A large part of my personal motivation for creating this podcast — is the privilege of speaking with those who I consider to be elders, those who have lived their lives to the absolute fullest and have stories and insights to share with younger generations about what it means to truly live well.

And this conversation with Kevin Kelly turned out to be exactly that. You'll probably want to have a pen and paper handy to take notes, and it was so rich with practical wisdom — in part because that was the subject of Kevin's new book — called 'Excellent Advice for Living'

Some of the pieces that resonated most with me were:

- How his curiosity and obsession with tinkering & making things paved the way for his later career

- Why giving your time away is by far that's the most valuable thing that you can offer

- The immense value in designing family rituals and rites of passage

- Why he believes that AI will eventually want to have an identity and a name and will act as a forcing function to propel us forward — like children do, to be better than we would have been

- Finally, why we should attend as many funerals as possible — and endeavor to become fully ourselves

⏳ Timestamps

[00:05:07] Thoreau and the Whole Earth catalog were influential in shaping the interviewee's passion for inventing their own life and stripping down to the minimum to achieve contentment. Thoreau was a mentor and hero while Stuart Brand was a greater influence.

[00:09:15] Deep listening means trying to hear what's unsaid, not just focusing on responding. It involves being affected by what's being said, not just hearing it like a recorder. Many people don't truly listen and miss out on understanding.

[00:13:08] The worthiest projects take five years to complete, but prototyping is important too, and only one five-year project should be focused on at a time. Anything worthwhile should be accounted for as a five-year project.

[00:17:14] Textual content is created as reminders of timeless wisdom from past philosophers and religions. Advice includes putting things back where they were found and deciding not to be outraged for a day. These reminders are short and condensed, meant to be easily remembered and applied.

[00:20:50] Invest in a donor appointed fund that grows and can be given to high leverage charities, which teach people to fish rather than just giving a fish. Volunteering and donating time is the most precious thing to give.

[00:25:19] Parents celebrate their kids' coming-of-age at 21 with a small ceremony where they cut a symbolic cord, give them their last check, and allow them to drink legally. The event sometimes includes wagers or promises, and kids add their own innovative participation. One child ate paper with advice written on it.

[00:30:30] Create family rituals to provide stability, consistency, and a sense of anticipation for children, which will become part of the family identity and provide comfort in adulthood.

[00:34:21] The author believes that technology has tendencies that are independent of humans, and that consciousness, sentience, and identity may be inevitable for technology. He thinks that technology may want a name.

[00:40:36] The goal is to fully become yourself with the help of others, it's a long process involving constant self-challenge and it's the key to accomplishments. Attend funerals to hear about character over achievements. The question to ask is "who do I want to become?".

[00:47:02] AI development will force us to question what we want the AI to be like, as they will carry biases and issues of average humans. It will lead to a discussion of how we can make ourselves better as well.

Official Links

📚 Order Kevin's book 'Excellent Advice for Living'

👋 Follow Kevin on Twitter @kevin2kelly

🖥️ See Kevin's homepage and extensive bio — kk.org

Connect + Explore More from Jonny

🐦 Follow on Twitter/X @jonnym1ller

🫁 Learn more about Nervous System Mastery

🪷 Order our deck of Calm Cards (these make great gifts)

📱 Check out Stateshift — our brand new iOS + Android app

📝 Take the Nervous System Quotient (NSQ) Self-Assessment (totally free)

💌 Sign up to The Inner Frontier Newsletter

Episode Sponsors

🌬️ Othership Breathwork App — I've written at length about why breathwork is like the operating manual for your nervous system, and I have been highly impressed by the app that the Othership team has created. You can choose between guided daily practices that will up or downshift your state, as well as breathwork journeys that focus on embodiment for cultivating intimacy, athletic performance, or preparing for sleep. Exclusive to The Inner Frontier listeners, you can get a three-month subscription at zero cost to take it for a spin. Claim the three months

🩸 Inside Tracker — One of the things I've changed my mind on in the past year is the value of getting blood panels taken prophylactically — ideally every six months, according to Dr Peter Attia — not waiting until you have a health issue. They recently added hormone testing to their plan, which already includes important markers like ApoB, vitamin D, magnesium, cortisol, and a bunch more (47 biomarkers in fact!) I received some super actionable supplement changes and dietary shifts based on my results and I'm noticing the shifts already. Save 20% here

Further Ways to Support the Podcast:

🎙️ I use Riverside to record all of my podcast conversations, it's so much better than zoom for podcasting

🎧 I also use Transistor to host this podcast, it's fricking awesome, and I would highly recommend.

😎 RaOptics make the world's best Blue Blockers – I wear these anytime I'm out of the house after dark, and it makes a huge difference!

