Some of the most meaningful shifts in how we communicate come from the moments that challenge us the most. In this special 250th episode of Think Fast Talk Smart, Matt Abrahams reflects on the insights that have shown him how conflict can become a catalyst for clarity, connection, and even compassion.

From Amy Gallo’s reminder that the “right kind of conflict” leads to better outcomes to Jenn Wynn’s framework for calming our nervous system before stepping into a hard conversation and Julia Minson’s HEAR method for signaling genuine curiosity, each tool helps turn tension into understanding for every stage of conflict. And with Joseph Grenny’s guidance on noticing when our motives shift from problem-solving to winning, this episode highlights how self-awareness can reset even the toughest moments.

Whether you’re navigating workplace disagreements or everyday friction at home, this milestone episode offers practical ways to make difficult dialogue feel less daunting — and a real opportunity to communicate better.

Episode Reference Links:

- Amy Gallo

- Amy’s Book: Getting Along: How to Work With Anyone

- Ep.144 Communicating Through Conflict: How to Get Along with Anyone

- Jenn Wynn

- Jenn’s Podcast: The H.I. Note: Healing Inspirations from Life

- Ep.222 Discussing Through Discomfort: Why the Conversations You Avoid Cost You the Most

- Julia Minson

- Ep.136 The Art of Disagreeing Without Conflict: Navigating the Nuance

- Joseph Grenny

- Joseph’s Book: Crucial Conversations

- Ep.207 From Conflict to Connection: Having Crucial Conversations that Count

Music from Blue Dot Sessions:

- Premium Signup >>>> Think Fast Talk Smart Premium

- Email Questions & Feedback >>> hello@fastersmarter.io

- Episode Transcripts >>> Think Fast Talk Smart Website

- Newsletter Signup + English Language Learning >>> FasterSmarter.io

- Think Fast Talk Smart >>> LinkedIn, Instagram, YouTube

- Matt Abrahams >>> LinkedIn

Timed Links:

Chapters:

- (00:00) - Introduction

- (03:15) - Why Conflict Is Necessary

- (04:14) - Transforming Unproductive Conflict

- (05:02) - Inner Experience of Difficult Conversations

- (05:58) - Self-Awareness, Pause, Reframe

- (08:05) - Four Questions For Understanding

- (11:24) - Acting Curious vs. Feeling Curious

- (13:40) - The HEAR Framework

- (18:02) - Humility & Willingness To Be Wrong

- (19:33) - Practice & Repetition

- (21:00) - Acknowledging Motives

- (22:14) - Two Questions to Reset Motives

- (24:08) - Bringing the Frameworks Together

- (25:34) - What Really Matters

- (27:06) - Conclusion

Thank you to our sponsors. These partnerships support the ongoing production of the podcast, allowing us to bring it to you at no cost.

Visit virtualspeech.com to learn how AI-powered learning can transform your team

Join our Think Fast Talk Smart Learning Community and become the communicator you want to be.

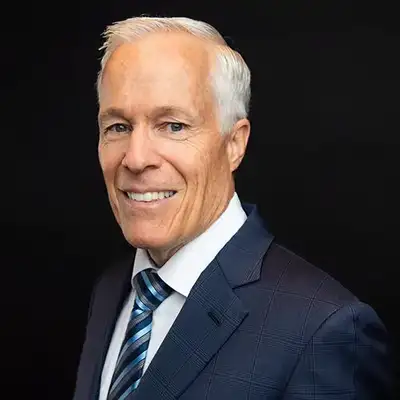

Creators and Guests

What is Think Fast Talk Smart: Communication Techniques?

One of the most essential ingredients to success in business and life is effective communication.

Join Matt Abrahams, best-selling author and Strategic Communication lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business, as he interviews experts to provide actionable insights that help you communicate with clarity, confidence, and impact. From handling impromptu questions to crafting compelling messages, Matt explores practical strategies for real-world communication challenges.

Whether you’re navigating a high-stakes presentation, perfecting your email tone, or speaking off the cuff, Think Fast, Talk Smart equips you with the tools, techniques, and best practices to express yourself effectively in any situation. Enhance your communication skills to elevate your career and build stronger professional relationships.

Tune in every Tuesday for new episodes. Subscribe now to unlock your potential as a thoughtful, impactful communicator. Learn more and sign up for our eNewsletter at fastersmarter.io.

