Welcome to Season 2 of AWAKEN—a Webby Honoree podcast about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.” In this new season hosted by singer and songwriter Raveena Aurora, Buddhist teachers, writers, artists, activists, and others use a Tibetan Buddhist mandala as a guide and share how they wrestle and learn from five challenging emotions—anger, pride, attachment, envy, and ignorance.

What is a mandala? Like many Tibetan Buddhist artworks, a mandala is a visual catalyst that can lead to awakening. In our first episode, we introduce the mandala, come to understand what it represents, and experience how it may be used as a guide for exploring ourselves, each other and the world.

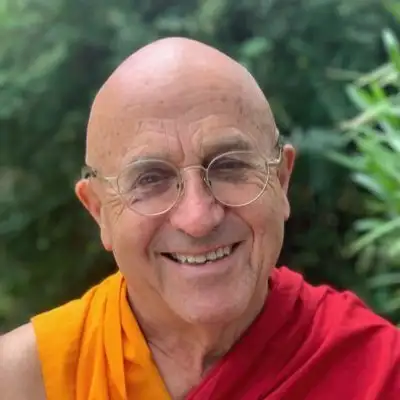

Guests featured in this episode include psychologist and neuroscientist Tracy Dennis-Tiwary, Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist Mark Epstein, Zen priest and author Ruth Ozeki, author and Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard, Buddhist teacher and scholar Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, Buddhist teacher and author Sharon Salzberg, and student Nora Wood.

To read a transcript, learn more about the Mandala Lab, donate, and more: https://rubinmuseum.org/mediacenter/entering-the-mandala-awaken-podcast

Show Notes

What is a mandala? Like many Tibetan Buddhist artworks, a mandala is a visual catalyst that can lead to awakening. In our first episode, we introduce the mandala, come to understand what it represents, and experience how it may be used as a guide for exploring ourselves, each other and the world.

Guests featured in this episode include psychologist and neuroscientist Tracy Dennis-Tiwary, Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist Mark Epstein, Zen priest and author Ruth Ozeki, author and Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard, Buddhist teacher and scholar Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, Buddhist teacher and author Sharon Salzberg, and student Nora Wood.

To read a transcript, learn more about the Mandala Lab, donate, and more: https://rubinmuseum.org/mediacenter/entering-the-mandala-awaken-podcast

Creators and Guests

What is Awaken?

AWAKEN is a Webby Honoree podcast about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.” Throughout the series we dive into the personal stories of guests who share how they’ve experienced a shift in their awareness, and as a result, their perspective on life.

Entering the Mandala - Episode 1 Transcript

Ruth Ozeki:

When I hear the word mandala…

/

/

Madame Gandhi:

I see precision. I see delicacy. I see history.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

The first thing that comes up is a visual image of the Tibetan tangkas,

Madame Gandhi

I see peace. I see art. I see a reflection of sort of like the

perfection of nature…

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

These beautiful, richly painted maps of the mind, maps of the cosmos,

maps of the spiritual journey.

/

/

Tracy Dennis-Tiwary:

If you look at the veins of a leaf super close, or the DNA of a

snowflake super close, this kind of thing of where all the sacred

geometry exists around us.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

The mandala is so intricate, and it contains so much. It contains an

entire cosmos, an entire universe, an entire mind. That’s what makes it,

I think, such a compelling image to look at.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Welcome to Season 2 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Art

that uses art to explore the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it

means to “wake up.” I’m singer and songwriter Raveena Aurora and I have

been learning about the transformative power of art throughout my life.

Since time immemorial, art has been used as a portal to better

understand ourselves and the world around us. At the Rubin, a museum

dedicated to art from the Himalayas, we believe art can inspire us on a

path to awakening. And in this series, we’re using a specific artwork,

the mandala, to explore this journey and the emotions that accompany us

on the way. With the help of many artists, the Rubin Museum created an

interactive space for visitors to explore these emotions. It’s called

the Mandala Lab.