🤖 I use AI wizardry from Castmagic to help with each episode show-notes + timestamps

📹 Want to create a Hollywood-quality home studio? Get in touch with Kevin Shen here & save $500 with code JONNYSENT500OFF

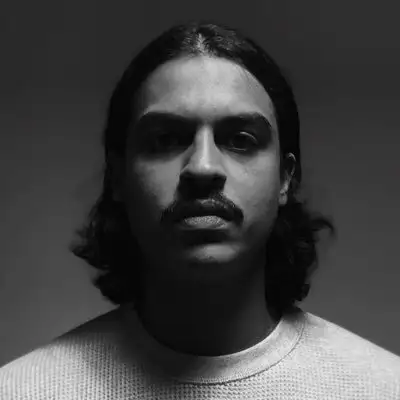

Creators and Guests

What is The Inner Frontier with Jonny Miller?

Deep dive conversations that celebrate self-experimentation, share evidence-backed tools for learning about your nervous system, and explore how to create more flourishing in your life.

Jonny Miller [00:00:00]:

Hello. Welcome to the Curious Humans podcast. Kevin, it is a real pleasure to have you here. How are you feeling right now? In three words.

Kevin Kelly [00:00:12]:

Very excited today.

Jonny Miller [00:00:17]:

Nice.

Kevin Kelly [00:00:18]:

Very excited because my book just launched just yesterday. It was us the on sale date. It's been many months in preparation, and it's the day when the people receive the books for the first time, and I get to hear what people thought. So today they're kind of coming in all the messages, and it's just really been fabulous to be able to share with that.

Jonny Miller [00:00:49]:

Beautiful. Yeah. A bunch of my friends on Twitter have actually been posting screenshots of the book as well. And my friend Kyle has even published a book review already in the short period of time that it's live. Yeah. That must be a great feeling, to kind of have it out in the world.

Kevin Kelly [00:01:04]:

Yes, exactly. It is really great. It doesn't last. There's still a lot of work to do to help promote it, and that's sort of what book publishing these days is not very difficult to make something, but it's very difficult to kind of distribute and promote it.

Jonny Miller [00:01:22]:

Well, to kind of dive in. I really consider you to be one of the most eclectic and intellectually adventurous humans alive today. And if you think back, this is the question that I begin most conversations with. Do you think that you were exceptionally curious as a child? And if so, could you maybe tell me a story about something you were curious about?

Kevin Kelly [00:01:49]:

I don't I would not have described me as, say, the most curious child. I think my superpower, if I had one as a kid, was I was a maker. I made stuff. And maybe that's one version of being curious. And so I was curious to the extent that I wanted to make things. And so from a young age, I was making model railways, scrounging for things in the neighborhood, in the factory backyards and stuff, scrounging stuff to be able to make things because I had no money and I didn't have an older brother. And it was just I was kind of on my own trying to discover how to do stuff. Going to the library. And I made later on, I found a book about how to make a nature museum, and I decided I wanted to make a nature museum in my basement. And I was going around learning about things, how to collect them, prepare them, mount them, make exhibits and stuff. And later on, I got into science and chemistry, and I built, when I was a kid, a chemistry lab, and that was what I asked for. My birthdays was chemical glassware.

Jonny Miller [00:03:06]:

I bet your parents love that.

Kevin Kelly [00:03:11]:

I was one of the very few kids in America to have a full functioning chemistry laboratory, and I never made a bomb. Once they have chemistry, they make one. Explosives, I didn't have any interest in that for some reason, so I was too cautious. So anyway, that was my version of curiosity, was making things that is still part of me. I'm in a two story library, and I just finished making Going Back to Childhood and made a model railway around the perimeter of the ceiling and made some bridges out of electric sets and stuff. I built the house. I just like to make things, make books, make websites, make companies. That's my version of curiosity.

Jonny Miller [00:04:11]:

I love that. Well, you've just published this gorgeously, refined book that you just mentioned. It's like a collection of proverbs called Excellent Advice for Living. And in some ways, I felt almost like a kid in a candy store kind of reading through, and there's so many threads that are alive. So I feel like this conversation might be almost like a chef's tasting menu for ideas. Okay, so I'll follow some of this.

Kevin Kelly [00:04:37]:

What's the first course?

Jonny Miller [00:04:38]:

Yeah, so first course starters. The appetizer self permission was the theme. And as anyone kind of familiar with your story, I feel like you've lived this outrageously full life of making so many things. And I think a question that came to mind for me was where do you think this maybe, like, radical sense of permission came from to follow these impulses?

