This week, we are thrilled to be speaking to author Julia Boyd. In May of this year, Julia released the wonderful A Village in the Third Reich, an eye-opening account of how the rise of fascism and Hitler marked the lives of a small community nestled in the Bavarian mountains. It is a fascinating and eye-opening read, and a great example of how even the most well-known parts of history can always find a way to surprise us.

Show Notes

Purchase A Village in the Third Reich here

(1:11) Julia Boyd Introduction

(1:57) Julia's Childhood

(9:04) Julia's Interest in History Writing

(21:15) The Last Book Julia Read

(23:49) Weaving a Historical Narrative

(29:55) The Books that Changed Julia's Life

(36:31) Music & A Village in the Third Reich

(46:35) How Julia Fell into Writing

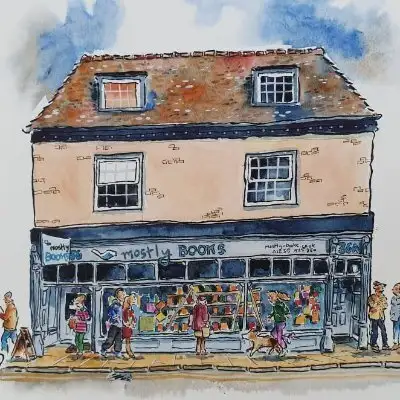

The podcast is produced and presented by Jack Wrighton and the team at Mostly Books. It is edited by Story Ninety-Four. Find us on Twitter @mostlyreading & Instagram @mostlybooks_shop.

Meet the host:

Jack Wrighton is a bookseller and social media manager at Mostly Books. His hobbies include photography and buying books at a quicker rate than he can read them.

Connect with Jack on Instagram

A Village in the Third Reich is published in the UK by Elliott & Thompson Limited.

Books mentioned in this episode include:

The Famous Five by Enid Blyton - ISBN: 9780340681060

Father and Son by Edmund Gosse - ISBN: 9781784874391

Dear Life by Alice Munro - ISBN: 9780099578635

To find more titles, visit our website

Creators and Guests

What is Mostly Books Meets...?

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets, a podcast by the independent bookshop, Mostly Books. Booksellers from an award-winning indie bookshop chatting books and how they have shaped people's lives, with a whole bunch of people from the world of publishing - authors, poets, journalists and many more. Join us for the journey.

Sarah Dennis 0:24

Welcome to Mostly Books Meets... We the team at Mostly Books, an award-winning independent bookshop in Abingdon. In this podcast series, we'll be speaking to authors, journalists, poets, and a range of professionals from the world of publishing. We'll be asking about the books that are special to them, from childhood favourites to the book that changed their life and we hope you'll join us for the journey.

Jack Wrighton 1:11

On the podcast this week, we are thrilled to be speaking to author Julia Boyd. In 2017, she released the spellbinding Travellers in the Third Reich, a history of the rise of fascism told through the first-hand accounts of those who had travelled through Germany. It went on to become a Sunday Times top three best seller and to win the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for history in 2018. In May of this year, Julia released the wonderful A Village in the Third Reich, an eye-opening account of how the rise of fascism and Hitler marked the lives of a small community nestled in the Bavarian mountains. It is a fascinating and eye-opening read, and a great example of how even the most well-known parts of history can always find a way to surprise us. Julia Boyd, welcome to Mostly Books Meets.

Julia Boyd 1:56

Thank you.

Jack Wrighton 1:57

Thank you for joining us. Now in our podcast, we always sort of start by going back to the childhood days of our guests. Now am I right in saying you grew up in London as a child, but also spent quite a lot of time in the Lake District?

Julia Boyd 2:12

Yes, that's right and actually, my father was in the Navy. So my very early years was spent abroad in Malta and South Africa, but most of my childhood was in London, but as you rightly say, with large chunks of it spent up in the Lake District, which of course is absolute paradise. It was a wonderful place to be as a child.

Jack Wrighton 2:36

And was reading always a part of your life as a child, were you much of a reader then?

Julia Boyd 2:44

Well, I was trying to remember. Yes, I did like reading very much, but I'm afraid my choice of books will probably not be approved of. I was a great fan of Enid Blyton. Secret Seven, Famous Five, and Mallory Towers, which like lots of other little girls of my generation, I think, made me long to go to boarding school. That seems odd, doesn't it? But then I graduated from Enid Blyton to Biggles by W.E Johns, I was really a tomboy, and I didn't like dolls, and I thought most girls things were rather silly and so I absolutely adored Biggles. I don't know, maybe he's not familiar to some people listening to this, but he was a first world war pilot, who flew Sopwith Camels and had all kinds of incredible adventures. So yes, then from Biggles, I think the first book that I read, that was a sort of grown-up book and chilled me to the bone was Nevil Shute's On the Beach, which was published in 1957 and I think I read it when I was about 13, perhaps 14 and it was all about people in Australia waiting, there'd been a great nuclear catastrophe and the people in Australia were waiting to die, basically and it was the first time in my life that it struck me that, you know, that things wouldn't necessarily go on the same as ever, and these terrible things could be lurking around the corner. So that was rather a growing-up experience for me.