But what is a mandala? A mandala is a guide. People from many cultures

and religious traditions around the world use mandalas as maps to

navigate their inner lives, including their emotions. Throughout this

series, with the guidance of scientists, Buddhist teachers, writers,

artists, and activists, we wrestle with five challenging emotions

—anger, pride, attachment, envy, and ignorance—to help us take a new

perspective on how emotions can influence our day-to-day experience…and

what they might be able to teach us if we get curious.

In this episode: Entering the mandala.

/

/

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche:

Mandala is a Sanskrit word.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche is a leading Buddhist teacher and one of the

foremost scholars and meditation masters in the Nyingma and Kagyu

schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

/

/

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche:

Manda actually comes from another Sanskrit root, which means the center.

That center actually is referring to like the core or the essence. And

so the core or the essence here refers to the essence that is of wisdom.

Wisdom that is at the core of our consciousness. That core, the essence

is the wisdom, and that wisdom is the wisdom of awakening. And then the

second syllable—la—means extracting or revealing or taking it out. So

together it is revealing or extracting the essence.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

In this inaugural episode, we introduce the mandala, better understand

what it represents and how it may be used as a guide for exploring

ourselves, each other and the world.

Like many Tibetan Buddhist art works, the mandala is a visual catalyst

that can lead to awakening. Writer, photographer, translator, and

Buddhist monk, Matthieu Ricard.

/

/

Matthieu Ricard:

Mandala is really something that is used precisely to develop pure

vision, to see all sentient beings as enlightened deities, the whole

world as what you call a pure land, which is not a distant paradise to

which you could go with a rocket or something.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Another way of picturing a mandala is to imagine you are taking a bird’s

eye view of a celestial palace, a kind of circular floor plan, with the

most important room in the very center. Around the center circle there

are four quadrants, each with a gate that faces a cardinal direction

—north, south, east, and west. In a specific meditation, a Tibetan

Buddhist might imagine themselves navigating through layers of rooms,

moving from the outside in, towards the center, towards awakening.

/

/

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche:

And so it is the circle of all aspects of our consciousness or emotions.

Another meaning is actually the center or the core refers to the wisdom

or the self-awareness. So there are like the four quadrants here that

you can see, and then the center together makes it five, there are five

primary basis what we call kleshas, or emotions, that are connected to that.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

But what do these emotions feel like? Listen to the tones, not just the

words, and these might offer a sense.

Anger

/

/

Nora:

That’s it! You’re not getting your ball for a week!

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Pride

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

You do need to respect me. I made these choices for you, I made these

choices for our family.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Attachment

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

What was really so painful was watching his passionate attachment to his

life just at the point where he was leaving it.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Envy

/

/

Sharon Salzberg:

Eww, I would be happier if you had a little bit less going for you.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

And ignorance

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

Oh, I know who these people are, and I don’t like them.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Now when we become more curious about these emotions, we can see their

true nature, see them for the wisdom they might bring us.

/

/

Matthieu Ricard:

So their true nature are the five wisdoms. It’s just a way to help us

rediscover that, is the true nature of things.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

And that’s what this series is all about. Turning emotions into wisdom.

It’s about looking at what we often find to be difficult emotions and

transforming them into their counterpoint, their wisdom.

Ruth Ozeki is a Zen priest, professor and author, most recently of, The

Book of Formand Emptiness.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

A mandala–well, it’s a map of a journey, and a journey is something that

takes place over time. It takes place over time, and it moves through

space. You start a journey in one place and at one moment in time, and

you travel through space, over time, to arrive at another place in time.

And what a mandala does is, it sort of compresses space and time into a

single image and a single moment.

/

/

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche:

That’s right. And mandala is also representation of our own true

existence, or representation of who we truly are, as an awakened,

completely free mind. And so mandala represents both the result as well

as the path that leads us to that result. At the same time, mandala is

also a representation that shows us who we have always been, from the

fundamental point of view. So therefore you can see, mandala is the

ground, and mandala is the path, and mandala is also the fruition.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

And that’s pretty cool, when you think about it. The idea that space and

time can be compressed into a single image that can be looked at and

apprehended in a moment. But then, of course, it’s not just that. Even

though you can glance up, and look at a mandala, and see it in a flash,

it really only starts to reveal itself over time again. So in order to

really see a mandala, you need to spend time with it and let the mandala

unfold and open. And that’s always interesting to me, too, because as a

maker—I write novels, and novels are a time-based medium.

