Creators and Guests

What is Me, Myself & TBI: Facing Traumatic Brain Injury Head On ?

Me, Myself & TBI: Facing Traumatic Brain Injury Head On provides information and inspiration for people affected by brain injury. Each episode, journalist and TBI survivor Christina Brown Fisher speaks with people affected by brain injury. Listen to dive deep into their stories and lessons learned.

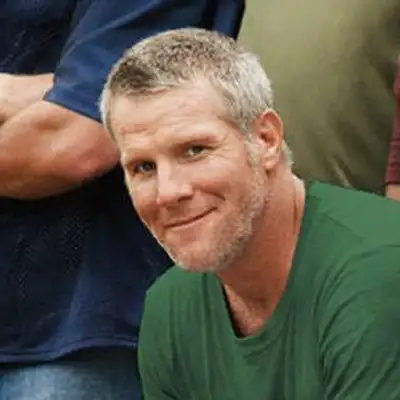

Christina Brown Fisher:

You know, I feel like you don't a need introduction. You're a walking legend. But, you know, for some people, who don't know, I am talking to Brett Farve, who was a backup punter and became an NFL legend. 20 years in the NFL, 16 with the green Bay Packers, where, led the team to your Super Bowl championship. But it came at a pretty hefty cost. Brett, you have talked about the fact that you suspect that over the years you likely suffered thousands of, or at least a thousand concussions. One let me just start with, how are you feeling today?

Brett Favre:

All things considered, pretty good. I'm 54. I've had, I would say, a rough year and a half.

Christina Brown Fisher:

How so?

Brett Favre:

Not so much from a mental perspective, but I had my right hip replaced, which is not these days is not uncommon, and that went well, and then I had back surgery, so it's been roughly almost a year when I had back surgery. And, you know, what's interesting is, throughout my 20-year career in the National Football League, my right hip, which is what I got replaced, I had problems with it throughout my career, on and off, and I was able to play through it. But it finally caught up with me, so I had it replaced. But, but I never had back issues. Which is you would think playing 20 years in the National Football League and 19 of those years, never missing a game that you'd have had some back issues. You would have thought that, you would have thought that I would have had, many issues. Not just back, not just hip. And, yes, I did have injuries, they were injuries that almost kept me out of the game, but, but all in all, you know, I was able to play. But at 52, which was two years ago, I started having some back issues. And, from there it just got worse. So here we are a year later and we're sort of contemplating surgery again, and we're, I'm doing one, one more procedure. It's kind of a, you know, the, the last guy in the bullpen, if you will, and it's a it's a spinal cord stimulator. And they connect, this, looks like a little paddle with two, two wires to it, to the spinal cord above the pain area, and you, it's sort like a pacemaker, you know a little module that, the first 5 to 7 days, it's a, it's a trial. So, if it works this module you'll have outside of the skin. If it works, they will implant it under the skin it disrupts the pain waves that go up to the brain and sort of tricks it, that it's not as painful…

Christina Brown Fisher:

Given all that your body has endured, because of your career in the NFL. What kind of regrets, if any, do you have given how much you've suffered physically?

Brett Favre:

That’s a great question, there’s not a day goes by, or anything that I do, I’m constantly reminded that if I went back knowing what I know now, what would I have done different? And, you know, I thought about that question, really, in depth, and you know what what's weird is, I don't know if I would have done anything different. Just based on my personality, especially, you know, if we think.

Christina Brown Fisher:

You don't think you would have played different? You don't think there would have been a different style of play?

Brett Favre:

I think if anything, I would have been a little less, reckless.

Christina Brown Fisher:

What do you mean by reckless? What in your career to you, do you define as reckless?

Brett Favre:

Yeah, I think I look at my my 20 years and and it's, you know, I look at it as in phases and and what I mean by that, if you think back to when you were in grade school. So, your first grade, second grade, and third grade years versus year ten and 11 and 12 year, years. You know, roughly graduate high school at 18. You start first grade at seven or eight. There is a dramatic difference, in a seven and eight years old versus 17 and 18 years old. There's a transformation from first grade to twelth grade. That is that is, you know, a huge difference. And then pro football for me, I kinda compare that, you know, early years to. You know, my rookie year I thought I was ten feet tall and bulletproof. And, and in some respects, I was and we all are at 21, 22, but 39 and 40 I remember, how difficult it was to just get up and go to practice and do the things I needed to do and be the player I needed to be because everything hurt. My joints, my ankles, my hips, back, didn't give me hope, be it, it would be stiff, and it was just hard to get yourself going at 21, 22, quite frankly, 27, 28 you know, really my twenties was like play a game Sunday. You know, most fortunately, we won most of those games, but, but I would get beat up, but by, and that would be, you know, Sunday. By Wednesday I was good to go. I mean, I had recovered and had forgotten about the you know, the, the hits and the aches and pains, by you know, in three days. Where the latter part of my career, come the next game. I was still feeling the previous game.

Christina Brown Fisher:

And when you say that, you are still feeling the hits, are you talking about the physical? Or are you talking about the cognitive impact of hits to the head as well?

Brett Favre:

More, more, you know, more of the physical.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay.

Brett Favre:

You know, the thing about the mental part of it, um, and I'm sure you're well aware, this is a lot of times you don't feel anything. You may, you may have had a concussion, whether you knew it or not. You know, and we have to go back, you know, to to my career and how concussion. Even though it was not that long ago I retired, I think in like '11 or '10. You know, that's not that long ago. But in in the, in the concussion world, it is a long time ago because in year ten for me, which would have been 2002, concussions were really not looked at as a as a major problem. They didn't have concussion protocol. They didn't have a neurologist in the box who was to observe both teams. An unbiased opinion on whether or not a player had a concussion and needed to be removed from the game. That was, we weren't even close to that, and so, oftentimes not just myself, but players across the board would suffer a concussion. And what, you know, you know, player would be shaking his head, would come off on the sidelines, but oftentimes would go back in. And as I've learned, second impact syndrome is a terrible thing to have and can be, you know, completely debilitating. You have a concussion and you come out of the game. You shake it off. You get a couple smelling salts. You go back in the game and maybe you have another concussion. That could be, the long-term effects of that, we're still trying to decipher, but it's not good. And so what was and I and when I say a thousand or thousands of concussions and here is where I got this. It's not, it's not anything that I made up. So, I'm talking to Benjamin Omalu. Will Smith portrayed him in the movie “Concussion.”

Christina Brown Fisher:

Doctor Bennet Omalu, he is the forensic pathologist who identified chronic traumatic encephalopathy in Mike Webster. CTE is a degenerative disease, that is linked to repeated hits to the head, but it can only be identified postmortem. So, you're talking to Doctor Bennet Omalu? Approximately when?

Brett Favre:

I'm going to say, probably within the first three years after I retire. So, it would have been 2012 to '15, maybe.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay.

Brett Favre:

We, and I can't remember exactly what we were on, it was a, it was a conference call that, there was a lot of people on this call, and we were talking about concussions and the effect, and, you know, he has a different perspective. And I think his perspective is a great perspective, and here's why, he has no dog in the hunt. He's not a football fan. I say he's not a football fan. I mean, he, he doesn't know football from soccer or basketball, and quite frankly, he doesn't care. You know, and he on this conference call, there was a lot of questions, and I can't again, I can't remember exactly what it was in regards to, but after the conference call, he and I spoke and he asked me the question, “how many concussions have you had?” And so, I thought about it for a second and I said three.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Diagnosed concussions?

Brett Favre:

Diagnosed concussion or self-diagnosed.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay.

Brett Favre:

Where I blacked out or was, you know, I didn't remember, you know, what had happened, you know whatever. And he said, "okay, let me ask you a question," and I said, "okay." He said, "how many times did you get tackled or hit, whatever, and, and you saw stars, or you had, what seemed like flashes of light or fireworks or a little wooziness, and, you know, got up, shook your head, you know, anything like that?" And I said, "maybe, every time I hit my head on the turf or with a hard tackle," I said, "pretty much every time."