Jack Wrighton 4:22

Yes, I think it's an interesting point in any person's life, is that point where you come across a story, you know, for some people today, it might be through books, or it might be through film or a TV show, but something that, you know, maybe at the time is quite scary and quite arresting? But even if at the time it's a little bit distressing, you tend to find actually, as time goes on, people sort of speak about that moment almost fondly as if they realised it was a bit of a turning point.

Julia Boyd 4:54

It's very much I think, a part of growing up and sometimes is realisations come upon us slowly. But I think for many of us, it is through the experience of reading something as in my case, Nevil Shute's On the Beach. But you're absolutely right. It's a very important moment and the whole process of growing up when you suddenly realise the world is not quite the safe place you thought it might have been.

Jack Wrighton 5:19

Yeah, absolutely and you said, you know that some of your reading choices may not be so popular today, but Enid Blyton I can say from both this shop, Mostly Books and where I've worked previously, it still very much sells, you know, whether it's Malory towers, the Famous Five, the Wishing Tree, you know, it's all...

Julia Boyd 5:42

Well, yes, I mean, I'm a great subscriber to the belief that, in a way, it doesn't really matter too much what young children read as long as you can get them reading and of course, in today's world with all the screen stuff, it's probably more of an uphill struggle. But anything that catches a child's imagination, and reading has to be a good thing.

Jack Wrighton 6:06

Absolutely, absolutely and yes, we always will always say that at the shop that you know, it's lovely to suggest to a child, you know, the books that you enjoyed when you were younger, and sometimes that works. But also it's important that they can choose the books for themselves as well. If it grabs their interest, then brilliant.

Julia Boyd 6:26

One thing I enjoy most is taking my grandchildren to a bookshop and it's lovely, watching them choose their books.

Jack Wrighton 6:34

Yes, absolutely and it's okay. I wouldn't expect you to remember sort of titles and things. But, you know, do you look at the books yourself and you know, think about how I don't know, how children's books have changed, or...?

Julia Boyd 6:47

Yes, and I think they've got, I mean, I think there are wonderful books out there, there's so much to choose from, and, of course, a lot of them, perhaps, are more consciously trying to put forward liberal ideas or, you know, to deal with racism and all these things. I don't think any of that was apparent when I was a child, I think it was, you know, I grew up in a very... London was very white and, you know, there was you couldn't get a decent cup of coffee and pasta, as far as I remember. It was rather nasty-looking sort of maggot things and brilliant orange sauce in a tin. I'm 73 now and so we're talking about a very different world, but I think, I don't know, I think children's books are really amazing today and I think today's children very lucky. As long as one can wean them off their screens.

Jack Wrighton 7:46

Yes, yes, of course. The forever battle against the screen. Yes, yeah. I know many adults struggle with as well with themselves.

Julia Boyd 7:58

Me too, I mean, especially if you're writing books, you can find that at the end of the day, actually, you know, it's really the last thing you want to do if you've been on your screen and writing to sort of read a book and I very ashamed of how little I've read, since I started writing myself, it's really only on holiday and you know, when you're sick or something that I can really get stuck into a proper book, otherwise I tend to flit around, it's not something I'm proud of, but I suspect it happens to quite a lot of us.

Jack Wrighton 8:30

Yes, absolutely. I think because reading does, the wonderful thing about reading is it as opposed to let's say watching something on a screen. It's a bit of a, well not a dance, but a collaborative effort. You know, the writer has written the words down, but you make the pictures in your head, you know, so...

Julia Boyd 8:48

Absolutely, which is why I love listening. I really never watch television, but I do listen a lot to the radio and I love listening to radio drama, because you can direct the play yourself in your head and summon your own images. So it's sort of the same thing then isn't it?

Jack Wrighton 9:04

Absolutely and you know, it's that's an active thing. So it means yes, if you've had a long day of you know, doing anything it can sometimes require a mustering of energy, but as you say, absolutely it is. It is always worth it and of course, for those who come across your work now whether with Travellers in the Third Reich or your latest one, A Village in the Third Reich, we obviously know you for your history, writing. So was that always an interest?

