yeah. You always need the backup finger that resets the original IoT. That's what you need.

Parker Dillmann:Exactly. Yeah. Yeah. So yeah. It was an interesting job.

Parker Dillmann:It was where you you were wearing bunny suits. I was wearing f r 2 fire resistance every day. So hard hats.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. Yeah. Mine was much more air conditioned, I think.

Parker Dillmann:No. It was hot, but it was it wasn't too bad.

Chris Gammell:Company vehicle. So so, James, you said you you interviewed at SAS. So where would you end up?

James Lewis:Yeah. So I I ended up as a application engineer for Agilent based in Austin, which the interesting thing was the year before, I was interning at Dell in the server group, and absolutely hated what I was doing. Yeah. Round Rock.

Parker Dillmann:Just Round Rock.

James Lewis:Like Fluker Rock. Yeah. And I really wasn't happy with what I was doing in terms of my team because everybody on my team had stock options that were all worth 6 or 7 digits. So they didn't really work very hard. Uh-huh.

James Lewis:So I started as I was talking to vendors in the lab, I was kinda, like, asking people what other kind of engineering jobs are there. And one of the people I was talking to was from, at the time, HP, and he was the application engineer for, their logic analyzers. And he told me all about his job and why it was cool and why I should think about something like that. And I was like, that's really cool. I I'd love to get a job like that.

James Lewis:Well, it turns out he had just gotten promoted and moved, away from Austin. So the following year, they hired me for his job. So I literally got the job. I said, I wish I could get a job like that.

Chris Gammell:Wow. And and everybody else, I'm sure, will have the exact same experience.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Precisely.

Chris Gammell:That is that is pretty awesome though.

James Lewis:Yeah. Yeah. The the one thing I wanted to say about that, though, is that was I feel like I got really lucky that I talked to somebody other than a we were talking about traditional engineers earlier. You know, I had no idea about something like application engineering or, in this case, a field application engineer doing either pre or post sales support of a of a product. Now, in the case of test equipment, I think it's pretty obvious the kinds of stuff you can do to to support equipment.

James Lewis:But then later on, I found you could be an application engineer for components or system level stuff for all kinds of things. And I think that sometimes gets overlooked as a engineering path simply because it's I think a lot of people think of it as just sales. And while there's definitely a sales component to it, you know, I I sort of, especially for the first part of my career, really stuck to the technical side of it. You know, for a long time, I I I couldn't even tell people what a total system would cost. I I had no idea.

James Lewis:I was not interested in any of that. But it was just interesting to me that my first job out of school was I thought I was going to sit behind a desk and play an Allegro or OrCAD all day, and instead, I drove around a car and talked to a different a different company almost every day. That's really cool.

Stephen Kraig:Right out of school, I it was 2,009. And at that point, I was just looking for anything I could get and hopped over to a company in in Houston that did oil and gas sensors, mainly vibration sensors for gas turbines and things of that sort. And I was originally hired on as a hardware design engineer, but, frankly, didn't end up doing a lot of hardware design there, not because they didn't trust me, but just because their design cycles were so long and they had tons of legacy equipment that they just didn't weren't really designing a whole lot of stuff. So I I really got a ton of time with manufacturing. I was I was very rarely at my desk.

Stephen Kraig:I was almost always on the floor doing something with, you know, fixing whatever manufacturing process was messed up or or in in improving the processes. And so it was it was really I feel like that was a really fantastic experience, because, first of all, I knew nothing about any of the electronics going into it. I knew nothing about what they were doing. I was just, like, great. These people wanna give me a job.

Stephen Kraig:And by the end of it, I had a ton of experience with we have a a thing in our mind, and we wanna actually get it built and we wanna make an assembly line and we wanna make a 100 of them a day. How do we actually do it? That was it was it was fantastic. But by the end of 4 years, I was kind of it just it just wasn't right for me. Ended up getting fairly sick of it, and I just decided to go off and do something else.

James Lewis:So so I was I was actually, I was going to ask you, what what did you not like about it? Or at the end of that 4 years, why did you why did you decide to to move on? Okay. So earlier when we

Stephen Kraig:were talking about why did you get into school, I I started doing audio electronics back in in high school, and that was really the whole reason why I even got into electronic or went to get my double e degree. And it was always my intent to make my way into that industry. And I was working in oil and gas, which was fine, but it was just generally boring. And getting into audio electronics is incredibly difficult because it's just super competitive and there's not a lot of opportunities out there. So I said, you know what?

Stephen Kraig:I I'll just do it. I'll just make it happen. So I left I left that company in the 1st place and started my own business doing audio electronics. Just I figured it was so hard to find a job doing it. I'll just just build a job doing it and ended up doing that for a handful of years, which was really a lot of fun.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. So we all had we're not doing our original jobs anymore.

Stephen Kraig:No. This is a good

Parker Dillmann:segue into changing jobs. A good good and bad reasons to change jobs. Like, for me, the I and E jobs, like, I wanted to do actual engineering work. I didn't wanna be a technician out in the field, and I wasn't gonna wait 2 years to do that. And I found I I found a job post for a funny effort, like, on the I wish that it still existed.

Parker Dillmann:Adafruit had a job board around, like, 2011, 2012 era. And, yeah, I used that and found a job. I was able to move back down to Houston. But that that was mostly I wasn't doing what I wanted to do. I went to school for embedded system design, and I was drawing wiring diagrams and pulling cables.