Brett Favre:

And he said, "that's a concussion, Brett," and I went, "that, that's a concussion." He said, "so you played 20 years, you played in 321 straight games, and you're saying that at least once, you could probably, easily say that it happened in the game. Your head hit the turf, you had ringing in your ears, you got up and you played. No one ever thought anything of it, including yourself." He said, "Brett, that's a concussion." He said, "think about boxing. We think of a knockout blow," he said, "but what about all the jabs that a boxer takes?" And he said, "I'll give you a good, good example of the greatest boxer ever, Muhammad Ali. You could probably count on one hand the times that he was really hit and knock and was knocked down or seemingly was hurt," and he said, "you know, like any boxer, you get jabbed a bunch, and he said, "you know, look, look at him the latter part of his life. The debilitating effects of the repeated blows," he said not the knockout blows, but the many hits, if you will, or the jabs took the toll. And he said, "in your case, I'm going to go out on a limb and say, you've had thousands of those ringing in the ears, fireworks, wooziness, but yet played.” And he said, "Those are all concussions, and that's where the damage is done." And after that phone call, I looked at, you know, concussions in the game much different because I didn't think that they were concussions. And the thing about concussions is, especially when you're 25 or 30 we all think that we're bulletproof. And you go, "well, I had it when I was 25 and I'm over it now," and, and then talking to Dr. Omalu and other doctors, the fear is what, what does it do at 55? What does the injury or the concussion or the wooziness, whatever at 25, when you think that you're over it the next day, and maybe you are the lasting effects down the road. As we see with a lot of NFL players, some have killed themselves, some have lived it, Mike Webster was living in his car. He was a Hall of Famer. Can't function in society, you know, at this, at this point in my life, I feel pretty good, mentally. You know, I don't have headaches or, you know, I would say I have some memory issues, but, I mean, I can't say that at 54, I'm any different than most 54. I, you know, I feel blessed.

Christina Brown Fisher:

How do you think the impact of concussion, repeated concussions, shows up in your life today?

Brett Favre:

That's the thing, is that at this point and that by no means am I, you know, striking up the band and celebrating, but I think at 54, I would say that mentally and cognitively, my memory, all the, you know, the mental effects are no different than a normal 54-year-old who has not played football or had repeated blows to the head because I've had my share and trust me, where I didn't really show any concern or care at 35 about what life would be like at 55, 60, 65, you know, you're just happy to be there, you know, at a younger age and you think, "well, I'll be fine." At this point in my life, there's a fear of what's to come. And, especially the fact that a lot has been, even though we don't know a lot about concussions, we know that they're not good long term. And it's my very last play as an NFL player, was a major concussion.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Yeah, I do want to get to that that game with the Vikings. Actually, what I want to do is I want to start from the beginning because, you know, when we talk about your 20 year career in the NFL, it you know, we're not talking about your career at, Southern Miss and high school or …

Brett Favre:

… or high school.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Or elementary school. So let's start from the beginning. My understanding, I read that you got your first football uniform at the age of one. Is that right?

Brett Favre:

Probably, so obviously at one I don't remember. It's what I've been told from what I've seen, but on pictures or, you know, childhood videos and stuff, but I was destined to play football or baseball. I grew up with two brothers and a sister. My dad was a high school football coach for 35 years. My mom was a special education teacher at the same school. It was a first through 12th school. So, my first-grade class and my 12th grade classes were all 100 yards apart, and as far back as I can remember, which may be, four, three, four, five-years-old I'm not sure, I was running balls in for my dad. Always around the high school players and that's all I knew, and then in the summer, my dad coached baseball. So, we transitioned over to the baseball, and I had two goals in life. Fortunately, I didn't have to fall back on a plan C. It was, I tried to play Major League Baseball or NFL football.

Christina Brown Fisher:

And it wasn't necessarily quarterback.

Brett Favre:

Not necessarily, I just wanted to play, and my first love was baseball, and the, and the, the sport that I felt like I was better at when I graduated high school was baseball. So, but I didn't really care, whichever one gave me the opportunity, I was okay with it. And, you know, at the dinner table we talked football or baseball depending on what, what time of year it was. And, you know that this is back in an era when there was no travel ball like there is now. And so, you didn't play baseball year-round? There's never been travel football, and you can only play football for so long because of the physical, physical aspect. But that's, you know, that's what I, that's all I knew. And my, my two brothers both had scholarships and played college football as well. And again, it was, you know, it's all we knew. And so I have zero idea, if I had concussions as a high school player or a junior high player, or in even elementary, because this is back the first time I played an actual game of football, I was in the fifth grade and it was pads. It was tackle. And honestly, I'm sure I suffered a concussion and never knew it, nor did anyone else for that matter. You know, this is back in the late 70s, and, you know, you got to believe that there were concussions daily, whether it be me or the teammate beside me or the opponent that we're playing concussions were, you know, we're a big part of it. And they were overlooked because no one knew, you know a kid shaking his head out there was having a concussion. So, you know, this goes way back. And that's the thing about Dr. Omalu. I asked him another question. I said, "so when's a good time to play tackle football?" And he laughed and he said, "never." And I said, "what do you mean, never?" He said, "the human brain in the human head is not built for tackle football." And he said, "I'm going to give you a couple of examples that you may find strange," he said, "the first a woodpecker," and I'm thinking, "where's he going with this?" And he said, "a woodpecker, what does it do? It sits there and bangs on a tree or a pole continuously without a concussion. Why? Because its skull and brain is built that when the woodpecker hits the pole or the tree, in our case, the brain will keep going, the head stops. Then there's an impact with the brain and then bruising, where a woodpecker has, he said, "for lack of a better term, it's got like Styrofoam around the brain and so when that, when that woodpecker hits a pole or tree, the brain does not continue to go and slosh around like a human brain," he said, "so you can," he said, "you could say that a ram, a muskox, animals that use their head as a, you know, a ramming mechanism, their, their skulls and, and brain, when the head stops, the brain stops." And he said, "the human brain and skull, on the other hand, regardless of age, when the head stops, when you hit the turf, the brain continues to move and sloshes around and impacts the, you know, the outer edge of the skull and that's when bruising happens,” which is what a concussion is. There's inflammation of the brain. And he said, "so you can wear the best helmets imaginable," and this made a lot of sense to me. He said, "you're not going to stop the brain from moving," and he said, "That's the problem, you may, you know, you got more cushion in the in the helmet. And it's in some respects its helps from the impact, but it doesn't stop the brain from moving." And so now I hear, you know, oh, "they got revolutionize the helmet off stuff," and he said, "when you fall and hit the turf with a new helmet the brain continues to move and it impacts the skull and trauma happens," and he said, "no helmet's going to stop that."

Christina Brown Fisher:

Do you think, though, that your 20, 21-year-old self, during this rookie season with the Falcons, playing for a coach that doesn't necessarily want you would have cared having heard this? Do you think that that would have, stopped you from asserting yourself as the player who should be starting the team?

Brett Favre:

Yes and no. I think, at 21, you know, it's been a long time, but I think at 21, I had it a lot figured out, and of course, I had nothing figured out, quite frankly. But if someone would have said, "Brett, I love your physicality. I love the way you play reckless and, and all this, but I just want, I just want to tell you you need to play, you can play reckless, you can play tough, but I want you to think about something. You may be fine now, but at 55 you may, you may affect your body by what you do, decision wise of how you play now. You may affect your body as you know, just from a physical, ankle, you know back, knees, hips, but physically, mentally. You need to be cautious of how you play." So slide, don't try to run over guys. You know which is, which is, which is not smart anyway because they're much bigger. They're much stronger they're...

Christina Brown Fisher:

So that was something that you would do?