Julia Boyd 9:38

Yes, I always loved history. I mean, it was absolutely the subject that I liked best at school. But I certainly never thought of writing history. I mean, a complete accident. Actually, when we were in Japan, we lived there for a couple of... nearly four years in the mid-90s and I was persuaded to write a book about what seemed to me a very unpromising subject, a missionary, a Victorian missionary, who had built leprosy hospitals in Japan and some Japanese people were very keen that I should write about this in English and I said, well, you know, I'm not a writer, I'm not a historian and I think we might have problems getting it published. But anyway, to cut a very long story short, it happened and it introduced me to the delights of hunting in archives, of trying to take quite a big slab of history. In this case, it was really the late 19th century and early 20th century in Japan, and then weave into that some, some individual experiences and so I had an enormous amount of fun with that, and it did get published and then when I went to, we spent 10 years in Cambridge, after we left Japan, and had enjoyed the whole process of writing this book about the missionary so much that I thought, well, here I am in Cambridge, I must try and do it again. So then I wrote about the first woman doctor who nobody really ever heard of, but I thought anybody who calls herself the first woman doctor must be interesting. Yeah and again, for me, the pleasure of writing about Elizabeth Blackwell, who she was called, was spending so much time in archives looking at primary material, I mean, that's where I get my kicks from, is finding out what people wrote there and then, you know, relating it, as I say, to the bigger picture. So that's really how I got started and I never in a million years, would have expected to end up writing two books about the Third Reich, because I mean, that really is part of history that's probably been written about more in my life time than any other and it certainly wasn't my idea. But once I got going, and I found out how much material there was. Then I got the sort of wind in my sails, but it was, I would never have had the courage or arrogance to suggest that I could write about such a massive period of history. But I think there is a real market now for what some people describe as micro-history or grassroots history or whatever you're like, in a sense, going back to the Third Reich, we've been through all the great battles, and the generals, and the heroic stories and so on, of which, of course, there are so many, but I think, in today's world, people perhaps are quite interested in, in the stories of... I hate that phrase, ordinary people. But you know what, I mean, people who are not generals, and not heroes, but had to get through this ghastly event somehow and I think the question I always ask myself, especially in regard to the Third Reich, and the Nazis and all the unspeakable horrors that happened, there is, well, how would I have acted? What would I have done? And I think, you know, especially with the Nazi period, it's such a black and white period, you think of it being very clearly divided into good and evil and I think I'm always interested in exploring the grey areas, because, as we all know, especially me at my grand old age of 73, life is really full of grey, and one only has to look at one's own life and emotions and evolution, to realise that, you know, one changes one's views as one gets exposed to other ideas and different people and so I am an explorer of the grey area, I think.

Jack Wrighton 13:42

Yes, which, you know, makes for makes fascinating reading, I think, I think everyone who reads that any particular period in history, but I think, particularly with the Third Reich, you know, does have that question at the back of their mind of, you know, what would I have done if I had been living... or if I was living in a country in which, you know, something like that was happening? Who would I become, or what, what would I do? And I think that's particularly I mean, reading a village in the Third Reich is something that really stands out is it's easy to when you're reading about the Second World War on that sort of big level of you know, about the battles, as you say, to yes, think about it in very clear terms of, you know, there were the good guys, and there were the bad guys. But then when you look at this village, you know, you soon realise that, as you say, just how much grey there was and how many people who on the face of it, you would think were, you know, they were party members, they could be sort of, you know, seemingly quite sort of signed up Nazis but actually also do things that seem completely out of character.

Julia Boyd 14:53

Yes. And I think also another fact, bear in mind is a lot of people supported Hitler and the Nazis because Germany was absolutely not for six after the First World War. I read a lot of letters that Quakers who were out in Germany immediately after the First World War, and they were travelling around on trains, talking to ordinary Germans and the letters are absolutely fascinating because the Germans were... many of them were starving, they were immersed in grief, because of the loss of family members and so on. They had an absolutely hideous time. But what's so interesting from these letters is that what comes through is how it was their pride, it was the loss of pride that mattered more to them, than the hunger, the grief, the probations and so, I mentioned that because I think it helps to explain why so many Germans supported Hitler, at least in the early 30s, or when he first came to power, because he seemed to be restoring their pride putting Germany back at the top Table of Nations and that really mattered to people and so a lot of people who might not have liked it to very much personally or not approved of all the things that the Nazis were doing, but that mattered to them and as long as Hitler seemed to be restoring Germany's pride, then they would go along with it. But of course a lot of them also thought that once he was in power, he would sort of calm down, that the anti-Semitism and so on, would gradually fade away. Of course, as we all know, that actually only got worse. But people didn't know that and so I think a lot of people who were enthusiastic, quite soon realised, wow, what have we done. But by then, you will know the moment Hitler was in power, he screwed down the nation, he screwed down people. So anybody who was brave enough to pretest would end up in a concentration camp, or their job, and then their family would suffer. So it was... you know a lot of people say, well, why didn't the German stand up to Hitler? So I think it's a much more nuanced picture, certainly than the one that I grew up with. I'm not I mean, other people may have worked this out long before me, but certainly, for me, it was a realisation, just, you have to think about it in stages, we have to think of people's attitudes to the Nazis and Hitler evolving, I think. But I think the real point is that by the time people decided or realise, as a lot of people did that, how awful the Nazis were and actually, I should make a distinction here, because people tend to, to remain very loyal to Hitler, may well have hated the people around him and they always blamed the people around him for what went wrong, that Hitler had a sort of godlike image for many people. Nevertheless, everyone knew that if you started bad-mouthing, Hitler, or the Nazis or anything, you put your life at risk and your family at risk. So I think those are important things to remember when judging people and their behaviour. During the third, right?

Jack Wrighton 18:04

Yes, we have the benefit of hindsight, we know the endpoint, it makes me think of that analogy that people use of you know, that supposedly, if you, if you try and put a frog in boiling water, it will jump out. But if you pop it in water, and slowly turn up the heat, it will remain there indefinitely, even as the heat gets to that kind of boiling level and I think, I think.

Julia Boyd 18:31

A very powerful analogy I think, yeah.