Kevin Kelly [00:05:07]:

I'm not I grew up in a pretty parochial, isolated, culturally isolated, suburban New Jersey household with a lot of siblings in the I'm not aware of any inciting influences on my eagerness to kind of explore and take a different path. Except I did read Thoreau in high school, and that did touch me in a profound way. He became my hero, and I drew pictures of him to put up my wall. And he was, in some ways, my mentor. And there was something about the beauty of first his prose, of course, the way he writes, but also what he was doing with his life that said, okay, I think that's sort of what I'm about. And then later on, he discovered the Whole Earth catalog shortly after that, and that was like, okay, now I know what I'm about. And that's my dream was to work for the Whole Earth catalog someday, little knowing that I was actually going to run it at some point. So that idea of inventioning your own life, of stripping things down to the essence to discover the first principles, entrepreneurs talk about going back to first principles to try and invent things. Well, Thoreau is kind of going to first principles of life, of saying, what's the minimum that you need to be content? And then can we build up from there? And just the idea of that kind of volunteer simplicity as a means to have the full enriched life, that paradox. And so Thoreau might have been maybe that kind of inciting mentor that set me on a certain direction in the Whole Earth catalog? Absolutely. For sure. That would be Stuart Brand he was the second and maybe even the greater influence on me. And I discovered that right at the graduation of high school.

Jonny Miller [00:07:38]:

I love that. There's a book that I remember reading by stephen cope called the great work of your life, and he uses thoreau as a case study. What I found particularly interesting was that he originally wanted to be a journalist in New York City and he kind of didn't make it. And he made this decision where he felt like a failure, like moving to Woolden Pond. But it was really through following that kind of quiet voice and finding that solitude that he was able to produce the great works that we know him for. He's really inspiring character.

Kevin Kelly [00:08:06]:

Exactly. Yeah. It's another beautiful example of not really depending on too much where you start, because your life's going to take right turns and detours and switchbacks, and you're going to end and go in a direction that you didn't begin. And that's normal that's young people you should expect that it doesn't matter whether you're washing dishes or an intern at advertising. You can see it doesn't matter where you begin.

Jonny Miller [00:08:42]:

Beautiful. Well, the next course, I guess, the theme is listening. And one of my favorite highlights was from your book was Listening well is a superpower while listening to someone you love, keep asking them, is there more? Until there is no more. And I really love this. And what came up for me is I sense that there are almost good and bad ways to listen. So is there anything that you'd say to that? And maybe, what is learning to listen well given you?

Kevin Kelly [00:09:15]:

Yeah, I think later on I might have a little piece of advice about you're listening not to design a reply. You're listening to try and hear what is unsaid. So there's a tendency in listening at the superficial level where you're kind of like, well, this is a conversation. I'm going to be working on what I'm going to say back. Whereas one form of deep listening is you're really listening to what they're saying and you're kind of trying to hear what's not being said as a way to kind of even go deeper other ways, other things about how to listen well. So at one level, I'm interviewed by a lot of people, and particularly in China, because most of my fans are in China, there's a tendency to have a conversation where they ask a question, I answer the question, they ask the next question. So they're not listening. They're not responding to what was said in between. They just have another they've got the next thing. I think listening is in a way that you are allowing yourself to be affected by what is being said. Right. So it's not just like you're not recording it. It's not like you're a tape recorder where you're just hearing it. Listening is where you're being affected by what is being said in some capacity, whether it's an emotional affection or whether it works at the logical level. But that's the difference between just hearing something and listening to it.

Jonny Miller [00:11:23]:

Yeah, I feel like there's almost this receptivity that's present in a sense of maybe even like impartiality and vulnerability as well in there.

Kevin Kelly [00:11:37]:

Yeah. I mean, a lot of marriage counselors will tell you that often what people need when they're upset or not feeling well or depressed or all kinds of things is someone who's listening without even saying much. I mean, literally just receiving it. And that's often all that is needed is no more or no less than actually just listening. You don't have to offer a solution. You don't have to offer a comment, you just have to receive it. So I think you're right in that way.

Jonny Miller [00:12:17]:

Yeah, I love that. Okay, well, another theme that I'd love to touch on is kind of like zooming the lens out. And I felt, at least in my interpretation, patience was another theme in your book. And I've had a few conversations with a friend and mentor of mine, young Chip Chase, who consistently reminds me to zoom out and think in the longer term. And I know that you've tended to only, or at least I've heard this, you've tended to only take on projects in kind of five year increments. And for someone like myself, I tend to create things and really just think on a much shorter time horizon. And so I'm interested in hearing how have you learned to adopt this broader temporal lens.

Kevin Kelly [00:13:08]:

Just to clarify things and make it clear. I think that the projects that are kind of worth doing and that become significant in my experience and other people's experience will take five years from the moment that they're first thought of to you to the moment you stop thinking about them. And it isn't that I don't work on something unless it's a five year thing, because I can't plan that way. What I mean, I'll do lots of little things because I believe in prototyping rather than making grand plans. Prototyping. And iterating your way to things. I will be working on things, but many things and trying them. And iterating small things, small steps, but not intending to let more than one five year thing or get big enough to be a five year project at a time. So it's a way of sort of focusing in a certain sense on that and kind of saying, well, okay, if I'm going to do a book, even including this little tiny book, that I have to kind of resign myself to the fact that this is going to occupy five years somehow or other. It doesn't matter how small it is, whatever it is in the end, from the first glimmer of writing these things down or whatever, it's going to be a five year project, and you can't escape it. So it's more of a kind of saying not a way of making things bigger, but it's saying anything worthy, you should account for as if it was a five year project.