Brett Favre:

I think I would yeah I think I would be wiser in, you know, live for another day, an extra yard, it's not going to win or lose this game unless it's the end of the game, and you need one more yard, and it's, you got to do all you can do. Then by all means, play the way that you need to play, but in general terms, don't be, you know, the tough guy, because it makes, you know, it may do some permanent damage down the road. Maybe not now, but at 55 you may say, "you know, I wish I'd listened to, to that advice.” I think I would have played differently then.

Christina Brown Fisher:

I want to get back to your early days of football, particularly playing for your dad. I’m wondering if there were any conversations about how to play the game more safely from your dad? I’m wondering if there were any conversations about how to play the game more safely from your dad?

Brett Favre:

No, you know it was a different era. And it my dad was old school and you know, he, he was the hard ass, and he was, as I've said, he was, he was short on "attaboys" or "good job." When I say short none come to mind anytime where he said, "Son, great game. I'm proud of you."

Christina Brown Fisher:

Even when you won? Even when you're the game-winning quarterback?

Brett Favre:

When, when I played my best or we won a game, it was worse. It, and, I think, and I don't know this for certain, my father passed away at 56. So, I don't know the answer to this, but I think I do. I think it, in his mind, again, it's a different era. In his mind and I'm only speculating, I believe, and I would be shocked if I were wrong, but I think he believed had he given me or anyone else breaks that it would go to my head and affect my future play, and that's understandable. I mean, you know, I can see where I would think that too, with whether it be my own kids or coaching, the kids I'm coaching, that, you don't know, if you're going to affect them negatively by giving them too much praise. But I think there's a happy medium that my dad never had. I mean, it was, you know, "alright, you had a good game, but it can always be better." You know, that was about as close to praise as he gave me. And I was okay with it, and I think my two brothers, maybe not so much. Because they, they seemed to be, and this is retrospectively. You know, me and my brothers get along great, but they kind of had an adverse reaction to how dad coached and, and raised. Where me the, the tougher he was on me, the more I dug my heels in. And, and I'll give you an example. You know, he, he may be chewing my butt at practice, and it may be something I didn't do. Well, my reaction to that would be I would go run ten stadiums and like I'll show you. Rather than, well hell, I'll, um, you know, I'll quit practice and go home. You know, I was more digging my heels in and I would say, "okay, I'm gonna do 50 more push-ups. I'll show you."

Christina Brown Fisher:

When you talk about your real awareness of concussion and its impact and role on your career, it, it really doesn't come to you until after you've retired. Right?

Brett Favre:

Right, the end.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Yeah, after you've had this conversation with Dr. Omalu. And yet we know that you clearly suffered at least a few diagnosed concussions. I mean, we can talk about your last game. Well, let, let us, let us talk about your last play, your last game, with the Vikings. What happened there, and what role did that play in your decision to leave the game?

Brett Favre:

So, we're playing the, it was kind of weird because, it's my 20th year, and the previous year we had, I had the best year, statistically speaking, of my entire career, was my first year with Minnesota, my 19th year. We were virtually a play away from the Super Bowl, and, we didn't, we didn't get there, but we had a great year. So everyone was like, "surely next year we will, you know. You know, we'll get there.” And so. I would say a large part of me did not want to play in my last year. Which was my 20th.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay, why, what was it about this year?

Brett Favre:

There were two things, really. Physically, for the first time in my career. I didn't feel up to the challenge, physically. Everything hurt. And you know what, you know what little nitpicking injuries if you want to call them that, early in my career, or throughout my career, I would, I would, as I said earlier, by Wednesday or Thursday I was over 'em, you know, and it was like on to the next game. Whereas after year 19 or through that season of, of 19, my 19th year, I didn't recover. You know, when I, I, when I just started to feel like I was turning the corner, we were playing again. And so it was, it was tough to muster up the energy each and every day to, to do what, you know much is asked of a quarterback. And, you know, the older you get, you look at things and I played a long time. So, I looked at things in the latter part of my career, much like a coach would. So, I would, I would take the losses a lot harder than I did early in my career, as you would expect a 21-year-old kid. You lose a game by the time you get, say it's an away game. By the time the flight lands back in your town, you're, you're over it. You know, you're 21 and you're like, “hey, we play next week.”

Christina Brown Fisher:

You're looking ahead to the next game.

Brett Favre:

Yeah, where at 38, 39, I never got over the losses. And I, when I think back on my career I think about the losses or the, the plays or the games where we almost, you know, did something great, or almost won the game, rather than the good things that I've done in the, in the games we won, and the wonderful seasons we've had. So you know here I am in year 19, and we come basically to a play away from the Super Bowl. Great year, statistically speaking, my greatest year in 20-years. At the end of that year, it was a devastating loss. It was a wonderful year. I mean, I enjoyed my teammates, I enjoyed playing, but I thought to myself, "the chances of reproducing that," even though from the outside looking in, all the experts, all the fans. And I understand this would say, “you're so close. Next year you're going. You're, I mean, you're there's no question you come back. It's going to be an even better year." You know, I could see that. I could see why people would say that. But I, on the other hand was thinking, "I don't know." You know, it's, professional football is very difficult to succeed, over and over again. And. and I get that, and, you know, I've had a wonderful career up to the end. You know, if I, if I, as I think back, if there's one thing, I wish would have happened more than it happened would be that we won more Super Bowls. But but all in all, you know my 20-years was a win was a big win.

Christina Brown Fisher:

What do you remember about that game, that last game of yours?

Brett Favre:

It was colder than hell. What I remember was that the Metrodome collapsed under, you know, a large amount of snow. And so, we're, we're scheduled to play a Monday night game in Minnesota against the Chicago Bears. You know, when they made that schedule that at the start of that year, they thought this would be a high-profile game. Turns out, take the, take Dome collapse out of it, turns out it was a, you know, it was a throw away game. What I mean by that was we were not any good, nor were the Chicago Bears. The game had no implications other than for Viking fans or for Bear fans. You know, for, you know, for bragging rights. So, it really meant nothing. I think we had four wins at the end of that year, and I had about three or four. But so that game really meant nothing. Then the Dome collapses. So, you know, I remember fans saying, what else? You know what else can happen? So, they ended up not canceling the game. They later in turn, we played it at the University of Minnesota. Their season had been long over, so the field had basically been snowed over. It's an out, outdoor stadium, and they scraped as much snow and ice as they could off the field and got it ready to play for a Monday night game. And, you know, I played in the game, and it was, I don't know, it wasn't the coldest game I've ever played in, but it certainly was cold, you know. And, somewhere, I think in the second quarter, I believe was the second quarter. The game, I mean, it was, you know, it, it was a nail biter at that point, but I threw a routine pass to the left. And you know one I'd thrown my whole career, and I dump it off to my guy, and I'm watching him catch it. And soon as he turns to run, I get pushed. I don't get hit, I get pushed and I slip on ice, you know understandably so. And I remember now this came back to me later I didn't remember initially but I remember going like it was like slow motion. I'm falling watching my guy run with the ball and my head hits, the artificial turf, but it was really like a hockey rink being honest with you. It was the ice. So my head hits the turf and the lights go out. And our trainer, a guy Eric Sugarman, we call him "Shug." The next thing I remember was him, "Hey, buddy. Wake up! Hey, buddy." And as I remember waking up I remember snoring, and I said, "What's going on?" And he said, and I remember asking. I looked over and I saw, like, Brian Urlacher and a couple of other Bear players kind of clapping, and I asked, "Shug, what are the Bears doing here?" And he kind of laughed and he said, "hey, buddy, you had a concussion. Let's go to the locker room." So, I got up and walked to the sidelines, you know, people clapping and cheered. I felt fine. I mean, there was I wasn't hurting, there was no headaches.

Christina Brown Fisher:

No, no stars? No…

Brett Favre:

It was just a little ...

Christina Brown Fisher:

No fogginess?

Brett Favre: You know, it didn't make sense, everything didn't make sense. I really didn't know what was going on. I wasn't cold at that point. I remember that vividly because I'd been freezing up to that point. And it was kind of like, "What am I doing here? How did I get here? Everybody seems to be freezing, but yet I'm warm."