/

/

Matthieu Ricard:

You don’t become a good car repairman without having a lot of

experience. So you know, hard work is necessary, and it’s good, because

you become enthusiastic, because you see what’s at the end of your

efforts. You see the fruit in perspective. But the quick fix; no, I’m

sorry, but I’m afraid it doesn’t work.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

A mandala makes a long time to make. The time that the maker spends,

that the painter spends painting, all of that time is compressed into

that single image. And then, it’s received by the person who’s observing

it, who’s meditating with it, who’s spending time with that image. And

then, the image sort of unfolds through time, over time, to the observer

as well.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

The purpose of looking at the five emotions illustrated in the mandala,

is to really see the ways we can learn from our most difficult emotions

and the role our sense of self plays.

/

/

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche:

The sense of ego, sense of ego clinging or self-centricity, according to

Buddhist teaching, is the root of all of the emotions, root of all of

the confusions, root of all of the sufferings. And so therefore

ego-centered mind always intercepts our experience. Whether it is

positive or negative experience, our ego always intercepts, and ego

always kind of hijacks our experience, our raw experience, you know?

[laughs]

We may be having a wonderful experience, awakening kind of experience,

or we may be having a really terrible experience, of anger for example.

Or wanting to harm oneself or others. But that experience usually is

hijacked by ego. So when the experience is hijacked by ego, then that

means that we have no chance, or no time to work with that experience,

but we’re working with something else. So original experience of your

anger with someone may be pretty simple, actually, but then when it’s

hijacked by ego, it becomes a totally different ballgame. Now, you’re

dealing with hijacker plus the issue with your anger, and so now you

have to rescue yourself from this hijacker.

And so it gets more and more complicated, because this hijacker has its

own agendas, its own troops, its own power, and its own game that it

brings in here. So then you can see how a very simple and beautiful

experience can get so convoluted and so far away from its original

experience.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

When that sense of self is removed, we can see the experience outside of

the categories of good or bad. We can see it just for what it is.

Matthieu Ricard.

/

/

Matthieu Ricard:

So what is pure perception? Normally when we see something, perceive

something, think of something, whether it’s people, things, we

discriminate between pleasant, unpleasant, beautiful, ugly, harmonious,

discordant, friend, enemy. So we have a very biased perception of

reality. We superimpose things to reality.

We distort reality, and that distortion is the root of ignorance that

eventually leads to suffering. So, one of the goal is to bridge the gap

between appearances and reality.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Seeing things as they are is difficult work. We all experience a wide

range of emotions and it can be hard to know what to do with them when

they come up. Neuroscientist Tracy Dennis-Tiwary-Tiwary can offer some

insight into how to shift the emotion into something that can be more

helpful to us. In the mandala, this would be where we begin to learn

wisdom from our emotions. It isn’t age that gives us wisdom, it’s awareness.

/

/

Tracy Dennis-Tiwary:

So, you’re sitting with an emotion. The very first step is you’re

calling it by its name. So you just have to make the conscious effort

of, okay, I’m going to be with this ugly feeling right now that ...and I

may not even know what it is yet. So, that’s the first thing, that

tuning in.

Then, when you’re tuning in, I think of it like a radio. When you’re

tuning into an emotion, it’s like you have a scratchy signal on your

radio. You’re trying to find a channel, but it’s like you’re going

[makes static sounds] and you haven’t found the signal yet. So, you just

keep on turning the knob. So, that’s the investigatory piece, right? So,

you’ve been with it. You’ve tuned into it. You’ve investigated it, and

then, it’s only then when you have these kinds of practices that you can

start to figure out, okay, is this useful information that the emotion

is giving me?