Jonny Miller [00:14:56]:

Got it.

Kevin Kelly [00:14:57]:

So I do lots of little things in between, but anything big, you have to kind of in your mind say, well, I get to do one of those during this time. You can't do two of them at the same time because they're one five year project at a time. And so what's it going to be? Is it going to be this or is it going to be that? Because they're both are going to consume five years of my attention.

Jonny Miller [00:15:26]:

Got it. So it's like a forcing function for your attention in some ways, yes.

Kevin Kelly [00:15:32]:

Right.

Jonny Miller [00:15:33]:

Got it.

Kevin Kelly [00:15:34]:

It's not so much how you get going or whatever. It's saying that a project is sort of a commitment and you have to be willing to commit a certain amount of your attention to it, or that it's going to because it's going to demand it. Whether you want to give it or not. It's going to suck that much out of you. That's the cost of it. There's an attention cost. That attention cost is like five years. So if you really want to go down this thing of doing a startup, or if you want to go and do attention jobs, or if you want to do something else, you say, oh, that's going to suck. The total suckage of this is going to be five years.

Jonny Miller [00:16:27]:

Got it. Okay, well, I was reflecting on the nature of advice itself as I was reading your book. And my experience is that advice for the most part is quite useless in some ways. But what I felt from reading was it was like a distilled collection of rememberings. That was how it felt to me. And I mapped some of the proverbs to my own experience and it felt like there were like concentrated shots of a sense that, yeah, I need to actually embody this. I need to kind of remember this on a regular basis. So do you think, could you speak to this and maybe what is the journey that you've been on to live some of these principles or some of these things that you've written down?

Kevin Kelly [00:17:14]:

Yeah, I think you're really close to the mark. I think of these as reminders. They're reminders. Basically everything important has already been said, but nobody was listening, so we have to say them again. These are reminders and the best ones are working at the level of the timeless wisdom of the past from the Stoics and Confucius and the Bible and Zoaster and the Zen guys. So I'm channeling things as a reminder and what I'm trying to do is put them in my own words in a way that are more memorable for us today. And that encapsulation, I think, is important. That's why I began writing these down was for myself, to help me hold them handle them and bring them up to remind myself of them, to make the habit. And so my bit of advice about if something gets if you can't find something in your house, you know it's there and you find it when you're done using it and you begin to put it back, the reminder is put it back where you found it. Put it back where you first look for it. So I tell myself that little story, put it back where you first look for it. It's a reminder. And so I want these things about if I'm starting to get outraged, decide today not to be outraged today. Right. So it's like you make this decision, so not to be outraged, that's your thing. Maybe tomorrow, but today I'm not going to be outraged. Okay, all right. That's just the handle. They're a little handle encapsulation. They also, by the way, happen to travel very well on the Internet, which is another benefit. But the main reason I did it was for myself to give a little way to hold these books, vast bits of wisdom encapsulated and condensed and distilled into this little thing that I could remind myself with.

Jonny Miller [00:19:33]:

I love that. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And it's harder to remember things longer than a few tweets worth. I suppose that's just a function of human attention. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Well, another reminder that I loved was I've got it written down here. When you give away 10% of your income, you lose 10% of your purchasing power, which is minor compared to the 110% increase in happiness you will gain. So I love this one. And what are some of the most joyful or joy inducing ways that you've given away money? What's an example of that?

Kevin Kelly [00:20:14]:

There's a couple of things. I have given some money anonymously to people that I knew needed money for personal reasons they didn't know that I knew. But any case, that was a tremendous joy because what happens when you give that kind of that way anonymously is the people receiving it begin to suspect everybody as being the first one.

Jonny Miller [00:20:48]:

Oh, I love that.

Kevin Kelly [00:20:50]:

Right. It's really kind of cool. It's like someone just changed our lives. We don't know who. Was it you? And they can't say. So anyway, that's a great way to do it. This is kind of beyond the scope of it, but I suggest everybody that they set up a Fidelity, kind of what we call it, charitable trust fund, donor appointed fund. So what it is, is you can gift it and anything into that fund, it's like an index fund, stock fund has to be given away to a verifiable charity and you can take the tax deduction when you give it. But the thing about it is that it's a fund that's growing. It's growing like any other index. So you give some money and if you don't give all of it away that year it begins to grow and you have more money to give away. So we tend to use that to fund what I would call high leverage type of charities. And those are the kind like Micro loans. Micro finances the HYPHER project, which gives breeding pairs of animals to people, but they then have to give one pair of breeding animals themselves once they get going. So it passes on, keeps going. So those to me give me great joy because they are enabling kind of charity of not just giving a fish but teaching a person how to fish, that kind of stuff. And so that I find really great in terms of giving and it's of course true that the most valuable thing that we have is our time more than money. And if you give your time away by far that's the most valuable thing that you can give and why? Again, one thing I learned and I wish I'd known earlier was that that was the highest leverage was giving other people to give you their time. You give them a little bit of money, they give you your time. Well, what a bargain. Because that's the only scarce resource in the universe and so giving away your time and donating volunteering is by far the most precious thing that you can give. Not necessarily the most effective but at least the most precious.