Christina Brown Fisher:

Wow.

Brett Favre:

And we walk straight to the locker room. I got a hot shower. I got a hot dog, and a cup, of, or, a paper cup of hot apple cider. I will never forget. And I got my street clothes on, and Shug said, "How are you doing?" I said, by this time, you know, the fog had lifted, and I said, "I know one thing, Shug, it's over." And he said, "what are you talking about?" And I said, "I'm not, I'm never playing again." And I never looked back from that point. I knew.

Christina Brown Fisher:

And that was definitive? Because you you had retired before …

Brett Favre:

I'd retired twice. And this time there was no question. And there was no question for one reason. By this time, after the shower and, you know, putting on my street clothes, I realized what had happened. And I just remember thinking to myself, "There's never a good time to have a major concussion. Certainly not at 40 and if there was ever writing on the wall, this is it." And I retired and never once from that point did I go, "you know I probably could still play another year, or," I just, I knew for a lot of reasons, but more than anything, a major concussion. Because at this point, if you think back 2010, you know, that's when really the NFL took more of an initiative to you know you're not going to get rid of concussions. You're not going to take them away from the game. But you're but you're, this is when they had concussion protocol, and everyone did a baseline test. And they had a neurologist.

Christina Brown Fisher:

By the time the NFL concussion protocols are in place, you are …

Brett Favre:

I'm damaged. I'm damaged goods.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Yeah, you're more than 15 years into your career with the NFL.

Brett Favre:

Yeah, my baseline is skewed tremendously. You know, a player just starting out does a baseline, different story. So, my baseline is you know after no telling how many concussions, you know, minor, major, regardless.

Christina Brown Fisher:

But how did the concussion protocols Brett change the dynamic or the culture around brain injury? I mean we have no problem talking about Aaron Rodgers torn ACL. We have no problem talking about various orthopedic injuries. How do the protocols change, how we discuss or how the players, discuss and are open to some degree about the impact of brain injury?

Brett Favre:

You know, I don't know if players, you know that's the thing about NFL players, I, I don't, I would be shocked in today's game that if you were to hide a camera in the locker room or in meeting rooms or in a place where the players congregate and talk, that there would ever be talk of concussions and the repercussions that they may have on their life after. That you would think that there would be more, you know, like, "Hey, we, we need to be more careful. We need to be, you know, the league maybe acting like they're taking precautions from, from a concussion perspective and that they have our best interests in mind." But let's be real. It's about the dollar and maybe, you know, their talk of baseline concussion protocol, having a neurologist, an unbiased neurologist on side at every game that can remove a player from the game at any point based on what they see. That, that, that, you know, that they're looking out for us. You would think a player would say, "well, let's be real. You know, we have to look out for us." Because if we don't trust me, you know, we're, we're, we're basically, you know, we're just a number. And if you can perform and, and up the ratings for the NFL, that neurologist is not going to take you out of the game, or if it's a Super Bowl, and Tom Brady, or Aaron Rodgers, or Patrick Mahomes or any, any player with a high value, gets tackled and shakes his head, you think that neurologist is going to pull that player out of the game?

Christina Brown Fisher:

You don't believe that they're truly as independent as we are being led to believe.

Brett Favre:

No, no. You know, I think, I think in regards to concussions, they're doing more. But I think most of that is because, they almost have to. They have to show that, you know, they're willing to, to fight concussions and do bigger and better things and more protecting the players. And I do think to a certain degree, the NFL feels obligated to protect the players. I do think that they have the best interests at mind, but I do believe, the most important thing for the NFL is money and ratings. And it's a business, I mean, make no mistake about it, it's a business. And, you know, I'm not, I'm not saying that they should have done better for my health care. I'm not saying that. I think ultimately the player has to decide. You know, there was a lot of times that I easily could have said, "I can't play this week," and not even, not even talking about concussions. I broke my thumb on my throwing hand. You would think you break your thumb on your throwing hand. It'd be like a sprinter breaks a toe, and, but yet goes out and runs the 100-meter, meter, you know dash. When that player or that person easily could say, "I can't run, I got a broken toe. I can't throw, I got a broken thumb." But yet I chose to play. But that choice, you know, ultimately was my choice. So, I chose to play. And so, you know, I think ultimately the player has to, you know, a trainer can say, "I don't think you're able to play this week." The player can say, "why." You know, the coach ultimately can say, "I'm not playing.” But in my case, I would always say I tore a knee ligament and, I wore a brace the next week, but I played, I played well, I broke my thumb, I played the next week, I played well, and after a while the coaches and the trainers were like, “crap, he plays better after he's hurt, so we're going to leave it up to him.” So, I think the player first and foremost, has to take the initiative on what they feel it's best for their body and if they choose to play and the team, allows them to play. I don't think you can. You can necessarily hold the team or 100% accountable for you know life after, you know, but in regards to concussions, that “concussion” is a bad word to the NFL. And you mentioned you can talk about Aaron Rodgers’ Achilles ‘til you're blue in the face and they have no problems with it. But had Aaron Rodgers suffered a major concussion on that play rather than Achilles. I think we had a total different dialog after that. And, and it's going to be mostly other people talking about what the NFL is going to do, rather than the NFL voicing any opinion other than the initial statement. You know, we're monitoring and we're in he's in concussion protocol. We'll get back with you like, that's it.

Christina Brown Fisher:

And it seems like you don't have the same amount of, grace, if you will, when you're talking head injury versus a different type of physical injury.

Brett Favre:

You're you're 100% correct. You know, the concussion again, is, is a is taboo for the league. You know, they're saying, "well, we have better helmets. We, we've we entered into, an agreement with this company, and they had bigger and better helmets, there's more cushion, the helmets are bigger, blah, blah, blah. Therefore, concussions will be the less". They are, to my knowledge, concussions have not decreased. Because here's the thing. And Dr, Omalu, said it clearly. He said, "I bet your concussions, your major concussions, were when you hit the turf." and I was like, "how did you know that?" And he goes, "every time you hit the turf, you get knocked down, you get tripped, whatever. You don't even have to have a big blow. You hit the turf, the whiplash effect is one of the," you know, an elderly woman, elderly man, or child slips on the sidewalk, hits their head on the ground. You got to believe that there's going to be a concussion that takes place there. Absolutely, with or without a helmet. The helmet, think about it. The helmet will cushion you against concrete. You know, maybe you don't have a scrape. Maybe you don't have an external injury. But it doesn't do anything for stopping the brain. Going back to what we talked about earlier. And when Dr. Omalu explained, you know how the head works in certain animals versus the human, it made perfect sense to me. And I'm not the smartest guy out there, but I, but I get that the brain continues to move, the head start. And therefore, when the head or the brain hits something. The skull, in this case bruising it, you know, and I'm sure there's a much more detailed description of what a concussion really is.

Christina Brown Fisher:

How does the concussion show up for you? Is it memory loss? Is it inability to focus? Is it multitasking? How have you seen it impact your life.

Brett Favre:

Well, you know, all of the above. But again, it's hard to, I think the better way to explain it for me would have been after the concussion, maybe a three day window or a four day window after that concussion where I remember having won against the New York Giants in Green Bay, where I was, I was not, pushed over a guy, and I fell on my back and my head hit the turf. And I'll never forget I didn't remember this at the time, but when the fog lifted and a day or two later when everything kind of came back to me, I remember hitting the turf and having a, it was like the loudest noise in my ears. And it was like, you know, I was cringing like, you know, there was a ringing in my and I, I don't know if I looked like this, but I felt like I was just, you know, like just that noise out of my ears. I went out of the game for a play. And I didn't know this at the time, but I was talking to our doctors, and I ran back in the game, and it was fourth down. I had no clue it was fourth down. I ran a play, and I threw a touchdown like 30 yards. And we ended up winning the game and the doctors couldn't stop me before I got back on the field. A threw touchdown pass came out of the game cause defense was on the field, and I never played again the rest of the game. It may have been a quarter and a half. I was sitting on an ice chest, and you know they would, "How are you doing? I'm fine. I can go back in and play. You're not going back in." And I didn't go back in. And so, I'll never forget after the game. Me and my agent, we went and played golf at the local golf course there in Green Bay, and I played my best round of golf ever and the day after the golf, so the Monday after the game. Like everything it was real clear to me then, and I, and my agent was joking like, "you need to get a concussion more often. You played your best round the golf," and I was like, "we played golf?" You know, so that's kind of what it, but, but all this was kind of after the fact. I look back and I go,

Christina Brown Fisher:

So, you didn't even remember?