Matt Abrahams: The biggest fight my wife

and I have ever had was over toothpaste.

Picture this, my wife and I

are newly married and excited

to start our life together.

We spent a lot of time discussing

and coming to agreement on the

big things, having children in

the future, our political ideas,

where to spend the holidays.

So imagine my surprise when I was summoned

to the bathroom where my wife was angrily

holding our shared tube of toothpaste.

Her gaze immediately told me that

this was serious and I was in trouble.

You see, my wife's a roller and I'm a

squeezer, and nothing is more irritating

to a fastidious roller than a smashed

up randomly squeezed tube of toothpaste.

Welcome to Think Fast

Talk Smart, the podcast.

I'm Matt Abrahams, and I teach

strategic communication at Stanford

Graduate School of Business.

Today is a special day.

It's our 250th episode.

We've put together a very special

episode just for you, and it's

going to sound a little different.

You'll hear a few more voices, a

little more storytelling than usual,

plus some music and sound design too.

We're celebrating by digging into

the Think Fast Talk Smart archives.

We've compiled some of the best

expert advice on one of the hardest

things we face in life: conflict.

We face it at work, at home, and sometimes

even with friends and complete strangers.

It seems like the closer we get to

someone, the more conflict we face.

But here's the really

interesting thing about conflict.

Conflict isn't bad.

In fact, we need it.

Amy Gallo: While our natural human

instinct is to avoid conflict because

of course we are hardwired for

likability and we see conflict as a

potential rupture in our relationship.

Conflicts are not only inevitable

part of interacting with other

humans, but they're a necessary part.

Matt Abrahams: That was Amy Gallo.

She's the author of Getting Along: How to

Work with Anyone, Even Difficult People.

She also wrote the Harvard Business

Reviews Guide to Dealing With

Conflict and has been the co-host

of HBR's Women at Work Podcast.

Amy Gallo: There's lots of research that

shows that conflict leads to better work

outcomes, stronger relationships, and of

course, that depends on navigating the

conflict in a professional, productive,

relational way with compassion and caring.

But when done well, conflict has a whole

host of good outcomes, and I think we

actually should be spending more time, not

trying to eliminate conflict, but trying

to create the right kinds of conflict.

Matt Abrahams: So what are the right

kinds of conflict and how do we move

away from conflict that's destructive

to our relationships and toward

conflict that will make us closer.

Amy Gallo: The idea is not to eliminate

conflict, even if we feel like it's

unhealthy, but it's to try to transform

it into something more productive.

'Cause usually even at the base

of those unhealthy conflicts or

those unproductive conflicts is

something that needs to be resolved.

Matt Abrahams: Transforming, conflict

into a productive resolution.

Where can I get more of that?

We've talked a lot about difficult

conversations on Think Fast Talk Smart.

What was interesting as we went

through our past episodes to find the

best tips on dealing with conflict

is that they all had a common theme.

Resolving conflict is much less about

the other person and much more about us.

Jenn Wynn: What makes a conversation

difficult is much less the topic

and much more the inner experience

that each person is having.

What you're thinking and

feeling, but not saying out loud.

Matt Abrahams: That was Jenn

Wynn, an award-winning professor

and the former Director of

Education at the Obama Foundation.

Jen also hosts the podcast, The

H.I. Note: Healing Inspirations from

Life, where she has conversations

with people about some of the most

difficult moments of their lives.

Jenn Wynn: Your nervous system

goes with you into every

single difficult conversation.

So if you can pause and regulate

your nervous system, then you're

gonna be a better version of yourself

at the time when you most need to

be the best version of yourself.

And at the end of the day, the

goal is to move away from emotional

reactivity towards choice.

I wanna choose the better, more

strategic path, not the reaction that

came out of an emotional trigger.

Matt Abrahams: Sometimes I find

myself thinking about healthy

conflict as a house I'm building.

I tell myself, if I can just lay the

right foundation and choose the right

materials, I'll be set for life.

But conflict is less like building a

house and more like pitching a tent.

The more we use it, the easier it is to

remember exactly how we put it together.

The weather, or how level the ground is,

or how many rocks or trees we're working

around, all affect how successful we'll be

at securing a safe, comfortable campsite.

Just like surveying the ground and weather

is the first step for setting up our

campsite, tuning into how we're feeling

is the foundation for a healthy conflict.