Chris Gammell:But think about how strong your forearms were getting. You know?

Stephen Kraig:But but but wait. You work on car wires wiring systems all the time, which is just drawing wires. I can't even see how it's coming.

Parker Dillmann:I can choose if I wanna do that or not and not have to worry about food.

James Lewis:So I think I think there is twice in my career that I I moved for at the time, a reason I thought made a lot of sense, but, in retrospect, I realized it was really silly and it was money. There were there were 2 jobs I took, 100% because I could get paid more money, and I overlooked so many red flags that I in one job, I I was even warned before I went in that I was told I was gonna look around and realize that the caliber of people I was surrounded by wasn't the same as I was used to, and I realized that, like, on day 2. And it was only within a few months I started looking for something else because I knew that I had made a mistake. And one of I what I found is, yes, there are certain times when changing jobs because of money makes sense, but if that is your only and primary motivator, I would really question if whatever you're about to take really makes sense. It can't be the only reason you change jobs.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. That's a that's a interesting point because I've certainly experienced this and I've been been told this for sure. But if you're looking to get a significant pay bump, most of the time, that changing jobs is a good way of doing that. But I I agree if that's your your primary motivator, you can very easily step in in something you don't want to.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. I wish you know, one of the things on on our list of things to talk about is things we wish we would have known, and I got completely lucky when I made my first job move. It was because I I had a bad working life balance and just everything was everything was rough about it. And I wasn't working on electronics. Right?

Chris Gammell:It was I was a chemical engineer, a process engineer, which is interesting, but not what I wanted to do. And and my buddy who worked at Keithley told me about an opening and helped helped me figure out what I should be studying in order to kinda get through get through the process and stuff like that which is really helpful. And I took it because it was just the only thing that was, like, grasping for like, literally oh, how about this? I am the only person who has ever moved from Austin, Texas back to Cleveland, Ohio in February. That is the only that is the only I'm the only person who's ever done that ever in history.

Chris Gammell:So that's how desperate I was. But the thing that was wonderful about it and the thing that I if I would've if I could point to one thing that made me successful because of it, it was because I was going to work with 30 20, 25 analog engineers, like, working on analog electronics. It was like, oh my god. If I could point to that if I could do that again, if I and every time I get give advice, it's just do that as much as possible at the beginning of your career. Right?

Chris Gammell:Just find as many smart people as you can to work around. And and if you do that, the money will come at some point. It might not be right at that point. But, man, if you could just load up on it was like it was going back to school. Basically, that was my graduate degree.

Chris Gammell:That's the closest I've ever come to a graduate degree is working at Keithley and, yeah. Working with those those those nice those nice midwestern smarty pants that I used to work with.

James Lewis:So I I wanna I wanna dovetail that because I know we're not quite to the point where we're talking about things I wish I would've known, but relate it to surround yourself by smart engineers, especially analog. I remember I was talking to not an official mentor of mine, but somebody I kinda, like, said, okay. I'm gonna use him as a mentor. I said, yo, so and so is a really brilliant engineer, but he is so impossible to talk to because he's just so rude and gruff and whatever. And my mentor, my my pseudo mentor told me, learn to look past that and just learn from him.

James Lewis:And, you know, I'm not saying put up with people that are terrible people. Just, I think one thing is to sometimes you have to look past a person's personality and listen to the things that you can actually learn from them. And that's that's something that I didn't do enough of, but I wish I had done more of throughout my career. Because I let too many times their personality would stop me from wanting to learn from them, and that that was very silly because there's lots of those people that you can learn good engineering stuff from. And in some ways, you can also learn people skills from them because you just sort of

Chris Gammell:not do whatever they do to. Yeah, exactly.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. You know what's funny about that? I actually turned down a job because of an individual like that. I I I once had an interview for a job that I thought was gonna be super cool. I I interviewed, I think, 3 times over the phone across a month and then they flew me out there and my my in person interview started at 9 in the morning and I didn't get back to my hotel until 9 at night.

Stephen Kraig:I interviewed with 10 different engineers. I interviewed with multiple different departments and the CEO of the company. And everything about that job sounded so cool, except there was one guy there that was just a complete ass. And and he was just he was just not great to interview with. And and, frankly, I just got a really bad feeling about the whole job because of that one individual, and I turned him down.

Stephen Kraig:I mean, I I took a flight back and and when I landed, they they called me and offered me the job. I'm, like, I'm I'm sorry. I can't do this. And, you know, you just gotta watch out for those kinds of things. And maybe that was a bad decision on on my behalf.

Stephen Kraig:I don't feel like it was, though.

James Lewis:Yeah. I think there's a real thin line there, you know. And I think I think in those situations, you really do have to listen to your gut. People can have kind of a gruff exterior, but they're still good people. They're just kind of, you know, maybe a little bit rough.

James Lewis:But when there's somebody that, especially during the interview process, that just just rubs you the wrong way, usually, it's probably better to to go with that because Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

James Lewis:There there's something there. And, you know, it's that's one of those things that, boy, if you get into a job and it's not put up with this person, it's, oh, I don't know that.

Parker Dillmann:Or that was or that was the one person that let the facade down.

James Lewis:That's another way to consider it too.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. This guy didn't tact wasn't in this guy's book. Let's just call it that way. I I remember the the the person I was interviewing with was in the room or who would have been my manager and and he would call in an engineer every 15, 20 minutes and I'd I'd interview with both of them all day long. And when this guy entered the room, he didn't come and shake my hand or whatever.