Brett Favre:

No, no, I didn't remember until several days later. Like stuff was kind of coming back to me in pieces.

Christina Brown Fisher:

When you realize that you're not remembering things, what does that do to you emotionally? Do you brush it off or are you worried at all?

Brett Favre:

Well, the you know, the Giants, concussion was probably around my 10th year. So, around my 10th year, I'm 32, 33, 31. I think it was, it was brushed off. I mean, I, you know, it's been a long time, but I, I would, knowing me at that time I was like. Once I started, you know, getting my faculties back. So, say Tuesday, maybe Wednesday, when everything kind of is like, "oh, okay," I played golf, I threw a touchdown pass. And, you know, I ran back in the game. All this kind of was now clear to me. I was like, you know, and it's easy to see why I felt this way. Wednesday, everything's clear. I remember everything. So, you think you're fine? You're back to normal. So why would you think "what's this doing to me at 55?" So I brushed it off. Fast forward to the last play of my career. Different perspective as I, as the dust kinda settles and the fog is lifted, and things are starting to become clear. I go, "This ain't good." You know, there's never a good time to have a major concussion, you know? But certainly not at 40, and quite frankly, not as twelve. Yeah. You know, but it was much clearer. And I knew at that point that.

Christina Brown Fisher: So, it's, it's it's also maturity. It's, it's time in career and also what you had accomplished in your career. You had accomplished so much in your career that I'm assuming you didn't feel like there was anything more that you felt like you needed to prove.

Brett Favre:

No, I mean, I, I was, you know, I thought when I went back that last year, I thought it's worth a shot. We had we came so close. My teammates wanted me back, that, those things were very positive things and had an impact on me returning. The fact that my teammates wanted me back was probably more than anything the determining factor, of me coming back to play. They were like, "come on Brett." I mean, we were so close, you know? You know, the low little voice in the back of my head, I was like, "Brett, yeah, there is a chance. You know, you can easily go back, but you could easily not. And how will you accept if you have a down year?" And kind of in a, you know, forgetful year. And you know and then that little voice says "well, that ain't gonna happen." But you know, when I had the season again, was, it was, was a wash. It was, it was not good. And then I had this concussion. It was like, okay, if there was ever a sign, you know...

Christina Brown Fisher:

Now's the time.

Brett Favre:

And I look back, you know, I told people this many times, I said, you know, I've had a lot of people say, "well, you know, that last year was not a good year. I bet you wish you wouldn't have played," and I go, "Wrong, I'm glad I played for no other reason, but for the fact that it told me that, that, you know, the writing was on the wall and and it was not to be." And had I not played that last year and sat at home, I would always wonder "what would have happened had I gone back for my 20th year. We probably would have gone to the Super Bowl.” I've had all those thoughts, and it would have drove me crazy, but now I know. And, and I'm, I'm thankful for that clear, easy decision that it wasn't to be and least you know now.

Christina Brown Fisher:

I want to talk a little bit about kind of where we are, you know, football is so embedded in American culture, and yet we are at a place where we have a lot of people, including lawmakers, talking about the future of football in really ominous terms. What are your thoughts in light of the prevalence of head injury, in light of what we discussed with regards to how you protect players? What are your thoughts on what the dialog should be like in terms of the future of football?

Brett Favre:

Well, now I go back to what Dr. Omalu said, "there's no good time to play tackle football," but we're not going, you know, you know this, I know this. Anybody with any sense in America knows that football will always be tackle. They will never put flags on professional players. You know, it just, it's you're right, it's you know American football in America is, you know, is a culture all in itself and people live by it, and that's not going to change. I do think, I'll say this, I wish a lot of the rule changes that they have now in regards to protecting players were in place when I played, because they would have protected me against myself. Quarterbacks nowadays do not get hit. If they even get close to being hit, a flag is thrown, and it has really changed the game. I hear this from a lot of people. Imagine what you could have done with the rule changes and the fact that, you know, they couldn't cheap shot you, and they couldn't. You know, all the things that that were important that were in place in regards to not protecting players then, took a toll on me and a lot of players. But these rule changes and I hear this a lot from people, "It ain't the same. I don't like watching I mean, these quarterbacks and pansies," and and all this stuff. I don't necessarily agree with that because I think. You know, there's a lot of tough quarterbacks out there. There's a lot of tough players out there, but they can't it's not their fault that the rule changes have, have, had, you know, position them to not get hit. You know, great for them, bad for me. But it is what it is. And so, I do think that those rule changes in regards to the quarterbacks are great for the longevity of the quarterback because the bottom line is money and ratings. And if the starting quarterbacks were out of the games, maybe people are less likely to watch. I don't know. You know, I mean, you. I mean, that's the, you know, the obvious reason to protect them. The League may say, well, we just want to protect the player for their, their own safety and for their longevity after football and maybe there's a percentage of that, that is true. But it's you know, it's we want our guy in the game the NFL, the face of the NFL is Patrick Mahomes or Josh Allen or Lamar Jackson. You know, you go down the list. We want them in the game, and whatever we got to do to keep them in the game, even if it's you can't even look at them funny or we're going to throw a flag. I mean that's the way it seems this today, and you know, I laugh at, you know, I'm like, all bets were off with me. They were like, "hey, throw the wolves to Farve," you know? And I think part of that, was the way I played. You know, I mean, I would, you know, throw my body. You know, I would fight, I would, you know, I would have trash talk with players and, and, and so you kind of, or ref, or call from a penalty perspective based on how you play. So maybe, maybe in some respects I brought that on myself. But, you know, it would have been nice to have those rule changes when I was playing. Because it would have protected me from myself.

Christina Brown Fisher:

What do you tell people, who, I'm sure you get this question. I know you have two daughters, but you have grandsons. What do you tell people when they ask you, would you let your grandsons play football?

Brett Favre:

Well, I would let 'em play because…

Christina Brown Fisher:

At what age?

Brett Favre:

I'm glad. I'm glad you asked that. Because my oldest grandson's 13. He'll be a ninth grader next year, which I can't believe. The second is nine and the third is six. None of them play football. None of them have ever, the oldest has asked me questions in regards to football, and I'll give you an example. I'm driving him to school one day. This is probably 3 or 4 years ago, so he's in eighth grade now. His name's Parker, bright young man, plays soccer.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Which has its own concussion issues.

Brett Favre:

Correct, well, you know, I suppose a little bit safer, you know? He wants to play soccer. I don't know anything about soccer, but I'm happy for him. So I'm driving him school one day, and he, they call me "Pawpaw," so he says, "Pawpaw, do you know Drew Brees?" And I was like, "Yeah," and he's like, "man, that's cool," and I was like, “okay yeah,” and I had a chuckle about it, well, but he's kind of, inquisitive. He's at that point where you know, him and his buddies talk about it and all that stuff, and so he's asking me questions. But that's about as far as the three combined have gone in regards to football. They have never once mentioned to me, should I play football or would you like to see me play football or, "Pawpaw, I'm thinking about playing football. What do you think?" Never has it come up and I will never bring it up to them unless they bring it up to me. And what I mean by that is I will never entice them to play football. I'll support 'em. If they want to play, I'll support them. But you know the chances of any young…

Christina Brown Fisher:

You would support them after what you endured, not only as a professional, but even in high school?