Jenn Wynn: I tell my students, if

you only remember one framework from

this entire course, please remember

self-awareness, pause, reframe.

Matt Abrahams: Self-awareness,

pause, reframe.

Let's break that down.

First, self-awareness.

Jenn Wynn: Am I aware of my physical

cues, my cognitive and emotional

cues that let me know I'm triggered?

So for me, I get a lump in my throat

or like a tightness in my chest.

Some people get, uh,

butterflies in their stomach.

What's my tell sign, right?

And once I know that, the moment

I see it, I know I've gotta pause.

So a go-to pause technique for me is to

imagine myself with my best friend Carla.

Then I'm at ease.

I'm centered, and that is our goal,

that we lead these conversations

to a productive outcome, both

for the content, the matter at

hand, and for the relationship.

Matt Abrahams: Once we've had a chance

to survey the situation and notice

how we feel, and then pause and calm

down our nervous system, the final

step in this framework is to reframe.

Jenn Wynn: So that last step, reframe,

is where I actually shift away from

viewing this conversation as a threat

to something I care about and instead

perceiving it as a learning opportunity.

What good information

can I get out of this?

Matt Abrahams: Reframing the

conversation so that we can see it

as a learning opportunity makes a

huge difference in how we show up.

This is something Amy talked about too.

Amy Gallo: Conflict is

often seen as a threat.

When that happens, we become

naturally narcissistic and we become

focused on, what do I wanna say?

What do I wanna do?

We don't think about the other person.

Matt Abrahams: Thinking back to the

toothpaste conflict, it might have helped

me if I'd taken a moment to follow Jenn's

framework, self-awareness, pause, reframe.

Just that quick check-in probably

would've changed my stance going into

this challenging conversation and

made me more curious about how this

conflict might be a good opportunity

to get to know my wife better.

And it turns out curiosity is key

to any difficult conversation.

Amy Gallo: The very first step

is to think strategically, what's

going on with that other person?

What's motivating them?

What do they care about?

What would be a rational reason

that they're behaving this way?

And that's gonna give you some

cues as to how to navigate

this not so healthy conflict.

Put yourself in their shoes

just for a few minutes.

Matt Abrahams: What is it that my wife

really cares about when she asks me to

roll the toothpaste tube from the bottom

instead of squishing it like Play-Doh?

Maybe she's more motivated by

order and consistency than I am.

Maybe she's constantly having

to overlook annoying behaviors

from her colleagues at work.

And having one more irritation

at home in her safe space

just puts her over the edge.

Even if I'm wrong about my guesses,

just imagining where she's coming

from makes me more compassionate.

Amy Gallo: Then you wanna think about

what are we actually disagreeing about?

Are we disagreeing about status?

Who actually gets to make the call?

Really try to understand.

Matt Abrahams: For me, squeezing the

toothpaste tube isn't a big deal.

In fact, it makes me feel

powerful and it's fun.

But for her, it was a sign that

I wasn't really listening to her,

which made her feel disrespected.

The argument really wasn't

about toothpaste at all.

It was about listening and

communicating my respect for her.

Amy Gallo: Then the third step

is to think about your goal.

What is it that I

actually want to achieve?

You might be tempted to have a

short-term goal, like I just wanna

prove I'm right and he's wrong.

Not helpful, right?

What's your long-term goal?

What is it that you need to

get this project done on time?

Is it that you wanna preserve your

relationship with the other person?

Whatever it is, focus on that.

Matt Abrahams: When my wife called me

into the bathroom, I got defensive.

I started trying to prove what a

great husband I was, but focusing on

the short-term goal of winning that

argument made both of us losers.

A better goal, the real goal, once I

stopped to think about it, was to live

in harmony with my new wife and make

sure she knew how much I loved her.

I married her because she's my

favorite person in the world.

She makes me better.

When I think about it like that,

it seems ridiculous to let a tube

of toothpaste come between us.

Amy Gallo: And with that information,

what you know about the other person,

what you know you're disagreeing

about, what your goal is, you then

make a decision about how to proceed.

We often act rashly because we're

sort of activated from the conflict,

but you have to really be thoughtful.

Does it make sense to sit

down and talk this through?

Who else might need to be in the room?

Should I have a phone call?

Should I do a Zoom meeting?

Whatever it is, think through

what's the best way to set up

this conversation for success.