Stephen Kraig:He walks up to the whiteboard, grabs a marker, comes puts it in my hand and goes, draw the internals of an op amp. And and so, like, he just wanted to see it. And what was funny was, like, I was it's it's maybe it was serendipitous, but I I studied that actually before going for for this. So I was able to answer all these guys' questions, but it's just, man, didn't really like the way you handled that. Why don't

Chris Gammell:we Our name and shame. Let's hear these people's names. Let's call them out right now.

Stephen Kraig:I actually don't even know what to do.

Chris Gammell:This is why we started doing media stuff, so we can get back at people. You know what I mean? Get back to Exactly. 15 years later, you're gonna hear from me on a podcast you never listen to. You know what's funny?

Chris Gammell:Friends do either.

Parker Dillmann:It's really funny about this this this that a particular individual like that. At my first job at the oil and gas company, when I put in my 2 weeks, they haven't they asked me if my supervisor was the reason why. Because he was that person that had the that edge to him, I guess. And I actually I didn't have that any problem with this person at all, and I learned a lot from him. And I was like, no.

Parker Dillmann:This don't know why. I haven't heard this in the interview process. You'll be working for this person who's kind of a, you know, an ass. And I'm like, he's an Austin Samsung semiconductor company. And I I didn't get that at all.

Parker Dillmann:Sure. Yeah. He was a little rough on around the edges, but, you know, got along with him just fine, and that was the reason why I switched.

Stephen Kraig:I actually just had a conversation with my boss the other day about this exact same topic. And I was mentioning to him, I was like, you know what? This this team is really cool. We don't have anyone who's really rubs anyone the wrong way or has just a sandpaper attitude about things. And and he and my boss just turns to me and goes, yeah.

Stephen Kraig:I don't hire assholes. So why don't we get to the question of things I wish I knew back then? What are things you wish

Parker Dillmann:you knew back in your first job? I wish I knew what y'all knew, which was go learn with or go go get hired by a place that has 20 engineers you can learn from. Because that's actually never been an experience I've been able to have. Like, the oil and gas place, I was always I was the only

Chris Gammell:Don't you work at a monster electronics company now in Parker?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. But I'm, like, the lead electrical engineer. I never I never worked under someone.

Chris Gammell:Beginner's mind, man. Beginner's mind.

Parker Dillmann:I never actually, I I do. When we when we started actually building the engineering team here, it was really weird because I was, like, the lead, but I was the one who was, like, hiring experienced testing engineers.

Chris Gammell:Parker in interviews is, alright. What are you gonna teach me?

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. What yeah. Interview me.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. Exactly. No. Don't interview me. Just tell pour your knowledge into my brain, please.

Chris Gammell:That is

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I like, when we I had built a test engineering team. I'm like, I have no like, I know some stuff about test engineering, but not, you know, 10 years of test engineering. So having to figure out what makes a good test engineer, what makes good processes for all that, like, I had to go learn that from people that have been doing it, and I had to hire them. So that was really weird.

Parker Dillmann:So I wish I wish I had that experience of actually working with senior engineers that I was under. That might contribute a lot to that FOMO and and Would

Chris Gammell:you like to hire one of us as the senior senior lead engineer at MacroFab, and then we could tell you what to do, Parker?

Parker Dillmann:There we go. I need people to tell

James Lewis:me what to do. Maybe we could be co lead engineers.

Parker Dillmann:Co leads. Yeah. No, I I could I switch to marketing recently and I'm like, Guys, you need to tell me what to do. Like, I'm fish out of water in the marketing department. Tell me what to do.

Chris Gammell:Something something analytics. Yeah. I yeah. I I don't know. I wish I would have I think I wish I would have gotten started coding

Parker Dillmann:sooner?

Chris Gammell:I I I think this is something that they even my coworkers wouldn't have told me. It's just like being more kind of one of the downsides, maybe this is a good, counterpoint to this is so I went to a place with tons of really in like super deep technical knowledge people. They were clueless though about they, you know, I I I love I love them. They're many of them are still there and they're they're designing great products. But there are no other places.

Chris Gammell:Like when you look at what other so this is one thing that scared me away from Samsung as well. Is I was looking around and there were people that were there 15 years senior to me. You know, who were, you know, senior title whatever. But they were doing the same thing I was. Just at and then they were telling me what to do.

Chris Gammell:And and I was like, I don't want that. I don't like that that kind of thing. And and so then looking at the same thing at a Keithley, where do you go from here? There is no up. You know, like, there is no there is no side.

Chris Gammell:You couldn't even you you weren't even you know, so you're an analog engineer. You're working on this super high end 8 8 and a half digit DMM, super cool stuff. But, like, the next thing is to design another one of those. You know, it's not go learn FPGAs because there's no money to go and do that sort of thing. So for me, the thing that I wish I would have known sooner was just like get as much knowledge as you can, learn as much in this deep area and then hop.

Chris Gammell:Hop to the next the next hold rabbit hole to dive down. And that's something that, like, even now I struggle with it. Right? I because I think the real hard thing is that you're putting yourself in a position where, you know, as we get as I get older and I get grumpier and I I don't know a lot of things, I'm just, like, frustrated, like, all the time. And I'm trying to reintroduce that to my life a lot.