Brett Favre:

Yeah, if Parker says, "Pawpaw, I'm thinking about playing football." I would say, "okay, buddy what are you thinking", you know, "well, I think I'm going to go out next year and give it a shot." You know, I don't think it's my place to say I don't think you should do that.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay.

Brett Favre:

But I think my place is to support them whichever way, but not to entice them. So I'm never going to say, "I know you play," the second one plays baseball and soccer, and he's good in both, and he loves both. I mean, he, he can’t, he can't hit enough baseballs. They can't kick enough, and their dad is from England so he's a soccer guy. But you know I, I just don't, I don't, I would feel terrible and guilty if I said, "Well you need to give football a try," and then they go out and have a concussion. Then I feel horrible. I would feel horrible if they went out and played anyway on their own behalf and had a concussion and you know God forbid something happened later down the road that's related to that. I just know that it's very hard for any I don't care how athletic a 12-year-old kid is, the chances of that kid, I don't care who he is, the chances that kid ever making it to professional football and having the success that I had, or any other professional football players had; the chances of that happening are slim and none. Then I take into account what are the chances of, let's just use Parker as an example, him playing college football. Being a starter having all these expectations based on him being my grandson, and that's not fair. And, you know, I think more harm maybe would happen than good in the long run because of that, you know, or "you never could live up to what your grandpa." I don't want them to endure that. Play soccer, play baseball, play golf. Yeah, whatever, I'll caddy for you. You know, I'll do whatever, but I love him to death, and I feel like my place is to support him, but not entice him.

Christina Brown Fisher:

I understand that you have been coaching though, or you have coached the high school…

Brett Favre:

For two years after after I retired…

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay, so when did you coach and what was the age group you were coaching?

Brett Favre:

It was high school, and it was, so I retired, I think it was, I always do this…

Christina Brown Fisher:

2011?

Brett Favre:

2011.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Yeah.

Brett Favre:

So the first year out of retirement, I did nothing. So, '12, I just was riding away just enjoying life. The head coach at the local high school I've known for a long time and he's a great coach and he's been super successful, and it's where my two daughters graduated high school and it's where I worked out every offseason. I would actually work out with the kids. We'd run sprints together, I'd throw routes with them, and, and it was really refreshing for me. Well, he would always, the head coach, would always say right before I went back to play, "now when you retire Brett, you got to promise me one thing, you'll be my offensive coordinator." And his name is Neville, that's his first name, Neville. So, I would say, "Neville, deal." Thinking you know, "that'll never happen." I mean, but I'm just, I'm just appeasing him. So, I would say, "yeah, I'll do it." So, I retire, the first year I said, "Neville, not right now. I just want to take a break." He said, "I get it." So, the second year he wouldn't leave me alone. And I said, "okay, I'll be your offensive coordinator," and he said, "now look, I can only pay you $3,500." I said, "Neville, I don't want the money, I'm going, gonna do this as a favor to you." And I'll be honest with you. I really didn't think I had any juice left in the tank to really make a difference for these young men.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Why do you say that?

Brett Favre:

Well, I'll just say I was exhausted mentally. You know, I played football had been all I knew as far back as I can remember, going back to three or 4-years-old, from what I can remember, and my hopes and my dreams and my expectations were all to play pro football. And I, and I, was able to achieve that at, at unbelievable levels. And to play 20-years to start 321 straight games is exhausting and I'm not even talking about the physical part of it. Now coaching there's not a whole lot physical that's involved, but I was thinking mentally, "I just don't, you know, do I want to deal with it. Do I want to have to teach these kids how to run routes," and, and, you know, you know, they're high school kids. That's great, they're unaffected by what's, the money, and the fame and all that stuff, that's great, but they're raw. Do I have the patience to teach 'em over and over and over again without losing my cool. So, I, I really didn't know. But I'll be honest with you, I coached two years the first year we had a decent year. All the kids basically were back the second year, and I loved them, and we won the state championship. And, and, and I'll tell you, there were a couple. There were more than a couple, but a couple of incidences that I always tell people there were, there were a couple of young kids that I would teach these routes and plays and stuff to these kids and a couple of these guys were not startered, but they would run the route and they'd run it wrong, but they were trying. And I remember one kid, his name was Darius, and he would come back to me, and he'd say, "what do you think?" And it was it was not a good route, and I would say, "Darius, we got to do better." Look, and I will kind of walk through it. I obviously couldn't run the routes, but I would kind of walk through what I was looking for, and he would try, and it and it would not be good. And then one day we were in practice, and he ran the route. I'll never forget, he ran the route exactly like I coached him, and he the ball was thrown to him and he caught it, and I wish there would have been a camera. I went over and gave that kid the biggest hug and was, I was elated that he finally got it. But maybe more than that, as he if he knew he got it, and the, the, the joy on his face again he wasn't a starter, so he may not ever play. You would have thought he won the Super Bowl. And the, the feeling was really nothing that I'd ever felt before because I was in a different, you know, environment. I mean I was not the player. I was not the main focus. You know, I was just a coach, and you know, I've been in the Super Bowl, I've won MVPs, I played in Pro Bowls. You know I've played in big games and have unbelievable comeback. I had it all. And you would think that this particular incident would have been just, you know, just another, but it, was it was such a joy. And I realized then that I did have a lot of love and, juice left in the tank and really felt like I was making an impact on these young kids. Aside from the state championship, which was a great, to me, I remember when we got our rings, state championship rings, it wasn't a Super Bowl ring, but I really felt, I mean, there was a certain feeling that I'd never felt, even in pro football, that it's hard to explain. I was like, "This is something special. It's different, but it's something special." And I've had a lot of kids I've seen these kids. We were eating in a Mexican restaurant one night, and this, this one lineman that I coached, was a great kid, and he and his mom were in there eating, and he came over to me and he gave me a hug, and I gave him a hug, and he said, "Coach, so good to see you. I want you to know that you've had a big impact on my life." And his mom gave me a hug. She's crying, "she said you were so good to my son." And, I mean, I was in tears. And, you know, if I wondered what type of impact or what type of a coach I was, I didn't wonder anymore after, you know, encountering them after. And I'm sure there's probably players that say, well, "he didn't do anything for me." I tried, I tried my best and you know, and I after my second year and we won state championship and I said, "you know, I think I'm just gonna not coach anymore." Because it was exhausting, and it did take up some time. Not a great deal, but it took up some time. And by my youngest daughter was entering high school and was playing volleyball, and I wanted to be there for every game. And I was and I was thankful for that because had I coached high school football, volleyball was the same during the same time. And there was a good chance I would have missed half her games. And I'm like, I'll retired. Yeah, there's no excuse for me to miss a game.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Yeah, I, I read, I read that your parents made a point of going to all of your games …

Brett Favre:

Never missed a game.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Never missed a game. I wonder, Brett, I want to talk also about the downside, the dark side of football and and the toll that it took on you. There was a point in your career where you talked about developing into an addiction. To to painkillers. I want to talk a little bit about that to the degree that that you're comfortable when and how how did that start? And then what ultimately led you to recognize that you needed to stop?