So, that’s the time where we shift out of all this investigation into

what I would argue is really immersing ourself in the present. Those of

us who have spiritual practices, mindfulness practices, maybe who really

love exercise, who love music, who do these things in our life that help

us really anchor ourselves in the present moment, maybe we love to take

all walks in the forest where we just admire the beauty of the world

around us, whatever it is. There’s so many ways to immerse ourself in

the present.

Then, I’d like to think of a third and final step with using emotions,

which is especially for me because I think a lot about anxiety and how

it can help us with mental health, when we take our difficult emotions.

Maybe it is anger. Whatever it is, and we hitch it to what gives us a

sense of purpose and meaning in life, then that’s when we can start to

use emotions and really leverage them for good in our life.

So, for example,maybe I’m really anxious about climate change and where

we’re going in this world. Well, I could just sit around and be anxious

about that, or I can decide, okay, well, I’m going to be anxious about

it. I’m going to try to cope with it, but the best thing I can do is to

become an advocate and to become an activist in this area that is…I

really care about it because it’s causing me so much anxiety. I care. I

have the energy to do something because anxiety gives me that

persistence and focus and drive, so I’m going to shift it towards that.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

While we’re learning wisdom from these difficult emotions of pride,

attachment, anger, envy, and ignorance, there are mandala-like guides

that can be found in our everyday lives. Other types of art can be

portals for enlightenment and awakening.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

I used to think that my writing practice and my spiritual practice were

two different things.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Again, Ruth Ozeki.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

And I was a little perplexed by that, and I think I felt a little guilty

about writing because it seemed like, especially novel-writing because

you’re just wallowing around in the realm of story. Aren’t we supposed

to be letting go of our stories? Why am I clinging to stories and, in

fact, creating new ones? I’m just perpetuating samsara here and reveling

in samsara. Surely, this must be a terrible problem. And recently, I

don’t feel that anymore at all. I feel more that writing is what I do,

and it’s my way of expressing my spiritual practice.

It is my expression of the spiritual practice that I do. And so, it’s no

longer a problem. I no longer feel there’s a separation there. And I

think that art has always been that. I think art has always been an

expression of our spiritual practice, our spiritual yearning, our

spiritual insight. It’s very inspiring. And certainly, a mandala is a

perfect example of that. But I think it applies to other media as well.

I think everyone has their own way of expressing their spiritual

practice, and it doesn’t have to be through writing novels, or writing

haiku, or painting mandala, or painting sumi-e brush paintings, or

making music. But there are so many ways of expressing our creativity

because I think our creativity is very much part of who we are as

spiritual beings. You can wash the dishes in a way that is beautiful.

You can take a walk with your child in a way that is creative, and

beautiful, and so that’s a creative expression of your…you can call it

your dharma position, your spiritual enlightenment in that moment.

We have a very, I think, sort of narrow conception of what art is. It’s

painting, it’s music, it’s poetry, it’s writing. But I think art can be

anything that’s beautiful.

I think that’s the other thing about mandala that I really love, is the

idea that the mandala really represents the interconnectedness of all

things, right? Because it’s held within this circle. And all of the

images sort of are operating in relation to all of the other elements

and images. And that is just a very beautiful and very powerful symbolic

language as well. So I really love that.

/

/

Sharon Salzberg:

Just the vast array of ways in which we are all connected is also

reflecting on the nature of mandala.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

When we come to realize how everything is connected, our minds open, our

heart opens, we feel supported and we can help others in feeling the

same. Author and Buddhist teacher, Sharon Salzberg.

/

/

Sharon Salzberg:

Someone’s mandala might include their circle of people, right? Their

circle of friends. And something I’ve said repeatedly, more so with

memorial services than with almost any ceremony, but at times with

weddings or other things as well, when I have been at gatherings with

people that have centered on an occasion in someone’s life, or perhaps

their death, it’s always amazed me how big people’s circle sometimes is.

Like, “I didn’t know you knew people from bowling.” Or, “I didn’t know

you also knit, and you were part of this knitting club.” And, “I didn’t

know you had a book club.” It’s often how I sit there in these places.