Chris Gammell:But it's tough. It's tough to do that. So but pushing myself to do that more, I wish I would have known that sooner. You know? Because you you expand and you can do cooler things.

James Lewis:Yeah. I think related to that, I was going to say, I wish I had known to have a plan, but it's okay to change your plan. Right? And so when I first started, I thought I wanted to know everything about designing wide bandwidth RF amplifiers, and very quickly, I didn't like that at all. Right?

James Lewis:And but I was really afraid to ever talk about that because I thought, oh, then people are gonna think I'm flighty. But, I think it's important it's important to know to have a plan and that that plan can change. You know, I think I think there's some people that are like you, Chris, that, you know, you wanna learn everything about everything, and then there are some people that just wanna learn a lot about in one topic. Right? I think I'll bet there are some people who heard you say you could only move in you couldn't really move upward or was, laterally or horizontally, or is that the same thing, within a company, but there's, I think, some engineers that want that.

James Lewis:They wanna keep doing the same kind of thing

Chris Gammell:for Yeah.

James Lewis:Yeah. 20 or 30 years. And that's okay, and I think the important thing is that's okay, and if that's your plan, then fine. Make that your plan. If you want to be able to move around, then yeah, you need to really think about how you're going to change do that.

Chris Gammell:Know thyself, you're saying. Yeah?

James Lewis:Oh, I like that. Yeah. Yeah. The the less serious thing I was gonna say is I wish I had learned how to use Git or any kind of version control at some point in my life before the last, like, I I would only say in the last 5 years have I actually finally understood how to do something other than git clone?

Parker Dillmann:Git command line still scares me.

Chris Gammell:Oh, yeah. I mean, the water's fine.

James Lewis:I I use I I use a GUI all the time.

Stephen Kraig:I use a GUI

Parker Dillmann:all the time too.

James Lewis:Yeah. Unless I find something that says you have to put this magic command in because as much as I love using command line interfaces, get command line also scares me.

Chris Gammell:There you go. Make yourself uncomfortable. You'll get there. You know, the other thing I was thinking about, career wise is I wish I would have bought Bitcoin and Apple at the bottom. It's just

Parker Dillmann:Now you're just coming up with

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Now you're just coming up with regrets. I mean,

Chris Gammell:come on. Why not, guys?

Stephen Kraig:I think one of the things that I wish I would've known back at the beginning was how to say no. I I said yes to absolutely everything. And I said that because I really wanted to learn everything and just get involved and be useful at everything. And in a lot of ways, that made me not useful at a lot of things. It could just just I said yes to way more than I could handle, and everyone was willing to give me what I said yes to.

Stephen Kraig:And I ended up failing at a a decent amount of things just because I couldn't handle it. And and and I I really wish I learned that quicker to just be like, no. I can't handle this. This is my workload. This is my knowledge base.

Stephen Kraig:This is where I'm at right now. So

James Lewis:I I wish I could still learn how to do that.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah.

Stephen Kraig:Prioritization doesn't matter if you if your list is so long that prioritization doesn't even fix it. Right? At at some point, you're just you're just always working on the thing on the top of the heap, but the heap never changes.

Parker Dillmann:You're attacking every single person that listens and is in this podcast right now. Yeah. Because that was that was one thing is, like, having to pit the pivot on that one. I wish I learned that just buying the parts isn't the biggest problem with the project.

Stephen Kraig:That's a good point. I'm gonna

Parker Dillmann:shove all these parts further underneath my my bench here.

Stephen Kraig:In the opposite way too. You can't be afraid to say no but you also need to be able to use that appropriately. I I mean, there's there's no words of wisdom here. Just just learn. That's all I can say.

James Lewis:I think I think I I might be able to rephrase what you're putting together is, you know, you need to learn when to say no Yeah. And it's probably more often than you realize. I I and I think that's one of those things that I wish I I had gotten better at that early in my career, but that's definitely one that if I look at all the things I could work on at any point moving forward, learning to prioritize and say no is probably always going to be on the list. Or at least I hope it is, because it means I wanna try to learn how to do everything.

Parker Dillmann:Prioritize to learn to prioritize.

James Lewis:This reminds me of something somebody said to me when I was this was my 1st or second, year out of school, and I'll never forget how weird this sounded. So, he called me, this co worker called me up and said,

Chris Gammell:I'm so sorry it's taking me so

James Lewis:long to call you. I am planning to become more proactive in the future.

Stephen Kraig:I like that.

James Lewis:I just thought, why don't you just do it now? How do you plan to become proactive? That that's like the opposite.

Stephen Kraig:It's like there's this date where they're like, I am proactive now.

Parker Dillmann:Maybe they have a KPI where they can measure their proactiveness.

James Lewis:Proact man, that would actually be how would you measure that? Would would it be like getting things done without putting them up, putting them on your to do list?

Parker Dillmann:No. You put them on your to do this and then immediately cross it out because you've already done it. See, I started doing that on the weekends and that made my life so much better.

James Lewis:You have a lot less to do now.

Parker Dillmann:It makes your list look more impressive. This is, like, one of those interview questions. Right? Which is so so we talked about our our careers in the past and stuff like that and present. So where do we see yourselves in the next 5 years?

Parker Dillmann:And then on on the flip side of that is, what was the answer to that question 5 years ago?