Matt Abrahams: There's one more

element we need to consider when we're

preparing for hard conversations,

one that we might not even be able

to see even after going through

Jenn's framework and Amy's questions.

Julia Minson: There's a lot of advice out

there, both in the academic literature

and in the practitioner literature,

that says to navigate disagreement

better, you need to be curious about

the other person's point of view.

Matt Abrahams: That's Julia Minson,

a professor of Public Policy at

Harvard Kennedy School of Government,

and a decision scientist who studies

the psychology of disagreement.

Julia Minson: The problem is people

think they're already doing it.

Matt Abrahams: We often think we're

being curious, but we don't show it.

Julia Minson: So a lot of the work

we've been doing as a consequence of

that research is saying, let's stop

telling people to feel curious and let's

start telling people to act curious.

Matt Abrahams: Julia told me

about a fascinating study where

participants had to start and end

their arguments with the words, I'd

like to learn about your perspective.

Julia Minson: We ask participants in a

study to make an argument on a topic,

and then we ask them to write a paragraph

about what their point of view is.

We then take that paragraph and

then we stick two sentences on the

beginning and two sentences on the end.

And the sentences say something

like, I understand this is a really

complicated topic and I would love

to understand your point of view.

And then their own paragraph

comes after that, right?

I believe blah, blah, blah, blah,

blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

And at the end we say, but I get that

some people might disagree and I would

like to learn about your perspective.

So we didn't change anything

about the person's argument.

We just slapped two sentences on

the beginning, on the end that use

very simple language to say, I want

to learn about your perspective.

And what we find is massive effects

on how reasonable and thoughtful

and pleasant the original speaker is

relative to their own words, which was

the same exact argument, just without

this expression of willingness to

learn, on the beginning and on the end.

Matt Abrahams: In other words, just

saying the words, I'd like to learn about

your perspective, makes a difference.

But what about the part in

between where we actually need

to have that hard conversation?

Julia Minson: We use a

framework that we call HEAR.

So H-E-A-R.

Hedging, emphasizing agreement,

acknowledging the opposing view,

and reframing to the positive.

The H in HEAR stands for hedging, so it's

words like sometimes, occasionally, some

people, words that introduce uncertainty.

Matt Abrahams: With the toothpaste

incident, I might have hedged by saying

something like, sometimes I forget

how important order is to you, and I'm

guessing there have been many times when

you've forgiven me for my messiness.

Julia Minson: The E stands for emphasizing

agreement, and the idea here is that

even if we disagree dramatically

about the thing we're discussing,

there are some things we agree on.

Matt Abrahams: I might have said

something like, I know it's important

for both of us that our house feels

like a place where we can rest and feel

at home, and that neither of us wants

to nag each other over little things.

Julia Minson: The A for acknowledgement

is using your own words to show that

you have heard the other person.

And I like to make a little bit

of a disclaimer around the A,

because there's a good way to do

it and there's a bad way to do it.

The bad way is to say, I hear you, and

then you move on to making your own point.

The good way is that you have

to demonstrate what you heard.

Matt Abrahams: It's easy to say, I

hear you when you ask me to roll the

toothpaste instead of squeeze it.

But demonstrating I heard my wife's

request requires me to get deeper,

to what's really bothering her.

What I finally came up with was

this, when you asked me to roll

the toothpaste, I hear you asking

me to do something small that will

make you feel heard and respected.

Julia Minson: And then the R in HEAR

stands for reframing to the positive.

So instead of saying, I completely

disagree that blah, blah, blah, you

could say, I think blah, blah, blah.

You can make the same exact point

in the positive frame instead of

the negative frame, so it doesn't

spiral into negativity as quickly.

So H-E-A-R.

Hedging, emphasizing agreement,

acknowledging the opposing view,

and reframing to the positive.

Matt Abrahams: So we've got

Jenn's framework to help us check

in with ourselves once we're

aware that conflict is coming.

Self-assessment, pause, and reframe.

Amy's four questions help us to

shift the focus off of us and get

curious about the other person.

One, what's a rational reason this

person might be acting this way?

Two, what are we really disagreeing about?

Three, what's the goal

of this conversation?

Four, what's the best way to proceed?

Then we can use Julia's HEAR framework to

help us actually have the conversation.

Thinking about these three tools

together makes me wanna shift metaphors.

It's got me thinking about conflict,

not as a tent, but as a stone.

When you drop a pebble in the

water, waves ripple out in circles.