Jack Wrighton 18:31

Yes and I think, you know, it's, it's good to remember that because it's easy to, you know, with hindsight to go, oh, no, I, you know, I would have I would have done things differently and that that applies to, you know, going beyond, you know, the Third Reich, just anything really.

Julia Boyd 18:49

There is a great tendency and I suppose it's completely natural, that we judge history by today's standards and you have constantly, which is why I suppose I go on trying to write the history that I do, you have constantly to put yourself in the mindset of people then who were subjected to a whole lot of different mores and ideals and ways of life and attitudes to the ones that we're used to and even in my lifetime, when I think, you know, it seems to me completely inconceivable that I was 20 years old, I think by the time homosexuality was made legal, I mean, so you know, history changes rapidly and yes, people's attitudes do evolve, they may stay the same people fundamentally but we're all little sponges and we all soak up in a way what's going on around us, some people are very brave and they stick their heads up above the parapet and they have clear foresight, but an awful lot of us and I would have to include myself in this just tend to sort of, you know, trundle along with with with what's going on at the time. So I think what has bad out in mind very strongly.

Jack Wrighton 20:01

Yes, I think I like the sponges analogy because it's true. Even you know, even since I was, you know, a child, I think politically how things have changed or, you know, certain opinions or views.

Julia Boyd 20:16

Same-sex marriage is another one. When I was, you know, in my 20s, or even my 30s Yes and now, you know, one can't imagine what the world was like before it.

Jack Wrighton 20:28

Yes. Yeah. Because once it happens, you know, it's, it's quickly accepted. Yes. It's, it's always Yeah, always good to remember that, you know, things that things are always on the move and that's a good thing. But you know, that it means that the moment you're looking even sort of 15 years or 20 years, and then going further and further back that you're looking at the landscape has changed.

Julia Boyd 20:52

So I think it's worth remembering that not not that I want to whitewash past sins and horrors. But I think that in terms particularly of the general populations reaction to certain things, it is worth remembering that and how they grew up with very different set of ideals and modes of behaviour from what's current today.

Jack Wrighton 21:15

Yes, absolutely. I want to... we'll go back to the book and the process a bit later on. I wanted to ask about your reading. You know, today, going from your childhood now, now to the present. What type of books that you enjoy now, or books that you've read recently that you have sort of particularly enjoyed?

Julia Boyd 21:39

Another terrible sin to confess is that I don't read an awful lot of fiction. But I get sort of terrible guilt about this from time to time. So actually, the last book I read in the summer was Alice Munro's Dear Life, a series of short stories, which I absolutely loved. I mean, I think what I get from her writing is her ability to show that, you know, quite sort of what seem from the outside, quite straightforward and simple lives actually hide all this high drama and that, you know, even if you're living somewhere in Canada, which is not a country, I know, well, you know, you can still go through tremendous ups and downs and dramas and how she puts at the heart of her book, you know, sort of relationships and love and marriage and this takes so many different forms. I mean, I suppose that's obvious, but she somehow does it in a particularly brilliant and striking way. So I certainly and I think the short stories I mean, she has often been described as the Chekov hasn't she have, of modern writing and I love checkoff and so yes, she's the last book I've read and I'm not very good at reading novels, because quite often start off and then get bored or interrupted and I've occasionally joined book clubs, but then I find myself reading books that I don't particularly want to read and I think, why am I doing this? And then I've forgotten it anyway, a couple of weeks later, so, but I do read, I've always read a lot of history, obviously and but I do find that for the last 30 years, I've mostly been engaged in trying to write a book myself, and I tend to do an awful lot of reading around that. My reading is, as I said, earlier in this conversation, I feel rather ashamed of how little I read in this programme, this podcast is encouraging me to turn over a new leaf and get reading a lot more.

Jack Wrighton 23:49

No, but of course, you know, as you know, there's no whether it's fiction, or it's nonfiction, you know, there's no hierarchy of, you know, hierarchy of reading and, you know, as you say, a big part of your process and it sounds like the part that you enjoy the most is the archival, you know, going through the archives and one thing that struck me when reading A Village in the Third Reich is thinking in terms of the work is you must start off with, you know, the amount that you read for such a project must be huge and I imagined a lot of the skill or the difficulty becomes then editing that down and creating a narrative from that.

Julia Boyd 24:39

That's so right Jack, I often describe myself more as a weaver than a writer because it's, it's the real sort of challenge doing the sort of history that I've tried to do is weaving all this individual experience into the world story and to do that without sort of sounding like you're doing clanking changes of gear is, is really hard. Yes, but I sometimes think of myself as a sort of Miss Marple, because a lot of it is... and that's perhaps why come the evening, I don't sit down and read as much as I'd like to because I spend so much the day, chasing things, looking at things, reading bits of books, following them up, trying to track down the papers, or the personal view and so that that is enormously satisfying, especially when you come across something and I think almost my favourite way of spending a day is to end up in some obscure public records office somewhere like Wigan or somewhere, and you wait, and they bring you your box, which is sometimes it's an old cardboard box tied off the string, and you're pretty sure that nobody's looked inside that box, since it was deposited in the archives, and you open it up, and you have no idea what you're going to find. It's like a sort of time travel to, if you're looking at what people wrote there, and then they haven't filtered it with history and see, it's like a time travel. It's like a snapshot and some of it is very crass, some of it is quite boring, and lots of it is repetitive, but you end up with a real sense of the period you're reading about and I don't think there's any other way that does it so completely, at least not for me, anyway.