Brett Favre:

Yeah, so, I remember vividly how it began. So, we're playing my first two years in green Bay, '92 and '93. We, we played three home games in Milwaukee and this, this and people to this day go, "Why were y’all playing games in Milwaukee?" Well, it was a deal that, I guess the Packers in Milwaukee had had going back before Vince Lombardi. Where five games were played in Lambeau Field and three were in Milwaukee. And they had done that forever. So my first two years, we played three games in Milwaukee, and my second year we put one of our games in Milwaukee was against Philadelphia Eagles and Reggie White was the defensive end. They had a, they had a great. I mean, I'm young, very young, but they had a very old defense. But they were, every player on their defense was like a star. And, you know, the biggest star was Reggie White. Well, right before halftime, we're running the play. We're running a low pass play to the right side, and Reggie was coming off that side, and Reggie broke free and I, I mean I'm looking at Reggie coming right at me, and I hurry up flick the pass real quick to the fullback and Reggie wraps me up and drops me on my left shoulder with all this weight on the top of me. And I had a third-degree separation on my shoulder, my left shoulder, it wasn't my throwing shoulder, and it was one of the more painful injuries I've had on the field. And um, I got up, now, keep in mind, I got my job a year and a half before, which was because the guy in front of me got hurt and I got a chance to play, and he never saw the field again. So, every injury that I had from that time I became a starter till the time I retired I always thought "if you if you come out of this game, you are giving the next guy a chance to play, and he may shine and they may forget you," that always. So, I said, "I'm staying in the game." Well, we had about four minutes before halftime, so I sucked it up. Played going into halftime. The doctor said "you got a third degree separation," which is as bad as it gets. And it was painful. We're going to inject it, if you if you want to play the second half, we will inject it. And I said, "hell yeah inject it," so they stuck a needle in it, and lo and behold it felt great. You know, I'm moving my shoulder around. I could feel stuff popping and crackling, but there was no pain. So, I play the second half, and I actually played great and we won the game. It was a big win. So, after the game, it was an hour and a half drive back to Green Bay. They gave me some pain pills. When the injection wore off all hell broke loose. It was a terrible pain. Everything I did, sneeze, it hurt like hell. You know, move any which way it hurt like hell. I mean, I was, like, frozen. I'll take these two pain pills. And the shoulder pain was gone, and I felt good. I kind of felt euphoric. So, from that point on, it slowly and I'm, and I'm not just talking about the shoulder any little nagging injury. I used as an excuse to get pain pills, if that makes sense. Not necessarily because it helped with that sprained ankle or it was, you know, third degree separation or thigh bruise. Maybe it helped with that, but it, I felt good, and I liked that feeling.

Christina Brown Fisher:

At the height of your addiction, how many pills approximately would you say you were taking?

Brett Favre:

I was taking 16 Vicodin ES every night.

Christina Brown Fisher:

16 Vicodin a day.

Brett Favre:

All at one time. So, I would gobble all 16, put them in my hand, put them in my mouth and swallow.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Who knew?

Brett Favre:

I thought no one, but I think everyone did, and certainly my wife knew because after the fact, later down the road, she told me, she said, "you know, I was flushing a lot of your pills down the toilet." And I was like, "had I known that at the time I would have been irate." I would have been a mad man. But the thing about addiction, and I'm sure you probably know a lot about it is that you think you're the only one that knows. You think that you've got it all figured out and you're, you're fine, and I certainly was, you know, no exception. But really and this, you know, this went on, I went to rehab in '96.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Talk about what triggered the rehab.

Brett Favre:

So I started taking the pain pills because of the, the shoulder. And slowly you know two pill wouldn't work. So, I had to go to three. And then at some point three pills wouldn't work and I'd have to go to four. You know, I don't know what the three-month four month window, whatever it was. But I would have to increase it, I could you know what, I would increase it and say I was at four pills and only had three and I would take three the next day, it would have no effect on me, none. So, I was always, it was easier to get four pills than it was 16, obviously. But I, you know, I was playing I never missed a game. Meanwhile, throughout this three-year window. So '93 to '96, slowly but surely, I was increasing and I think the latter part of '95, so the year before I went to rehab. Latter part of the year, we're playing Detroit, in Green Bay, and I'm at home the day before the game. We have family and friends in town. And I'm sitting on the couch, and I don't know how many pills I was up to at this point, but a lot. And next thing I know, I wake up and there's all these people staring at me, standing around. I'm laying on the couch and they're, they have a lot of fear like I've never seen, and I said, "what are y’all doing." They said, "you had a seizure." And I was like, "what do you mean, a seizure?" Like. I've heard of people having seizures, but, I mean, here I am 25 and in the prime of my life, I'd, I won one MVP and was getting ready to win the second. So, I'm playing great. You know, what's the big deal? So, our team doctor came over to the house and, you know, checked me out. Everyone's concerned. I never let on anything about pain pills or anything like that, you know? Question was, what happened? What triggered it? You know what's going on here? You know there's no reason for a healthy you know, athletic individual to have a seizure. So, I don't want to say it was forgotten, but it was filed away by everyone. And I again, I didn't offer any insight to what I was doing. And quite frankly, I don't think that I put two and two together at the time. I didn't I didn't relate anything to do with.

Christina Brown Fisher:

So, you’re. not making the connection between seizures and I mean, do you even recognize that you have an addiction?

Brett Favre:

I think at that point. I was getting to a point where I thought this ain't normal. Because at this point it really had, it started around this time, mid ‘95 season where it had consumed me, where all I thought about was getting and taking the pills, not, not playing and winning the game. That was important, but only important if I had the pills and I was, I was able to take 'em. You know, so long as that I was in control of everything. Long as the pills were in place, and I would take them at 9:00 every night. Why? I don't know, but that was the regiment, and I would stay up all night. So, at that point, I was like, I knew that lack of sleep was not good because I would. I would go usually to bed about 4:00 and stay up all night in the house, just wired like crazy. You know, a normal person would take pain pills that would, they would help with the pain, but they would put you to sleep? You get that sometimes you don't even like the effect of it, but it would, me, I, that's the only reason I was taking it, is, it gave me a euphoric feeling and I stayed up all night. I thought, you know, calling my buddies, playing on the computer and my wife is in bed asleep. Every once in a while, I should get up, "what are you doing? I'm studying my playbook." Yeah, I'm just wired, like and then about 4 or 5:00, I would go to sleep. Sleep an hour and a half, go to team meeting, and then we would break and go into position meetings. Then I would fall asleep.

Christina Brown Fisher:

And this all felt very normal to you?

Brett Favre:

Well, I was playing great, so that was the deception.

Christina Brown Fisher:

And that, I mean, and that's a that's at the heart of all of this. As long as you play and play well…

Brett Favre:

I mean, why would I be any different? Why would I change the routine? Because I'm playing great. I ended up winning three MVPs in a row and was in the height of my pain pill addiction. It makes absolutely no sense. But it was deceiving because I'm like, I'm not changing my routine and I can't play any better, you know? So, I mean, you can see where the person in, me, in this case will think “it's okay. I mean, yeah, I would like to have more sleep and feel better during the day, but crap, you know, I threw five touchdowns last week when we beat the Bears and we're leading in the division. So, heck, I'm not changing anything.” So, you know that was the deception part of it. So, you know it took, into after the '95 season that keep in mind. I had a seizure couple months prior to the end of the season. We made it to the playoffs. We go all the way to the championship game; we lose to the Cowboys and then it's off season. So, I end up having a routine ankle surgery in Green Bay. A scope on my ankle, which generally the next day you could go home. So, while I'm in hospital, my wife, our youngest daughter, was not born and usually you don't even stay overnight, but I stayed overnight. I got the pain pump. I'm using that, I'm going to stay in there as long as they can keep the pain pump on me and it's routine ankle surgery. You don't even need a pain pump. But I'm like, "ah, the pain is terrible." So I stay an extra night. I'm pain pumping like crazy. My oldest daughter and my wife were in the room. We're chatting and the next thing I know, all these doctors are standing around staring at me. And I'm like, "what are y'all doing?" They said, "you had a seizure." So, I had number two within a couple months of each other. Now the radar was up on a lot of people. Like this ain't normal, this ain't right. We got to figure it out. So, I met with the neurologist. And he dug deep, and he dug deep and dug deep. And eventually I came clean and said, "well, I've been taking pain pills, and I don't sleep." And he said, "he said, the lack of sleep is short circuited your brain." For a lack of a better term the body needs sleep and you're, you know, you're hustling and going on and wide open and you're sleeping you know maybe an hour of good sleep maybe. A night or a day whatever you want to call it and basically you brain is in short circuit. And so, this was, you know, late February, March of '96, which was leading up to the Super Bowl season. And after a lot of meeting with doctors and talking to my head coach, Mike Holmgren, Ron Wolff, our GM, my wife. Everyone agreed I needed help, and this is when I was at 16 Vicodin ES. And they said, "Brett, you have to go to treatment." And I was like, "No way. I'm not I going to rehab." Ultimately, they won and I didn't ....