Jonny Miller [00:23:24]:

I love that and I really love the first example of giving anonymously and I hadn't thought about it having that impact of potentially changing someone's perspective on the world. It's almost like giving a more generous lens of generous assumptions potentially to others.

Kevin Kelly [00:23:41]:

Yeah, it kind of only works in a kind of personal level. There's lots of anonymous gifts giving it to high level but if you turn to personal level and you hear about somebody whose life really that you know, that could really make a difference and you give it anonymously it's kind of tricky. You can do it. As I said, it can change their perspective because they enter pronoia and you've heard of pronoia. Pronoun is the opposite of paranoia. Paranoia is where you convince that the universe is conspiring behind to take you down. Whereas pronoya is this idea that the universe is conspiring to help you in your face. If someone's anonymously among your acquaintances given you something it's like you are going to be suspicious and suspect each one of them being a generous person.

Jonny Miller [00:24:38]:

That's so great. Yeah, I love that. So I wanted to talk about this is maybe lunch or kind of like third course is on right to passage and the words that you wrote here are we lack rights of passage. Create a memorable family ceremony when your child reaches legal adulthood between 18 and 21. And this is something that I've discussed a lot on this podcast. I've taken part in Vision Quests myself and spent ten days in a dark room. But I'd love to hear what are some ideas for rite to passage or family ceremonies that you could share that might be accessible to listeners.

Kevin Kelly [00:25:19]:

So we had a rite of passage for our three kids and we chose the age of 21 as that. And so we had a little ceremony that they could invite a few close friends if they wanted to or we had family members, but it's very, very small. And the kinds of things that they did was the following one thing was that we did the same for all three kids and then they each had some participation in some innovation and some things that they added themselves. But the one that we did, the parts that we did that were the same was we began this ceremony by tying a red ribbon between my wife and I and our child. That was the we came into that and they would take a big scissors and we were cut the umbilical cord. We were cut the cord. And we'd have a little kind of ritual saying and announcement that we were cutting the cord. And then we would literally say, this is your last check. And we would give them the last check. Our support for you was ending and you were going to take over your own. You're going to be self sufficient in that sense. You're going to be kind of like an adult. And then we also would have their first legal drink, a toast with their first legal drink, and they would share the wine. And then there was some of the kids had a bet or a wager or a promise from us. And there was another check, I guess that may be before the last check, but we had promised them $1,000 if they didn't smoke or drink before they were 21. And that was based on something that I did with my parents when I was growing up. So they, they heard about that and they wanted to do that when they were kids, when they didn't know any better. That was something that we did. And then my son, he decided that what he wanted to do was he got edible paper and edible ink and had everybody write some bits of advice on the piece of paper and then ate it.

Jonny Miller [00:28:03]:

You should print him an edible copy of your latest book. Exactly.

Kevin Kelly [00:28:07]:

Maybe that's where the idea came from.

Jonny Miller [00:28:10]:

Wow.

Kevin Kelly [00:28:10]:

So that was idea of the communion of advice. And then he later we lived near the beach. He went down to the beach. He says, I want to be baptized. I want to walk into the ocean. I want to dive into the ocean a boy and want to walk out a man. It's like, wow, okay, we're going to do that. One of my daughters wanted to be baptized in the hot tub, in our hot tub. Okay. So she had one of her cousins who was a minister, youth pastor. She came and he baptized her in her hot tub. And my other daughter, she baked a bread herself and then she fed each person it was like, again, like another communion. She fed each person this bread with some kind of significance and she had another ritual, which I'm forgetting right now, that she had invented again to mark the passage and all that. There was a number of things, some of it, as I said, that we initiated, some of that they did and it was a very memorable time. It was definitely this idea that they were transitioning and we marked it and it was known and it was part of their identity. Now.

Jonny Miller [00:29:43]:

That's beautiful. Yeah. Did your son do anything in particular when he went into the ocean? Or was it just a kind of metaphorical breath?

Kevin Kelly [00:29:53]:

We are the ocean freezing. It's a shock when you dive in. No, that would have been nice to do, but no, it was go in, come out alive.

Jonny Miller [00:30:10]:

That qualifies. Yeah. Rituals, it seems to be another theme of the book in some ways. And I I know you've written about the Sabbath as well. Yeah. How how is that or any other rituals kind of enhanced your life and and maybe how are they how is it just different from a habit?