Jack Wrighton 26:31

Yes, it must be a thrill, I think, particularly if you're looking at something, you know, handwritten. To think that, you know, that you're probably actually one of the few people who have sat down and taken the time to read through that and to also see the, you know, these people living through events that have I mean, for us now, they've almost entered the realm of mythology, almost, you know, the way sometimes, you know, the, let's say, the Second World War is spoken about, you know, because there's been so many films, there's been so much kind of entering the kind of collective narrative of, you know, of the country or you know, of the world, you notice that you then suddenly see a letter where someone's going about their very sort of mundane life while all this is going on.

Julia Boyd 27:24

Yes, well, I wrote a book about the foreigners who lived in Peking in the first half of the 20th century and of course, they would sort of sit down once a week, to try and summarise all the extraordinary things that have been happening in Peking and write back to their families and that, that has sadly gone now. I mean, you know, I mean, this is a subject people talk about a lot, but it's really quite hard to know how this kind of history, there's so much material, there's so many emails and so much on film and so on, that it's this sort of rather narrow window of history where people dependent still on communication via letters, because they tried to summarise their lives in a way that nobody would do today with the instant email or text or whatever it is that people use. So yes, I think it's a... it's not great history, but I think it has its role in helping people understand really what it was like to be there, then in a particular place at a particular time.

Jack Wrighton 28:29

Yes and do you think, sorry, it's just a very interesting thought that, you know, someone doing your job, and let's say, you know, 80 years time, who's trying to look back on today, for whatever reason, we'll have a much more difficult task, because you know, the nature of digital communication means that while it's instant, and it's numerous, you know, we, we communicate within the space of a day, multiple different ways on multiple different platforms now, but of course, that lasts really only as long as the technology does and can quite easily be...

Julia Boyd 29:06

There have been some very good projects, certainly, at the British Library, I think, and at Churchill college, to record oral history and so that that will be a big resource. But that again, it's somebody sitting down to do a formal presentation about their life or their job or whatever it is. The glorious thing about the sorts of research I do is these people were not writing for posterity, they were just writing about the world as they saw it at that particular moment and so that I think will be lost because I didn't know perhaps people will leave their hard drives to archives, but it gives you a very different kind of take on history to the one that I've been absorbed with over the last couple of decades.

Jack Wrighton 29:50

Of course, yes, yeah, I suppose it will just it will adapt, won't it?

Julia Boyd 29:55

It always does.

Jack Wrighton 29:55

Yeah, it's yeah, it's, you know, no matter how much changes, adaption is, is the key to that. So I have, it's a rather big question and I always say on every podcast, I always feel bad for asking this question because I feel it's one I would struggle to answer myself and it's a book that changed your life.

Julia Boyd 30:20

Well, guess I mean, I thought she, when you told me that, you're going to ask me about that and also, the book that everyone should read. I've actually given it all, quite a lot of thought and I'm slightly embarrassed to say this, but the book that quite literally changed my life, and it's not a book I would seek to recommend to anybody. But it was the first book I ever wrote called The Story of Furniture. I was working in the furniture and woodwork department in the V&A, and the telephone rang one day, and it was Hamlin saying, We've got this book, we've got all the photographs. we've sold it, but we have we forgot to ask anybody to write it. So I said, Oh, I'll do that and it's not a particularly good book and I'm certainly not plugging it. But the reason it changed my life was because Hammonds paid me the princely sum of £400, which back in the 70s was worth a lot more than it is now. But instead of paying off my debts, which is what I should have done, I blew it all on going to China and this was in 1975, when it was almost impossible to get to China. So Cultural Revolution. Yes. Where I met my husband, who is working in the British Embassy there. So that really did quite literally change my life. Yeah. But you also asked, and perhaps I'm jumping the gun here. But what is the book that everyone should read and that that's a tough question and I haven't given it quite a lot of thought came to the conclusion that was a book again, I read when I was quite young and have returned to several times was Edmund Gosse's, Father and Son. Edmund Gosse, as I'm sure your listeners all know, was a critic and writer. But I think most of his writings are probably fairly obscure now, but he is definitely remembered for this book, Father and Son, because he grew up in a very religious sect. I think it was a kind of brethren and his parents were, obviously good people and you know, he wasn't treated cruelly or anything and he obviously had a deep affection for his father, but it was such a restrictive and unnecessarily unimaginative childhood and I think, his own words, and I think this is why I feel so strongly about this book, because it's so relevant today and I think he says it much better than I could. He says, Let me speak plainly after my long experience. After my patience and forbearance, I have surely the right to protest against the untruth. That evangelical religion or any religion in a violent form isn't a wholesome or valuable or desirable adjunct to human life. It divides heart from heart, it sets up a vein chimerical ideal in the barren pursuit of which all the tender, indulgent affections or the genial play of life, all the exquisite pleasures and soft resignations of a body, all that enlarges and calms the soul are exchanged for what is harsh, void and negative. It encourages a stern and ignorant spirit of condemnation, it throws altogether out of gear, the healthy movement of the conscience, it invents virtues which are sterile and cruel. It invents sins, which are no sense at all, but which darken the heaven of innocent joy with futile clouds of remorse. So I think what I'm saying is I'm not anti-religion in any sense, but I think it's so important. I mean, I hate extremism in any form, and certainly when it imposes with violence, a mode of living on others. So, I mean, that's stating the obvious, but, you know, it's a message that can never be said enough, really, in today's world.