Chris Gammell:5 years. I would say as for me, I'll repeat what I I've told my boss when we he's brought up career before. He's, you know, like, where do you where do you see your career going and and whatever. And I've I've said, you know, no matter no matter what, if if things go really poorly or things go really well with the startup I work at, and I I I think it's gonna be the latter, then I'm probably gonna be a hardware consultant again, you know. So I think probably designing electronics for people for money.

Chris Gammell:It's probably it's kind of my goal and talking about electronics with fellow nerds.

Stephen Kraig:Well

James Lewis:Yeah. I think

Parker Dillmann:Go ahead.

James Lewis:Go ahead, Parker.

Parker Dillmann:No. No. No.

Chris Gammell:No. Go ahead.

Stephen Kraig:Oh,

Parker Dillmann:yeah. That's kind of where I'm at, I guess. It kind of threw a little curveball when I had to move over to marketing to help out the marketing team here at Macrofab because I was doing that. I guess I I had finally gotten into a position where I was like, okay. We got the engineering team all dialed in.

Parker Dillmann:We have a test engineering team, we have quality, etcetera etcetera. And I'm like, cool. Now I can get back to like building stuff that's helping like us build other things. And then I was starting to drum that up and they're like, hey, Parker. You know what?

Parker Dillmann:You should move over back over to marketing again because I was like when Steven was at at MacroFab, I was in marketing, and I was also, like, product product and stuff. Anyways, they I so so I went back into marketing. So that was kinda like something I did not foresee see happening again. Was moving back to marketing full time. They start doing some projects in marketing that allows me to design stuff.

Parker Dillmann:We'll see though. It's always the wish.

James Lewis:You can always make demo boards.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. I found is it's it's really hard to get customers to allow you to take photos of their stuff. Designing stuff that I I own is easy to take photos of doing that. Make our own content easier.

James Lewis:Yeah. So when I when I when I use this 5 year sliding window, like, I didn't think about the 5 years ago and then 5 years from now, you know, the one content, and every time this question has ever been posed to me, I, you know, I always struggle with, I I I can't tell you where I'm going to be in 5 years. I can tell you where I think I'm going, and, you know, to me, what's what's continuing to be interesting about my my path forward is it's

Chris Gammell:it's always going to be electronics related, or at least today, when

James Lewis:I look forward, something I'm going to be doing is going to be electronics related. Maybe I won't be a content creator in 5 years, but I'll I'll be doing something electronically related. In terms of career and making money, there's not a lot of other things that really interest me. Now, I've got plenty of other hobbies that I'm interested in, but I don't wanna make those a job or a career. I think that's at least the one con content, not content, one constant that I can see in that sliding window.

Stephen Kraig:You know, I I think if you had asked me this exact same question a handful of years ago, I would have probably a lot more specific of an answer saying, oh, in 5 years, I want to be x y z engineer doing this particular type of work. And and as I've gotten a little bit older and throughout, a handful of job changes, I'm not really that, unfamiliar or scared of making drastic changes to what I do for a paycheck. And so, I think in 5 years, basically, all I can say is regardless of what I I do, I just want to be a trusted resource and a capable engineer at whatever that is. So people can rely on me to execute on what I need to do regardless of it.

James Lewis:You know, you said something, Steven, right at the start there. If you asked me when I was a year or 2 out of school, what do I what do I think I'm gonna where where do I think I'm gonna be in 5 years? I had a, I wanna be this title doing this job in 5 years. And it was probably after about 10 years that I stopped having that as my my my end point or my plan. It was I wanted to kinda my pan my plan became much more broader than this specific position, which is, like, why I I think, like, today, I would have a hard time saying this is the job title I want 5 years from now.

James Lewis:I just don't see how I could could pick that.

Stephen Kraig:I I think, honestly, for me, a good day of work is I go in, I I I see the challenge that's ahead of me for that day or whatever is required of me and I execute faithfully, and I feel confident of the work that I did and I leave. That's like a just a a definition of a good day for me. If if I can be in a position in 5 years, I mean, it's not that I'm not doing that right now. It's just I would like to also be doing that in 5 years.

James Lewis:So I think the answer to all of all of us is 5 years from now, we would still like to be making money doing a job.

Stephen Kraig:I like that. Yeah. That's a good one. More

Parker Dillmann:related to electronics.

James Lewis:Which may or may not be related to electronics.

Stephen Kraig:I think it'll probably

James Lewis:That's a good career advice. Is

Chris Gammell:the definition of electronics is probably gonna

Stephen Kraig:change for me.

Chris Gammell:I think, you know, you know, I

Stephen Kraig:think about what's how

Chris Gammell:things are different now than when I started, whatever. But, yeah, there be electricity involved, right?

James Lewis:Yeah. I guess I guess it'd be maybe it's more accurate to say engineering instead of electronics.

Stephen Kraig:Mhmm.

James Lewis:I don't know. At least for me,

Chris Gammell:I could

James Lewis:see Yeah. Problem solving. Yeah. Yeah. What

Chris Gammell:I hear James saying is that Chat GPT is coming for all our jobs. That's why I hear the fear in his voice.

James Lewis:I'm not worried about I'm not actually worried about Chat GPT taking my job. I'm worried about people thinking they can replace me with Chat GPT.

Chris Gammell:And then you have to fix all their crap. Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:That's gonna be that's gonna

Chris Gammell:be a good

Parker Dillmann:AI. AI fixers.

Chris Gammell:That's gonna be the job for many years. Yeah. Yep.