Kevin Kelly [00:30:30]:

Well, yeah, as I said, love is the book was written kind of with the idea of wisdom I wish I'd known earlier. And one of the pieces that I wished I'd known earlier I generally regret not understanding that was this idea in our family of having as many rituals as possible for family rituals and making a ritual is basically anything that you do three times in a row is sort of a ritual. They don't have to be significant. They don't have a big profound meaning. They can be just like every Friday night you have home baked pizza in the movies or every Sunday morning you bake pancakes or every birthday begins with this song, or every season on the Equinox you go outside and you holler at the moon, whatever it is, and you do it on a repeating basis. The key thing is there should be expectation. You want the kids in the family to be anticipating anticipating this. Oh, I can't wait. This is what happens. And we do this once a year we do this and every 4 July we do this. And so there is a sense of anticipation. And the thing that it does is that repetition is incredibly grounding. It's anchoring to kids because the thing that they prize most is consistency and reliability and stability. That's why family dynamics are so upsetting. If they can't count on it having something that they can count on and these are kind of visible markers of that. You can count on us. We are here, we're going to be there every time. Don't worry about this. You are anchored. And that's what they do unconsciously. The fun little part of them is it's fun? That's not where the meaning is. But as they get older, these little things that you always do become part of the story, the legend of the family, part of the history of the family. And I think having a family identity is also incredibly important for kids as they grow up, because, again, it's more anchoring as they are developing their own identity, to have the family identity be there and kind of a given really enables them to kind of step out and become more individually identifiable. And so these things become more important. And nowadays, as young adults, they look back on them and they talk about the things we always did, even though you might do them a couple of times a year, but they were institutionalized and ritualized, and they hang on to them. Now, again, they're kind of landmarks or ways in which they're safe harbors. They're there. And when I think back of them, they're comforted by them.

Jonny Miller [00:33:37]:

That's beautiful. I wasn't expecting you to say that, but I can really see how there's a sense of embodied safety, particularly on the threshold of stepping out into the world and where there's so much uncertainty having those anchors. Yeah. That's beautiful. Yeah. Thank you.

Kevin Kelly [00:33:56]:

You're welcome.

Jonny Miller [00:33:59]:

So a question from I asked a few friends what curiosities they might have for you. And my friend Buster Benson was curious to ask, what have you realized that technology wants based on the last three to five years that you might not have guessed when your book came out and are at once changing? I thought it was a great question.

Kevin Kelly [00:34:21]:

That is a great question. That's just a good question. I need to think about it for a second here. I'm going to restate it just to give myself some time. So I wrote a book called What Technology Wants. That's what it's referring to. And the idea there is that we want to listen to technology to see which way it leans and what its tendencies are, to understand it. And those systematic characters are kind of independent of what humans themselves just by the nature of the physics and geometry of these technologies as a system. And I had a bunch of different suggestions about the trends and biases and tendencies of technology in the book. And the question is, since the last since the book's been released, 1015 years, what's new? What are some of the new things that I understand about what technology wants that were not in the book? I think so one of the things I did say that technology wants is mindfulness evolution has produced brains and nervous systems and all kinds of ganglia and thinking multiple times independently. So it kind of wants to produce that. And producing AI right now is totally in line with that. So that's why I would say AI was inevitable. It wants AI. But I think I'm thinking out loud here, but. But it might be that one of the things that AI wants is an identity is, I think, the idea of we were just talking about young children growing up and taking on identity. And so I think we don't understand what intelligence is. We really have no idea. And these other higher levels of consciousness sentience, we don't know what they are, but it might be that one of those ingredients. And by the way, I think those are kind of all inevitable, and they are things that we're moving towards and that technology does want consciousness and sentience, but there might be another one that's maybe part of that mix, which is identity. Having an identity, having it's more than just having a self. It's having a self that other people know. Or I haven't really thought about exactly what I mean by identity in technology, but it might be something along the lines of I wouldn't say having a brand, but having a way of describing yourself or labeling yourself, or calling yourself. It's like having a name. Okay, so maybe it's like maybe what technology wants is to have a name at some point, to have a name. And that wouldn't surprise me. I have to think more about whether I really faint that that's where it's going to see what the evidence for that is. But that's the best I can do right now, thinking off the top of my head. So I would say it may be that technology wants a name.

Jonny Miller [00:38:34]:

That's great. I know you've talked about AIS being more kind of relevant than just AI. So presumably there'd be many names, many identities to correspond with many different types of intelligence.

Kevin Kelly [00:38:50]:

Right, exactly. I'm sorry. It should make it clear because I always think in plurals, but yeah, each technology wants a name or something like that. Technologies want names. Yeah. That's a good clarification, because I think it's very important that we think in terms of plurals. And that's one of the distinctions. And the reasons I disagree with those who think that there's an existential threat with AI is they always talk about monolithic AI that takes over. It's one huge super organism, superhuman AI. And I think there's just going to be hundreds and thousands of species of AIS all competing in some sense, like an ecosystem competing in cooperation. At the same time, I think that makes it less likely of being taken over by a single AI. It's like, say, well, there's a single giant Borg organism that's going to take over the planet. And I think that's possible, but unlikely.