Jack Wrighton 34:12

Absolutely. Thank you for reading that. Oh, that was a beautiful quote.

Julia Boyd 34:16

Sorry. It's rather a long quote.

Jack Wrighton 34:18

No, no, no, it was no, it was wonderful.

Julia Boyd 34:21

He puts it much more eloquently than I could.

Jack Wrighton 34:25

No but it's beautifully put. It's a great example of how, you know, in, in books, you know, doesn't matter when it was written that you can find those snippets that just they speak to all times and all places, and a message like that never ages, you know, it remains true.

Julia Boyd 34:45

And of course, there are so many books that have had that. I mean, that's the glorious thing, isn't it about reading is that you can pick up a book published in the 16th century and you'll suddenly hit upon this truth that is just as relevant today as it was when it was written.

Jack Wrighton 35:03

You know, absolutely. I mean, I find that you know, when I reread something like Jane Austen, and I think, you know, some of the characters in that and you think, well, I've met that person, you know, they...

Julia Boyd 35:14

She understands human nature, actually and human nature doesn't really change. It has different clothes on but she absolutely got it and Trollop did, of course, as well, I think.

Jack Wrighton 35:25

Yeah and it's just that wonderful thing of, you know, thinking that coming across a character from Yes, a completely different century, which could feel like a, you know, a foreign country, as they say, you know, that was a foreign country, but actually, you think, no, I've met that person in the shops just yesterday. I went to school with that person, you know, it's a, yeah, it's one of the wonderful things about...

Julia Boyd 35:50

One of the things that unites human beings across the ages, you know, it makes you feel you're not necessarily live in our own little slot. But reading and for me, also music expands it. So that one feels this connection with the human race. You know, Philip Larkin did that very well and he, in that wonderful poem about being in a church, and I think he was an atheist, but it you know, it was that sense of linking in with generations and generations of people who have knelt in that particular church and yes, of course, books. Above all, help us do that and shake hands across the centuries or whatever.

Jack Wrighton 36:31

Yes, yeah, absolutely, and yes, you've meant you, you'd mentioned previous to me not on this, recording that, that, yes, music is another great, a great passion of yours. By the sounds of it.

Julia Boyd 36:44

Yes. I spend an awful lot of time at Wigmore Hall, I'm lucky enough to live quite close to it and, you know, there again, your sense people's sadnesses and tragedies and joys, you know, you can sort of unite and hear the moment the composers like Schubert, it's almost like listening to an autobiography, you can feel the resonance that he's going through. And so I do get a lot of pleasure out of music.

Jack Wrighton 37:18

Yes and there's the there's a wonderful, well a very interesting part in, in A Village in the Third Reich where, you know, music is important to the soul, but it's it's also a form of, you know, it can be used in lots of different ways.

Julia Boyd 37:36

Propaganda, yes.

Jack Wrighton 37:37

Yes, propaganda. It was just very interesting reading about, you know, the villages, their local sort of band or orchestra, as it were, you know, the struggle that happened there, where they wanted them replaced with these professionals that would play, you know, kind of Nazi music.

Julia Boyd 37:57

Yes, exactly. I'm glad you picked up on that, because I thought it was a rather touching story and the villagers are there, they still on the whole, at that stage approved of Hitler, we're not going to be kicked around by this nasty little upstart Nazi mayor. It was really interesting how they could be supporting Hitler still, but we're not prepared to give up their independence. So that was, I thought, an interesting insight into human nature.

Jack Wrighton 38:23

Yeah, absolutely and, you know, you see that throughout the book, you know, this, this small village, which, you know, it had it had it some, you know, certain systems in place, like the common council was it was it called?

Julia Boyd 38:38

Yes, the village council, yeah.

Jack Wrighton 38:38

You know, and the common land as well, that had to be, you know, and you realise how, you know, all of these things that you think, oh, you know, that you would think, without reading a book like this, or, you know, well, Surely these people then wouldn't be up for, you know, to totalitarian Hitler. But of course, they didn't know that would be the case.

Julia Boyd 39:01

And then when the reality hit them a few months later, in the shape of this very idealistic Nazi mayor who was completely subscribed to national socialism and yes, he had to implement Hitler's very rigid rules about conforming to national socialism, because the villagers didn't like it one bit. They voted for Hitler, but that didn't mean that they'd signed up to her giving away their autonomy.

Jack Wrighton 39:28

Yes and so a good lesson again in the fact that you know, again, we have hindsight but of course, you know, for them, you know, they have no reason necessarily to believe that...