The first circle is

checking in with ourselves.

The next ripple out is thinking

about the other person and

where they're coming from.

Then we can use HEAR to navigate the

third ripple, the actual conversation.

There's another ripple that came

out in our conversation and it's

one that might surprise you.

Julia Minson: The willingness to

come across as little foolish.

Jenn Wynn: A real humble attempt to

say, this is my summary of what I think

you experienced, but is that right?

Fix what I'm missing.

Is it half right?

And I missed the other half.

Matt Abrahams: Paraphrasing what

we think we heard the other person

say, and having the humility to

admit we might have gotten it wrong.

Julia Minson: You know, showing

vulnerability or saying, I'm sorry,

that's not what I meant to say.

Let me try again.

Amy Gallo: Saying I don't know what

the best answer is, and this is

why I'm doing what I'm doing, and

I'm a real person who's struggling.

Julia Minson: Giving yourself

the chance to admit imperfection,

so you can do better.

Jenn Wynn: Once we can paraphrase,

this is a skill that, honestly, I think

it's like punching above its weight.

After I've taken all this time to really

ask these open, thoughtful questions,

get curious, understand your perspective,

make sure you show the person that

you are internalizing what they said.

Matt Abrahams: Thinking back to the

toothpaste incident again, I could have

said something like, I really wanna

understand where you're coming from.

It seems like I'm not doing a good

enough job showing you that I'm listening

to you and making you feel respected.

Is that right?

Or is there something I'm

still not understanding?

I really want to understand your

perspective because the last thing I

want to do is to have you feel like

I'm not listening or respecting you.

We might be tempted at this point to

rush into a difficult conversation

now that we've done all of our great

self-reflection, and thought through

our goals and how to achieve them.

But there's one last ripple,

a step we often skip that

can make all the difference.

Jenn Wynn: Practice.

At the end of the day, the

goal is not perfection.

It doesn't exist.

The goal is continual improvement.

I wanna keep getting better and better.

And so the way to do that, of course, like

any muscle building activity is practice.

And as we continue to have more and

more repetition, right, as we build

in the reps, we're not only gonna

build the muscle, which feels good.

But then it's gonna be ready for

us to flex when the moment counts.

When we're in the most consequential

conversation, we will have already

built up those great question asking

muscles, those great paraphrasing

muscles, those great intention stating

muscles and so on and so forth.

So, practice, practice, practice,

and make it a little more

challenging each time along the way.

Matt Abrahams: Listening back to these

conversations with Amy, Jenn, and

Julia, I'm struck by how much focus

there is on what happens before the

difficult conversation even starts.

But what if we do all that and then we

get into the actual conversation and

it doesn't go the way we were hoping?

Joseph Grenny: What's difficult in

crucial conversations is oftentimes our

motives shift to debating or defending

without us even being aware of it.

Matt Abrahams: That's Joseph Grenny, a

renowned speaker and bestselling author.

His work focuses on how individuals and

organizations can improve communication,

influence, behavior, and drive change.

Joseph Grenny: People will tell

you, you're being defensive.

No, I'm not being defensive.

It looks like to them

you're being defensive.

I came in with a motive of

problem solving, but pretty

soon I got ego invested and

oftentimes we're not self-aware

that that has actually occurred.

Matt Abrahams: This one hit home for me.

In my conversation with my wife, I was

already feeling criticized and defensive,

and then my ego took over because I

wanted to prove that squeezing toothpaste

didn't make me lazy or inconsiderate.

But there's good news here.

If we can notice that our motives

have shifted and we just want

to win the argument, we have an

opportunity to shift the conversation.

Joseph Grenny: People who are

really good at these moments

learned to look for signals.

Sometimes it's just

something I feel in my body.

I've come to know that when my jaws

are tight and when my shoulders are

clenched and I'm leaning forward

and I'm talking faster, that's

a sign my motives have shifted.

I no longer want what I originally wanted.

I now want something else.

I wanna punish, I want to

win, I want to be right.

The two most potent ways of

shifting back, of getting to

dialogue, are asking two questions.

First, what am I acting like I want.

You can do this covertly.

This can be an internal dialogue.

And I gotta tell you, Matt, at

least for me, it's an ego enema.

When in that moment I acknowledge to

myself, no, this is about punishing.

You said something I didn't like,

I'm feeling hurt, and that that

was unjust, and I'm actually

trying to hurt you right now.