Parker Dillmann:Alright. I have some random other questions here I wrote down right before the start. So what is the most non engineering job you ever had? And did that influence your decision to go into engineering or taking another job?

James Lewis:I wanna go first.

Parker Dillmann:You go for it.

Stephen Kraig:When I

James Lewis:was in high school, I worked at a

Chris Gammell:pizza place. The positive to that is we did everything by hand and from scratch, and it was awesome, which is something I still try to do as

James Lewis:a hobby today. But I'll never forget one of the guys that had been he was a driver. He wasn't even working in the kitchen. He'd been working there for, I don't know, almost 10 years, and he came up to me and he said, hey, James. I heard you're going to go to college instead of stay home and and and, you know, just get a job here.

James Lewis:I want you to rethink that because they're talking about making you the assistant manager, and you could be making

Chris Gammell:Assistant to the regional manager.

James Lewis:Actually, it would have been because at the time, I I would I was only 16 or 17, so I wasn't even 18 yet. So it would be a year before I could become the actual man be be a manager. But he he finished the line with, so they're thinking about making you the assistant manager. You could make 6 or even $7 an hour if you stay. Nice.

James Lewis:And I made sure after that, I never had a job where I had to consider that as an option.

Parker Dillmann:I had in college, I worked for any of furthest away from engineering by work for the engineering departments, but I was sorting mail, making sure the printers had toner. And then so, you know, we're, like, at the end of the year, you always do. There's, like, a survey. You do if, like, how much you hated your professor. So I had to go and collect all those and then push them all to, like, the one building on campus that would do all the sorting for that.

Parker Dillmann:And what was interesting about that was I got really good at just talking the shop with other people around the campus because the other people had access to the lifts in all the other buildings because the campus I was on was really hilly and so you got I got to the point where I never had to actually push the cart up a hill. I knew where to maneuver it to what building I can get to what level to, like, just go straight out, around.

James Lewis:So you you optimize your path?

Parker Dillmann:It was long it was it took longer to push it, but at least I didn't have to push it uphill in a 110 degree weather or in snow. I didn't have to push it uphill in snow either. But that was the funny that I worked for the engineering department was the farthest away from engineering you could possibly be.

Stephen Kraig:One summer, I worked at Walmart in the in the garden department and this was a summer in Houston, Texas. And I was the guy that lawn crews would come up and they would order a 100 bags of mulch or pallets of bricks and the entire crew would get out of the car and just sit there with their arms folded and watch me stack bricks in the back of their truck or throw bags of mulch in a 100 110 degree weather. And, you know, I was really skinny then. It was that was that was nice, but I couldn't I couldn't wait to get back to college after doing

Chris Gammell:that. Well, I had very similar, you know, similar kind of experience. So I'll talk about a little bit different one where I I I exited engineering for a while, where I went to go work for supply frame and I was doing management, whatever. You know, I looked I love supply frame. I love the hackaday folks, stuff like that.

Chris Gammell:But I was basically, like, learning how to do product management for websites. Right? So it was like a it was right turn for me. And I, you know, I I knew marketing sort of the amp hour and past stuff and blogs and whatever. But, yeah, that's not for me.

Chris Gammell:And so I couldn't, you know, I like I said, I love working there. I love, you know, the variety of things, but that was very non engine even though it was the engineering adjacent, it was like, I was not not hands on. I was very grumpy a lot of the times. Yeah. Wasn't doing electronics in my spare time because I was so exhausted from the the things.

Chris Gammell:I was working remote. Learned a lot of things there but learned that I really liked designing stuff and got my jollies from, building stuff.

Parker Dillmann:You know, it's interesting you saw that you said that you stopped doing electronics for fun as a hobby. When I switched over to marketing, that actually kinda, like, reinvigorated my hobby for electronics because I was doing that kind of stuff at work, and I was just, like, kinda exhausted of doing that at home. And then Yeah.

Chris Gammell:That's a good point. Yeah. I guess I did do I did contextual electronics around then, though. So there was that. Yeah.

Chris Gammell:I was already doing contextual electronics as like the the other thing. But then that tailed off too because of just other things, you know. So Yeah. Alright. There's only so many hours in the day and how much, like, brain space you can put towards things.

Chris Gammell:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Exactly. So I don't have an answer for this question. But if you could have dinner with any famous engineer, dead or alive, I didn't know there was famous engineers, but maybe we can make famous engineers. Who would it be and what question would you ask them?

Parker Dillmann:And then also, what are you eating?

Chris Gammell:Parker, who wrote that question? Was that chat GPTU or is that you?

Parker Dillmann:That's totally chat GPTU. That's not

Chris Gammell:me. I knew it.

Stephen Kraig:I like this question a lot. I've got a quick answer to that.

Chris Gammell:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:Okay. You don't like this

Chris Gammell:one, Chris? I don't like this one. I mean, it's it's alright. I'll answer it. I'm here, you know, I'm here to play, guys.

Chris Gammell:I'll answer it, but you go ahead, Steven.

Stephen Kraig:Okay. Yeah. I I I got a quick one. One thing that's fascinated me, I don't know if you guys have ever researched this, but back in World War 2, the US was cranking out B 17 bombers. A new bomber every 45 minutes or something like that.

Stephen Kraig:I would love to meet the engineer who planned the entire manufacturing facility of Boeing to be able to do that without computers whatsoever and be able to manage supply frame or supply frame supply chain and all of the processes to get that just right? Holy yeah. That that guy should be a famous engineer. What are you eating? Jalapeno jalapeno lime pistachios.