Julia Boyd 39:42

Look into a crystal ball, wouldn't that make life easy?

Jack Wrighton 39:44

Exactly and it's wonderful to read as well about the... you know, because I think we know about, you know, people in the resistance and the I think many people maybe I'm more alerting my own ignorance here. But I think many people would think that anyone who resisted in any way would have ended up either leaving the country or would have ended up in one of the camps somewhere. But of course, you realise that, you know, that there were these people that in their everyday lives even if they were finding just small ways, you know, I think of the headmaster at the local school, you know, found small ways of kind of alerting, at least to maybe those in the know that, you know, know this, I don't agree with everything here, or finding ways of, you know, fighting the want to, I think, use a line earlier on in the book about, you know, that Nazism wanted to, you know, work its way into every aspect of life and of course, people did resist that.

Julia Boyd 40:50

Yes, no, I think that, to me, that was one of the interesting aspects of doing the research of this book is to see that it was actually possible to be a paid-up member of the Nazi Party, but actually not being Nazi at all and of course, it was a subtlety that when the Americans occupied Bavaria, immediately after the war, well the French were there first for a few months, but then the Americans took over and, of course, it was, you know, they'd seen the soldiers coming there and occupying Germany had seen all the Nuremberg rally films, they just fanatical Germans. So they assumed that there were Nazis behind every tree and of course, there was an element of the SS, particularly, and you know absolutely fanatical Nazis, who were there right at the end, they were actually fairly small in number, but it was enough to frighten the Americans, who were very nervous about, you know, Nazi resistance after the war ended. So it is interesting to see these multifaceted reactions to the Nazis and how their villages coped, and I think, though, they found it very hard to really face off at the end to the whole question of national guilt. and I think they tended to concentrate all their energies on trying to get their lives back together again. So it took perhaps longer than it should have done for people to face up to the enormity of what they had signed up to when they voted in Hitler and the National Socialism. But I think since then, Germany has done an absolutely incredible job and that's beyond question. They've been really impeccable. But I think there is still more work to be done. I'm not saying this, just because I and my collaborator, Katty Patel, happened to have produced a book about a village, but I think that there is a lot more work and research to be done at the village and time level, because every small community had its own reaction, its own set of circumstances. So it's probably a quite a rich field of research.

Jack Wrighton 43:15

Oh, absolutely. I mean, you know, yeah, just to think of all the individual stories out there. You know, it's probably endless, you know, probably endless research could go into that area, even when you just think of the stories that you hear growing up, you know, I think of my grandmother, who lived through the war, you know, every family has its own individual story, which...

Julia Boyd 43:39

Well of course, it's getting fainter now. It's getting on for 80 odd years now, since it's so, you know, that's where these letters and, and memoirs, and some of them often in people's attics or wherever, they suddenly become much more important because as people die, my mother died last November, aged 101 and she had actually spent seven months in Germany, in 1937. She was studying, she wanted to study languages, and she started in Germany. But I found her diary and you know, it was so interesting. She was too old to remember in I mean, I knew about it roughly. But it's an example of how important it is to, to conserve letters and diaries. Often people think, oh, god Aunt Hetty's letters in a suitcase. I don't know what to do with them. Let's get rid of them. So I would plead with anybody who is faced with knowing what to do with some relations papers. Before you chuck them. Just go and talk to your local archive and see if it's something that they're interested in, of course, and anyway, even if you want to keep the you can always digitalise things now, so you can always keep your own record, but I do think it's one worth preserving letters, diaries memoirs, in an archive if you possibly can.

Jack Wrighton 45:06

Yes. You know, we don't always know that we might be living through interesting times or that what we have to say about that is interesting. You know, and it's easy to think your own family member, oh, you know, they were just an ordinary you know, this term ordinary person.

Julia Boyd 45:24

Oh, Jack that is such an important point. Because even something as mundane as a shopping list, you know, in 100 years time is interesting. I'm very glad you made that point. It's a really important one. So it's not for us to judge what's interesting, but I would just recommend that people try and find a safe place to deposit such things where they will be preserved for the future.

Jack Wrighton 45:49

Absolutely and one thing I want to ask as well as just, you know, how has it been in the sense of, you know, because Travellers in the Third Reich, it was actually interceded with me starting as a bookseller, I started in 2017 and, you know, it was a huge hit, you know, it, you know, it did very well, I'm just always interested in, you know, speaking to authors, what was that like, for you on your side, you know, having this because, you know, you had been in the archives, you had done all the work and of course, people don't always realise that when they're reading a book, they're actually already on a timeline that started years before. How is it then to suddenly realise all these people are reading it?

Julia Boyd 46:35

Oh, unbelievable. As I say, I fell into writing by accident. For me, it was a wonderful, wonderful hobby. I mean, I was very pleased I got my books published and, you know, even got the occasional review. It never occurred to me, I would ever move on from that at all and I was perfectly happy with that. I wasn't expecting great success or anything. So travellers completely took me by surprise I had, I wasn't even I'm still gasping. But I think it's less to do with me, I think it's much more to do with the fact that it brings history, that approach, I'm not saying I'm particularly brilliant at it, but I think that the approach is one that is probably found it's time. It's something that, you know, resonates with people and so maybe it was just luck and my timing was just lucky and I could not have been more astonished, I still remain Tokyo's tarnished. That it has done well. So, you know, especially it's quite old now. You don't really expect to start having a success when you're in your late... whatever it was. So yeah, it was delightful and I can't pretend I wasn't very pleased.