Christina Brown Fisher:

So, you had to be sold on rehab even after two seizures?

Brett Favre:

And then some. I was defiant, to say the least.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay.

Brett Favre:

But it was funny, I went home to Mississippi. We went home after, you know, after talking with the neurologists and stuff and went home and I was still taking pain pills, and this was March and then April. Training camp was scheduled to start mid-July. Something like that, and I was I got to a point where it was harder to get the pills and I had like 12 pills like this one. I'll never forget this one, and I'm going to say it's probably May or June. I didn't have 16 and I remember laying by the toilet, just me and me and the toilet and 12 pills, and I bet I sat there for three hours contemplating putting them in the toilet, flushing them down because I knew 12 would not help. And it wasn't going, it wasn't going to give me that euphoric feeling, and we had already had talks about going to rehab and all that stuff, and I was like, I'm gonna flush these down the toilet and I'm going to end it right now I'm stopping. So, three hours of contemplating eventually I flushed them down the toilet, and as they were going down the toilet, I almost went in after 'em. Now what I didn't say, and I've said this in many interviews, is prior to this, like, like the last year leading up to this 12-pill moment. Part of this would be during the season, part of would have been the previous offseason, so a year. I would be somewhere and at 9:00 keep in mind, I will take the pills regardless of where I was, unless we were playing a game at that time. You got to a point where it was hard to swallow the pills, like I had this gag effect. So, I was drinking and partying at the time, you know, at that same time I'm taking pain pills and stuff. So, I may have been, you know, in a bar, restaurant, drinking, and I would, it would be time to take the pills and I would go, like, in the bathroom. And I would take the pills and I would get them down, and oftentimes I would throw them back up. Now it's horrible and I talk about this. And, you know, I think what was I thinking, and I would, they would, the, the pills would be on the floor. You know, kind of soggy, and I would pick each one out of the vomit…

Christina Brown Fisher:

You would pick up the pills that you just vomited and try to take them again?

Brett Favre:

I was not going to waste 'em.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Okay.

Brett Favre:

And I would make sure that off the floor off or whatever. Yeah. I mean. You would think at that point you go, “I got I got a bad problem,” but it was just part of the deal.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Well, that's part of the addiction.

Brett Favre:

Exactly, and, you know, I didn't tell anybody that because, God forbid if I told someone that they would think, "You, you got a serious problem," which I'd did, but I didn't I did. Even, even though, even though I was picking pills out of the vomit. So fast forward to the 12-pill moment I flush 'em down the toilet. I went about a week. Yeah, I'm, home, you know, I'm home. I mean, me, and Deanna, and my daughter we're home. You know, I'm away from the football atmosphere and stuff like that. So, a lot of times I was my own, well come 9:00 at night for about a week, I would be in the worst sweat, cold, shivering, you know, having...

Christina Brown Fisher:

You’re going through the withdrawals?

Brett Favre:

So when I did, I actually was two months, probably removed from pain pills, and no one, no one believed me, no one knew before I went to rehab, and I had a public press conference in Green Bay, where I admitted that I had a pain killer addiction and that I was going to receive treatment and be in treatment for as long as it took, which happened to be in Topeka, Kansas, where the League had a contract with Menninger Clinic, and I was there 73-days, and the reason I was there 73-days I remember when the first week I was there, you meet with all these doctors and they kind of give the lay of the land where you are, and I said, “I don't take that pain pills anymore.”

Christina Brown Fisher:

So, were denying that you had a problem when you got to rehab?

Brett Favre:

Yes and no, I think I admitted I had a problem but not anymore because I'd quit taking pain pills and they said the underlying problem is still there. You don't know why you had this problem; you know. First of all, you should have never stopped taking the pain pills the way you did because you can die because of withdrawals. Especially someone who was taking 16 Vicodin ES at one time and I'm like, "yeah, whatever." You know, I fought them tooth and nail. They're like, "you're going to meetings, 12-step meetings." We'd go to town and to places in town, and we sit around the circle, and we tell our problems. And I said, "I'm not doing it." And they go, "well, you won't get out of this treatment center unless you do what we say, because the League cannot, unless we sign off on it, you're not leaving." So, what should have been a 28-day stay, ended up being 73. I mean I punched the wall. I argued. I yelled, "I don't have a problem," and, and I think when I left in 73-days, I'd sort of, the last week had kind of like, played the game. "You're right, you know, you're right. I was wrong."

Christina Brown Fisher:

You said what you needed to say.

Brett Favre:

You know, I went through all the hoops and all that stuff and they released me. I went back, I was in tremendous shape. But what a lot of people didn't know and probably still don't know is, they, they, there was a drug that was out, and I say drug, it's called Ultram. I don't know if you're familiar with it. It's a, it's a non-addictive painkiller. So, they said this is what you can take from here on. Well, lo and behold, if you take 20 of them, you can actually a little bit of a euphoric effect. And I took Ultram and was going back to where I was before then, and fortunately nipped it in the bud. Oh, and the remainder of this was like right at training camp the early part of season, and I did not want to fall back in that trap and from that point on, after the Ultram incident, I've never taken a painkiller since.

Christina Brown Fisher:

What about now, coming off the heels of your hip and back surgery? Were there moments where, well, you thought about it? You considered it?

Brett Favre:

Oh, well, I thought about it, you know, and I'm to a point where and I think this is an addictive part of it that never goes away. There's a part of me that thinks I can take pain pills. For not a year after I've quit pain pills altogether, after we won the Super Bowl, I had my wisdom teeth cut out, which is kind of late, you know, at 27, I had them cut out here in Hattiesburg. And the doctor, I'll never forget, he said, “what pain pills do you want me to prescribe for you?” And I think he he had no clue what was going on. And I said, “none.” He goes, "what do you mean, none?" I said, "I can't take pain pills." He goes, "oh, you're gonna need pain pills." I just, you know, like he was chipping out the teeth and, you know, I mean, he said "you're going to be in major pain." I go, "I can't take pain pills. I got a problem," and I didn't take pain pills. And it hurt and I had to endure, but I didn't take it unto this, till this day I have yet to take a painkiller. Now, you know, when I came out of the hip surgery, I walked out that day. But it was a nerve block and like a day-and-a-half later when it, when it wore off. It wasn't, fortunately, it wasn't terrible. I mean it was sore, but, you know, I was fine. I'm hoping it's not super painful that I'm very tempted to take something. But up to this point, getting back to what, what I was saying is like, I feel like I could get in and maybe I could, maybe I could take two pain pills, have a little euphoric feeling because I know that's going to happen. Kills the pain and I go, that's it. You know, I'm not taking anymore. Maybe I can do that, but I don't want to. I don't want to try.

Christina Brown Fisher:

Right, you don't want to test it, I guess?

Brett Favre:

You know, when I was in there for painpill, like, you know, those 73-days, there was a couple of moments where the acting clinician brought up drinking, and I, I stayed away from it as much as possible. I did not want to bring it up. I wanted to hold on to the drinking part of it. If I can't do pain pills, at least I can drink, and they brought it up. “How much do you drink?” And, I said, "I, very rarely you know I may have a, you know, two or three beers every so often on the golf course or something," and they're like, "Okay," and part of that was true. I didn't drink all the time, but when I drank, you know, and you probably heard this too. It's so absurd, you know, I thought I had it all figured out because I didn't drink all the time. And an alcoholic drinks every day. No. You're an alcoholic because when you drink, you don't drink one, you drink to get drunk. And that's how I was. I mean, I drank for the effect. Why would I drink one beer.