Just acknowledging that to myself

makes me not want it anymore.

Because most of us don't like the

dissonance of thinking of ourselves

as a decent human being, but then

acknowledging that we've got motives

that are not particularly pretty.

Matt Abrahams: Once we've asked ourselves

what we're acting like we want, the second

question is to ask, what do I really want?

Joseph Grenny: What do

I really want for me?

What do I really want for you, Matt?

What do I really want

for the relationship?

What happens is the short term impulsive

motives that often possess us in these

moments, we start to be liberated of

those and asking the really want question

orients us towards longer term goals,

some of the deeper interests that we have.

Just acknowledging that

to myself shifts my mode.

My behavior starts to change.

When your motive changes

behavior follows naturally.

And we tend to talk more patiently, more

respectfully, more openly towards others.

So even without a lot of training in

crucial conversation skills, just getting

your motive back on track can make an

enormous difference in how you show up.

Matt Abrahams: Let's bring it

all together one last time.

First, use self-awareness, pause,

reframe to check in with ourselves.

If the conflict is the pebble we

throw in the water, checking in

with ourselves is the first ripple.

The next ripple is to get curious

about the other person and

ask ourselves four questions.

What's a rational reason this

person might be acting this way?

What are we really disagreeing about?

What's the goal of this conversation?

And what's the best way to proceed?

The third ripple is to practice the

conversation by using HEAR, H-E-A-R.

Hedging, emphasizing agreement,

acknowledgement, and reframing

towards the positive.

If you don't have someone to practice

with, try recording your conversation

in a voice memo on your phone.

You can even feed it into your favorite

AI tool to anticipate how the other

person might respond, and then practice

using the tools in this episode to

paraphrase what they've said and make

sure they feel heard and understood.

Finally, if we're in a difficult

conversation and it's not going well, stop

to notice how we're feeling in our bodies.

Then ask, what am I acting like I want?

Revenge?

Making the other person feel bad?

Once we've gotten that ego enema,

we're in a much better place

to ask, what do I really want?

And remind ourselves of the importance of

the relationship and what really matters.

Jenn Wynn: Often when we don't

have the conversation, it's because

we assume it will go poorly.

So we give up before we've even started.

But here's the thing.

Most things that we want in

life are on the other side

of a difficult conversation.

So are you just going to give up on your

biggest dreams in life because you weren't

willing to take the time to step outta

your comfort zone and practice a skill?

Communication is a set of skills,

learnable, growable skills.

And difficult communication is a

set of hard, but worth it, skills.

Joseph Grenny: The world will get better

to the degree we start seeing more

examples of people that have learned

to say the truth and to say it in a

way that is inclusive and is inviting.

You don't just get

better at it by accident.

And the really important thing for

people to understand during crucial

conversations is the emotion you feel

is far more subject to your control

and influence than you realize.

Matt Abrahams: Eventually, my wife and

I did have that difficult conversation,

not just about toothpaste, but about how

I could communicate more clearly with

her that I respect her and show her I'm

listening when she asks for something.

To this day, we have two tubes

of toothpaste in our bathroom.

One neatly rolled in, one

aggressively squeezed.

As an epilogue, there was a time

when my younger son got upset with my

wife and having heard this story many

times about our toothpaste troubles,

he ran into the bathroom and squeezed

her toothpaste just to make a point.

Thank you for joining us for

this 250th episode of Think

Fast Talk Smart, the podcast.

To hear more episodes about

conflict and navigating difficult

conversations, check out our show notes.

This episode was produced by

Laura Joyce Davis, Katherine

Reed, and me, Matt Abrahams.

Our theme music is from Floyd Wonder.

Additional music from this episode

came from Blue Dot Sessions and

is listed in our show notes.

With special thanks to

Podium Podcast Company.

Please find us on YouTube and

wherever you get your podcasts.

Be sure to subscribe and rate us.

Also follow us on LinkedIn,

TikTok, and Instagram.

And check out fastersmarter.io for

deep dive videos, English language

learning content, and our newsletter.

Please consider our Think Fast Talk

Smart Learning Community, where you

can join a global community of people

interested in honing and developing

their communication and career skills.

You get access to asynchronous

lessons, an AI coach, quests

and challenges, and much more.

Join us at fastersmarter.io/learning.

That is fastersmarter.io/learning.