Like, “Oh, your life was so much bigger. And I was just, like, a little

corner of it. And you had all these other arenas in which you met

people, and you cared about them, and they cared about you. Look at

that. That’s such a surprise to me.” And it’s, like, the sum total of

all those many people, and influences and relationships, that would be

somebody’s mandala. That would be somebody’s kind of representation of

their life. If you were going to put everyone’s little photo, like a

Zoom screen, on a painting or something like that.

/

/

Matthieu Ricard:

I think it can lead us to a sense of, how do you say, deeper

appreciation of interdependence, or deeper kind of look, gaining a tool

to look deeper into the interconnected nature of the world, through

which of course you can’t help but to have genuine sense of love and

compassion towards each other.

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

I think the mandala really, again, is a kind of distillation of that

notion of interbeing, interconnectivity. I think it’s also a

representation, in a way, of community, too. it’s the community that is

within that circle. And so, there’s this sense of a kind of

representation, of connection, of kinship, of sangha, of the cosmos, on

whatever scale that might be. There’s a completeness to it. There’s a

kind of contained unity there. And in a way, it’s, of course, idealized,

too. In that sense, it’s quite inspirational. It inspires us to look at

a mandala.

/

/

Sharon Salzberg:

Another function of the mandala, whether you use it literally as a

mandala or not is remembering that we’re not alone. Because we can feel

so alone as we face adversity of some kind. But in truth, we’re not

alone. We’re never alone. And so, however you genuinely remind yourself

of that is a tool worth having.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

We all need tools to help us navigate the complex and dynamic world of

our emotions. But maybe the most important tool of all is curiosity,

something we all have. Over the next episodes, as we listen to

reflections on anger, pride, envy, attachment and ignorance, as we tune

in to these mind states, we can bring with us our innate curiosity and

wake up to what’s possible. As Sharon says…

/

/

Sharon Salzberg:

Everybody wants to be happy.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

And when you explore with courage…

/

/

Nora:

You’ll feel really proud because you did it by yourself.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

And you come to find that the feelings you might be scared of have so

much to teach you…

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

You’re holding the feeling, and turning it, and examining it, and

transforming it

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

And rather than be critical of our emotions, like anger, we can…

/

/

Mark Epstein:

Learn to hold anger like a baby. You hold it lightly. You hold it lightly.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Ultimately…

/

/

Ruth Ozeki:

I think these conversations about difficult emotions are the single most

important kind of conversation we can have right now to improve our lives.

/

/

Raveena Aurora:

Thank you for listening to Season 2 of AWAKEN.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

/

/

You just heard Buddhist teacher and scholar Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche,

psychologist and neuroscientist Tracy Dennis-Tiwary, Buddhist teacher

and author Sharon Salzberg, author, photographer, and Buddhist monk

Mathieu Ricard, Zen priest and author Ruth Ozeki, ten-year-old Nora

Wood, and activist and author adrienne maree brown.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Art with Dawn Eshelman, Tenzin

Gelek, Jamie Lawyer, and Christina Watson. The series is produced in

collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC including Tania Ketenjian, Emma

Vecchione, Philip Wood and Jeremiah Moore.

Music produced by Alexis Cuadrado and Hannis Brown. With some additional

tracks from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 2 is part of the Rubin Museum’s Mandala Lab, a multiyear

initiative generously supported by 28 donors and sponsors. Lead support

is provided by the Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation, Barbara

Bowman, The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, Rasika and Girish Reddy,

Shelley and Donald Rubin, and the Tiger Baron Foundation.

/Public funding is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural

Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the New York State

Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and

the New York State Legislature./

You can continue the conversation by following us on Instagram at

@rubinmuseum. And if you’re

enjoying this podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to

podcasts, and tell your friends about the conversation you just heard.

This is episode 1 of a 7-part series inspired by the Mandala Lab at the

Rubin Museum—an immersive space for social, emotional, and ethical

learning. Come explore the Lab in New York City, or in one of the

installations that is traveling the world. To see the Vairochana Mandala

which inspired the Mandala Lab and this season of AWAKEN, visit

rubinmuseum.org/awaken. We look forward

to seeing you soon. Thanks for listening.