Jonny Miller [00:40:00]:

Yeah. This actually nicely dovetails into maybe one of the final themes to explore here, which is a sense of full expression and becoming fully yourself. I believe you wrote, don't aim to be the best, but aim to be the only. And so I guess my question is, do you feel like you're being fully Kevin? And what have you observed about the invisible barriers to being fully ourselves. What gets in the way of that?

Kevin Kelly [00:40:36]:

Yeah, that's definitely a main theme of the book, and I have many other variations of that. From you want to aim so that on the day before you die, that you can say that you have fully become yourself. Right? So that's the trend that you want to aim for. You'll not ever arrive there, but you'll be headed in that asymptotic direction of always approaching it. And it's a very high bar. It's very hard to do that. And several things we know about it, one is that it will take most of us, including me, most of our lives to kind of get anywhere on that journey. And secondly, it's weirdly and paradoxically, the only way to fully become yourself is with the help of everybody else. You can't do it alone, so you can't fully become yourself. You need family, friends, colleagues, mentors, customers, clients to all help see who you are and who you are becoming and to help you on your way to become the best you. So it's the process that, one, takes all your life. Two, involves everybody around you. That's why we're all here, to help each other become ourselves. And three, you're not going to end up it doesn't matter where you start again because it's a very long and meandering journey with many turns and setbacks and detours. And then four, I think it requires constantly asking yourself, constantly challenging yourself, it requires all these other habits that we're talking about. It's work, it's deliberate. What's the word I want? That is your occupation. In the end, part of what we see with artists and part of what we see with innovators and entrepreneurs and what we see with great scientists who have accomplished something, all those achievements are really emanating from their person, from who they are. And I mentioned another piece of advice, which is attend as many funerals as you possibly can and listen to what they say about the departed because they very rarely talk about the departed achievements. What they mostly talk about is the departed's character, their being, who they are, who they became, how they made people feel, and that's their being the person. And so from that from your person and who you are comes off yield. It's a byproduct of who you are. It stems from it. So you kind of want to work on who you are. And that's another piece of advice. It's like the the best way to answer the question about what to do next is to ask yourself, who do I want to become? Okay? So that becoming you is your life's work. That is your job, that is your occupation. And from from that will come the achievements.

Jonny Miller [00:44:36]:

Yeah. Yeah. Beautiful. It reminds me of there's a line from the poet David White, and he says, when you're attending a funeral, when they're reading through the list of achievements, the room is still quiet and cold, and they fall away like chaff in the wind. And it's only through listening to what it was that they loved. That was his point exactly. Yeah. I've been thinking a little bit about kind of how this, how identity intersects with with AI, like like you just mentioned, and and I wonder, you know, if we, if we might spend the next 30, 40 years in this kind of identity crisis, like asking what are humans good for? And, you know, maybe one gift of of LLMs, of of AIS could be that they act as this forcing function which almost necessitate that we can only do the things which are uniquely ours to do. Absolutely.

Kevin Kelly [00:45:35]:

100%, I think we're headed for 100 year identity crisis for the human race, and it's AI, it's genetic engineering as we modify our own genes. This question of who are we? But more importantly, who do we want to be, who do we want to become? Is going to be the central, overriding constant existential question. So we're just in the first dawn of that, brought on by Chat GBT, and so many people are asking that this is going to be every conversation for the next 100 years is going to be basically revolving around that very question, because we will make things doing the things that we thought were us, including thinking. And thinking is highly overrated as a means of getting things done. A lot of young men who like to think think that the most important thing in the world is thinking. But you have to kind of, well, look who's saying this. It's people who like to think. That was the old joke about when you hear someone say that the brain is the most complex thing in the universe. Just remember who's telling you that.

Jonny Miller [00:46:58]:

Right?

Kevin Kelly [00:47:02]:

When someone's saying thinking is the most important thing, just remember who's saying that. These are middle aged guys who like to think. So I yeah, there's I think this is this is the what's the word? I want the framing for the ongoing period, this questioning about who we are, what our job here, why are we here, what are we for, what do we do? Is going to be finally, a question that is not just philosophical, it actually is going to become policy. Lawmakers will have to fiddle with it, scientists will have to engineer it. These current crop of AIS are trained on the average human work, the best of work, and the worst of humans, like Reddit Iliad and The Odyssey and Reddit. Right, okay. And so it's going there. And what they're getting, what we're getting is the average, the wisdom of the crowd, average human. And the average human is biased and racist and mean. So we're saying we're not going to accept that for our AIS. We don't want them to be like the average human. We want them to be the best. We want them to be better than us. We can program that in if we knew what that was. The question is, or the problem is we don't know. We can't describe what a better than human is. Is it woke? Is it super woke? Is it post woke? What does that even look like? So we're going to have this discussion, and we don't even know what consensus is, or whether we could have consensus or who decides. But we're going to have this thing about what do we want the better than humans AIS to be like that is going to force us if we could describe it just like having children, we are going to ourselves have to up our game as humans to rise to the level. If we can make an AI better than us, why can't we make us better than us? I think you're absolutely right. They're going to force us, propel us, like children do, to be better than we would have been.