Jack Wrighton 47:55

Yes, of course, of course. Absolutely. I mean, that's the wonderful thing. I think, again, particularly about writing, you know, from all the people I've interviewed on this podcast, is, you know, obviously, if you're something like a sports person, everything's obviously going to happen in the sort of the first kind of quarter of your life that people can be writing for years, and then suddenly something pops up, and they think, oh, my goodness, everyone's reading this or, or some people don't, you know, yeah, don't start writing until later on until they've had families and you know, things like that.

Julia Boyd 48:27

As in my case, I mean, the only thing about it, which is the downside is that I and I feel this with Travellers as much as anything else. I can't bear to read anything written because also it's, it's there, you can't, I'm a great editor, I go on fiddling and fiddling forever and ever, and suddenly, it's there and you think, Oh, God, I wish I hadn't written that, or I wish I was on there or you know, and I'm sure everybody who publishes a book feels the same way.

Jack Wrighton 48:55

I mean, I will, I will perfectly admit I was this morning, I was listening back to one of my podcast recordings, I just wanted to check something and I think with any anything you do, if it's your words, whether it's coming from you personally, in a recording, or whether it's written down, there's a very particular type of pain and sort of embarrassment, that comes from you know, even if it's something that you're proud of, you're still there's a part of you that thinks, oh, why did I say it like that.

Julia Boyd 49:24

Yes, exactly, or I could have done it, but I find it so interesting. I don't know whether you'd agree with this Jack. But, you know, when it comes to actual writing, I find that I often spend the longest wondering whether to use the definite or the indefinite article or which preposition to use, or fiddling around with little tiny words to get the flow right and sometimes a sentence which when you read it, in the book, it looks perfectly sort of unobtrusive, normal sentence and I remember oh god, it took me a week to get that one, right. Do you ever find that?

Jack Wrighton 49:59

I think absolutely and I think that's something that, you know, maybe people don't realise about writing, because, you know, there's a great many people for whom, you know, they're just readers writing themselves, you know, they wouldn't have an interest in and I think any piece of writing even the most basic sentence, actually is the product of a lot of work. Sometimes that work happens from speaking to other authors. Sometimes that work happens kind of intuitively, it's kind of going on, you know, in the brain somewhere and then sometimes it's very conscious because you can come across, you know, a sentence that just, you need it to happen and you need it to get to a certain point that actually getting it there is...

Julia Boyd 50:45

Oh, you're so right, you absolutely put your finger on it. But I mean, I must admit, I really enjoy the process of writing, people often ask, you know, whether I prefer to do the research or the writing. But for me, they're absolutely dovetailed. I mean, until I've done some research, I've got no material to write about. But equally, I can't really make sense of the research until I start trying to put it down on paper. So I find doing the two together is, for me, the most satisfying way of approaching a project.

Jack Wrighton 51:17

Yes and again, I imagine with that you end up with something that's sort of bigger than the final...

Julia Boyd 51:22

Oh, yes. I can't do proposals for publishers at all, because absolutely no idea where I'm headed and mostly, I don't usually know an awful lot about the subject until I start writing about it. But then once you're in, you know, every tiny little scrap of information becomes important and that's another problem, particularly perhaps, with this kind of writing is, you know, if you've spent all day in a slightly chilly archives, but you've only got one bit of information out of it, you're either keen to use it even if it's not that important. So one has to be rigorous and very disciplined when it comes to not using some favourite little nugget of information.

Jack Wrighton 52:07

I can imagine that maybe this is because, you know, I don't think I'd have the organisational abilities for this type of work. But I can imagine you're writing something and suddenly you think, Oh, actually, this would be a perfect place to put that snippet I read three weeks ago and then you're thinking, actually wait, where was that? Where did I put it?

Julia Boyd 52:30

Oh, tell me about it! I mean weeks and months I've spent since I started writing, hunting, and I can see where it was on the page but I can't find it. Ah, yes. I think anybody who writes probably I mean who writes history certainly suffers from that. Certainly I do.

Jack Wrighton 52:49

Well, yes they will understand that pain. Well, Julia, I think that's brought us to the end of our conversation. I want to thank you so much for joining us here at Mostly Books Meets. A Village in the Third Reich is out now currently in hardback and is available from Mostly Books, both in the store and online, but is also available from your own local bookshop as well wherever you're listening to this.

Julia Boyd 53:15

Jack it's been such a delight to talk to you. Thank you so much for inviting me.

Jack Wrighton 53:18

Oh it's been an absolute pleasure, Julia. Thank you so much.

Sarah Dennis 53:23

All of the books mentioned during the podcast are available to buy from the Mostly Books website. This podcast has been presented and produced by members of the team mostly books in Abingdon. If you enjoyed what you heard, please rate review and subscribe because apparently helps people find us.