Chris Gammell:Did they have that in the forties?

Stephen Kraig:No no other famous engineers?

Chris Gammell:James James has got one. He's got one, Bruno. I could see. Yeah. I could see.

James Lewis:Yeah. I've got it. I've got one, but it's it's somewhat timely. It it it'd have to be Steve Wozniak. There's a whole bunch of applications I really wanna ask him.

James Lewis:And in terms of dinner, we'd have to go someplace to serve steak because I wanna find out if he actually does use his metal business card to cut speak with it.

Chris Gammell:Go ahead, Parker. I'll go last because I I'm still I'm still

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. That's the thing is I saw that I Chatchip PD splat out this question. I'm like, I like it, but I don't have an answer for it. Mhmm. You know, because I do a lot of car stuff.

Parker Dillmann:The engineers that were behind the kinda like how the model the model a was, like, the first real ish assembly line for automotive. What that was like trying to set that up? I don't know if Ford is actually behind that or not. I think he's credited towards that, but it could've just been his idea and not he didn't implement it. I don't know.

Parker Dillmann:But that that's what I would like to to talk to is, like, how was or I would like to have on the podcast is that person that implemented that's that going from hand fitting everything and having the hand make everything and one off batches to now we are going to try to build an assembly line to just build something that's interchangeable parts. I think that whole interchangeable part thing was something that, like, fascinated me when I was a kid. And we use in electronics, everything is an interchangeable part.

James Lewis:That also fascinated me as a kid because I couldn't see any other

Chris Gammell:way to do it. It just

James Lewis:seemed so obvious to me that why wouldn't everything be built that way, so the school learned that we used to build everything by hand or, you know, one off was it just didn't it just just didn't resonate with me.

Parker Dillmann:And I would be eating probably a burger. Burger and fries. Steak fries, though.

James Lewis:Not a burger place that does it on an assembly line?

Stephen Kraig:No. By hand. No handmade burgers.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Each each French fry has to would come back together into the perfect potato it came from. You know what's interesting is is we'll see what Chris says, but James is the only person who's actually put a name to who they'd be eating dinner with.

James Lewis:I I do I do if if maybe if you use the question in the future, if you change it to group of engineers, maybe that makes it a little less intimidating because I like both of your answers so far. But Chris is going to have the best answer.

Chris Gammell:We we I'm really not. I don't know. I yeah. I've been thinking through, you know, ones that I've, yeah, quasi idolized, but they're also idiosyncratic too, you know, like Bob Peace and Jim Williams and all them. I don't I don't think I wanna hang out with these guys, you know.

Chris Gammell:I I think, like, like, they were experts. I would have loved to learn from them, have a meal with them, maybe, you know, I think What

James Lewis:about lunch? What what if you could have lunch with one of them? Would that make it different?

Chris Gammell:Yeah. If I could have lunch with a group for like a couple months, that'd be cool. That's asking a lot, I suppose. Guess I'd be working can I go right there? You know?

Chris Gammell:I don't know.

Parker Dillmann:You know, that's actually, you know, rephrasing to be what engineer you would like to work with in history Yeah. Would be better,

Stephen Kraig:I think. Yeah.

Chris Gammell:We

Parker Dillmann:can change the question just for you, Chris.

Chris Gammell:No. It's okay. I don't I don't really have a good, you know. And then there's all the Bell Labs folks too. You know, like, if you read, like, the idea factory

Stephen Kraig:Mhmm.

Chris Gammell:That's a great book. Excuse me. Yeah. I think, you know, people in that, Claude Shannon, sure. Let's go with him.

Chris Gammell:And I'd be eating whatever's I probably wouldn't be eating whatever's on the menu at the Bell Labs cafeteria because it's probably boiled. You know, cuisine back then was pretty bad. Salad. Jell O. I've been eating a lot of pudding lately actually.

Chris Gammell:I've been rediscovering Jell O pudding. I this is here's a fact you guys didn't need to know about me. I have kids, so I've been eating jello pudding, and it's joyful. I do recommend picking some up.

Stephen Kraig:Does it bring back good memories?

Chris Gammell:Brings back immediate memories. I mean, I'm I'm having the time of my life right now, guys. Pudding. I got some pistachio pudding downstairs.

Stephen Kraig:Nice.

Chris Gammell:Ways to sound old. 101. Looking forward to one of those cup of soup. Some pistachio pudding.

Parker Dillmann:That's the most bizarre request you've ever had to handle and how did you make it work? That one I did right, Chris.

James Lewis:Champ. Champ.

Stephen Kraig:Be quick on this one. I got I once got asked to to to to design the distribution station for a very large weed growing plant, and this was not in Colorado. And I very quickly was like, nah. I don't wanna be a part of this. This does not sound like fun.

Chris Gammell:Would've gotten paid in cash probably.

Stephen Kraig:Probably. Under under the table.

James Lewis:This isn't super bizarre, but I felt it was awkward. I was asked to hand deliver a basically a probe. It was like a $30,000 probe to a customer. So I was living in Austin. I had to drive it to Houston, drop it off at their front desk, and then drive it back home.

James Lewis:For reasons, they did not want us to send it by courier. It had to be an employee, so I was asked to make the 4 and a half hour drive to literally drop off a box.

Stephen Kraig:White glove service. Okay.