Jonny Miller [00:49:44]:

Beautiful. And that really kind of ties in nicely with your previous thought around AI itself, like wanting identity. There's, like a kind of interesting conversation there between those two drives. Beautiful. Well, I'm aware of time. Would it be okay to ask a few more rapid fire questions?

Kevin Kelly [00:50:02]:

Please do.

Jonny Miller [00:50:03]:

And then we'll wrap up five more minutes.

Kevin Kelly [00:50:05]:

Go ahead. Let me. Great.

Jonny Miller [00:50:07]:

Okay. What is one idea or conjecture that you believe to be true but don't yet have proof for?

Kevin Kelly [00:50:15]:

I believe that the aliens are already here, the aliens from other planets.

Jonny Miller [00:50:20]:

If you found out today you only had six months left to live, what might you do?

Kevin Kelly [00:50:25]:

I've already done this once in my life, and what I did was I decided to go home and help my parents take out the garbage and do all the other stuff.

Jonny Miller [00:50:35]:

Would you do the same thing again?

Kevin Kelly [00:50:36]:

Well, they're not around anymore, so, yeah. I would think I would do very domesticated, at home things of trying to be as, trying to make the ordinary.

Jonny Miller [00:50:52]:

Holy apart from building a house from scratch. What is something you believe everyone should experience at least once in their lives?

Kevin Kelly [00:51:04]:

Burning man.

Jonny Miller [00:51:10]:

What are the elements that make travel, that make the most rewarding travel? That's a question from Yan.

Kevin Kelly [00:51:16]:

Repeat that. What are the what?

Jonny Miller [00:51:17]:

What are the elements that make the the most rewarding travel?

Kevin Kelly [00:51:23]:

The more you can leave behind, the more rewarding it will be.

Jonny Miller [00:51:28]:

What is one cherished memory from your time spent wandering Asia before cell phones existed?

Kevin Kelly [00:51:36]:

Oh, I have I have a memory of sitting on the banks of the Ganji's River in India Ivaranasi, and there was a lunar eclipse happening. And at the moment of the lunar eclipse, 100,000, maybe a million, I don't know, people all simultaneously rushed into the river. And there was a sound of kind of like the river inhaling or there was a breathing or something that was uncanny and just beautiful, and just the whole scene I just will never forget.

Jonny Miller [00:52:23]:

Wow. Okay, last two questions. What is your greatest hope for this recent book on Excellent Advice for Living?

Kevin Kelly [00:52:31]:

My hope is that it reaches three different young people and changes their lives for the best.

Jonny Miller [00:52:40]:

Last question. Given that humanity appears to be straddling the edge of multiple precipices, what does it truly mean to be a good ancestor today?

Kevin Kelly [00:52:52]:

To be a good ancestor would mean that we can or individually, I can start on something that may not be done in my lifetime whose full benefits would not occur to me at all but maybe the third generation from now in three generations where the benefits none of the benefits occur now and all the benefits happen in three generations.

Jonny Miller [00:53:29]:

Thank you so much. Well, this has been a real pleasure. I really appreciate your time.

Kevin Kelly [00:53:34]:

You asked great questions, and it was a real blast to be here and to share with you. And thank you for inviting me.

Jonny Miller [00:53:47]:

And besides buying your new book, Excellent Advice for Living, which I think would be an amazing gift, there'll be links in the show notes. It's right there, holding it up. Is there anything else you'd like to direct listeners to? Any passing comments?

Kevin Kelly [00:54:01]:

Yeah, I have a website. For six, seven years. We've put out a free weekly newsletter with recommendations. One page called Recommendo, which is free. So you can sign up there to see stuff that I recommend. No, I think that's about it. I hope people enjoy the book. It's a great gift for graduation, Father's Day's, Mother's Day, all that kind of stuff. But thank you again for this. Whatever. W. Kk.org is my initials, and then my email is not hard to find.

Jonny Miller [00:54:46]:

All the links will be in the show notes as well. Okay, well, I would like to close with this real K line. It mirrors something that the quote is, try to love the questions themselves and live them now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live your way into the answer. With that in mind, what is the question that is most alive in your consciousness right now? And what question might you leave our listeners with?

Kevin Kelly [00:55:12]:

Oh, question what should I believe? So beautiful. Thanks again. I'm late.

Jonny Miller [00:55:23]:

Thank you, Kevin. Take care. Bye.