Parker Dillmann:I've done that before, though, but with customer products here in Houston, I I never had to drive to Austin to do that that drive yet.

Stephen Kraig:I I carried a box the other day through our office that had many 100 of 1,000 of dollars worth of parts in it, and it was not a courier. It was just like UPS that just dropped it off.

Parker Dillmann:It's insured just the basic $100 amount.

Stephen Kraig:With a lock? No. It was just a cardboard box.

Parker Dillmann:It's like, cool. I guess. I'll I'll actually gonna make it, like, awkward things is when people ask me to work on their projects, and it's not that interesting to me. That might be like everyone here, though.

James Lewis:Yeah, that that's a really good time to learn how to say no.

Stephen Kraig:Yeah. Because I I

Parker Dillmann:have said yes to a lot of those and end up, like, hating myself down the road.

Stephen Kraig:You know, that that's a good way to learn because it's not that hard to say no.

Parker Dillmann:Right? Mhmm.

Chris Gammell:And I

Parker Dillmann:always feel like I'm letting that person down or and I I what I've learned is I try to pivot to be like because clearly they're asking you for a reason, and it's because they might think you are better at doing it or you have information. And so I try to pivot to be more like a consultant for that project other than just saying flat out no. That way I don't do the real work. I get to do the fun work of drinking a beer and talking to them about it.

Chris Gammell:For me, I I had a internship or coop, really, when I was, like, my first my first job in I still in college. And I don't remember how it got out, but one of the product managers, she was very boisterous and she learned that I had I was, like, taking Japanese classes. And she's and so one day, she's, hey, Chris. Come over here. I'm like, okay.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. What's up? I don't remember her name at this point. Peggy, maybe. I don't remember.

Chris Gammell:She said, hey. Come in here. She pushes me into a room and she says, these men are from Kawasaki. Speak some Japanese to them. And I'm like, oh my gosh.

Chris Gammell:I did not do well, guys. I did not do well.

Parker Dillmann:Did did they land the deal though?

Chris Gammell:They did. They did.

Parker Dillmann:Then you you successfully completed the task.

Chris Gammell:And they were probably entertaining. Of me. They yeah. Yeah. I'm I'm sure they I'm sure they were giggling much later about the the poor college kid from Ohio.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. Turns out when you bring Japanese businessmen to Cleveland, Ohio, not a lot of things going on there for Japanese language.

James Lewis:Go figure. That's so weird. I would have thought that'd be, like, a epicenter.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. Right. Right. Actually, Columbus is, though. 2 hours off.

Parker Dillmann:We wanna wrap up the podcast, I guess?

Stephen Kraig:Yeah.

Parker Dillmann:They won't have anything else to add about their careers or anything?

Chris Gammell:The best days are ahead of us, boys. You know, we didn't talk about content generation at all. I thought that would have been part of it. I guess I didn't should have added that to the list. But we all kind of pivoted to being on screens, talking to other people.

Chris Gammell:Yeah. I guess the question would be, you know, would you recommend this kind of stuff in addition to you know, we're all still hardware, hardware adjacent, interested in hardware, whatever. But is it worthwhile? Should people be considering it as part of their cornucopia of skills that they bring on? I'm going to just straight up say yes.

Chris Gammell:I think social media is something that's here to stay. It's not new anymore. It's ingrained in, I think, a lot of people that might be graduating from college right now. They grew up with it, and I

James Lewis:think you need to learn how to present the work that you do. Even if you don't participate in social media, there's, like, a cultural expectation in the way that you present the information you share with others. Even in, I think within an engineering group, I think being able to create to have an idea about how content gets created and is is consumable by people is going to continue to be important.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Even slideshows is content creation. It might not be a 100% public, but it is to your peers. I I never thought I'd still be doing the podcast after 435 episodes, but here we are and I enjoy it. This is probably my favorite thing at macro fad to do so hopefully it keeps going.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Chris has 660 I thought it was 666 a couple of weeks ago.

Chris Gammell:671 this will be. Okay. Yep. Yeah. Yeah.

Chris Gammell:I think I think look at what people are doing now and assume that, you know, the the 4 of us are talking over audio, and it's probably not the medium that's gonna be, you know, like, it's been going a long time, but it's probably not just this and it's probably not the highest growth rate sort of thing. So I think, yeah, kinda like what James said, be able to talk about your own work, be able to, you know, get yourself out there. Put yourself in Hacker News. Find like minded people. I think finding community is probably the most important thing there even if it's not.

Chris Gammell:You don't have to be a content creator in the the TikTok sense of the word or even the podcast sense of the word. But I think finding people to get excited about a topic with and it doesn't have to just be electronics either. It could be it could be a super niche area. It could be kind of higher level. It could be, you know, generative circuit board design or something like it.

Chris Gammell:Right? But just find your find your crowd and then geek out, you know.

Parker Dillmann:Find find that form. I still have

Chris Gammell:some some people, yo.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. Find that form that's got that niche. Yeah. Yeah. That was the MacroFab Engineering podcast.

Parker Dillmann:No. It's I've done that how many times now, Steven?

Stephen Kraig:It's it's still ingrained.

Parker Dillmann:Yeah. It's burrowed into my brain. Thank you for listening.

Chris Gammell:Zap, zap, zap, zap, zap. This is circuit break. Zap, zap, zap, zap, zap, zap, zap, zap, zap, zap. Yo. Editor, keep that in.